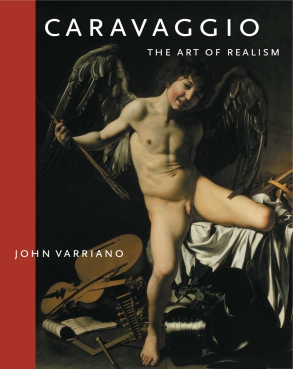

Caravaggio

The Art of Realism

John Varriano

“The scholarship is not just sound, but is up to date and rich, adding pertinent bibliography from other disciplines. The book’s main strength is in Varriano’s levelheaded approach to his subject and his careful, thoughtful, hard look at the images.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Caravaggio’s irascible personality, libertine sexual preferences, and lawless, even murderous, behavior have attracted as much heated commentary as his realism. Varriano sheds important new light on these disputes by tracing the autobiographical threads in Caravaggio’s paintings and framing these within the context of contemporary Italian culture. Ultimately, Varriano links Caravaggio’s aggressive persona and innovative methods to changes taking place throughout seventeenth-century Europe.

Caravaggio: The Art of Realism begins with a highly original investigation of the artist’s studio practices. In subsequent chapters, Varriano discusses Caravaggio’s response to the material culture of his day, his use of gesture and expression, and his eroticism and violence as well as other issues central to the painter’s legendary realism.

Caravaggio: The Art of Realism will appeal to students and the general reader as well as to specialists in the field. Varriano has a gift for presenting complex scholarship in a clear, accessible way. The book contains numerous color illustrations that will help readers experience Caravaggio’s art and follow the author’s informative discussion of such famed paintings as Love Victorious and David with the Head of Goliath.

“The scholarship is not just sound, but is up to date and rich, adding pertinent bibliography from other disciplines. The book’s main strength is in Varriano’s levelheaded approach to his subject and his careful, thoughtful, hard look at the images.”

“The book does an excellent job of looking closely at the paintings, getting us to think about them in new and interesting ways. . . . The degree to which the author will stimulate students to look closely at the pictures is very considerable.”

“[If] the reader is in search of an incisive and well-grounded reassessment of the nature of Caravaggio’s revolutionary ‘realism,’ they should read John Varriano’s engaging study . . . which cogently unpacks the various ways in which Caravaggio must have worked to orchestrate his riveting imagery.”

John Varriano is Idella Plimpton Kendall Professor of Art History at Mount Holyoke College. He is the author of Italian Baroque and Rococo Architecture (1986), Rome, A Literary Companion (1991), and numerous articles and exhibition catalogues on early modern Italian art.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Biographical Conspectus

1. Myths of the Studio

2. Imitation and Imagination

3. The Eye of the Beholder

4. Physical Presences, Erotic Appetites, Wit

5. Violence

6. Portraits and Portrayals

7. Gesture and Expression

8. Settings and Accessories

Conclusion

Notes

Index

Introduction

It was with a student’s question that the idea for this book originated. Some two decades ago, a young woman in my Caravaggio seminar asked why an Islamic carpet was draped over the table in the London Supper at Emmaus (fig. 7). While I no longer remember the name of the student or my response to her question, I do recall that the ensuing discussion made me think long and hard about the carpet. My curiosity about the textile soon extended to the maiolica tableware placed above it. Rarely, it seemed, did Caravaggio’s legendary empiricism allow for such easy verification. With the help of carpet and maiolica specialists—one a colleague and the other my wife—I was able to check the accuracy with which Caravaggio painted the domestic furnishings in both the London and Milan versions of the Supper. I published the results of that study in The Art Bulletin (June 1986) and went back to thinking and writing about Baroque architecture and the city of Rome.

