The Wake of Iconoclasm

Painting the Church in the Dutch Republic

Angela Vanhaelen

“Seventeenth-century Dutch church paintings have been the subject of much art-historical inquiry, and this handsomely produced volume makes a valuable contribution to the discussion. . . . Vanhaelen, a recognized specialist in this area, explores the connection between church paintings and contemporary religious thought—not just Calvinism, but also Roman Catholicism and even Islam. She brings out the significance of the works’ beautiful whitewashed walls; graffiti on those walls; the power of the word and the book; the political overtones of the invasion by Louis XIV and the reconsecration of the Utrecht cathedral; and the implications of the common theme of the open grave in church floors, among much else. The book includes over 50 fine illustrations (most in color), excellent footnotes, and a full bibliography.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

The Wake of Iconoclasm: Painting the Church in the Dutch Republic is the winner of the 2013 Roland H. Bainton Book Prize awarded by the international Sixteenth Century Society and Conference for the best book written in English dealing with Art and Music History within the time frame of 1450-1660.

“Seventeenth-century Dutch church paintings have been the subject of much art-historical inquiry, and this handsomely produced volume makes a valuable contribution to the discussion. . . . Vanhaelen, a recognized specialist in this area, explores the connection between church paintings and contemporary religious thought—not just Calvinism, but also Roman Catholicism and even Islam. She brings out the significance of the works’ beautiful whitewashed walls; graffiti on those walls; the power of the word and the book; the political overtones of the invasion by Louis XIV and the reconsecration of the Utrecht cathedral; and the implications of the common theme of the open grave in church floors, among much else. The book includes over 50 fine illustrations (most in color), excellent footnotes, and a full bibliography.”

“The Wake of Iconoclasm: Painting the Church in the Dutch Republic . . . tacks a high-stakes course for the pictorial repercussions of iconoclasm: in place of the triumphant confidence, joy, even pink-cheeked bluster we have come to expect of Dutch art, Vanhaelen gives us a church interior–based realism founded on the volatile ambivalence of an age of anxiety beneath the sunny veneer of convivial charm.”

“[Vanhaelen] intensively and insightfully investigates the interstice between the past and present faiths and art. . . . The book is amply illustrated, with most of the key paintings reproduced in color, some accompanied by exquisite full-page color details. Some of the included illustrations are rarely reproduced in the earlier literature, particularly in such high quality.”

“This book is a significant contribution to the field of Dutch art and religious culture. Angela Vanhaelen looks closely and with fresh eyes at the images of Dutch church interiors, and with the close observation of each detail, their architectural spaces and church-attending inhabitants come alive to the reader.”

Angela Vanhaelen is Associate Professor of Art History at McGill University.

Contents

Acknowledgments

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Part 1: Painting the Church

1 Time-Stained Walls

2 The Forbidden Image

Part 2: The Transformation of Public Space

3 The Contradictions of Church

4 Monumental Space: Reforming the Body Politic

Part 3: The Work of Mourning

5 Unresolved Histories

6 Death and Dutch Art

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Inside the [Amsterdam] Old Church, all that is left of the Gothic style is the high, bare, white walls, the columns, the vaulting, and the windows. There is not a single image on the walls, not a single piece of statuary anywhere. The church is as empty as a gymnasium. . . .

The chairs and stalls seem to have been placed there without the slightest concern for the shape of the walls or position of the columns, as if wishing to express their indifference to or disdain for Gothic architecture. Centuries ago Calvinist faith turned the cathedral into a hangar, its only function being to keep the prayers of the faithful safe from rain and snow.

Franz was fascinated by it: the Grand March of History had passed through this gigantic hall!

—Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1984

Realism’s History: Painting the Reformed Church

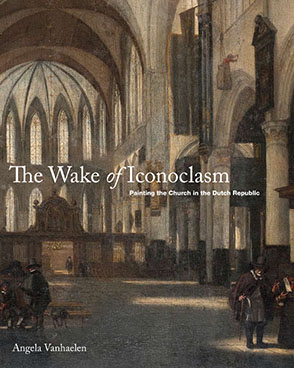

“Nowhere in Europe,” the art historian P. T. A. Swillens asserts, “has the church interior been the object of so much interest as in the Netherlands.” Building on this suggestive remark, The Wake of Iconoclasm focuses on a group of peculiar paintings: the numerous depictions of austere Calvinist church interiors that proliferated in the seventeenth century. It takes its departure from a seeming paradox at the heart of the Dutch Republic: why would so determinedly visual a culture be so fascinated by empty, bare churches? Responding viscerally to such absence, Kundera’s character Franz, a political idealist, proffers one answer. For him, the cleansed Gothic church is an image of liberation, making visible how “the Grand March of History had passed through this gigantic hall!” His is a view of history as a revolutionary process that sweeps away encumbrances of the past, clearing space for a happier future: “The Grand March is the splendid march on the road to brotherhood, equality, justice, happiness; it goes on and on, obstacles notwithstanding.” For Franz, emptiness manifests the progressive movement of history itself. But what he does not see—and does not regret, as his companion Sabina does—are the costs of progress, the destruction of much that was worthy. Sabina’s response runs counter to such a celebration of history. She experiences the Old Church instead as a space forged out of “a hatred of beauty,” evidence above all of the iconoclastic obliteration of past artistic traditions.

The divergent reactions of these fictional characters suggest a central concern of this book: the ambivalent understandings of history that the hollowed-out churches potentially evoked. This ambivalence is not visible only at the remove of three centuries, for European contemporaries, too, registered their disconcert and puzzlement when confronted with these vacant buildings. In the summer of 1663, Balthasar de Monconys, councilor to the king of France, toured the Dutch Republic. Art lover and connoisseur, he especially sought out curiosity cabinets, collections, and workshops, recording in a travel journal his most notable aesthetic encounters. At Rotterdam, a fellow curieux took him to visit the workshop of Anthonie de Lorme, a painter who specialized in interior views of churches. Monconys laconically notes that the painter “made nothing but the Church of Rotterdam, in diverse views.” He acknowledges nonetheless how attractive these works were: “but he did them well.” Such well-crafted paintings were desirable to the art collector, and he haggled with De Lorme about prices. After these dealings, Monconys and his companion moved on to see the paintings’ (unexciting) prototype: “from there we went to the Great Church, where there is nothing to consider, it is big enough and completely whitewashed on the inside.” The space that fascinates Kundera’s Franz does not stir Monconys. While De Lorme’s pictorial renderings of the church attract the admiration of this discerning connoisseur, he dispassionately dismisses the interior itself precisely because of its pronounced lack of visual interest.

Turning to one of De Lorme’s paintings (fig. 1), we can understand why Rotterdam’s main church might leave the art lover cold. The Interior of the Laurenskerk of Rotterdam meticulously depicts what Monconys described: a large, empty space “big enough and completely whitewashed on the inside,” punctuated only by funeral hatchments hanging on various columns. For a Frenchman traveling through England, the Dutch Republic, Germany, and Italy, this kind of Gothic interior could only disappoint. In other European churches, after all, a connoisseur’s discriminating eye could enjoy a variety of artistic masterpieces; these sacral spaces were akin to the collector’s cabinet. Architectural painters in the southern Netherlands often highlighted this aspect (fig. 2). In Peeter Neefs the Elder’s painting of Antwerp’s Roman Catholic cathedral, for instance, the nave resembles a gallery of painting and sculpture, the place of worship doubling as an exhibition space for sacred images, artfully made.

And yet De Lorme, we note with some astonishment, could build an international reputation painting nothing but diverse views of Rotterdam’s empty Laurenskerk; and there were about fourteen other seventeenth-century Dutch artists who made a specialty of austere church interiors. Despite Monconys’s dismissal of the Great Church, then, the large number of visual representations of what initially may seem like a rather limited subject indicates widespread interest in Reformed churches and their open, unadorned spaces. This engagement calls for explanation.

