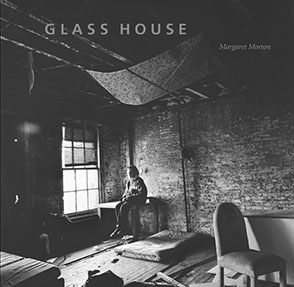

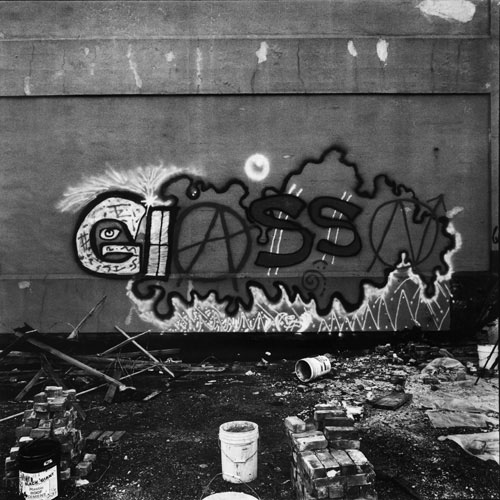

Glass House

Margaret Morton

“Margaret Morton’s Glass House is an important, richly evocative, and very moving book. It may be an illustrated work of oral history, but it has the momentum of narrative. The characters come fully alive and most become quite attaching. Even if we’ve known all along that the story will end with a violent eviction, by the time the end comes it is still shocking.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Your books—The Tunnel; Fragile Dwelling; Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives; and now Glass House—always use a place in their titles and often present photographs of sites throughout New York City. Why these titles? Why so many photographs of the places where the homeless gather to find shelter?

From the beginning, my work was devoted not to despair but rather to the courage and imagination with which people face adversity, the ways they manage to build makeshift structures and find warmth and community. I try to show that the term "homeless" is a misnomer that blinds us from seeing how people preserve their sense of home and identity while struggling for survival at the margins of society.

How does Glass House fit into your earlier work?

Unlike my other books, which are about adults, Glass House focuses upon a group of young people—some were runaways—who in 1993 established a communal home in an abandoned glass factory on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

How did you find out about Glass House and get access to the community?

I learned about Glass House from a homeless man whom I had photographed. He introduced me to Gentle Spike, one of the members of the community, who told me to meet him at Avenue D and East 10th Street on a Sunday night at 9 pm. "If no one is there," he said, "just yell 'Glass House.'" When I arrived at the seven-story building that next Sunday, it was completely dark and looked deserted. I waited a few minutes, then yelled "Glass House." Silence. I yelled again. Suddenly, a thick chain came hurtling down. I had the keys. I found my way to the second floor and a dimly lit, unheated room where about thirty-five people between the ages of seventeen and twenty-two were conducting what they called a "house meeting." "A stranger, a documentarian," was on the agenda. I showed them a copy of my first book, Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives. Discussion, a show of hands, then a woman slammed a sledgehammer on a table: I had been given permission to take photographs and conduct interviews as they continued their lives in this derelict brick building. After that night and for the next four months, I attended Thursday workdays, Sunday night house meetings, and met with individual residents.

Why do you think they accepted you?

These young men and women in Glass House had had many adults—teachers, parents, police—try to impose codes of behavior on them that they considered cruel or irrational or just too restrictive. I think that from the first they understood I would not judge them by society’s norms of conduct. I accepted them as they were. Then, too, I believe the people in Glass House wanted to tell their stories, to present their experiences to a society they thought had been unwilling or unable to understand them. They decided they could trust me to record their way of life.

Glass House seems to have been a tightly regulated community, indeed, seems to have been better organized than most communities and institutions on "the outside." How did they go about keeping order?

They took turns doing essential duties, built what was needed with what they could find, and took care of one another. Each and every one was required to respect house rules, which were strict and detailed, covering almost every eventuality from overnight guests to police raids. Here, for instance, is the guest policy: "You can’t stay at Glass House unless you are the guest of a member. If you are the guest of a member, you can only sleep in his or her room. Glass House is not a crash pad. You can’t sleep in the community room or in any other part of the house. All guests must attend Sunday night meetings, so we know your face. Any strangers will be escorted to the door.

You photographed Glass House from 1993 to 1994. Why did you wait so long to publish the material as a book?