In 1988 and 1990, two rediscovered “lost” Caravaggios were published in The Burlington Magazine. The two pictures—the Cardsharps (fig. 12) in Fort Worth and The Lute Player (fig. 77) in New York are each organized around tables covered by Middle Eastern carpets, which, to my surprise, had in both instances been overlooked. Thinking further about Caravaggio and the decorative arts, I wrote a short essay that appeared in somewhat truncated form as a “Letter” in The Burlington Magazine (August 1992). In it I suggested that the carpets were there to please the pictures’ patron, Cardinal Francesco del Monte, who owned tapetti da tavola himself, rare items at the time. The part excised by the editor was my conjectural discussion of the number of different rugs depicted in the four Caravaggios that feature them. My fascination with the mechanics of Caravaggio’s empiricism began to grow. I started to wonder what, if any, principles he followed when painting from the model. When did he simply depict what he had in front of him and when did he turn to his imagination? When did he look to other works of art for inspiration? The time I spent studying the carpets in the Cardsharps, the Lute Player, and the two Suppers at Emmaus convinced me that these were questions worth pursuing.

Unidealized naturalism was practically all the early biographers like Giovanni Baglione and Giovanni Pietro Bellori saw in Caravaggio’s art. The terms they used were naturalezza (naturalism) or del naturale (after nature), occasionally da vivo (from life) and less often, reale e vero (real and truthful). The word realism only became widely used in the nineteenth century, when it acquired an ideological slant associated with the more mundane aspects of contemporary life. I use realism rather than naturalism in my title because I believe that the “modernity” of Caravaggio’s social iconography—his trademark depiction of dirty bare feet, for example—was every bit as polemical as Courbet’s. I also favor the term realism because it suggests a greater degree of selectivity than naturalism does. It is not my intention to sharpen or even expand these semantic distinctions in an effort to refine our notion of the larger issues of Renaissance aesthetics but simply to focus on the choices made by the painter himself.

If Caravaggio’s early critics mythologized his naturalism, modern art historians have gone on to create myths of their own. Now we find him described as an agnostic, a deeply religious painter, a queer, an esoteric, a criminal, a clever imitator, a psychoanalytical case study, the voice of the new epistemology, and so on. Clearly Caravaggio was a complex and mercurial character who painted passionate and compelling pictures, but it is less obvious how his life and his art were intertwined, or how one should go about appraising the linkage between the two. Indeed, the biography itself is problematic, for Caravaggio seems to have fashioned his public persona as cleverly as the critics did in recasting rhetorical topoi to make points of their own.

The purpose of the essays that follow is neither to create a new myth nor reinforce an existing one about Caravaggio and his art. Rather, it is to investigate the terms of his legendary “naturalezza.” Each of the eight chapters treats an aspect of his art associated with that realism. Beginning with his studio practice (1), the chapters go on to discuss his relationship to the art of the past (2), his engagement of the spectator (3), the realism of his figures, their eroticism, and their wit (4), the violence in his art and his life (5), the pedestrian nature of his portraits and the genius of his disguised likenesses (6), the typically misunderstood subtleties of his gesture and expression (7), and the topic with which my study of Caravaggio began, his response to the material culture of his day (8). Some paintings are discussed in nearly every chapter, while others are scarcely mentioned. Together the essays constitute neither a survey of his paintings nor a substitute for the comprehensive monographs recently published in English by Helen Langdon, Catherine Puglisi, and John Spike.

There is no evidence to suggest that Caravaggio was ever given to theoretical posturing. No letters, no manuscript jottings, and few, if any, reliable firsthand accounts explain what working “from life” might have meant to him. Unlike his followers Simon Vouet and Jusepe de Ribera, who inscribed canvases “ad vivum depicta” or “ad vivum mire depicta” (painted from life or painted marvelously from life), Caravaggio left no such traces behind. Only the transcript from the libel trial brought against him by the artist/biographer Baglione in 1603 gives any indication of the skills he admired in other painters. According to this muddled account, the necessary skills were “knowing how to paint well and imitating natural things well.” However, three of the four painters he named as “having a real understanding of painting” were the late mannerists Cavaliere d’Arpino, Federico Zuccaro, and Cristoforo Roncalli, while the fourth, Annibale Carracci, had by then moved beyond the naturalism of his early days to revive the classicizing idioms of the High Renaissance.

