in this issue

general news

Welcome to the July issue of Ancient News!

Eisenbrauns will be in-person at RAI in Leiden next week! Stop by our booth to browse books and pitch your projects to editor Maria Metzler.

We’re currently running a sale on all volumes in the Cornell University Studies in Assyriology Series (CUSAS). Use code SAS23 at checkout to receive 40% off and free domestic shipping on orders of $100 or more. Sale ends 7/23.

In case you missed it, the Penn State University Press Fall/Winter 2023 catalog, featuring a section of forthcoming titles from Eisenbrauns, is now live! View the catalog here to see what we’re publishing later this year.Enjoy!

cusas sale

Use discount code SAS23 at checkout. Sale ends 7/23.

Elementary Education in Early Second Millennium BCE Babylonia

$89.95 $53.97

In this volume, Alhena Gadotti and Alexandra Kleinerman investigate how Akkadian speakers learned Sumerian during the Old Babylonian period in areas outside major cities.

CUSAS 01

The Cornell University Archaic Tablets

$101.95 $61.17

Includes 220 archaic tablets (with photograph, seal impression, copy, transliteration, and commentary) and an 86-page glossary of all terms with their context lines in the texts.

CUSAS 36

Old Babylonian Texts in the Sch°yen Collection Part One: Selected Letters

$106.95 $64.17

This volume presents a selection of 216 Old Babylonian letters as a first installment of the Sch°yen Collection’s holdings of these documents. To these have been added five letters now in another private collection, making 221 in total. The letters are edited in transliteration and translation; the cuneiform is presented mostly in the form of photographs.

Ur III Texts in the Sch°yen Collection

$160.95 $96.57

Judging from the sheer amount of textual material left to us, the rulers of ancient Ur were above all else concerned with keeping track of their poorest subjects, who made up the majority of the population under their jurisdiction. The texts published in this volume—dating from the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2100–2000 BC)—attest to the immense investment of the ancient rulers in managing their subjects.

new books

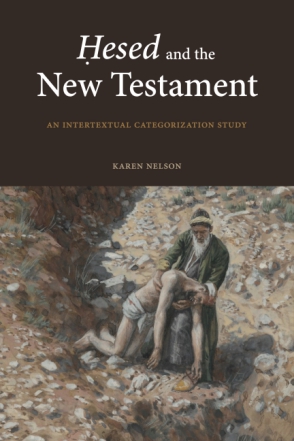

Ḥesed and the New Testament

An Intertextual Categorization Study

Karen Nelson

Ḥesed (steadfast love, loyalty, devotion) denotes an important concept in the Hebrew Bible that is relevant to interpersonal relationships in every generation. In this book, Karen Nelson investigates New Testament approaches to that concept and the exegetical value of recognizing such engagement.

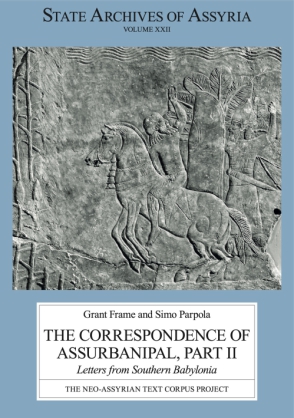

The Correspondence of Assurbanipal, Part II

Letters from Southern Babylonia

Edited by Grant Frame and Simo Parpola

The present volume completes the critical edition of the political correspondence of Assurbanipal, the first part of which was published in SAA 21. The 163 letters edited here were sent from southern Mesopotamia and Elam, mostly by governors or other high-ranking local administrators and military commanders.

An Annotated Sumerian Dictionary

Mark E. Cohen

Sumerian was the first language to be put into writing (ca. 3200–3100 BCE), and it is the language for which the cuneiform script was originally developed. Even after it was supplanted by Akkadian as the primary spoken language in ancient Mesopotamia, Sumerian continued to be used as a scholarly written language until the end of the first millennium BCE. This volume presents the first comprehensive English-language scholarly lexicon of Sumerian.