Four months after I began my work, the police stormed the building and evicted everyone. I put aside my photographs, transcripts, and notes and turned to other projects. Then, a few years ago, a letter from one of the Glass House survivors prompted me to trace all the other former residents. I was saddened to learn that five of them had died, and impressed that many others had dramatically changed their lives. One now lives in a eucalyptus forest on Maui; another is an organic gardener in Costa Rica; yet another is preparing for law school. But all I contacted told me that their months in Glass House had been a turning point in their lives. Also it seems right to present this chronicle of young squatters at a time when gentrification is erasing virtually all traces of the ethnic groups and radical fringe that once gave Alphabet City such great diversity and vitality.

“Margaret Morton’s Glass House is an important, richly evocative, and very moving book. It may be an illustrated work of oral history, but it has the momentum of narrative. The characters come fully alive and most become quite attaching. Even if we’ve known all along that the story will end with a violent eviction, by the time the end comes it is still shocking.”

“Margaret Morton’s Glass House is a remarkable work, the best of her books on the demi-monde of homelessness and squatting in New York City.”

“Margaret Morton has been doing remarkable, indeed invaluable work at the juncture of photography and social documentation. She is our modern-day Jacob Riis. Glass House, her latest project, is a triumph of art and compassion.”

“Glass House, which documents a squatters’ community on New York’s Lower East Side, is Margaret Morton’s fourth book about the makeshift homes built by the city’s homeless population. Since 1989, Morton has honed her skills photographing, interviewing, and presenting the compelling stories of people living on the margins of society. Her commitment and passionate advocacy justifies comparison with Jacob Riis, the great nineteenth-century photographer and social reformer.”

“Ms. Morton’s pictures depict a cozy communal home with more graffiti and less Ikea furniture than the Alphabet City of 2005.”

“Margaret Morton’s Glass House is a remarkable, lavish oral and visual history of the titular radical-occupied derelict building (squat) on New York’s Lower East Side from 1992 to 1994. The occupants, a crew of ‘dirty punk rockers’ and hardened street people, proved startlingly disciplined and ingenious in building their communal squat, engaging in elaborate ruses to hide their occupancy from Giuliani’s gentrification-minded police. Although their ignominious ending seems foreordained, the story proves a disturbing alternative narrative in the face of commodity-based urban hipsterism.”

“When I suspended judgment, through Morton's sensitive words and images, I could share in the rich humanity of their lives. Glass House the book is a success as engaged journalism, as photography, and as a tribute to a fascinating social experiment.”

“Morton's black-and-white images are crisp and unblinking.”

Margaret Morton is a photographer well known for her work with the homeless of New York City. Her photographs have been exhibited in numerous one-person and group shows in America and abroad. She has published several books of photographs and oral histories, including Fragile Dwelling (2000); The Tunnel (1995); and, with Diana Balmori, Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives (1993). Morton is Professor of Art at The Cooper Union.

Contents

Prologue

Foetus

Glass House

Tyrone and Chad

Lisa

Donny

Erica

Calli

Scott

Chad

Angela and Markus

Angela and Markus with Friend

Garth and Chad

Toby and Calli

Dumpster Diving

House Rules

Heidi and Scott

Security

Communal Living

Disputes

Drugs

Kim

Chad [Rat]

Moses

Lisa

Scott

Merlin

Heidi

Garth

Mark [Gentle Spike]

Mark’s Sculpture

John

Angela

Calli

Exodus

Linda

Toby

Toby and Erica

Erica

Karl

Donny

Premonitions

February 1, 1994

Joeleyn

Calli, Maus, and Angela

Epilogue

Memorial to Merlin

Merlin Place

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Foetus

Several of the squatters who would establish the Glass House community first met in a nearby abandoned apartment building on East Ninth Street in the late fall of 1990. Finding mounds of baby clothes in one of the rooms, they called their new home “Foetus” and began to repair the neglected building. On October 10, 1992, a fire broke out in the ground-floor stairwell of Foetus squat.

Scott: It was a nice, sunny Saturday. Everyone was outside. We had eaten a soup-line lunch, then I went back to Foetus. I was working on joint-compounding and taping my ceiling and listening to Sly and the Family Stone on my roommate’s tape. I started to smell smoke, then I heard my roommate’s voice coming up through the stairs, “Fire, fire! There’s a fire downstairs!”

