A City Transformed

Redevelopment, Race, and Suburbanization in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1940–1980

David Schuyler

A City Transformed

Redevelopment, Race, and Suburbanization in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1940–1980

David Schuyler

“In A City Transformed David Schuyler offers a body of new information on the effects of urban redevelopment on a small city. The Lancaster story is important in that it mirrors the frustrated efforts of so many other cities faced with the debilitating effects of economic decline. In the end we see how such cities fumbled the ball, sacrificing so much and getting so little in return.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

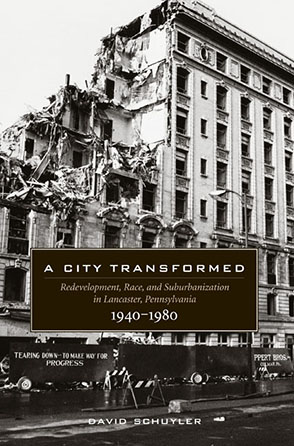

Beginning in the 1950s, the Lancaster Redevelopment Authority implemented a comprehensive revitalization program that changed the physical shape of the city. In attempting to solidify the retail functions of the traditional central business district, redevelopment dramatically altered key blocks of the downtown, replacing handsome turn-of-the-century Beaux Arts structures with modernist concrete boxes and a sterile public square. The strategy for eliminating density and blighted buildings resulted in the demolition of whole blocks of dwellings and, perhaps more importantly, destabilized Lancaster's African American community.

A City Transformed is a compelling examination of a northern city struggling with its history and the legacy of segregation. But the redevelopment projects undertaken by the city, however ambitious, could not overcome the suburban growth that continues to sprawl over the countryside or the patterns of residential segregation that define city and suburb. When the Redevelopment Authority ceased operating in 1980, its legacy was a city with a declining economy, high levels of poverty and joblessness, and an increasing concentration of racial and ethnic minorities—a city very much at risk. In important ways what happened in Lancaster was the product of federal policies and national trends. As Schuyler observes, Lancaster's experience is the nation's drama played on a local stage.

“In A City Transformed David Schuyler offers a body of new information on the effects of urban redevelopment on a small city. The Lancaster story is important in that it mirrors the frustrated efforts of so many other cities faced with the debilitating effects of economic decline. In the end we see how such cities fumbled the ball, sacrificing so much and getting so little in return.”

“Schuyler is intimately acquainted with the community, and the quality of his narrative rests upon his unrelenting scrutiny as to how Lancastrians wrangled over renewal and race. He is an omniscient observer, acutely aware of the nuances of local political culture and fluent in the argot of design, redevelopment, and the whims of architectural clients. . . . Amidst a raft of books on urban redevelopment, few are as shrewd and impassioned as this sad, familiar tale of a townscape lost.”

“This well-focused case study surveys how the political leadership of one city went about using, and fighting, various federal programs for replacing substandard housing, from the Depression to the suburban age.”

“A City Transformed provides a valuable complement to recent studies of comparable struggles over urban renewal in larger cities such as Minneapolis-St.Paul and Detroit.”

“A City Transformed would make an excellent reading in a course on planning history or urban studies. Policy makers would also benefit from reading the book.”

“But these comments should not gainsay respect for an admirable account about a city that struggled against colossal metropolitan trends. Amidst a raft of books on urban redevelopment, few are as shrewd and impassioned as this sad, familiar tale of a townscape lost.”

“David Schulyler’s history of urban renewal in the age of suburbia is a well-researched and well-told story of how American city governments often applied misguided strategies with disastrous results. Anyone who wishes to study the mutually reinforcing dynamics of suburbanization and urban decline should read this excellent study of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.”

“A City Transformed is an important, if depressing book. This study, carefully argued and closely researched through newspapers, planning reports, and government documents, tells a convincing story of the results of urban redevelopment in a small Mid-Atlantic city.”