We might begin by contrasting De Lorme’s work to the earlier Flemish tradition (figs. 1 and 2). The Dutch painter clearly takes the genre of church interior painting in a new direction, provoking awareness of the changed relations between church and art in a Calvinist milieu. Another work, the captivatingly realistic View of the Laurenskerk of Rotterdam (fig. 3), illuminates a new state of affairs. This church is not without adornment. Bibles and Psalters lie ready for use on ledges of church pews; an enormous Ten Commandments board decorates the choir screen, vying for prominence with the elaborate text-inscribed guild board beside it. In contrast to the art-filled interiors of Antwerp painters, this is an emphatically text-filled space. While Neefs’s composition is structured by a high, straight perspectival view down the nave to the sacral center of the choir, De Lorme lowers and shifts perspective, focusing instead on the looming pulpit to the right. Embellished with a sizable soundboard and references to a Bible verse, this center of the Reformed worship service dominates the scene. The Gothic Laurenskerk—or Great Church, as the Calvinists renamed it—was formerly a Roman Catholic building, decorated much like the cathedral of Antwerp. Here it has been transformed by the Calvinists: in lieu of visual images, we see the Word.

In a long process of alteration, Gothic churches were stripped of sacred imagery both in acts of sudden ferocity and with unhurried deliberation during and long after the iconoclast riots of the late sixteenth century. Iconoclasm stormed through the Low Countries in the summer of 1566, beginning in the southern Netherlands and moving in waves up to the north. As news of violence spread, Calvinists were emboldened forcibly to enter and attack buildings that stood at the heart of their towns. Such furious acts were an opening volley in the Dutch Revolt against their Roman Catholic king, Philip II of Spain—a decisive turning point in Dutch history. An unusual church interior by Dutch artist Dirck van Delen depicts the iconoclastic fury, or beeldenstorm (fig. 4). A remarkable image, this is the only known painting of Dutch iconoclasm, created almost sixty years after the fact. The contrast between Neefs’s and De Lorme’s churches is striking, and Van Delen’s painting shows us how this radical transformation came about. It represents an imaginary Gothic interior—an “any church”—that is being purged of the artistic attributes of the Catholic faith. Iconoclasts, some brandishing tools as weapons, run into the building, scrambling over tombs, pulling down and breaking statues, paintings, a crucifix, and a funerary monument. Mouth agape, a monk peers from behind a column at the left. Below him, a brightly dressed turbaned figure strides into the church, either to witness or to participate in this violence against images. Visual cues, these representatives of Catholicism and Islam situate Calvinist iconoclasm within the larger context of contentious religious debates about the uses of imagery in worship. As a work of art that pictures the destruction of works of art, Van Delen’s painting is both a retrospective and an introspective image, a visual contemplation about the history of the image wars.

A prominent strand of art-historical criticism interprets the Dutch turn to descriptive realism as consequent upon iconoclasm’s stormy passage through the churches. From this perspective, Kundera’s fictional narrative resonates with G. W. F. Hegel’s extremely influential lectures on Dutch painting:

To frame a complete judgement on this last phase in our consideration of painting’s history, we must . . . visualize again the national situation in which it had its origin. What was responsible here was movement away from the Catholic Church, and its outlook and sort of piety, to joy in the world as such, to natural objects and their detailed appearance. . . . The Reformation was completely accepted in Holland; the Dutch had become Protestants and had overcome the Spanish despotism of church and crown. . . . This sensitive and artistically endowed people wishes now in painting too to delight in this existence.

Franz’s characterization of the Old Church in particular echoes Hegel’s assertion that the Dutch people had liberated themselves from the double tyranny of Roman Catholicism and Spanish monarchism. Turning away from tumultuous events of the immediate past, they became a people of the here and now. After reforming the church, they reinvented themselves, ushering in a new freedom and finally attaining “the superabundant sense of the joys of ordinary existence.” For Hegel, Dutch art expressed liberty and happiness in the everyday life and surroundings of the Dutch people, depicting “the Sunday of life which equalizes everything.” It was attuned to the present rather than the past.