I yelled, “Let’s grab a couple of piss buckets and put it out.” I started running downstairs with the piss bucket and got no lower than the third floor when I saw flames starting to come up through the joists. I was engulfed in black smoke and I couldn’t breathe. I decided I shouldn’t go down any further. I’m just going up. I went up to the roof, over to the next building, down through that building and out. People were outside trying to put the fire out. Everything’s burning down. Then the cops and the Fire Department come, and we’re yelling, “Put the fire out! Put the fire out!” And they’re yelling, “Get back! Get away from here!” They just let it burn.

But when the fire started to spread to the building next door and the apartments behind it, they put it out. It was a big fire. The heat was incredible. There were no ceilings to stop it, so it spread really quickly through the back of the building and just went right up to the roof. Someone had kerosene heaters, and all of a sudden there was a big explosion in the back of the building that knocked out windows in the apartments behind it.

The cops wouldn’t let us come back to get anything from inside the building—they had guards out in front almost twenty-four hours straight—so we had to sneak in. We had to go through the garden lot on our bellies and crawl up the back of the building, which had been blown up and collapsed, crawling up the debris to get back into the front apartments. I just grabbed a few clothes and some tools and left.

Kim: People said, “You want to come? You can live at Glass House.”

By 1973, the General Glass Industries Corporation had vacated its two buildings on the southwest corner of Avenue D and East Tenth Street. The attached five- and six-story brick buildings, which had teemed with light manufacturing activity since the early 1900s, quickly fell into decay. Drug addicts and alcoholics increasingly used the buildings as a crash pad in the following decades.

On October 10, 1992, several young squatters arrived at the deserted factory after the fire destroyed Foetus, the abandoned apartment building in which they had been living. They claimed the massive space as their own, clearing piles of debris, constructing walls, and creating living areas for themselves. They called their new community “Glass House.”

<CT> Glass House

Calli: After Foetus burned down, people moved in here and things started happening. Glass House started to become a real squat and not just a bunch of lazy punks.

Moses: Up until then, Glass House had been just a few people who got kicked out of Foetus. Foetus had been the real meeting point for the young squatters of the neighborhood, and, after the fire, Glass House inherited that. A lot of good people came into Glass House from Foetus. Scott came from Foetus. People started organizing themselves. And that’s when the change started, too.

Donny: When we originally opened the place, there were huge piles of pipes, tons of plastic rubble, and a big mess of garbage—all kinds of junk. There was no electricity. There were no toilets. There were no windows. The six-floor building had a bad roof problem. If we hadn’t replaced a couple of joists, the building would have collapsed. You had rotting roofing holding up broken joists rather than the joists holding up the roofing. It never would have survived last winter, let alone all the snow this winter.

The building had existed as a very low-level-activity flophouse where homeless people, winos, drug addicts, whatever, would slip in and out, crash from time to time, get thrown out, then stay there for a while again. This had gone on for years. There were mattresses laying here and there, nests. The building had a really wild time of it the first few months I was there. A couple of people were using it as a crash pad, then other people were moving in and trying to make a serious squat out of it. There were lots of new people flowing in and out every night.

Kim: The place was totally trashed. There were no laws. That winter there were so many junkies living there that we just kicked them all out one night. One of the guys came home totally fucked up and was starting shit out in the hallways. We tried to break it up, and he slapped me. I said, “Look, if you slap me one more time, I’m going to have to hurt you.” He slapped me again. He was totally wasted, so I just threw him down the stairs, and he went and passed out somewhere.

Later on, about six in the morning, one of his friends came back with a baseball bat, smashed my stereo, and hit me and my friend on the head. So we just went around, woke everybody up, went over to C Squat to get more people, and threw all the junkies out. We knocked on their door. They had it barricaded and locked. We told them, “There’s twenty-five of us out here. You can either leave peacefully or it can be a problem.” There were only eight or nine of them, so they got their stuff together and we escorted them to the door. We had pipes and two-by-fours, but no one had to use them. The next day they jumped Karl in the park and broke his glasses, but after that they never bothered us again. That was a big turning point for Glass House.