David Schuyler is Professor of American Studies at Franklin & Marshall College. He is the author of Apostle of Taste: Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815-1852 (1996) and The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America (1986). He serves on the editorial board of the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers project and is chair of the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Board.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I: The Discovery of Urban Blight

1. The Postwar Housing Crisis

2. The Problem with Downtown

Part II: Planning a New Downtown

3. Best-Laid Plans

4. A New Heart for Lancaster

Part III: Race, Housing, and Renewal

5. Race and Residential Renewal: The Adams-Musser Towns Projects

6. Church-Musser: Race and the Limits of Housing Renewal

Part IV: Consequences

7. Sunnyside: The Persisting Failure of Planning and Renewal

8. Legacy: A Historic City in the Suburban Age

Notes

Index

Introduction

In 1980, the Redevelopment Authority of the City of Lancaster, Pennsylvania emblazoned across the cover of its final report, "This is the story of a city’s renewal. . . ." The narrative conceded failure as well as success, though its emphasis was on homes that had been given new life through renovation or restoration rather than buildings that had been demolished. Photographs captured the pride of individuals who were making improvements to their homes and families that were enjoying renovated domestic spaces, not the anguish of people who had been relocated when their dwellings were condemned and razed. What failures had occurred the report attributed to federal policies that mandated demolition rather than rehabilitation and that limited the range of options Lancaster’s leaders might consider. Despite this concession, the title and the photograph of a handsomely restored house on the cover emphasized the redevelopment authority’s accomplishments, celebrated the city’s renewal.

Nowhere was the impress of the redevelopment authority more apparent than in the contrast between streetscapes in the 1950s and those of the late 1970s, particularly in the southeast quadrant of the city, which had been home to Lancaster’s small minority population at the onset of renewal. In the 1950s, the report reminded readers, "some of our citizens still lived in tar paper shacks at the edge of town," others endured dwellings without running water and lived along unpaved streets. Twenty years later urban renewal had cleared blocks filled with dilapidated houses and removed junkyards and nuisance industries that once detracted from the quality of life. During the intervening years the city had constructed miles of curbs and sidewalks and a modern infrastructure of sewer, water, and utility lines, while new housing, a modern elementary school, a community center, recreational facilities, and open space replaced decaying old buildings. Two photographs published in the report harkened back to the years prior to renewal: one depicted a shack literally teetering on the brink of collapse, the other a group of men inspecting conditions along Dauphin Street. "We’ve come a long way since this tour was conducted," the report noted approvingly, and "eyesores" such as the frame dwelling had been removed.

The redevelopment authority’s final report also linked urban renewal and suburbanization, acknowledging that the "growth of suburbia spelled hard times for the economy of the downtown business sector." But if competition from a burgeoning suburban retail trade made the need for renewal of the central business district all the more pressing, the report did not mention the city’s principal commercial redevelopment project, which involved the demolition of almost the entire second block of North Queen Street. Perhaps because those events were so recent, the report’s authors did not feel the need to comment on the years of frustration the city’s leaders experienced in attracting a developer interested in erecting a new downtown commercial center, a decade when residents derisively described choice downtown real estate as "our hole in the ground." Perhaps the authority staff didn’t want to point to the most conspicuous failure of the redevelopment process, Lancaster Square, a retail and recreational space designed by the internationally famous architect and planner Victor Gruen, part of which was demolished only twenty-seven months after its dedication to make way for new office buildings. While the report pointed to the suburbanization of retail as causing the demise of a traditional economic function of downtown, it failed to address the role of various federal and state programs that subsidized growth on the periphery at the expense of the older city. Thus the redevelopment authority’s final report only hinted at the full dimensions of the urban redevelopment program it had undertaken and left unexamined many of the decisions about downtown revitalization and residential renewal that would have long-term consequences for the city and its people.

Lancaster is a small community with a population of 52,951 in 1998. Located in south-central Pennsylvania, sixty-five miles west of Philadelphia, Lancaster was settled in 1729 and chartered as a borough in 1742. Established as a market town for an exceptionally rich agricultural region, beginning in the 1840s Lancaster evolved into an industrial city. The population grew by 200 percent between 1840 and 1880, and doubled again between 1880 and 1920. These years saw the emergence of a downtown retail district as well as a white collar economy defined by attorneys who clustered near the County Court House and the banks and insurance offices that located near Penn Square. By the turn of the twentieth century downtown Lancaster had acquired the attributes of a modern city. Electric and telephone wires looped overhead, horse-drawn wagons and carriages competed with streetcars and automobiles on the newly-paved streets, and during the 1920s a skyscraper, the Griest Building, rose fourteen stories above Penn Square and symbolized Lancaster’s urbanity even as it affirmed the traditional importance of downtown as the commercial center of the county. But for all the boosterism of the 1920s, beyond the central business district the physical fabric of Lancaster was still predominantly that of a Victorian industrial city in which residents were learning to adapt to changing material conditions. In this Lancaster shared striking similarities with Muncie, Indiana, the "representative" American city Robert S. and Helen M. Lynd analyzed in their landmark sociological study, Middletown (1929). "It is not uncommon to observe 1890 and 1924 habits jostling along side by side in a family with primitive back-yard water or sewage habits," the Lynds wrote, "yet using an automobile, electric washer, electric iron, and vacuum cleaner."

