in this issue

general news

Welcome to the April issue of Ancient News!

Through the end of the month, save 40–50% on select titles in Babylonian Studies when you use promo code BBLYS at checkout. Browse the titles on sale here! Sale ends 4/28.

In this issue, we are featuring a Q&A with María Victoria Almansa-Villatoro and Silvia Štubňová Nigrelli, editors of Ancient Egyptian and Afroasiatic: Rethinking the Origins. Read on or visit our Tumblr for the full conversation.

In case you missed it, the Penn State University Press Spring/Summer 2024 catalog is now available! Browse the catalog for a sneak peek at the exciting new titles coming later this spring for Eisenbrauns!

Enjoy!

Maria Metzler, Acquisitions Editor

babylonian studies sale

Save 40%–50% on select titles with promo code BBLYS. Sale ends 4/28.

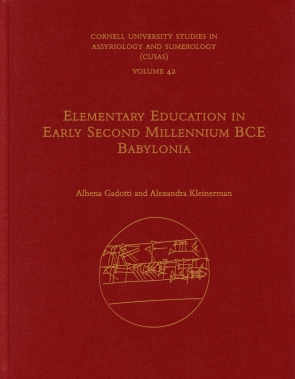

Elementary Education in Early Second Millennium BCE Babylonia

$89.95 $53.48

In this volume, Alhena Gadotti and Alexandra Kleinerman investigate how Akkadian speakers learned Sumerian during the Old Babylonian period in areas outside major cities.

As Above, So Below

Religion and Geography

$109.95 $65.97

This volume addresses the nexus of religion and geography in the ancient Near East through case studies of various time periods and regions.

Fault, Responsibility, and Administrative Law in Late Babylonian Legal Texts

$106.95 $53.48

“An important building block for a better understanding of the social conditions in Babylonia in the 6th and 5th centuries B.C. and at the same time enriches the corresponding legal-historical research.”

Babylonia, the Gulf Region, and the Indus

Archaeological and Textual Evidence for Contact in the Third and Early Second Millennia B.C.

$63.95 $38.37

During the third millennium BC, the huge geographical area stretching between the Mediterranean in the west and the Indus Valley in the east witnessed the rise of a commercial network of unmatched proportions and intensity, within which the Persian Gulf for long periods functioned as a central node. In this book, Laursen and Steinkeller examine the nature of cultural and commercial contacts between Babylonia, the Gulf region, and Indus Civilization.

new books

The Queens of the Arabs During the Neo-Assyrian Period

Ellie Bennett

In press!

The title “Queen of the Arabs” is applied in Neo-Assyrian texts to five women from the Arabian Peninsula. These women led armies, offered tribute, and held religious roles in their communities from 738 to approximately 651 BCE. This book discusses what the title meant to the women who carried it and to the Assyrians who wrote about them.

The Southern Wall of the Temple Mount and Its Corners

Past, Present and Future

Edited by Yuval Baruch, Ronny Reich, Moran Hagbi, and Joe Uziel

“The Temple Mount/Haram aš-Šarīf has fascinated scholars since the dawn of modern archaeology, and the pious for millennia before that. The studies assembled here document excavations and conservation at the southern and southwestern retaining walls of the Herodian Temple, with special care for all periods—from the Iron Age to Herod the Great to medieval Islam. This magnificent volume is a monument to decades of dedicated research, a resource for generations to come!”

Before There Were Kings

A Literary Analysis of the Book of Judges

Elie Assis

“Assis utilizes a close reading of the book of Judges and interacts with the secondary literature while contributing to a reading of the text that explains how the parts produce the whole. Before There Were Kings makes an important contribution, not simply in the method of reading, but in the particular way in which Assis’s perspective contributes to an understanding of the book.”—K. Lawson Younger, Jr., Divinity School, Trinity International University

Assyrian-English-Assyrian Dictionary

Cuneiform Edition

Edited by Simo Parpola

This dictionary contains all the words attested in Assyrian texts from the Neo-Assyrian period. Most of the vocabulary comes from Neo-Assyrian and Standard Akkadian, with some Aramaic and Neo-Babylonian entries. The Assyrian-English-Assyrian Dictionary was the first English-Akkadian dictionary ever published, and the new cuneiform edition features words written in the cuneiform script of the Neo-Assyrian period.

author q&a

María Victoria Almansa-Villatoro and Silvia Štubňová Nigrelli, editors of Ancient Egyptian and Afroasiatic: Rethinking the Origins, joined us for a Q&A about their current research and how they hope it will shape the field.

Can you tell us about your current research, and how you became interested in the topic?

