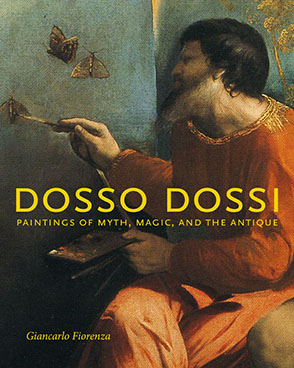

Dosso Dossi

Paintings of Myth, Magic, and the Antique

Giancarlo Fiorenza

“Giancarlo Fiorenza has provided an indispensable contribution to the study of Italian Renaissance culture. . . . There is, in fact, no comparable account of Ferrarese court culture in the sixteenth century.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Winner of a 2009 AAUP Book Jacket and Journal Show for Scholarly Illustrated

Dosso’s art challenges conventional iconographic analysis, and Fiorenza considers how the poetics governing his imagery recasts literary sources, including Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, by magnifying their most pictorial components. Perhaps more compellingly than any of his contemporaries, Dosso’s paintings transformed courtly ideals and princely identity into a new sensual spirit.

“Giancarlo Fiorenza has provided an indispensable contribution to the study of Italian Renaissance culture. . . . There is, in fact, no comparable account of Ferrarese court culture in the sixteenth century.”

“In this beautifully crafted, original study, Fiorenza not only renovates Dosso’s reputation in terms of his ‘luxuriant and festive manner,’ but also effectively situates his work within its northern Italian context.”

Giancarlo Fiorenza is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Design at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo. His articles have been included in such publications as Art Bulletin, Renaissance Quarterly, I Tatti Studies, and Modern Language Notes.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Dosso’s Courtly Maniera

The Nature of the Gods

Elysium

Priapic Painting

Enchanting Painting

Fables, Ruins, the bell’imperfetto

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction: Dosso’s Courtly Maniera

Any study of Giovanni di Nicolò Luteri (or de Lutero; c. 1486?–1542), known in the sixteenth century as Dosso, must address Giorgio Vasari’s vitriolic reproach of the artist, which was so persuasive that it has colored nearly every subsequent assessment of his work. Vasari’s infamous attack involves the commission to help decorate the Villa Imperiale at Pesaro for Duke Francesco Maria della Rovere and Duchess Eleanora Gonzaga. It appears that Dosso and his younger brother and assistant Battista worked at Pesaro sometime between 4 December 1529 and 10 September 1530, dates corresponding to the absence from their habitual employment at the court of Ferrara. In the 1550 edition of his Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, Vasari states that the brothers’ frescoes failed to impress the duke, who had them destroyed. In the 1568 edition, on the other hand, Vasari elaborated on this purported misadventure, turning it into a full-blown example of invidious presumption on the part of the artists, whose manner transgressed all boundaries of affectation:

At this same time Girolamo Genga, the painter and architect, was making for Duke Francesco Maria of Urbino many decorations in the Villa Imperiale above Pesaro, as will be related in the proper place. Among the painters hired to work there by Signor Francesco Maria were Dosso and Battista Ferrarese, summoned especially to do landscapes (paesi). In this palace many pictures had already been executed by Francesco di Mirozzo (sic for Francesco Menzocchi) of Forlì, Raffaellino dal Colle of Borgo Sansepolcro, and many others. Having arrived at the Palazzo Imperiale, Dosso and Battista Ferrarese, as it is the custom of certain men so made, criticized the greater part of the things that they saw and promised the duke that they wanted to do far better things. Now Genga, who was a shrewd person, seeing how the matter was likely to end, gave them a room of their own to paint. Thereupon, when setting themselves to work, they forced every labor and study in order to show off their virtù. But whatever may have been the reason, they never made, in all their lives, any work less praiseworthy, or rather, worse, than that one. It seems to happen often that, in the greatest of need and when the most is expected of them, men become bewildered and blinded in judgment, and perform worse than ever. This can also occur from their malign and evil nature of always criticizing the works of others, or from too much desire to force (sforzare) the ingegno. Letting things come naturally, just as nature offers, without however leaving behind study and diligence, seems a better method than wishing to draw from the ingegno, as it were by force, things that are not there. So it is also true that in the other arts, and especially in that of writing, all too well one recognizes affectation (affettazione), and also, so to speak, too much study (il troppo studio) in everything. Therefore, when the Dossi’s work was discovered to be of a ridiculous manner (maniera ridicola), they departed from the duke in disgrace; and he was forced to tear down all that they had done, making others do the repainting based on Genga’s design.

Considering the foregoing remarks, one may rightly question the value of devoting a book to Dosso, especially one on his secular paintings—works that are luxurious and arresting to be sure, but seemingly eccentric and almost purposely enigmatic according to conventional analysis. However, this episode appears to be an invention by Vasari, and one with a point. Art historians have long attributed to Dosso and Battista the frescoes at the Villa Imperiale that blanket the walls and ceiling of the Camera delle Cariatidi, which served as the prima camera, the room opening into the duke’s bedroom (fig. 1). Along the walls a series of caryatids transform themselves into verdant foliage, creating natural archways that open onto expansive vistas, culminating in a playful arbor in the ceiling. The imagery (heavily restored) accords with Vasari’s statement that the brothers had earned a reputation for representing landscapes (paesi), and it was for that specific skill that they were called to Pesaro. What is more, there is no evidence that the duke ordered any decorations by Dosso or Battista to be destroyed. While it would be easy to dismiss Vasari’s anecdote as a colorful fiction, this would overlook the didactic intent of the episode. It is also tenuous to claim, according to one recent assessment, that Vasari “had too serious an idea of painting to appreciate the charm, entertainment, and free flights of fantasy” of Dosso’s pictorial language. This explanation offers only a superficial look at Dosso’s art, disregarding the equally serious attention he gave to his own practice. The more difficult question concerns the underlying truth governing Vasari’s narrative. What did Vasari mean by criticizing Dosso’s art in terms of a “maniera ridicola,” and moreover, what does this reveal about Dosso’s own maniera?