Aramaic Loanwords in Neo-Assyrian 911–612 B.C.

Zack Cherry

In press!

This study identifies and analyzes Aramaic loanwords occurring in Neo-Assyrian texts between 911 and 612 B.C. As two Semitic languages, Neo-Assyrian and Aramaic are sibling-descendants of a postulated common ancestor, Proto-Semitic. The work provides information about the contact between the two languages and about the people who spoke them.

author q&a

John R. Spencer and Jeffrey Blakely, two of the editors of Hesi after 50 Years and 130 Years, joined us for a Q&A to discuss the current field of archaeology and how technology has helped their research.

Can you tell us about your current research, and how you became interested in the topic?

Spencer: I came to archaeology from biblical studies. I was trained with, and adhere to, the idea that the cultural, historical, and physical context helps to illuminate the writers and writings of the biblical text. Thus, courses in ancient near eastern history, religion, and archaeology were essential for pursuing my Ph.D. in biblical studies. Indeed my first contact with archaeological finds was handling material that was then called “Samaria Ware.” Unfortunately, I was not immediately able to follow the study with field work. Once I started working on sites in Israel / Palestine I clearly understood, first hand, the importance of the principles I had learned in graduate studies.

Blakely: The Joint Expedition began in 1970 and I first came the following year, after my first year in college. I was taken by the discipline, eventually committing to it. My research interests focus on the Greater Hesi Region through time, unlike most in the field who specialize in single periods over an expansive region. I believe this alternate approach is beneficial in understanding many aspects of a multiperiod site like Tell el-Hesi. The two approaches can sync quite well in collaborative research.

How has technology affected your research over time?

Spencer: My introduction to field work was at Hesi, which employed the best holistic methodology available at that time. Hesi saw the importance of using experts from balk carvers, to osteologists, to botanists to geologists. And the staff stresses the importance of thorough recording of data and “clean” digging methodology. The field of archaeology has certainly continued to expand and improve, but the techniques of preserving materials from Hesi has made volumes like this one possible.

Blakely: Technological advances have opened up so many new avenues to research, and this is wonderful. The discipline and science are developing in new ways. Honestly, however, it is also a curse for folks trying to publish what are now termed “old excavations” like Hesi. You keep trying to retrofit the old data and ask new questions, but by the time you get a new understanding of the old data, technology has moved on and you again find yourself behind the times. Then, of course, much of the new technology is rather expensive and funding new analytical approaches to “old excavations” is challenging.

How do you anticipate your research will help inspire other research in the field?

Spencer: The study of the large collection of Early Bronze Age terracotta animal figurines has provided an opportunity to explore their presence at Hesi, and to catalog their presence elsewhere in the ANE. More important, it has allowed entry into the ongoing discussion of the function of these figurines. Are they toys? Are they cultic or “magical” objects? Or have they been used in both manners? While the answer is not clear, the Hesi materials makes it difficult to see them simply as cultic artifacts. It is now the turn of others to add to the catalog of animal figurines and to participate in the discussion of their function.

Blakely: I am not sure I would use the word “inspire.” I might use the word “challenge.” My mentor, Larry Toombs, always taught to go from the known to the unknown and to follow where your research dictates, even if it gets uncomfortable. Some of our results do not fit the generally accepted historical narrative for the discipline. I hope others investigate how our results might challenge their assumptions. Interestingly, Toombs was more worried when one’s results perfectly matched expectations. In such cases he demanded you then question your basic assumptions and methods. In my entire career I cannot think of a single time when the final results of our research were what we expected when we started. Depending on your point of view, that statement can yield rather different implications.

upcoming exhibits & events

Leiden, Netherlands

7/17–20

journals

new from psu press

Christian Interculture

Texts and Voices from Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds

Edited by Arun W. Jones

| Control your subscription options |