An important New Deal study documented the degree to which that older Victorian city persisted in Lancaster. A survey of real estate undertaken by the Works Progress Administration in 1936 revealed that despite decades of prosperity and impressive population growth, only one in four city residences had been erected in the previous twenty years. Almost a third of the city’s dwellings were more than fifty years old, while one in three residential structures lacked plumbing, heating, and utilities. As economic conditions worsened in the early 1930s, many owners of city properties deferred maintenance, a pattern that continued through World War II. Thus at the onset of the postwar building boom, many commercial buildings were obsolete, much of the housing stock decaying or worse. In short, Lancaster was an old city whose buildings desperately needed modernization.

As is true of most older cities in the northeast and midwest, Lancaster’s population peaked in 1950, when it was home to 63,774 residents, more than 98 percent of whom were white. At that time it retained a thriving industrial economy and a prosperous downtown retail trade. Over the next thirty years, three major changes occurred. The first was demographic. The white population, 62,651 in 1950, declined to 44,373 in 1980, a loss of almost 30 percent. Lancaster’s minority population in 1950 was a small African American community of 1123 with deep roots in the city; in 1980 the black population had increased to 3979 but was smaller than the Hispanic population, 6540 residents, virtually all of whom had arrived in Lancaster in the previous twenty years. Together, African Americans and Hispanics (10,519 residents) represented 21 percent of the city’s population in 1980. The second major change was the loss of the city’s traditional economic base: deindustrialization cost the city 2200 manufacturing jobs between 1958 and 1977, while the closing of wholesale establishments resulted in the loss of an additional 500 jobs. The third major change was suburbanization, which was a factor both in the dramatic decline of the city’s white population and in the loss of jobs and services essential to the economic vitality of Lancaster and its people. Between 1950 and 1980 the white population of six contiguous suburban townships grew exponentially, those municipalities becoming a prosperous ring surrounding a declining core. In each of these developments Lancaster’s experience paralleled the trend of other cities, large and small, throughout much of the nation. The decision to undertake a federally and state-subsidized urban renewal program in the hope of eliminating residential blight and solidifying the downtown retail economy during these years also paralleled choices made in other cities.

How Lancaster’s citizens modernized their city would in essential ways shape its future. Whether renewal strategies would strengthen the traditional business district or discourage reinvestment downtown would affect the tax base of the municipality as well as the School District of Lancaster. Whether the redevelopment authority could remove substandard houses and eliminate nuisance uses while maintaining neighborhood stability would determine how effectively the residents affected by renewal adapted to change. Early in the twentieth century the Chicago school of sociology adopted biological terms as metaphors for the city, describing buildings or neighborhoods as blighted, transportation routes as arteries, the city as an organism. Writers and urban planners of the postwar generation continued the tradition, often characterizing renewal as surgery undertaken to remove cancerous tissue and restore the health of the urban organism. An important recent study of urban revitalization in the post-World War II era, for example, characterized blight as "this malady destroying the physical tissue of urban America" and as the "archfoe of older central cities." Whether Lancaster would rely on the surgical scalpel or the more blunt instrument of clearance, the bulldozer, whether its actions would be curative or destabilizing, would determine how well the city and its people would thrive at the end of the twentieth century.

Urban renewal was a redevelopment program established under provisions of the U.S. Housing Act of 1949 and state and local enabling legislation. Title I of the act gave municipal authorities power to launch a comprehensive assault on urban blight. Under redevelopment law, blight could refer to individual properties or neighborhoods that were physically deteriorating, or defined by small blocks and alleys, or buildings that were simply too close together. Pennsylvania’s 1945 urban redevelopment act, for example, defined blight in terms of patterns of building that did not conform to modern expectations of street width, lot coverage, and open spaces, as well as the "unsafe, unsanitary, inadequate or over-crowded condition of the dwellings" themselves. Blight could also describe buildings or districts where property values or economic uses were declining. In many older cities, such a sweeping definition could be applied to entire neighborhoods and large areas of downtown; in Lancaster it described almost the entire southeast quadrant and much of the rest of the municipality.