After this stuff happened with the junkies, we were all really close, we all got to know each other pretty well. It was a big motivating thing because we had done something that was major, really important. That was when the workdays really started rolling. We were having three workdays a week, really working hard. We did a lot of work on the roof because there was a big sinkhole on my side of the building. We went up there, took out all the joists and replaced them. We ran electricity in the hallways.

Donny: We got electricity from a street light on the corner. In the middle of the night, we cut a trench in the seam of the sidewalk with a pick. We put the cable in and cemented the whole thing back over by morning.

Chad: And every time the “Don’t Walk / Walk” sign would blink, our lights would dim.

The squatters hammered through concrete block and mortar to reopen windows that had been sealed shut for twenty years. At night they covered the window openings with black plastic to conceal their electric lamps.

There was no water supply. The squatters made nightly trips to a nearby fire hydrant, using a large plumber’s wrench to force it open. They installed a kitchen sink, which drained into an empty joint-compound bucket. Glass jars and plastic buckets provided the only toilets for the first few months, until Kim and Moses installed two “bucket flush” toilets on the ground floor.

The building needed constant repairs. The roof was so damaged that rain poured through the upper floors; in winter, icicles hung from the ceilings. Loose bricks fell to the pavement from the crumbling parapet, causing potential danger to passersby and possibly attracting attention from the city’s housing agency.

The squatters salvaged discarded building materials from dumpsters and renovation projects. A nearby lumberyard donated warped two-by-fours and drywall. Bright blue planks from police barricades, found alongside construction sites and parade routes, were put to use as replacement stair treads, joists, or trim for loft beds.

Maus: I did so much work, cleaning out the airshaft, building spaces, everyday chores like getting water and cutting up firewood for the woodstoves.

Lisa: If you wanted to live in Glass House, you had to devote yourself to the amount of work that was required, and that’s not something you had to do in a lot of other squats. The building was in really bad shape, and one of the conditions for living there was that you had to build your own space. People had put in a lot of time and effort. I haven’t seen any degradation to any of the properties that squatters have been in; I’ve only seen renovation. I think that Glass House was people taking it upon themselves to do something about all these empty buildings that are just standing there—nobody’s using them—and then there’s all these people out on the street with no place to live. Glass House was a statement that what was happening, that nobody is allowed to live in this empty housing, is wrong.

Calli: It’s not something we’re paying for with money. We’re really putting it together. It’s stuff that we find and we hammer and clean and straighten up. You see that this is your house. You’re building something. You’re building your home. I see the walls not being held together by brick and cement, but being held together by everybody’s hands and everybody’s hearts.

Donny: There was a lot to Glass House. That’s why it had so much heart. It was the biggest building squatters have taken over down here in years. I watched people change and grow up there. It was a transforming experience for a lot of people. I saw people come here with no skills, who learned carpentry, who learned plumbing, learned electricity, and learned installing locks, right here. And some of them beat ten-year, five-year drug habits while they did it. Basically, the family mattered more than the building. I mean we were always working on the building, but we were always working on the community too.

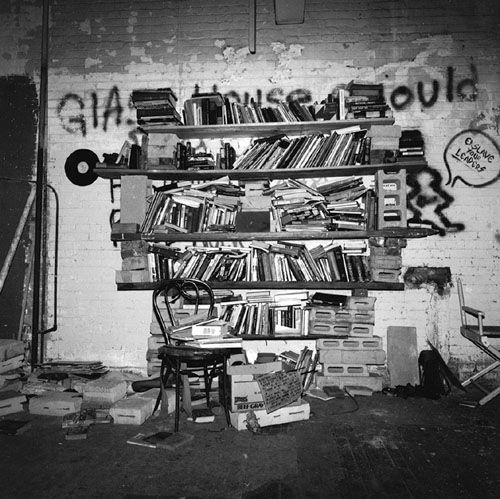

The two thousand square-foot community room on the second floor, the first public area to be developed, became the nucleus of Glass House. Residents built a makeshift kitchen around the sink and added a plywood counter, which they decorated with graffiti. The corner street lamp powered a two-burner hot plate and a toaster oven. In the light of a bare bulb clamped to a metal pipe, they prepared meals of spaghetti, rice and beans, or lentil soup and ate on a round metal table they had found discarded along the sidewalk.