This view became commonplace in nineteenth-century commentary. In one of the most influential texts, French artist and critic Eugène Fromentin claimed that an essentially Dutch art emerged from a radical break with the recent past. He wrote that seventeenth-century painters found themselves “on the horns of a strange dilemma,” for the cleansing of the churches had left them with banned and broken artworks and traditions. In response, Fromentin famously asserted that the Dutch turned to the world around them and “began to paint a portrait of the new situation.” Church art and history paintings ceased to dominate artistic production, which was radically redefined by the efflorescence of realistic scenes of everyday life. Eschewing religious, historical, and mythological subject matter, Dutch realism redirected its gaze to aspects of the country itself: the faces of its citizens; its ever-changing skies and seas; the land with its inhabitants; all the minutiae of domestic life; urban scenes of city streets and canals, public gathering places, and prominent buildings. In contrast to religious and history painting, this realism was a nonnarrative art that drew inspiration from the visible world rather than from texts. Iconoclasm’s wake forced artists to grapple with the changed status of their work.

In turn, the new art of the everyday generated new kinds of responses from beholders, who had to come to terms with the absence of explanatory texts. Sir Joshua Reynolds, on a journey through Flanders and Holland in 1781, prefaces his description of the Dutch art collections with the bald assertion that “history has never flourished in this country.” He concludes that the merit of the Dutch pictures “often consists in the truth of representation alone. . . . It is to the eye only that the works of this school are addressed.” Modern criticism has often followed the provocative lead of observers such as Fromentin and Reynolds. Dutch art, as Svetlana Alpers has argued, is an art of describing: “The fact that Dutch art was so often independent of the texts that were the basis of history paintings made them also independent of commentary . . . you cannot tell the story of a Dutch painting, you can only look at it.”

Fromentin’s countryman, the socialist art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger, coined an apt slogan to capture this new visibility of the present: “À société nouvelle, art nouveau” (A new art for a new society). In this light, Dutch art appears revolutionary, even avant-garde. As Simon Schama claimed in The Embarrassment of Riches, the seventeenth-century Dutch worked out a new kind of cultural identity by differentiating “between a new ‘us’ and an old ‘them.’” They were acutely aware of “fresh historical experience” in “the springtime of their nationality.” Dutch realism accordingly has been characterized as a radical art, born together with the nation itself. It was forged in the moment that Van Delen represents (fig. 4), from the hammer blows of the iconoclasts.

A curious corollary to this pervasive myth of origins is, however, the claim that Dutch realism was indifferent, even evasive, with regard to Dutch history. The struggle and suffering of the immediate past—reformation, revolt, and iconoclasm—do not reverberate through these joyous depictions of the everyday: “Do the people remember it? Where do you find living echoes of these extraordinary emotions?” asks Fromentin. According to this view, the anxious troubles and turbulences of history are eluded in the surprising calm of the imagery. In effect, paintings repress the pain of the past beneath their smooth surfaces.

In these terms, the realism of church painters such as De Lorme appears as simply a portrait of the new historical situation in which the Dutch Republic found itself, one in which history and narrative seem to have been banished from the arena of representation. Indeed, in his pioneering analysis of architectural paintings, Hans Jantzen adopted Fromentin’s insights and characterized the seventeenth-century Dutch works as “church portraits,” a label that recurs in the literature on this subgenre. And there followed numerous lyrical prose descriptions of the quiescence that imbues such portraits. Swillens’s 1961 catalog essay for an exhibition of Pieter Saenredam’s works provides an example: “He observed the lofty church, surrounded by high bright walls broken by narrow windows, which transmitted a mild and diffused light embracing the entire space. He created a richness of nuances, never shrill nor gloomy, always soft and transparent, soothing and subdued. . . . There is nothing at all liable to break the stillness, nothing that would suggest movement, everything tending rather toward introspection and contemplation.” In an essay in the same catalog, the art historian I. Q. van Regteren Altena cannot resist situating Saenredam’s churches in Hegel’s Sunday of life: “The whole of the seventeenth century reminds us of one long Sunday, during which the Dutch gradually awoke after the evil dream . . . of which the shaken minds of the older generation had but slowly recovered. It resembled a day of rest when people . . . had leisure to explore with new eyes, and to find inexhaustible joy in studying every aspect of God’s creation, and work done by the hand of man as well.” Awaking from nightmares of the past, Saenredam’s generation of artists was free, these descriptions suggest, to explore the world around them. Their forebears had suffered through revolutionary times, but the reward was peace, and a peaceful form of art resulted. According to this Hegelian formulation, Dutch art serves as a means of forgetting the past. Having thrown off repressive ecclesiastical and aristocratic patronage, it can now explore a new situation with new eyes. It does not look back.