After designating an area as blighted, the local authority would then acquire the property, either through purchase or eminent domain, and, after clearance and site preparation, sell the assembled tract to private developers for projects "predominantly residential" in character. The Housing Act of 1949 authorized $1 billion in loans to cities, and an annual appropriation to write-down two-thirds of the net cost to the municipal authority—the net cost being the difference between the expense of acquiring and clearing an area and the resale value of the property. Title III established a new public housing program, but like its predecessor, the Wagner Housing Act of 1937, it mandated slum clearance and restricted public housing to the poor. In its containment of the poor from other classes in society, the Housing Act of 1949, along with tax policies and spending programs that subsidized new residential construction in suburbs, was a key component of what historian Gail Radford has termed the nation’s two-tiered housing policy.

Although the Housing Act’s preamble articulated the goal of "a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family," subsequent sections of the law contradicted that noble purpose. The result of its tortuous legislative history and battles between housing reformers, planners, and real estate developers, the contradictory impulses and policies embedded in the act ultimately placed too much discretion in the hands of local authorities. Despite the rhetoric of an overbearing federal presence in urban renewal, in Lancaster as in other communities most decisions were made at the local level. In The Federal Bulldozer (1964), Martin Anderson conceded that while the federal government provided the bulk of urban redevelopment financing, "the actual execution of the project is left primarily in the hands of local city officials." More recently, a study of redevelopment in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota concluded that although urban renewal was perceived as a national program, it was ultimately a local one: "Urban renewal made a vast pool of resources available to cities," Judith Martin and Antony Goddard observed, "but left decisions about where and how to spend the money primarily to local officials’ discretion." In Lancaster, the decisions made by local agencies compromised most urban renewal programs, especially residential projects. The combination of a massive infusion of federal and state dollars and generally ineffectual local governments had disastrous consequences. In a study of redevelopment in postwar Detroit, June Manning Thomas has demonstrated that "weak federal and local policy tools and structures stunted redevelopment." The most important federal initiatives—the urban redevelopment and public housing programs of the Housing Act of 1949 and the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966, which established the Johnson Administration’s Model Cities program—"suffered because of poorly conceived legislation, antagonistic private interests, congressional and presidential indifference, and erratic funding." These impediments to renewal affected Lancaster just as much as they did larger cities.

Urban redevelopment transformed Lancaster: the comprehensive revitalization program planned and implemented by the Redevelopment Authority of the City of Lancaster changed the physical shape of the southeast quadrant of the city and, through demolition, destabilized the city’s African American community; in attempting to solidify the retail functions of the traditional central business district, redevelopment dramatically altered key blocks of the downtown, replacing handsome turn-of-the-century Beaux Arts structures with modernist concrete boxes and a sterile public square; and, ultimately, urban renewal affected the quality of life and desirability of distant neighborhoods as well. Perhaps it is a reflection of how desperate planners and elected officials were to stop what they perceived as decline and get Lancaster moving forward again, but during the redevelopment program the city adopted plans, such as Gruen’s proposals for Lancaster Square, that were deeply flawed and in retrospect clearly inappropriate for a historic streetscape. The planners and the local political culture failed Lancaster.

Twenty years after the redevelopment authority closed its offices, Lancaster is a much different place than it was in 1980. If many of the buildings look the same, residents are poorer, more diverse ethnically and racially, and live surrounded by crime and evidence of societal breakdown. At a time when Lancaster’s suburbs are growing rapidly and enjoying a prosperity unmatched in their history, cutbacks in federal and state programs have left the city with few resources to redress physical decline and to promote human welfare. By every standard imaginable, Lancaster is at risk.

