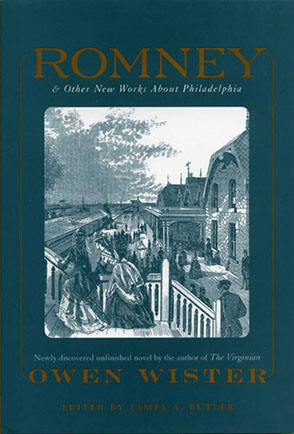

Romney

And Other New Works About Philadelphia By Owen Wister

Edited by James A. Butler

“Romney is a delightfully surprising and important contribution to our understanding of Owen Wister, of Philadelphia and its Main Line suburbs, and of American literature in the early twentieth century. Readers will be intrigued to find that Wister anticipates in this unfinished novel, by more than seventy years, the thesis put forth by E. Digby Baltzell in his Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. For anyone wishing to come to terms with the Philadelphia story, this is a ‘must-read’ book.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Even in its incomplete state—nearly fifty thousand words—Romney is Wister's longest piece of fiction after The Virginian and Lady Baltimore. Writing at the express command of his friend Theodore Roosevelt, Wister set Romney in Philadelphia (called Monopolis in the novel) during the 1880s, when, as he saw it, the city was passing from the old to a new order. The hero of the story, Romney, is a man of "no social position" who nonetheless rises to the top because he has superior ability. It is thus a novel about the possibilities for meaningful social change in a democracy. Although, alas, the story breaks off before the birth of Romney, Wister gives us much to savor in the existing thirteen chapters. We are treated to delightful scenes at the Bryn Mawr train station, the Bellevue Hotel, and Independence Square, which yield brilliant insights into life on the Main Line, the power of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the insidious effects of political corruption.

Wister's acute analysis in Romney of what differentiates Philadelphia and Boston upper classes is remarkably similar to, but anticipates by more than half a century, the classic study by E. Digby Baltzell in Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia (1979). Like Baltzell, Wister analyzes the urban aristocracy of Boston and Philadelphia, finding in Boston a Puritan drive for achievement and civic service but in Philadelphia a Quaker preference for toleration and moderation, all too often leading to acquiescence and stagnation.

Romney is undoubtedly the best fictional portrayal of "Gilded Age" Philadelphia, brilliantly capturing Wister's vision of old-money, aristocratic society gasping its last before the onrushing vulgarity of the nouveaux riches. It is a novel of manners that does for Philadelphia what Edith Wharton and John Marquand have done for New York and Boston.

“Romney is a delightfully surprising and important contribution to our understanding of Owen Wister, of Philadelphia and its Main Line suburbs, and of American literature in the early twentieth century. Readers will be intrigued to find that Wister anticipates in this unfinished novel, by more than seventy years, the thesis put forth by E. Digby Baltzell in his Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. For anyone wishing to come to terms with the Philadelphia story, this is a ‘must-read’ book.”

“Owen Wister’s Romney, edited and annotated with extraordinary precision by James A. Butler, is an unexpected and most valuable contribution to two important matters. One is our knowledge of Owen Wister, through this—hitherto practically unavailable—book. The other is the very content of this unfinished Wister work, essentially a novel of manners, set in Philadelphia society of the 1880s. Philadelphia has been a nearly ideal setting for a novel of manners but, for various reasons, during two centuries few of them have been forthcoming. Romney, unfinished as it is, is a substantial exception-which is why it ought to be read by everyone interested in the history of Philadelphia and of Philadelphians.”

“Romney ought to be read by anyone with an interest in American history, in the price of ‘progress,’ in comic literature, or in the timeless tension between ‘old’ and ‘new’ money.”

“Thanks in great part to superb editing by Butler, this volume is a welcome addition to the Wister canon. Romney would have taken its place alongside The Virginian (1902) and Lady Baltimore (1906) . . . but he never completed it.

The novel occasionally brings to mind the work of Howells, James, and Henry Adams, and Wister’s thesis anticipates the urban-contrast arguments of E. Digby Baltzell’s Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia (1979). Nicely illustrated, with an introduction, notes, chronology, and appendixes detailing other pertinent works, this book is highly recommended at all levels.”

“Like Wharton’s best work, the unfinished Romney, along with Wister’s essays about Philadelphia society, remains striking for its examination of American social pathologies that, despite changes in ethnic, cultural, and technological composition, remain virulently prevalent today.”