Recent scholarship has begun to revisit the familiar characterization of realism as a placid art of the everyday that eschews the upheavals and drama of history, religion, and politics. This book, and the church interior paintings at the heart of it, press for further reconsideration of the received account. After all, there is a peculiar paradox at work in the meticulous visual portrayal of a new situation in which works of art are destroyed and replaced with visual displays of the Word (fig. 3). As the following chapters will explore, the idiosyncrasies of this genre—its particular modes of interrogating the complexities of reformed spaces and specific ways of soliciting the engagement of potentially diverse viewers—prompt us to see realism’s committed engagement to Dutch politics and history, and also to art’s own history. These representations of emptied churches are not as barren as they first appear; indeed, as the literature suggests, they tell us much about how the Dutch reinvented themselves in the realm of painting. However, the process of making a new art for a new society cannot be characterized solely in terms of repudiation of the past. As we have already begun to see, paintings of the emptied churches induce a tension between profound historical losses and the new situation. The particular aesthetic qualities of these works indicate how alienation and liberation together were part of this multivalent process of creating a new “us” in contrast to an old “them.”

In fact, Van Regteren Altena’s own insights about Saenredam already begin to work against his description of the paintings in terms of “a day of rest” during which people could recover from the past by finding pleasure in the visual delights of the present. Interrogating their aesthetics of emptiness, he describes how these paintings actually record and preserve Gothic interiors in close detail, including the often fragmentary material remains of Roman Catholicism. Saenredam, he concludes, was an archaeologist. Far from eradicating the material past in favor of the here and now, iconoclasm seemingly generates an opposing impulse: the archaeological preservation of this material. The selective realism of these forward- and backward-looking paintings conveys the palimpsestic qualities of bare walls and of history itself. For the discordant past of the churches was only partially effaced and overwritten with the texts of the new religion. In the following chapters, we shall see that in spite of the destruction wrought by the iconoclasts, these interiors were never completely stripped: things like wall and ceiling paintings, stained-glass windows, organ cases, and grave markers all survived as visual reminders of past functions. Moreover, as the studies of C. A. van Swigchem and Mia Mochizuki have shown us, the Calvinist churches were never actually empty. After iconoclasm, the Calvinists filled the churches with new forms of visual culture. The text boards, church furnishings, and funeral hatchments visible in De Lorme’s paintings are typical of this kind of decorative program, suggesting how the new material culture of Calvinism coexisted with vestiges of Catholicism. In the following chapters, I analyze a number of church interior paintings that highlight conspicuous material evidence of the contesting histories visible within these centuries-old interiors. As Van Regteren Altena suggested, to paint these churches was akin to archaeology, allowing for stratigraphic examination of a multilayered site.

By preserving the remains of the past, such paintings open up an active and ongoing relationship with history. In point of fact, it was the historical significance of these buildings that first engaged Saenredam, a pioneer of this distinctive subgenre. He began depicting the church interior as part of a larger historical project, making commissioned drawings for engraved illustrations of a civic history of Haarlem. Civic histories proliferated in the seventeenth century in tandem with architectural paintings of public buildings, markets, city squares, street views, and cityscapes. Church interior painting is part of this broader postrevolt interest in urban changes and urban achievements, and participates in the desire to create new pictorial and textual histories for the independent Dutch cities. At the same time, as repositories of historical memory, paintings of the Gothic churches are closely connected to the numerous landscape and cityscape paintings that focus on the ruins of damaged or partially destroyed medieval castles, abbeys, cloisters, and churches. Picturing traces of a damaged past, such imagery allowed viewers to see how the new republic was built out of the ruins of Roman Catholic feudalism.