The following chapter analyze intersections of local culture and a political framework for redevelopment that was determined elsewhere, in the national and state capitals. Both the local perception and the national context are essential to understanding the impact of redevelopment. Geographer Peirce Lewis has observed that cities and towns are "creatures of very particular cultures and very particular histories." Lancaster’s experience with urban renewal was indeed a product of particular circumstances. It was shaped by local actors who determined what areas were designated for redevelopment, who decided what steps would be taken to relocate households and businesses affected by those decisions and what new construction would define the cityscape. These choices were not absolute, of course, for federal and state policies defined the range of options available to public officials and private leaders. Moreover, federal and state bureaucrats evaluated funding applications and attempted to ensure that communities across the nation complied with programmatic goals and policies. But in the interplay of local decisions and federal and state policy, Lancaster’s elected and appointed officials largely determined what happened to their city: despite the plague of "institutional modern" buildings that visibly identify redevelopment areas in Lancaster as in other cities, urban renewal was a locally-directed program that occurred in a specific place.

If the problems Lancaster confronted were similar to those experienced in urban areas across the nation, the solutions its redevelopment authority adopted differed from those of larger cities in terms of scale. How small and medium-sized communities such as Lancaster attempted to halt urban decline and attract downtown the new commercial developments that were spiraling outward from the center is an important though largely unexamined component of our recent history. Indeed, as geographer Wilbur Zelinsky has pointed out, "We know surprisingly little about the form and appearance of the vast majority of the cities and towns of North America," the thousands of small cities and towns that are familiar parts of the American landscape. This study is the idiosyncratic story of a specific community, yet it also presents Lancaster as part of a larger mosaic of policies and trends that have reshaped metropolitan America since World War II.

If this story resonates with the experiences of other places, it is because there is something of more than local importance in Lancaster’s urban renewal program. In the preface to Main Street (1920), Sinclair Lewis noted that Gopher Prairie’s Main Street was "the continuation of Main Streets everywhere." The novelist maintained that his "story would be the same in Ohio or Montana, in Kansas or Kentucky or Illinois, and not very different would it be told Up York State or in the Carolina hills." Lewis’s claim is seductive to anyone undertaking a study of a single place, for it asserts a universality to the author’s conclusions. Lancaster may not be Main Street transcendent, but in crucial ways its experience was representative of national trends, especially the postwar suburban boom, the persistent pattern of segregation that has afflicted metropolitan America, and, ultimately, the tragic consequences of public policy and private attitudes toward African Americans.

For all the similarity of the problems most older American cities encountered in the post-World War II era, Lancaster commenced its experience with urban renewal long after programs in larger cities were underway. Surprisingly, Lancaster’s elected officials, administrators, and civic leaders appear to have learned little from other places about what makes downtown a successful destination or how to revitalize an old residential area without destroying residents’ sense of community. The effort to redevelop downtown Lancaster differed from that of many larger cities because the debate over the future of the central business district in the 1950s did not produce pro-growth coalitions that championed clearance and new construction. As a whole, owners of downtown stores were unprepared for the new competition from suburban retailers. There was not a concentration of large banks, insurance companies, and real estate service corporations downtown, institutions that, in larger cities, had a vested interest in revitalization. Leaders of the city’s most important private non-profit institutions, especially the hospitals and Franklin & Marshall College, did not act as if what happened to the central business district was vitally important to the city as a whole, nor did the owners of Lancaster’s largest manufacturing companies, most of which were located along the northern boundary of the city. Lancaster traditionally has been a non-union community, so what in other cities was a mobilized constituency within the pro-growth coalition was also missing. This may explain the city’s inability to build a downtown expressway, a transportation artery advocated in a number of planning studies. Without a powerful pro-growth coalition the political costs of the massive dislocations an arterial highway would have necessitated were simply too high.

In the absence of such powerful groups influencing municipal policy and directing public and private investment toward downtown, Lancaster, and many smaller cities, had to rely on redevelopers from larger cities who sought to profit from redevelopment. Unsurprisingly, when potential retail tenants decided to locate in suburban malls, the Lancaster redevelopment authority, like its counterpart in similarly sized cities, proved unable to bring its urban renewal projects to a successful conclusion. The downtown, especially, lost its traditional retail function to suburban malls without capturing a significant percentage of the increase in office and professional employment the metropolitan area enjoyed. As a result of the failure of commercial renewal, Lancaster has not experienced the prosperity that major downtowns have enjoyed in recent years—the gleaming skyscrapers, the hotels, festival marketplaces, gentrified neighborhoods, and other monuments of the construction boom of the 1980s and 1990s, which attract tourists and generate much needed tax revenues that sustain the municipal government. Visits to other cities, especially in the northeast, suggest that what happened in Lancaster occurred elsewhere as well. Reading, Pennsylvania, Newburgh, New York (where I grew up) and other mid-Hudson Valley cities that have experienced tragic decline, once-prosperous industrial cities throughout Connecticut and the rust belt along the Great Lakes—all testify to national trends such as urban population loss since 1950, white flight, deindustrialization, and crime. All bear the scars of a changing metropolitan economy and the failure of redevelopment programs to secure a better future for their respective communities.