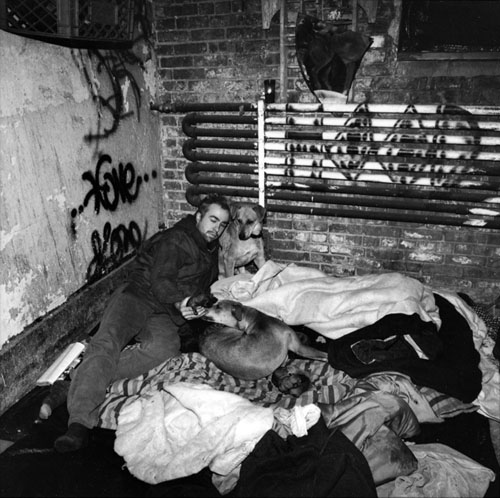

Opposite the kitchen, they clustered chairs, a sagging couch, and a low table—all street finds. A small television sat nearby, topped with a radio and a cardboard dispenser filled with condoms. A precarious arrangement of wood planks and cinder blocks held a large assortment of books.

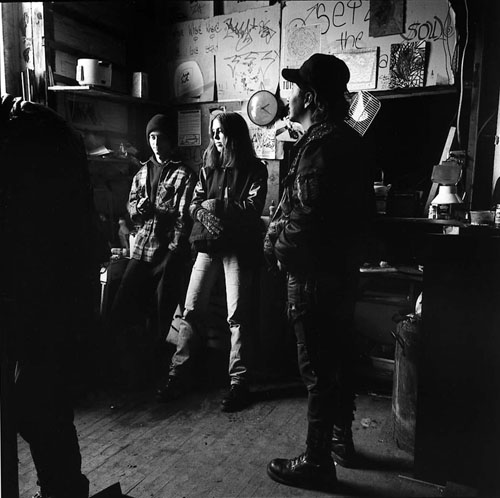

The community room functioned as an informal gathering place where the squatters met casually for meals, to play chess, listen to music, read, sew, or discuss politics. They also assembled there for scheduled Sunday night house meetings and Thursday workdays.

Kim: After the community room got built, everything got rolling. That first winter, it was like a family. And that’s the way it should be, because we had a lot of younger kids who didn’t have a family at their own home, so why not come to a home where they could have a family of people who respected them and were their equals.

<CT> Dumpster Diving

“Dumpster diving,” was a nocturnal expedition in which squatters raided the food discarded by Upper East Side restaurants and grocery stores.

Moses: We were good. We got this guy with a truck turned on to the idea. He would take us twice a week and just take a cut of the food for himself. We would go up First Avenue to the upper Sixties and down Second Avenue. We would go at ten o’clock at night, because that’s when the stores close and they put out the garbage for the next day.

It was kind of like a SWAT team. He would just slow over to the curb and we would all jump out. We would stop at all the grocery stores, Hot & Crusty Bakery, and all the health food stores. One time we found eight wheels of Brie, totally unopened. We would just go for the trash—tons of fruit and vegetables, milk, butter, cheese, bread, yogurt, ice cream—just thrown out on the street.

If we had a good night and had way more than we could handle, the guy would just drive the truck up to the different squats and we would drop food off. Everybody you went to visit would be eating the same thing for the next week.

Karl: Sometimes when I’m really hungry and broke—dumpsters. There are places uptown that are just teeming with food. There are places that are unreal. During the convention summer, ’92, friends went out dumpster diving and they found a bagel shop in the Eighties where they threw out bagels that were still hot, just a little defective. But I like the D’Agostino’s on University Place and Gristede’s, that’s where I usually go. I’ve literally found whole chickens thrown out. Me and my friend found beer, ice cream, all kinds of amazing things. Pies. Might have a little mold. Cut the mold off, they’re still good. Literally kept me from starving. So much food is wasted in this country, it’s amazing.

Besides dumpster diving, I look on the street. You might be walking down the street, you see a bag sitting on the side, kick it. If it has weight to it, pick it up, look inside. It could be beer. It could be food. It could also be dog shit. You take the chance.

<CT> House Rules

By the time I first visited Glass House in the fall of 1993, twelve women and twenty-six men, most between the ages of seventeen and twenty-one, had moved in. The group had established mandatory house meetings and rules for membership and maintaining the building. Membership was by invitation only and membership requirements were strict. Squatters with carpentry skills commanded respect; they organized and trained workday crews and exerted influence at house meetings. Newcomers literally worked their way into the house.

