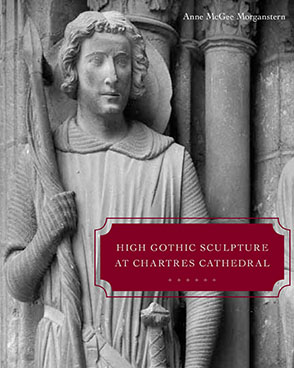

High Gothic Sculpture at Chartres Cathedral, the Tomb of the Count of Joigny, and the Master of the Warrior Saints

Anne McGee Morganstern

High Gothic Sculpture at Chartres Cathedral, the Tomb of the Count of Joigny, and the Master of the Warrior Saints

Anne McGee Morganstern

“Anne McGee Morganstern's new book reconstructs the history of the tomb of Count Guillaume de Joigny in an impressively meticulous fashion. It is a genuine and significant addition to the literature.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Anne McGee Morganstern's new book reconstructs the history of the tomb of Count Guillaume de Joigny in an impressively meticulous fashion. It is a genuine and significant addition to the literature.”

“In her thoughtful and thorough High Gothic Sculpture at Chartres Cathedral, the Tomb of the Count of Joigny, and the Master of the Warrior Saints, Anne McGee Morganstern reassesses the much-studied sculpture of the Chartres south transept through innovative comparisons with the tomb sculpture of Count Guillaume de Joigny. These investigations clarify the nature of the sculptural workshop during the thirteenth century, an issue of vital importance to all who study medieval art. Additionally, she revitalizes the method of stylistic analysis in a way that is useful to twenty-first-century readers. This book is a significant contribution to the study of Gothic sculpture.”

Anne McGee Morganstern is Professor Emerita of the History of Art at Ohio State University. She is the author of Gothic Tombs of Kinship in France, the Low Countries, and England (Penn State, 1999).

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 The Tomb of Count Guillaume I in the Priory of Notre-Dame in Joigny

2 Beyond the Tomb: Implications of a Stylistic Analysis of the Count’s Tomb

3 The Context of the Porches of Chartres Cathedral

4 The South Transept Porch of Chartres Cathedral

5 The North Transept Porch of Chartres Cathedral

6 The Coronation Portal at Longpont-sur-Orge

Conclusion

Appendix 1 An Iconographic Conundrum: Saint Theodore and Saint George

Appendix 2 The Iconography of the South Transept Porch

Appendix 3 The Iconography of the North Transept Porch

List of Abbreviations

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction

I did not set out to write a monograph on a medieval sculptor. The project began when I was shown a beautiful effigy carved in high relief on a tomb slab in the dark side-aisle of a small church in Joigny. When first contemplating the introduction of the tomb to an audience beyond the small community where it originated, I thought to continue my earlier preoccupation with tombs as by-products of society and its rituals.1 But after I realized the tomb’s link to major sculpture at Chartres Cathedral, the implications of this connection for the chronology and development of Gothic sculpture in France seemed more important to me than writing another contribution to art as cultural history, however rewarding that might have been. Therefore, I have chosen to write what might be considered an old-fashioned book, one in which formal analysis is combined with documentation to bring new evidence to an old debate. In writing an essay in which stylistic analysis is the fulcrum on which my chronological argument and the further traces of a single master’s activity depend, I am continuing the tradition of the great connoisseurs who have been responsible for forming the recognition of Gothic art as a phenomenon in the history of European art: Wilhelm Vöge, Louis Grodecki, and Willibald Sauerländer, to name only a few of those dealing with sculpture and stained glass.2 For them, stylistic analysis has been a tool for isolating the creative minds and skilled hands that were responsible for the new directions in which the art that we call Gothic evolved. This concern with innovative masters was certainly conditioned by the subsequent development of the autonomous artist in European art, but it is not the same as the notion of style and its analysis as an end in itself.3 Nor can the connoisseurs of Gothic sculpture be blamed for the occasional deterioration of stylistic criticism into a parlor game for art dealers and museum curators motivated mainly by market values and personal ambition. Rather, for the scholar endeavoring to write history, stylistic analysis is an indispensable tool, especially in areas in which there is little or no documentation.4 When accurate stylistic analysis can be combined with pertinent documents, the art historian has a foundation from which to project an account of the circumstances in which a work of art was created. This was the rare opportunity that seemed to be offered by the tomb in Joigny, and my essay is an attempt to write a convincing narrative that combines stylistic analysis with relevant documentation in order to elucidate a crucial period in the decoration of Chartres Cathedral.

From the beginning it should be realized that the crux of my argument is the attribution of the tomb at Joigny to the sculptor of the warrior saints at Chartres and that the chronological implications of this attribution rest on the accurate identification of the effigy on the tomb as William I, count of Joigny. Therefore, in chapter 1, I identify the tomb’s occupant and treat the somewhat complicated history of the tomb, which was sequestered during the French Revolution to save it from destruction and subsequently returned to its original venue, but in an altered state and with an uncertain identity. Chapter 2 reveals the stylistic proximity of the tomb’s effigy and the warrior saints at the Portal of the Martyrs on the south transept of Chartres Cathedral and other sculpture at Chartres. Chapter 3 outlines the context of the warrior saints and discusses the chronology of the cathedral’s rebuilding after the fire of 1194, including the transept portals.

