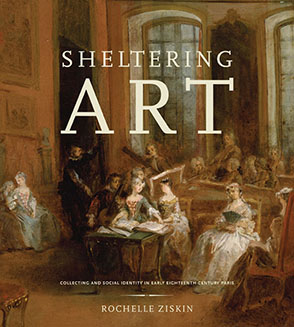

Sheltering Art

Collecting and Social Identity in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris

Rochelle Ziskin

“Rochelle Ziskin’s learned study brings to vibrant life the extensive social and political networks out of which two major early eighteenth-century Parisian art collections grew, and it reveals how the practices that built each collection were decisively shaped by the ideals of these overlapping networks—as well as by the conflicts that sometimes divided them. In this way, Ziskin elegantly enriches our understanding of what was at stake in the subtle distinctions that characterized the varieties of contemporary elite taste, and she significantly enlarges our knowledge of the intricate cultural politics of Louis XV’s Regency.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Rochelle Ziskin’s learned study brings to vibrant life the extensive social and political networks out of which two major early eighteenth-century Parisian art collections grew, and it reveals how the practices that built each collection were decisively shaped by the ideals of these overlapping networks—as well as by the conflicts that sometimes divided them. In this way, Ziskin elegantly enriches our understanding of what was at stake in the subtle distinctions that characterized the varieties of contemporary elite taste, and she significantly enlarges our knowledge of the intricate cultural politics of Louis XV’s Regency.”

“In her extraordinary new study of collecting, Rochelle Ziskin deftly explores the moment when leadership in taste migrated from the court of Louis XIV to newly fashionable Paris. She persuasively argues that two rival circles competed, endowing collectibles with distinct social meanings. Ziskin’s examination is developed in greatest depth and subtlety when she treats the houses of the leaders of each group, Pierre Crozat and the comtesse de Verrue. While Crozat established a circle of erudite art connoisseurs, Verrue created a sanctuary for art lovers. In assessing the significance of these social practices, Ziskin turns to the social codes embedded in collections and the public and private uses of the spaces that showcased them, and she examines the relationships between collecting, contemporary art criticism, and the literary Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns. She assesses the importance of the regent and his collections at the Palais-Royal and draws new conclusions about the roles played by contemporary artists—especially Watteau and Rosalba Carriera but also Claude Audran, Charles de La Fosse, the Boullogne brothers, the Coypels, and the architects Cartaud and Oppenord. Blending original research carried out in Paris, Stockholm, Turin, London, Munich, and Monaco with new questions regarding the ideological foundations of social and gender constructions, she has written an original work of high quality that will, like her book on the Place Vendôme, have a substantial impact on the field.”

“Rochelle Ziskin brings to life the world of art collecting and its role in defining political and personal allegiances in early eighteenth-century Paris. With rich details mined from archival research, Ziskin reconstructs the collections of prominent Parisian art collectors—including those of Pierre Crozat, the comtesse de Verrue, Philippe II d’Orléans, and Jean de Jullienne. Further, she includes much previously unpublished information on the provenance of artworks and on the configuration and function of particular architectural spaces. As she offers an intimate glimpse into the lives of these collectors and their households, Ziskin also connects their collecting patterns to larger cultural and political transformations. Sheltering Art is lucidly written and well illustrated and is an important contribution to our understanding of the dynamics of collecting, identity, and ideology during this period.”

“Rochelle Ziskin provides a much-needed study of private collecting in Paris in the first two decades of the eighteenth century, and of the domestic settings and ways in which the works of art were displayed in the interiors. Sheltering Art is not only a history of collecting; it also gives insight into the role that private collections played for major artists thirty years before the public display of the Royal Collection at the Luxembourg Palace in 1750 and the emergence of the public museum at the end of the century.”

“This impressive work of scholarship examines the origins of collecting in Paris at the start of the 18th century. Ziskin outlines the new social and political spheres that characterised the period, and the shift away from the King’s court as the nexus of cultural life. Two rival circles of art collectors emerged as the century progressed, and Ziskin’s ambitious study explores their ideologies and motivations, as well as the nature of their collections.”

“Rochelle Ziskin’s Sheltering Art: Collecting and Social Identity in Early Eighteenth-Century France is a tour de force of scholarship, exhaustively researched and lucidly presented. Not surprising for this scholar, she has written an admirable book comprising larger historical narratives and theoretical frameworks, but full of fascinating details, drilling down through the layers of family histories, amorous entanglements, webs of friendship, and political alliances. . . . Impressive in its scope and depth, Ziskin’s book is a must-read.”