In yet another way urban renewal in Lancaster was representative of the experiences of many other communities: it took place in a city with a long history of segregation. The neighborhood in southeast Lancaster occupied by minorities included buildings that were among the oldest in the city, and because segregation severely circumscribed the areas where African American residents could live, the small houses tended to be overcrowded. Many, owned by absentee landlords, were poorly maintained. Segregation framed the boundaries of the neighborhoods designated for residential renewal, which had a devastating impact on the city’s African American population. Worse, as a number of dwellings formerly occupied by minorities were demolished, the pressure on nearby blocks increased as African American and a rapidly growing number of Hispanic residents sought decent places to live. As the minority population moved outward from the small area that traditionally had been home to the city’s African American residents, the dominant community’s longstanding hostility toward citizens of color precluded a rational discussion of scattered site low income housing or other measures that might have resulted in an orderly end of segregation and the emergence, over time, of a fully integrated community.

The story of urban renewal in Lancaster, as in other cities, raises unsettling issues of race and discrimination. The experiences common to African Americans only a generation ago seem foreign to many Americans, the majority of whom live in suburbs, and especially to their children. Education and experience have taught the rising generation that segregation was a Southern phenomenon which ended with the Civil Rights movement. Few whites admit the extent to which it existed in northern, midwestern, and western cities and how long it persisted. As a nation we need to recognize that public policies adopted twenty-five and thirty-five years ago continue to affect the lives of minority residents, in Lancaster as in other American cities. Local decisions to undertake residential renewal in specific neighborhoods, and to build public housing projects in the same areas, remain as physical facts that continue to define the places in which individuals live, continue to circumscribe opportunities for educational, occupational, and social mobility. We need to confront the inequities of the past to understand the shape of our society today. In A Place to Remember, historian Robert R. Archibald describes efforts to preserve the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, an institution in St. Louis that trained generations of African American medical professionals. To most white residents of the city the hospital existed outside the realm of everyday experience, and to younger blacks it stands as an abandoned shell, a building without meaning. Archibald believes that the hospital has to be more than a historic building: it must exemplify decades of African American achievement in the healing arts and stand as a reminder of the community’s segregated past: "our city cannot heal," he asserts, "until this place, its people, and its surroundings become a symbol shared by all St. Louisans."

Lancaster does not have a building that symbolizes the historical experiences of all its citizens, nor does it appear to be seeking one. Instead, the current mayor has spearheaded the acquisition of a historic carousel that once operated as part of Rocky Springs, an amusement park in nearby West Lampeter Township. He hopes to place the restored carousel in Lancaster Square, the centerpiece of Victor Gruen’s plan for a revitalized retail district. No one in City Hall seems to think it incongruous that a carousel from an amusement park with a segregated swimming pool—an amusement park that actually closed rather than integrate—should occupy a prominent public space downtown. Memory is elusive: most of the individuals involved in raising money for the carousel recall happy moments from their childhood but accept those recollections uncritically, disassociate their experiences from those of racial minorities. For many older members of the city’s African American community the carousel is a poignant reminder of a time when discrimination was overt, when segregation in housing was nearly absolute. To black Lancastrians the carousel does indeed have a powerful symbolism, though not one shared by most white citizens.

Ironically, for all the pride many citizens take in their community’s long history, few discuss recent developments, let alone analyze how the city has changed and why. Most residents think of Lancaster as a unique place even as its pattern of urban decline and suburban prosperity makes it resemble Anyplace. In explaining the limited success of urban renewal in Lancaster, the redevelopment authority’s final report conceded that its story was not unique. The text emphasized not Lancaster’s singularity but the universality of its experience with urban renewal. The "problems encountered were not Lancaster’s alone," the report acknowledged, "and the lessons learned in the past 19 years have been the same lessons learned across the country." In compelling ways Lancaster’s experience is the nation’s drama, played on a local stage.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.