Toby: Thursday workdays were always really important. You had one month to do four workdays, then they would decide if you could have a space to build. You had another four weeks to do enough work on your space to show that you were making progress, and then they voted whether to give you a key. And I won. I got a key. So then I was a member.

Glass House was more organized than a lot of other houses I’ve lived in. At other houses, they just called a meeting when they needed one. At Glass House, every Sunday night at nine o’clock, everyone got together in the community room and would talk. It was good because you got to see who you lived with and really talk about changes and things. Dues were a dollar a week minimum, but you could give however much you wanted, or pay monthly. I’d give them ten dollars, here or there, or whatever I had.

Kim always took over at house meetings, wrote the agenda, kept track of attendance, and everything. It just kind of happened. Some people have more of a leadership quality than others. She and Moses were good at finding things that needed to be done and then doing them. I’m sure that was really stressful, trying to take on that whole responsibility.

Moses: We had the idea that, if we could work together as a group, we could live at a better level of subsistence than if we were all separate, so we started having meetings. The rules came about after a lot of discussion at house meetings, and we changed them a few times. Right before the summer, we came up with the rule of four workdays followed by thirty days to build a space, and it seemed like something that we really wanted to try to stick to.

Angela: I ran away from home to escape all the rules. There were even more rules at Glass House.

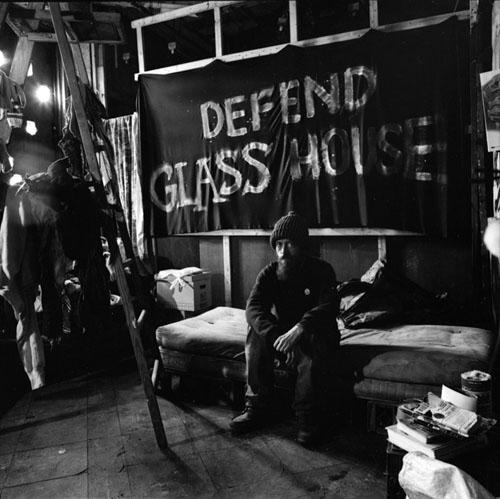

<CT> Security

Protecting the house from police investigation was a major concern of the squatters. At house meetings, they organized four means of security: night watch, bike watch, eviction watch, and barricade crew. Sign-up sheets were posted on the community bulletin board. All members were required to participate on a regular basis. Those on night watch maintained a midnight-to-dawn vigil at the front door. A sign on the community room bulletin board provided them with detailed instructions.

IF YOU ARE ON WATCH AND. . .

1. THE COPS COME . . .

1) Notify those who are in the room to wake people up, call Eviction Watch, and to put up barricades.

2) Do not touch any papers! Ask to see a ranking officer. Be respectful and polite. Have him read any names on the eviction notice. Tell him they do not live here.

2. THE FIRE DEPARTMENT COMES . . .

1) Notify those who are in the room to wake people up, call Eviction Watch, and to put up barricades.

2) If they say they need to inspect the building: Tell them a lot of people are not home. Ask for a phone number where our lawyer can call to make an appointment.

3) If they are serving papers: same as #2 above.

3. ANY INSPECTORS COME . . .

1) Same . . .

2) Same as #2 above.

In addition to Night Watch, members were expected to serve on one more security “crew.” Bike Watch was a pre-dawn reconnaissance mission to local police precincts and public parks, where police had congregated for previous evictions. The cyclist on duty extended surveillance to other squats as well. Should an eviction be in progress, members of Glass House would go to their aid. Any threatening police activity was immediately reported to the Barricade Crew, which was then responsible for securing the front door and sealing off individual floors. “There are two front doors that are back to back,” said Donny. “The inner one is barricaded. There are two more barricaded doors between the rooms on the ground floor and a barricaded stairwell before you can gain access to anything other than the first floor. There are even barricades to seal off each floor.”

Eviction Watch was a security cooperative organized by several squatted buildings that agreed to band together to help one another in case of danger. Each squat was responsible for contacting one other nearby squat in a chain designed to alert all participating buildings within ten minutes. Members rehearsed the communication system monthly and occasionally put it to the test.