James A. Butler is Professor of English at La Salle University, where he is also Curator of the Wister Family Special Collection. He is Associate Editor of The Cornell Wordsworth Series.

Introduction

It may seem strange that Owen Wister, originator of the literary "Western," in his spectacularly popular The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains (1902), should have moved from writing about Wyoming cowpunchers to depicting the rarified upper reaches of nineteenth-century Philadelphia society. In fact, the writing of The Virginian is what requires an explanation, for Wister was not a Western cowboy but an aristocratic Philadelphian, a man who "can lay claim to being the best born and bred of all modern American writers" (Cobbs, 1).

No work by a Philadelphia writer has been more read than Wister's The Virginian, with the possible exception of either Poor Richard's Almanack or the Autobiography by that refugee from Boston, Benjamin Franklin (see Burt, 384). Indeed, some have contended that Wister's story about elemental good and evil resolved in the classic showdown gunfight was read by more Americans in the first half of this century than any other novel.1 And The Virginian, the source of the hit television series of the 1960s and of five film treatments, one starring Gary Cooper in 1929 in his first "talkie," still sells well today in multiple paperback editions. Lady Baltimore, Wister's first novel after The Virginian, was a bestseller book in 1906 and is still in print more than nine decades later. His third and last novel, the Philadelphia one, entitled Romney, survives as a substantial 48,000-word fragment written between 1912 and 1915. The full text of Romney first appears in this volume.2

Owen Wister is one of those rare native Philadelphians who, after achieving national and international renown, stayed on in the city of his birth. His feelings for Philadelphia were mixed, however, especially in his condemnation of character traits that also pervade Romney: a cautious and deadening "Moderation" that produced stuffiness, and a conformity that stifled initiative. As a young man, Wister in his letters and diaries describes the city as "a stupid hole,"3 and "not the place I should choose either for my friends or myself if I could help it" (OWW, 130). As Wister's early Western short stories began to win applause, he confided to his diary that "the only people who, as a class, find fault with what I write are my acquaintances who live in the same town" (OWW, 202). He even began to publish his anti-Philadelphia sentiments: "We of Philadelphia seem to steer wide of this amiable and hasty encouragement. We seem to distrust our own power to do anything out of the common; and when a young man tries to, our minds close against him with a civic instinct of disparagement. A Boston failure in art surprises Boston; it is success that surprises Philadelphia."4 Criticisms of Philadelphia even more barbed appear in Romney and in the various related pieces included below in the appendixes. Wister could see the all-encompassing political corruption that muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens thundered made Philadelphia the most dishonest place in the country, a city "Corrupt but Contented."5 But as he grew older Wister's censures, strongly worded as they sometimes are, sound more like those of a disappointed lover hoping for reformation and reconciliation.

This "Philadelphian of Philadelphians"6 was too deeply enmeshed in the city's social web ever to abandon the City of Brotherly Love. To give just a few examples: he received an honorary degree from the University of Pennsylvania, served as president of the Library Company of Philadelphia and of the Philadelphia Club, became a life member of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and was a member of the Philadelphia bar for four decades. As "Philadelphia's last distinguished gentleman of letters,"7 Wister was a Philadelphian to the core, and in Romney he has left us an indelible portrait of his city in the nineteenth century. Wister sites are strewn throughout the Philadelphia area (especially in the Germantown section), and they tell the story of his privileged life. He was born on 14 July 1860 at 5203/5 Germantown Avenue, near his paternal ancestors' eighteenth-century mansions of "Vernon" and "Grumblethorpe" (the latter dwelling eminent enough to have had British General Thomas Agnew bleed to death on its floor during the Battle of Germantown). The Pennsylvania heritage of Wister's paternal ancestors precedes William Penn's arrival by two months, dating back to Dr. Edward Jones's coming ashore at Upland (now Chester) on the Delaware on 13 August 1682.8 On the maternal side, Wister's lineage is equally distinguished. He was a descendant of Pierce Butler, a South Carolina delegate to the Constitutional Convention, whose namesake and grandson married Fanny Kemble, one of the most famous actresses of the nineteenth century. Wister's grandmother Fanny has been called "the most fascinating and creative woman who ever lived in Philadelphia."9 At the maternal mansion of Butler Place (now gone, but once standing three miles northeast of Germantown), portraits of family members by Thomas Sully, Sir Thomas Lawrence, and Sir Joshua Reynolds, as well as a framed letter from George Washington to an ancestor, hung on the walls. Visitors to this house and its three hundred acres included such writers as Henry James, Matthew Arnold, and William Dean Howells; Owen Wister's mother, the quirky Sarah, inspired characters in Henry James's fiction (see Payne, 16-17). Young Owen's education was appropriate to his social class, including boarding school (fashionable St. Paul's in Concord, New Hampshire) and then as one of two Philadelphians in his Harvard class of 1882. Fanny Kemble's connections opened the doors of Bostonian society to Wister, where he observed the subtle differences between that city's most prominent citizens and those of his native Philadelphia. He also made a friend in Theodore Roosevelt (Harvard, Class of 1880). Throughout his life, Roosevelt wrote frequent and warm letters to "Dan" Wister, who visited Roosevelt both at the White House and at Sagamore Hill, Oyster Bay, New York. 10