In short, in spite—and because—of their ostensible vacancy, the Gothic Calvinist churches were intriguingly hybrid public spaces: ruins of a sort, they simultaneously remained key civic buildings, intricately tied to contemporary religious and political power. Consequently, to paint these gigantic halls meant also to work against iconoclasm’s always incomplete imposition of forgetfulness, calling to mind how such apparently calm spaces were created out of an aggression against their own histories. For all their plainness, such interiors, as Kundera points out, register the passage of history. However strangely, their white walls give visual access to the violent founding events of the Dutch Republic. In turn, by representing visibly altered interiors, realist paintings of the Calvinist churches do not only depict the here and now, but simultaneously recall a long and painful historical process of alteration. In meticulously reproducing the contradictory archaeological layers of these walls, they reveal how new power structures contained within themselves remnants of their own incompatible pasts. As this book will argue, such paintings remember a material past that was, in all senses of the word, reformed rather than eradicated.

The complex challenge posed by these palimpsest-like works is underscored by the range of investments of their viewers, which suggests that responses to them cannot simply be reduced to an affirmation of the Grand March of History, nor to backward-looking regret for a Dutch past in ruins. Patronage patterns point instead to a much wider variety of potential reactions. The important archival research of John Michael Montias indicates that paintings of churches were relatively expensive works that were collected mostly by wealthy, influential citizens, many of them Calvinist. The members of this socially prominent group can be seen as the victors in recent struggles: they would have had some investment in the Grand March, and may have invested accordingly in impressive paintings that documented the Calvinist appropriation of these important buildings. Yet the work of Gary Schwartz and Marten Jan Bok shows that the Dutch Republic’s Roman Catholics also commissioned and collected church interior paintings. As we shall see, the Catholic community maintained a profound attachment to the churches that they had lost but hoped to regain. In such cases, the archaeological layers explored by painters like Saenredam must have appealed to those who identified closely with former histories and meanings.

But even this not unexpected religious divide does not adequately explain the sheer diversity of interest in church interior paintings, which extended well beyond Dutch Calvinists and Roman Catholics. Members of Amsterdam’s wealthy, art-collecting Sephardic Jewish community saw how this style of painting could be adapted to their interests. The church interior painter Emanuel de Witte made at least three paintings of the interior of the lavish new synagogue, and the evidence indicates that these were owned by Jewish collectors. Others, like the Catholic foreigner Monconys, seemed to value interior views of the churches chiefly for their aesthetic qualities. His comments about De Lorme’s paintings convey appreciation for the skill of their making. Indeed, Dutch church interior paintings were esteemed throughout Europe for their aesthetic qualities, appearing in a number of prestigious international collections.

As I argue in this book, seventeenth-century depictions of church interiors were hybrid both in their visual content as well as in their appeal to a diverse range of art buyers. They were bought by wealthy citizens interested in the redefinition of civic identity. They engaged the differing historical interests, political positions, and religious beliefs of both Calvinists and Catholics. They are listed in the inventories of Jews, Lutherans, and Mennonites. Nor were these artworks limited to local concerns. The fact that Monconys wanted to buy a painting of the interior of Rotterdam’s main church demonstrates the broader allure of local imagery, which crossed national and religious boundaries. This breadth of appeal was due in no small measure to the subtle and skillful manner in which paintings like these investigated the new conditions of possibility for the visual arts after iconoclasm. Their formal qualities and subject matter together probe the complex interweaving of artistic innovation with damaged traditions—certainly a matter of fascination for anyone concerned with art and its troubled history.

Realism’s Religion? Calvinism and Dutch Art

The fact that these church paintings were not simply Protestant pictures for Protestant buyers presses us to reconsider of some of the connections that have been made between realism and Calvinism. Clearly, Hegel’s assertions that the Reformation was completely accepted in Holland and the communal values of Protestant republican autonomy were expressed in works of art that were “concretely pious in mundane affairs” are no longer credible. The Calvinist Church did emerge from the revolt as the politically sanctioned public church and accordingly took a stance against the previous religious and political regime. The actual number of professing Calvinists was never large, however, and Roman Catholics remained a significant group. Within the densely populated trading cities especially, Dutch people of various faiths cohabitated closely with a global array of immigrants. As one observer described the republic’s unusual diversity, “It is well known . . . that in addition to the Reformed, there are Roman Catholics, Lutherans, Brownists, Independents, Arminians, Anabaptists, Socinians, Arians, Enthusiasts, Quakers, Borelists, Muscovites, Libertines, and many more . . . I am not even speaking of the Jews, Turks, and Persians.” From this we can conclude that Calvinism was a dominant religious view, but never the homogenizing mentality that Hegel described.