Moses: I had just moved in and was walking back to the building with three friends. Some kid that lived there was standing in front saying, “Don’t go in there. The cops are trying to kick the door in.” We ran and alerted Eviction Watch and yelled to the other squats. I’d never actually experienced getting Eviction Watch in motion before, and we did it. Within ten minutes there were at least fifty people in front of the door. Everybody got up on the stoop and locked arms, blocking the door. More police started showing up and soon there were ten cop cars. All of a sudden, there was this big standoff. But the people there were really strong. It turned out that the police had been told that a person with a gun was seen entering the building. It was only someone who had been working on the door with a screw gun, but there was a big confrontation until somebody explained it all to the cops. The cops saw that they would have to arrest thirty people to get in, so they just left. That was it. It was a victory. It made me feel really good about the security of Eviction Watch and its ability to work. And it definitely added to my love of the building. At that early point I already felt like I had a stake in it because I’d been involved in a victory.

Despite elaborate security precautions, the group decided that, with so many new members, they could not keep secret their occupancy of the building. At the Sunday night meetings, they voted on rules of conduct and cautioned any members whose activities might attract police attention.

Underage runaways were not allowed to stay, particularly if there was any suspicion that the police might be looking for them. “That can bring the heat down on the entire building,” Moses said. Glass House members prohibited panhandling, a favored source of quick cash, within a block of the building; neighbors might complain to police. Angela was surprised to be reprimanded at a Glass House meeting for something that she did at C Squat, but cooperation with neighboring squats was essential to the success of Eviction Watch.

Angela: I drank all the time. I did dust all the time. One night I was sitting outside of C Squat doing dust when the cops came by and told me to move along. Then one of the guys from C Squat came out and said, “We don’t want you coming over here doing drugs and bringing the cops to our door.” He must have told people at Glass House, because at Sunday’s meeting Kim told me that I’d better not do drugs outside C Squat again.

When a newcomer jumped through a second-floor window, the fire escape broke his fall. Glass House members did not rush him to the emergency room—police might make a follow-up visit—but they kept vigil throughout the night and made arrangements for his safe return to the Midwest.

Toby: At first Jay seemed pretty normal, just your average person. He wasn’t like a dirty punk rocker. But then he started getting really paranoid.

Erica: He was found in the basement, naked, eating asbestos.

Toby: Then he crashed through the community room window because he thought a bucket was a nuclear bomb. I guess he had decided to stop taking his medication. From what I hear, people who do that get this great high and are really happy for a while, then they come crashing down. Everyone had to get together and deal with this. It was better for him to be back on his medication or go home to his family.

Kim: I think he was schizophrenic. For some reason he had decided that Moses and I were the only ones he could trust. He stayed with us in Moses’ room all night. We contacted his sister and someone came and got him.

Erica: He came back all clean and fancy, got his stuff and left.

Concerns over internal security, personal safety, and private property sometimes caused tensions at Glass House. Some residents felt secure, but others devised elaborate means to protect their living spaces. One member suspended glass chimes across the inside of his door as a warning against intruders. Another member, when he was sleeping or away from Glass House, removed sheets of plywood that spanned the open floorboards in front of his room. Anyone who approached after dark risked falling to the floor below.

At an October house meeting that I attended, Karl asked that a house policy on gun possession be added to the agenda. He reported that, on the previous evening, he had encountered Linda brandishing a .38 caliber pistol in the hallway. Members of the group asked Linda to explain. Unshaken by the question, Linda answered, but was interrupted by the arrival of Christy, with whom she had been having a strained relationship. After some discussion, the group voted with a show of hands; guns were allowed in the house, but could not be used to threaten other members.

Linda: Stuff was disappearing from my room. I tried telling Christy to stay out. I even found my large mirror in her room. Finally I had to stick my piece in her face. It was the only way it was ever going to sink in. I don’t understand why this is house business. It’s between me and her. What are you so worried about, Karl? It wasn’t for you.

Karl: It may be between you and her, but I’m the one who ran into you with a gun in your hand in the middle of the night. I understand your need to make your point, but if that gun goes off, I could get hurt instead.

Christy: I’m not a thief. I woke up in the middle of the night with her gun in my face. My room has to be my sanctuary. It has to be a place where I feel safe. What if I got shot? You would just throw my body down the elevator shaft and my parents would never know what happened to me.