The porch of the south transept is treated in chapter 4, which opens with a review of the evidence for dating the completion of the porch by 1224, including the probable date for the tomb of the count of Joigny. In a detailed examination of the porch sculpture, two master sculptors emerge, the more important being the Master of the Warrior Saints, who appears to have furnished models for most of the other sculpture. At the end of the chapter, the documentation relevant to the division of work at the site is weighed.

The firm date for the south porch argued in chapter 4 provides a basis for considering the unsettled chronology of the north porch in chapter 5. A review of previous scholarship on the diverse styles displayed by the sculpture of the north porch precedes a revised sequence of work based on stylistic analysis, building logic, and the chronology of related sites. Analysis of this sculpture detected the style of the Master of the Warrior Saints in the voussoirs of one of the framing arches, suggesting that he played a minor role in furnishing designs for the porch. Chapter 6 deals with the master’s role in creating a small portal for the Benedictine monastery at Longpont-sur-Orge, revealing his dependence on both Paris and Chartres. The conclusion highlights the contribution of my study and considers the new place of the Master of the Warrior Saints in the history of Gothic sculpture.

Three appendixes supplement the text by providing a discussion of the identity of the warrior saint at Chartres traditionally known as Saint Theodore (appendix 1) and reviews of the iconography of the porches (appendixes 2 and 3).

The potential of using tomb sculpture to resolve some of the intractable chronological problems posed by the construction of the great French cathedrals remains largely unexplored, although I am not the first to notice the relationship between sepulchral and cathedral sculpture: in a short pioneering article published in 1964, Willibald Sauerländer attributed seven tombs in the abbey of Notre-Dame-de-Josaphat at Lèves to carvers of some of the transept sculpture of Chartres Cathedral.5 By 1970, he had identified additional monumental tombs related to thirteenth-century architectural sculpture: the retrospective memorials for King Clovis I and King Childebert in Paris, and those for the ancestors of Saint Louis in Saint-Denis.6 And, more recently, I attributed the major part of the thirteenth-century tomb of Adélais de Nevers at Joigny to a sculptor from the cathedral lodge of Notre-Dame in Paris.7

Such evidence suggests that until the fourteenth century, when the demand for fine tombs in marble or alabaster at the French court fostered the evolution of the specialized tomb-maker (tombier), discerning patrons sought carvers in the masons’ lodges when they wished to commission a funerary monument.8 This practice extended well into the fourteenth century in the south of France and Spain as well as at Chartres, as indicated by a payment in 1369 to a stonecutter/mason (lathomus) and tomb-maker (fabricator tumulorum) for the tomb of Godfrey Faber, a canon at the cathedral.9 The headmaster at both Narbonne and Gerona Cathedrals in the early fourteenth century, Jacques de Fauran, signed a contract for the tomb of Guillaume de Vilamari, bishop of Gerona, in 1322, although it is unclear whether he had a hand in the execution of the tomb aside from the columns and capitals stipulated in the contract.10 And as late as the fifteenth century, the exceptionally versatile Jacques Morel was, by turns, silversmith, headmaster, and tomb-maker.11

The extension of the master sculptor’s purview to monumental tombs allows us to imagine his working more independently than in the large workshop at a major cathedral site, probably aided in most cases by an assistant and engaged in projects of limited scope that were expected to be seen at close range. In view of these circumstances, a commission for a tomb could extend a sculptor’s potential and alter his production somewhat, as the present study suggests. However, beyond that, a major benefit of studying Gothic tombs lies in their potential for dating the sculptural decoration of the great cathedrals. As demonstrated in the present study, when tombs can be dated by the circumstances in which they were created, they furnish invaluable anchors for tracing the development of coeval sculpture.

The study of French medieval tombs is hampered by the disruption and destruction of the monasteries and their tombs during the Revolution. Even in the rare instances where sites and monuments remain, they have been altered, and reconstructing their history is a difficult process. But now and then, there is enough evidence to draw neglected monuments out of obscurity and into the light of history. The first part of the present study concerns such circumstances. Their unraveling has been complicated, involving research in archival and antiquarian sources to establish the origin of the tomb at Joigny and to track its vicissitudes during and after the French Revolution. But the effort has been worth the trouble involved. Now reconstituted and identified, a virtually unknown monument can be added to the corpus of French High Gothic sculpture. As outlined above, this monument provides a precious chronological indicator for the construction of the transept porches of Chartres Cathedral and the carving of their sculpture. And redating the south transept porch implies that the Master of the Warrior Saints was the artist responsible for introducing to Chartres the new forceful style that we know as High Gothic.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.