Rochelle Ziskin is Professor of Art History at the University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Introduction

1 Cultural Geography of the French Capital Circa 1700

2 Cloistered in the Faubourg Saint-Germain

3 The Maison Crozat Transformed

4 A Circle of “Moderns”

5 The Regent and Collecting on the Right Bank

6 Les Anciens and an Expanding Public Realm in the Arts

7 The Circles Converge: Carignan and Jullienne

Conclusion

Note on the Appendixes

Appendixes

1 Maison Crozat, rue de Richelieu, in 1740

2 Hôtel de Verrue, rue du Cherche-Midi, end of 1736

3 Collections of Lériget de La Faye, Glucq de Saint-Port, and Lassay

4 Collections of Nocé and Fonspertuis

5 Hôtel de Morville, rue Plâtrière, in 1732

6 Selections from the Collection of Carignan

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction

The turn of the eighteenth century was a time of transition in France, when new concepts of modernity emerged in virtually every cultural realm. This renewal was sparked by a sharp decline in the royal patronage that had so monopolized artistic life during the late seventeenth century. Already in the 1690s, and to a greater extent after 1701, as the late wars of the reign of Louis XIV drained the treasury and news of military reversals weighed heavily upon court life, the highest-ranking nobles sought to escape Versailles. Increasingly they spent time at alternate courts, including those of the grand dauphin at Meudon and the duchesse du Maine at Sceaux.

During the first decade of the new century, the court society of Louis XIV yielded to a less hierarchical and more richly diverse social and cultural life in Paris. Courtiers and high-ranking nobles began building new private residences in the capital, mostly in the newly fashionable faubourg Saint-Germain in the southwest sector, with its large unencumbered parcels. On the Right Bank, building activity accelerated among the financial families, who were profiting handsomely from wartime finance. They tended to cluster near the controller general of finance, in the western district between the two new royal squares—the Place des Victoires and the Place de Louis-le-Grand (Vendôme) (see figs. 1–2). The boom in elite residential building in the capital meant employment for architects, decorative artists, and a range of artisans associated with the building trades. It also had crucial ramifications for painters, who now turned to private patrons and the art market.

Paris became, once again, the social and cultural center of France. As the capital reclaimed its prominence, no single center replaced Versailles; instead, cultural life became more diverse and more vibrant. No longer could the royal court dictate fashions in the arts. When the government officially returned to Paris after the death of Louis XIV in September 1715, even the Palais-Royal, the seat of the regent, had no monopoly on cultural life in the capital. The regent’s aversion to the routines of court life continued even after the court returned to Paris. He preferred to separate his public responsibilities from his cultural patronage and private life. With discipline relaxed and power more decentralized, rival centers of culture competed for preeminence.

This book is a study of one of the most significant aspects of the newly decentralized and reenergized artistic culture of Paris—the rise of a new generation of collectors, the houses they conceived to harbor their treasures, and the cultural sphere that flourished within them. As the role of the Crown and its underfunded academies diminished, leading art collectors emerged to fill the void in the visual arts. At a time when there were no art museums and many of the Crown’s most important paintings had been removed to Versailles, private collections were an essential resource for artists grappling with changes in clientele and the marketplace.

Art collections formed a primary component of all of the houses in this study. They largely established the character of the domestic realm they adorned, and they functioned as a key medium of social representation. Although portable and more or less easily rearranged, collected objects regularly generated new spaces and sometimes distinctive decorative programs to accompany them, as collectors built or transformed their dwellings to provide settings for their assembled art objects. During the course of the century, as collecting became an increasingly widespread activity among Parisian elites, the impact of this class of very special dwellings grew. Planning strategies and decorative embellishments—some introduced to enhance the presentation of collections—would have broader repercussions in the realm of domestic architecture. Several houses discussed here were widely admired and had an impact on the conception and evolution of French domestic design. Especially important was the pair at the center of this study—the Maison Crozat and the Hôtel de Verrue.

A number of important art collectors populated the Parisian cultural sphere during the first half of the century, and the most prominent among them appear in this volume. However, I focus here on those collectors associated with two leading (and rival) groups. My aim is to reveal how contests among art collectors were embedded within larger conflicts in cultural, social, and political life and to trace the ways in which collections helped forge social identities.

At the centers of those competing circles were the two most prominent private collectors of the period, Pierre Crozat and the comtesse de Verrue. Crozat (1665–1740), the son of a provincial banker and younger brother of one of the most powerful financiers of the époque, was second only to the regent in the renown of his collection of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian paintings and unmatched in the importance of his assembled drawings—especially those of old masters. Jeanne-Baptiste d’Albert de Luynes (1670–1736), the comtesse de Verrue, may be best known today as Alexandre Dumas’s fictive dame de volupté, a sobriquet she reputedly created and one that has too easily obscured her crucial role in the art world of early eighteenth-century Paris. She had the social confidence to renounce the traditional pattern of collecting that Crozat had eagerly embraced and turned from “serious” Italian paintings to “petits sujets,” bucolic landscapes, and amorous mythologies, primarily by painters of the Northern and French schools. Like Crozat, she shaped a remarkable and widely admired dwelling that was central to her identity and famous during her lifetime. The importance of each house was enhanced by the way it functioned. Each became a key site of artistic discourse, a place where art lovers and artists assembled, and a locus for assessing competing systems of value, where distinctive outlooks were forged, defined, and absorbed.