<CT> Communal Living

In addition to membership, workdays, and security concerns, at house meetings Glass House residents discussed general building maintenance and household chores, and arbitrated routine problems of communal living.

Angela: At the Sunday night meeting, the house leaders told us they needed to check us for lice. They didn’t want the lice spreading, so they made us all line up and they checked our collars and stuff. I had some lice. I couldn’t figure out how I had them because I’d just gotten back from visiting my family in Indiana. I was really irritated, and the member who checked me was a real jerk about it. There’s no way to get rid of lice without washing everything, so we ended up getting rid of the couches.

Toby: Once two guys on the fifth floor had been drinking and they started wrestling and knocked over a piss bucket. It seeped down to the fourth floor and got all over everybody. Then one of the guys tried to stab Kim with a fork or knife. It had something to do with Gentle Spike’s dogs peeing down into the guy’s room. He wanted to kill Gentle Spike and all his dogs and puppies.

Maus: The guy above us swore someone was stealing stuff from his room, so he put piss buckets above his door. One night he went out and got drunk and forgot. He set off a piss bucket and all this pee came through our ceiling while we were huddled around the woodstove. We all were soaked and everything smelled terrible.

Toby: After we got bucket flush toilets, you had to go out to the fire hydrant and bring in a five-gallon bucket of water to flush the toilet. A lot of people would try and get away without doing that and the toilets would clog. It was always brought up at the house meetings.

<CT> Disputes

Donny: Most buildings eventually have some period of problems. It’s really hard to find thirty or forty people without problems.

Karl: If there’s an issue that has to be settled, we talk about it. We all vote on it. It’s done by consensus. If someone is gonna get chucked out who we don’t want, who’s screwing up or ripping people off, or is a john, whatever the problem might be, we vote on it and say, “Well, you’re out. Now get your stuff, let’s go,” and we march them to the door. Or, “You’ve got a week to do better,” whatever. It’s all done by consensus.

Moses: The most important thing to me was to keep a decision-making body in the house that was not controlled by one person, which was controlled by the feelings of the whole group. I really wanted to keep that as consensual as possible. If any one person in the house had a serious disagreement or a problem with something, that was enough to make it an important issue. It was like having enough respect for each other that you could be respected by the house. I wanted people to feel that’s where you’d go if you had a problem. You wouldn’t start some fight, or call the police, or whatever, but that you could go to the house meeting and say to the house, “Look, I’ve got a problem,” and the house would react.

Kim: The forum was there for them to voice their opinion. I just wanted everyone to feel secure enough to state it.

Maus: A lot of times younger people exclude older people. But we had Donny and we had Karl. They were just like the parents, and then the kids would fight. It was dysfunctional and it was co-dependent in all those ways, yet I knew we could always talk to each other. I found unconditional love.

<CT> Drugs

The neighborhood was well known as a center for drug trade, and dealers openly proffered drugs on Avenue D and the surrounding street corners. House members voted to prohibit drug use inside the building, and members who ignored repeated warnings risked eviction. Drugs were a heated topic at Sunday night house meetings.

Moses: Squatters get so demonized in the press and by people who live around here, but for a lot of young people, especially urban young people, the two big problems are drugs and violence. At Glass House we did a lot to overcome the drug problem.

Donny: Glass House threw out a couple of junkies, but we also got several people off junk. Because the word is, “Get off or get out.” We prefer they get off. And if the people are strong enough to care more about the community than about junk, that’s great. If you want, I’ll sit up with you all night for a month to get you there.

Calli: I was doing drugs on and off for a while and then over the summer I got really bad again, but they just didn’t want me to leave. They wanted me to straighten up. I’ve fallen down so many times, but I’ve always been able to get back up because of the people there. If I didn’t have so many people there backing me up, I wouldn’t have stayed, because it was hard enough just trying to kick it.

Kim: Calli had been living here a long time and had already kicked dope once. She had been off for a long time when she relapsed. And I knew that she could kick it again. I had got to know her and I liked her. I knew that she deserved a chance, that we could help her, and that she could do it. With other people, I probably wouldn’t have done that. People just coming in, or people who haven’t proved themselves to me, I probably wouldn’t give a shit about. I would kick them out in a heartbeat. But Calli’s a good person, and I know what she’s like when she’s not doing dope.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.