Almansa-Villatoro: I am mostly working on understanding how ancient Egyptians used language in specific social contexts, and how their choices to say things in certain ways, or omit information inform us about the way hierarchy, power, and ethics functioned. I study how Egyptians used politeness in personal letters, and what themes the king wants to emphasize in his royal discourse. What drew me to this topic is my conviction that we can learn so much about a specific culture by studying their use of language. As a scholar who has worked and lived in different countries, I am aware that when learning a new language, it is not enough to memorize rules and vocabulary, but one needs to know how to use indirectness, humor, or ambiguity in certain ways to convey specific things. And the way this is done is very variable across different cultures, but by looking at what is acceptable or unacceptable in certain contexts we can learn a lot about the underlying social and cultural values. I found for example that in Old Kingdom Egypt (c. 2600–2200 BCE) overt authoritarianism and coercion (even by the king) is frowned upon, and it is often camouflaged by indirect requests or euphemisms for acts of command. This teaches us that we can’t always take ancient texts literally and need to sometimes be able to read between the lines, but perhaps more importantly, that Egyptians considered impositions ethically reproachable.

Nigrelli: My research aims to elucidate the complexities of the ancient Egyptian grammatical system and to better understand the world and lived experiences of ancient Egyptians through linguistic and philological analyses of written sources. Most recently I have been working on refining our understanding of some medical terms associated with visual impairment. I became interested in the ancient Egyptian language already in high school, when I came across a crash course of hieroglyphs in a popular history magazine and knew immediately that that was something I had to study. I love reading the original texts as they open up the door to the world of the ancient Egyptians and show us that, in many respects, they were people like us. The medical aspect of my research comes from my husband, who is an eye doctor, so we tend to talk a lot about eye diseases and treatments, both modern and ancient.

How do you anticipate your research will inspire other research in your discipline?

Almansa-Villatoro: I have striven to raise awareness among my colleagues about the potential of applying the latest research methods in pragmatics and linguistics to the study of ancient sources, particularly (im-)politeness research and discourse analysis. These frameworks can bring us closer to the meaning of texts in their original ancient contexts, disentangled from what we, as modern scholars, think that the function of these documents should be. The use of interdisciplinary approaches not only shed new light on ancient data, but also enable a more nuanced understanding of the communicative or practical function of texts that we have imprecisely labelled as “propagandistic,” “religious,” or “literary.”

Nigrelli: I am hoping to show that our traditionally accepted translations of some words/phrases can be interpreted in a different way, leading to a new look at how the Egyptians perceived their world, and that we should devote more time to studying ancient Egyptian semantics and linguistics. It seems to me that nowadays the language plays a rather minor role in Egyptological curricula and research, which is unfortunate, because its knowledge is crucial for our understanding and interpretation of ancient Egyptian written materials and the world of ancient Egypt in general.

What are the advantages of examining ancient Egyptian in its African context?

Almansa-Villatoro: The complicated history of ancient Egyptian has been traditionally dominated by a semito-centric approach which Egyptologists are now generally rejecting. The relationships within the Afroasiatic family are still not well understood, and scholars (including the contributors of our volume) do not even agree on what languages to include in the phylum. Ancient Egyptian in particular has the added difficulty of being attested for several millennia without a close relative. The other Afroasiatic languages that co-existed with Egyptian for much of its history were Semitic (e.g. Akkadian), and this contemporaneousness may have resulted in a bigger number of perceived similarities. In contrast, other African languages do not appear in the written record until much later, when Egyptian had gone through millennia of development. However, it is undeniable that most of the Afroasiatic languages are nowadays located in Africa, and Egyptian probably interacted with them for many centuries before the earliest texts. This is why we wanted to invite the contributors of our volume to rethink the origins of Afroasiatic and try and reconstruct the history of ancient Egyptian through its similarities to other languages in the phylum from the point of view of phonology, lexicon, and syntax. The surprise was that, depending on what aspect of the language one chooses to focus on, the resulting trees and genetic links are completely different. Hopefully these results will pave the way for future research on ancient Egyptian and Afroasiatic.

Nigrelli: Looking at the ancient Egyptian language within its Afroasiatic context is important for our understanding and classification of the languages in this family and it should also help us with studying the interrelations among the early cultures, i.e., the speakers of the Afroasiatic languages. Trying to figure out the proto-language of each member of this language family should be the first step in reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic. However, since ancient Egyptian constitutes a single branch in the Afroasiatic language family, we can’t compare it to other languages when trying to reconstruct Pre-Egyptian. We can work on its internal reconstruction to some extent, but that’s very difficult. That’s also why we organized this workshop—to explore, despite all these drawbacks, whether there is any methodological framework that could be employed to determine a more precise relationship among the Afroasiatic languages.

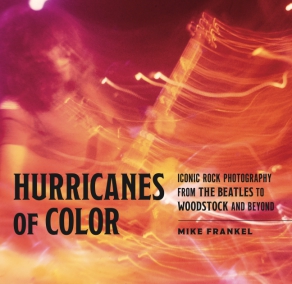

new from psu press

VIEW PSU Press News, the PSU Press newsletter| Control your subscription options |