The significance of Crozat’s patronage is now widely accepted, but Verrue and the members of her circle have been less well studied. As recently as 1994 Antoine Schnapper, the distinguished scholar of seventeenth-century French collecting, reflected upon lacunae in our knowledge of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century collectors, lamenting that “we can neither identify nor place on the social scale the dame de qualité of the rue du Cherche-Midi, who, according to Germain Brice, had a collection of medals, sculpted gems, and paintings of great masters.” That dame de qualité was, in fact, the comtesse de Verrue. Since Schnapper’s study, a handful of scholars have helped Verrue emerge from the relative obscurity into which she had fallen, but the contents of her collections, the manner in which they filled her house, and the social meanings they embodied all require closer scrutiny. Also poorly understood are the interactions between the dwellings and collections of most of those who constituted her closest coterie, yet their houses form an essential context for comprehending Verrue’s practices.

The rival circles that assembled around Crozat and Verrue were closely linked to different social and political factions. Norbert Elias’s influential model of court society, which stressed competition for preeminence among social estates and ranks within them, has recently been challenged by a growing chorus of critics who find that it inadequately accounts for the role played by faction. Political factions were not socially monolithic, and each had satellites that extended beyond the court to the capital. Following the death of Louis XIV, three principal princely clans—the Orléans (fils de France) and the Condé and Conti (princes du sang)—competed for preeminence in Paris. Sometimes their interests aligned, most notably when they joined forces to annul the testament of Louis XIV, which greatly enhanced the power and prestige of his legitimated sons; more often, however, competition prevailed, and it affected every representational realm, including art patronage and collecting.

What has been characterized as simple differences in taste among collectors camouflages not only competing factions but also rival ideologies that endowed houses and assembled art objects with larger social meanings. Although the groups of collectors explored in this study were socially mixed, like the political factions with which they were affiliated, they had distinctly different outlooks. In Verrue’s coterie, an aristocratic ideology prevailed, even if some of its members had emerged from bourgeois milieux. Crozat’s erudite fraternity was predominantly bourgeois, despite the presence of some men of noble birth. Members of each group absorbed its prevailing outlook to different degrees. The regent was more closely associated with Crozat—who acted as his agent for acquiring paintings in France and Italy—but most often stood apart from, and above, these contests.

All of the collections in this study were more than the sums of their components. Each encompassed an “imaginary” realm—what Krzysztof Pomian has called the “invisible.” Where works were displayed, how they were installed, how they were used, how they were discussed: all of these aspects of collecting provide clues needed to reconstruct the imaginary sphere evoked by art objects and the social meanings that adhered to them and their settings. Paintings and other collected objects could bear values and signify allegiances far removed from the contexts and purposes for which they had been produced.

During the course of the century, patina—long effective in signifying distinguished lineage and devaluing newness—was largely superseded by fashion. Verrue and her intimates would not have prevailed in their use of collecting to bolster claims to higher status had the traditional value of patina endured. In contesting the social and cultural claims of men of new wealth like Crozat, fashion became extraordinarily effective as a medium of distinction.

The outcome of this competition would appear in the marketplace. Shifts in market values assigned to works of Italian, Northern, and contemporary French schools have been well established by scholars, but the ideological underpinnings of these shifting values remain to be explored. Market values illuminate the changing fortunes of these divergent camps, but they do not suffice to explain the many social meanings that became affixed to different types of art objects or how those meanings evolved over time. More relevant in charting the complex symbolic values borne by certain objects are insights that emerge from the anthropological literature on the gift. Several collectors in this study—especially Verrue and Crozat—crafted strategies to remove select objects from expected circuits of familial inheritance and the vagaries of the market. Those objects, conceived as personal legacies, garnered special significance and embodied disparate yearnings. They bound the giver and the receiver (actual or intended), remained symbolically linked to both, and could be used to demarcate a circle’s boundaries.

Although I stress rivalries between groups competing for preeminence, I do not mean to imply that there were no relations between those associated with different camps, nor that every collector joined one of these circles. I certainly would not argue that their collecting patterns had nothing in common. In the pages that follow, readers will find evidence of loans and exchanges of paintings that occasionally crossed these barriers, dual alliances, and even a marriage in 1722 linking Crozat’s eldest nephew with Verrue’s niece. Nonetheless, despite inevitable points of contact, the two circles remained strikingly—and significantly—separate.

Their divergence is evident in the relationship of each coterie to the most brilliant painter of the period, Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), whose extraordinary talent was appreciated by collectors associated with both groups. Crozat—who invariably appears in art-historical accounts of Watteau—lodged the painter for a time and opened his portfolios to him, but the results of his patronage were some of Watteau’s most derivative and atypical paintings. Collectors in Verrue’s circle, however, eagerly sought the artist’s most innovative works and almost certainly gave him access to prime examples of the Northern paintings that served as important sources for his personal idiom.

As we shall see, these groups would define themselves, to a large degree, vis-à-vis one another. It was precisely through difference that their collections came to be endowed with social meanings that were resonant to, and understood by, contemporaries in Paris during the first half of the eighteenth century.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.