From a literary perspective, Vasari’s biographies provide instructive examples of the ways and means of exercising virtue in the field of the figurative arts. He frequently employs hyperbole in order to inspire imitation of the pioneers of the modern or central Italian manner (maniera moderna): namely, Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo. It is therefore reasonable to situate Vasari’s attack on Dosso for harboring an affectation that is opposed to the elusive quality of grace (grazia) within the rhetorical genre of praise and blame. Affectation appears laborious and in turn calls attention to the artificiality of performance. In his Book of the Courtier, which espouses model courtly behavior through the form of a dialogue imaginatively set at Urbino in 1507, Baldesar Castiglione asserts that extravagant affectations, “because they exceed a limit, cause laughter rather than tedium.” Castiglione contrasts affectation to sprezzatura, or calculated spontaneity, whereby the courtier was enjoined to conceal the laborious social construction of his identity beneath an appearance of easy casualness. For the ideal courtier, he commends the ironic self-masking of artifice: “True art is what does not seem to be art; and the most important thing is to conceal it, because if it is revealed this discredits a man completely and ruins his reputation.” He furthermore compares affectation to the behavior of a painter who, not in control of his own diligence, does not know when to stop. This rhetorical commonplace goes back to Pliny the Elder, whose Natural History warns artists against the “evil effects of excessive diligence (nimia diligentia).” It is also significant that the Venetian art critic Paolo Pino writes in his Dialogo di pittura (1548) that all painting should be tempered by brevity lest artists introduce “all the makings of the world in one picture” (“tutte le fattura del mondo in un quadro”). By failing to comply with the rules of brevity, the painter risks producing works of art that were “disproportionate and clumsy” (sporzionato e goffo), moving the spectator to undesired laughter. Because artistic practice was intimately related to social etiquette, for Vasari, not only was the decoration by Dosso and Battista clumsy, but their attitudes breeched established modes of courtly behavior.

On a more personal level, Vasari’s criticism coincides with his ambivalence toward Emilian (or Lombard) artists in general, especially regarding their reluctance to embrace the maniera moderna. Consider the Ferrarese painter Benvenuto Tisi, called Garofalo (c. 1476 or 1481–1559), Dosso’s colleague and occasional collaborator. One reads in Vasari’s biography that Garofalo cursed his own Emilian manner after being stupefied at the works of Raphael and Michelangelo during his sojourn in Rome, where he longed to return. Garofalo adopted and updated a style of painting known as the maniera devota (devout manner), which was widely popular for displaying a sweetness of unified colors, soft atmospheric infusions, and expressive tender affections that inspired human devotion. The maniera devota was the uncomplimentary label Vasari attached to the dominant artistic style in and around Emilia-Romagna (especially Ferrara and Bologna) and Umbria, largely originating in the works of Francesco Francia, Pietro Perugino, Lorenzo Costa, and Boccaccio Boccaccino (Garofalo’s master) in the late fifteenth century. Vasari did not fail to point out how Michelangelo ridiculed the Bolognese Francia and the Ferrarese Costa as “two of the most solemn fools in art” (“due solennissimi goffi nell’arte”). Their followers, including Garofalo and Dosso, never fully abandoned the stylistic or affective dimensions of the maniera devota as Raphael himself had done when he settled in Rome. Perhaps the most relevant remark for understanding Vasari’s reception of Dosso’s art is his fatal blow to Francia. He relates that when the stolid Francia saw Raphael’s Santa Cecilia altarpiece on its arrival in Bologna, he realized the faults in his own style and literally dropped dead with envy. Vasari’s hyperbolic criticism of Francia’s “foolish presumption” (“stolta presunzione”) and his fable of Francia’s death—the artist, in fact, lived on—resonate in his criticism of Dosso’s invidious presumption and its disastrous artistic results.

As one of the earliest and most extended discussions of Dosso’s art, Vasari’s biography provides an excellent starting point from which to reexamine his pictorial vocabulary, which was conditioned by his Emilian roots. Vasari’s observations on Dosso’s career came on the heels of the criticism expressed by the Venetian art theorist Ludovico Dolce in his 1557 Dialogo della pittura intitolato L’Aretino. Dolce advocated the Venetian painter Titian (c. 1485/90–1576) as the paragon of painting, the one artist who, in his opinion, surpassed the excellence of Raphael and Michelangelo. When referring to the Ferrarese poet Ludovico Ariosto’s praise of Dosso and Battista in his famed romance epic Orlando Furioso, Dolce claims that the brothers were undeserving of such publicity and instead painted in a highly clumsy style: “e preferò una maniera in contraria tanto goffa.” However exaggerated and unsympathetic, what the accounts by Vasari and Dolce have in common is the recognition of Dosso’s distinctive style. They also point to the problem of reception and interpretation of Dosso’s art as a whole that continues to this day. Some of the most common epithets attached to the artist’s works in modern studies include “undisciplined,” “aberrant,” “caricatured,” “romantic,” “anticlassical,” “grotesque,” and “intellectually resistant.”

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.