A Phi Beta Kappa graduate in 1882 with first honors in music, Wister hoped for a musical career. Wister's physician father, however, wanted a more practical profession for his son. For two years the new Harvard graduate worked at the Boston Union Safe Deposit Vaults, where perched on a high stool below stairs he performed one of his principal duties: calculating, over and over, interest at two-and-a-half percent. Eventually Wister escaped theVaults, giving in to his father's insistence that he pursue a profession more "respectable" than music: Wister wrote his father that he would work for most of 1885 at the Philadelphia law office of Francis Rawle and then in the Fall enroll at Harvard Law School (see Roosevelt, 27-28). "He hated law," wrote Wister's cousin Alice, Lady Butler: "His father forced him into it."11 Another blow to his artistic aspirations came in May 1885. Wister then wrote to William Dean Howells to ask his opinion about a manuscript novel, co-authored with Wister's cousin Langdon Mitchell. These two hundred thousand words-about a young man who wanted to be a painter but was forced into business by his father-showed talent, Howells answered, but should "be never shown to a publisher" (Roosevelt, 23).

In June 1885, Owen Wister suffered a mental and physical collapse. No doubt his capitulation to his father's demands and his disappointment with Howells's assessment of his novel both played some part. Whatever the precise cause of Wister's illness, his neurasthenia was a common ailment of his social class. Such nineteenth-century writers as physician George M. Beard contended that nervous illness was an understandable reaction of the most sensitive and refined in America, especially those of Anglo-Saxon stock, to the pressures of modern life. As cultural historian Tom Lutz observes, "Beard expresses some typical late-Victorian fear of the possible degeneration of the handful of people who are the caretakers of a fragile civilization and argues that while those affected by the disease constitute a very small part of the culture as a whole, the rest of the population was as unrefined as it was healthy."12 Besides Beard, the other main contemporary theoretician of neurasthenia was Wister's cousin,the physician and novelist S. Weir Mitchell. Mitchell's frequent prescription was an enforced rest cure, a treatment horrifyingly documented by his patient Charlotte Perkins Gilman in her story "The Yellow Wall-paper." But some men who consulted Mitchell received advice about a temporary change to a more vigorous lifestyle. For Wister, his cousin prescribed a trip West for his health. Mitchell told the patrician Wister, "There are lots of humble folks in the fields you'd be the better for knowing."13 The rest is history-or the history of the "Western," that most ubiquitous of American cultural constructs.

Wister made extended trips to the West ten times between 1885 and 1895, at first to escape the boredom of those distasteful law studies at Harvard from 1885 to 1888. Within a week of his arrival at Medicine Bow, Wyoming, in 1885, he could write, "I'm beginning to be able to feel I'm something of an animal and not a stinking brain alone" (OWW, 32). "Fresh from Wyoming and its wild glories," in the autumn of 1891, Owen Wister and Walter Furness, son of the great Shakespearean scholar Horace Howard Furness, sat in the exquisitely paneled dining room at the exclusive Philadelphia Club and discussed the primitive West: "Why wasn't some Kipling saving the sage-brush for American literature?" After the oysters and the coffee and while drinking the excellent claret, Wister told his friend, "Walter, I'm going to try it myself! I'm going to start this minute." And so he did, going to the club's library and that night writing much of his first published Western story, "Hank's Woman."14 Many of the Western short stories that he wrote over the next decade were integrated with some new material and published in April 1902 as The Virginian; the book was dedicated to his friend Theodore Roosevelt (then serving as President). Almost immediately Wister became a famous man-and steadily more famous as The Virginian went through forty printings from April 1902 to October 1911.