Categorical lists of painters from this period rarely make much sense to the modern eye, as Vincenzo Giustiniani’s famous letter to Teodoro Amayden illustrates. Of the twelve “methods” of painting outlined by Giustiniani (a sophisticated collector who owned a number of works by Caravaggio), working “directly from natural objects before one’s eyes” was only embraced by Rubens, Ribera, and Gerrit van Honthorst, among the better-known artists. Caravaggio, in turn, was grouped with the Carracci and Guido Reni as painters who worked “di maniera and also directly from life,” which Giustiniani considered to be the best method of all.

The artistic climate of Rome at the time of Caravaggio’s residence (1592–1606) was not conducive to theoretical formulations of any kind. At the Accademia di San Luca, the one place where lively debate among artists might be expected, critical discourse was seldom heard. Despite the constant prodding of Federico Zuccaro, the Principe (president) of the Academy in 1593–94, virtually no one came forward to lecture on theory. On those few occasions when someone did agree to speak, they often excused themselves at the podium or failed to appear altogether. As Denis Mahon remarked so many years ago, such theory as existed “was above all literary and interpretive rather than artistic and creative.” Significantly, the treatises that were written by amateur critics such as Giovanni Battista Agucchi (1570–1632) and Giulio Mancini (1588–1630) were not published in their lifetimes. Artists in Caravaggio’s day were not timid about voicing their opinions, especially when it came to the work of rivals, but they did so in private, preferring spontaneous verbal quips to well-formulated discourses. In a legendary remark cited by Agucchi, Bellori, and Malvasia, Annibale Carracci is said to have admonished the public verbosity of his brother Agostino with the gibe “Noi altri dipintori habbiamo da parlare con le mani” (We painters have to do our talking with our hands).

Seventeenth-century biographers and critics occasionally put words in Caravaggio’s own mouth, prefacing statements with an informal “he said.” The most credible of these occurs in a letter written by Vincenzo Giustiniani—arguably his most enthusiastic patron—which quotes the artist as saying that “it was as difficult to make a good painting of flowers as one of figures.” The letter was written ten years after Caravaggio’s death (fourteen years after he left Rome) but the statement actually sounds plausible enough to have been true. However, the remarks attributed to Caravaggio in most biographies sound more like rhetorical topoi than transcriptions of real conversations. Thus in G. P. Bellori’s 1672 Vita, we find that “when [Caravaggio] was shown the most famous statues of Phidias and Glycon in order that he might use them as models, his only answer was to point to a crowd of people, saying that nature had given him an abundance of masters.” How illuminating it would be if that were true, but Bellori’s remark was in fact a paraphrase of a tale told by Pliny the Elder about the ancient painter Eupompos’s own affinity for realism. As Carl Goldstein has pointed out, rhetorical conventions flourished in biographies of this period, not because they were so fanciful but because they tended to encapsulate fundamental assumptions about artistic personalities and the creation of works of art.

The present study questions traditional attitudes toward the realism of Caravaggio’s art. Most chapters begin with the early fortuna critica even when it does not vary greatly from topic to topic. My approach is as intuitive and empirical as I take his own to have been. Like Giotto and other pioneering painters before him, Caravaggio plotted his course without a detailed roadmap. I do much the same in the essays that follow, coaxing meaning out of each topic without relying on preconceived theories or notions of what one should expect to find. I have also made every effort to make the text accessible to students and a general audience. Words like “performative” or “relationality” do not appear on these pages. In fact, it was for readers like the young woman who first inquired about the carpet that this book was mainly written.

Because the chapters are organized topically and not chronologically, readers unfamiliar with the basic outline of Caravaggio’s life should consult the biographical conspectus that immediately follows.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.