No doubt to his publisher's dismay, Wister- desiring, he said, "to turn to other themes for a while, even if the box-office receipts should fall away"-followed up on one of the nation's all-time best-selling novels by writing a far different one about high-society manners in Charleston, South Carolina (Roosevelt, 245-46). Wister had, as he had discussed with Walter Furness at the Philadelphia Club, "saved the sage-brush for American literature," but he knew the actual old West was gone for good. As he wrote his mother, "The frontier has yielded to a merely commonplace society. . . . When I heard that Apache squaws now give their babies condensed milk, my sympathy for them chilled" (OWW, 210). He wrote other Western stories after The Virginian, but they increasingly eulogized what had been.

Thus Wister turned to the South, setting his narrative at the dawn of the twentieth century. A wedding cake (made from the "Lady Baltimore" recipe) is ordered for a Charleston wedding that never happens. John Mayrant, the bridegroom-to-be, is a wholly admirable representative of southern refinement. The supposed bride, Hortense Rieppe, is also a southerner, but she has allied herself with decadent, materialistic, unfeeling nouveaux riches of the North; those people are "the Replacers" of all that was once civilized and valuable in America. John Mayrant and Hortense Rieppe eventually find more appropriate spouses. Mayrant weds a woman combining modern sensibilities with Charleston gentility; Rieppe marries a reprehensible leader of "the yellow rich," surrounded by a bridal party "composed exclusively of Oil, Sugar, Beef, Steel, and Union Pacific" (Lady Baltimore, 385).

1. Donald E. Houghton, "Two Heroes in One: Reflections upon the Popularity of The Virginian," Journal of Popular Culture 4 (1970), 497; see also Payne, xii.

2. A small section (1,800 words) of Romney appeared in the Bulletin of the Philadelphia Museum of Art 35 (May 1940), 3-5.

3. Fanny Kemble Wister [Stokes], "Letters of Owen Wister, Author of The Virginian," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83 (1959), 3.

4. Thomas Wharton, "Bobbo" and Other Fancies, intro. by Owen Wister (New York: Harper & Bros., 1897), xiv.

5. Lincoln Steffens, "Philadelphia: Corrupt But Contented," McClure's Magazine 21 (July 1903), 249-63; this article was reprinted in Steffens's The Shame of the Cities (New York: McClure and Phillips, 1904).

6. Cornelius Weygandt, Philadelphia Folks: Ways and Institutions In and About the Quaker City (New York: Appleton-Century, 1938), 7.

7. Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen, 155.

8. This descent runs Dr. Edward Jones (1645-1727), Jonathan Jones (1680-1768), Owen Jones (1711-1793), Lowry Jones (b. 1742), Charles Jones Wis-ter (1782-1865), Dr. Owen Jones Wister (1825-1896), Owen Wister (1860-1938). On Edward Jones's and John ap Thomas's purchase of part of the "Welsh Tract" (now called the "Main Line"), see Charles H. Brownrigg, Welsh Settlement of Penn-sylvania (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1967), 45-78. Owen Wister set part of Romney on the "Main Line," calling the community there "Ap Thomas" after one of the co-purchasers of this land from William Penn.

9. Baltzell, Puritan Boston, 299.

10. Wister's father wanted his son to be christened Daniel, but the mother's choice of Owen (with no middle name) won out. "Dan," however, became Owen Wister's nickname.

11. As told to N. Orwin Rush; see his The Diversions of a Westerner (Amarillo, Texas: South Pass Press, 1979), 61.

12. American Nervousness, 1903: An Anecdotal History (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), 7-8.

13. OWP, Box 1, "Miscellaneous Items: At the Hot Springs," as quoted in Payne, 76.

14. This tale is here presented as Wister recounted it in his Roosevelt (29), published in the author's seventieth year. However, a few months before that Philadelphia Club meeting, on 20 June 1891, Wister wrote in his journal that he wanted to write of the West and in fact was then composing a story, "Chalkeye." What was finished of "Chalkeye" was posthumously published in American West, 21 (January- February 1984), 37-52.

© 2001 The Penn State University

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.