This book accordingly rethinks the complicated question of Calvinism’s influence on the arts. The writings of Johan Huizinga eloquently elucidate the problematic: “We must now return to a problem we have left unsolved, namely the extent to which Calvinism stimulated the development of Dutch culture. Was it no more than the leaven in the lump of religious life? Or was it rather the driving force behind the intellectual and social improvement of this young nation; did it help to crystallise Dutch thought, to fertilize Dutch art?” Huizinga concludes, “Those who try to answer these questions will quickly find that they are working with imponderables.” Imponderability has proven to be a stimulus, and two predominant and opposing strands of scholarship have emerged from an engagement with these issues. One approach argues that Dutch painting developed independently of religion in a sphere that evaded its controls, whereas the other maintains that this art has a strong religious and moral foundation based in Calvinism. There is much at stake here, for the difficulty of reconciling Dutch visual culture with its religious context actually structures many art-historical studies of the period. The main methodological approaches to Dutch art—formalism, iconography, and contextual studies in particular—were in part devised as means to grapple with this very problem. Incompatible solutions have resulted. How can we resolve the claims that art and faith inhabited separate spheres, that some artists and patrons were motivated by private beliefs, and that religious meanings were embedded in the iconography of Dutch art, for instance? This impasse is symptomatic of larger methodological battles that have enlivened the study of Dutch art and impacted the discipline of art history more broadly. It is worth reviewing the historiography of the vexed art-and-religion question, therefore, for it has framed the ways we interpret and understand post-Reformation art.

Max Weber’s succinct summation of the separate-spheres argument provides a useful starting point: “The fact that in Holland a great, often earthily realistic art could develop only goes to show the limitations of authoritarian controls over morals in these areas. Once the brief dominance of the Calvinist theocracy had given way . . . and the strong ascetic appeal of Calvinism had waned, the influence of the court and the regents and of the pleasure-seeking newly rich petite bourgeoisie proved too strong.” In this passage, Weber attributes the flourishing of down-to-earth Dutch realism to the failure of churchmen to impose their distinctive brand of asceticism. Surprisingly, someone as attentive to Calvinism’s pervasive and oft-unintended influences as Weber assumes that the Calvinist Church played a predominantly negative role in cultural production, an argument that is reiterated frequently. According to this view, Calvinist image interdictions successfully targeted perceived abuses of visual and material culture in the religious realm, but had negligible impact on the widespread production and consumption of art.

Such a conclusion derives from Hegel’s influential assertion that the connection between art and religion was broken in the post-Reformation period. Hegel saw in Dutch art evidence of a larger historical pattern of change: a waning of religious subject matter in favor of images of the everyday world. Art does not merely turn to the imitation of the visible world in this phase, however. Instead, emphasis shifts to the unique capabilities of artists to invent autonomous artistic forms: “what is most important here is the individual recreation of the external world. . . . Consequently the interest in the objects delineated tends to revert to the fact that it is the unique powers of the artist himself which are thus consciously displayed.” In this way, the everyday content of Dutch realism serves as pretext for the creative abilities of artists in the free exercise of formal innovation.

This compelling strand of Hegel’s argument runs through the literature on church interior paintings, where substantial scholarly work has been guided by questions concerning the development of form and style. Primary source evidence certainly supports the claim that the appeal of these paintings derived from their formal innovations. In seventeenth-century inventories, for instance, church interiors were most often classified as “perspectives,” doubtless because their skillful rendering of large, empty architectural spaces foregrounds mastery of the intricacies of linear perspective. In spite of widely divergent religious affiliations, art collectors obviously did share an appreciation of the purely aesthetic qualities of these well-crafted works. As we noted, the art collector Monconys saw more value in De Lorme’s artistic abilities than in the uninteresting subject matter he painted. While the empty church itself offered nothing considerable, a painting of it was worth purchasing. The prototype may not enchant, but the image does. With the repression of religious subject matter, the valuation of painting itself changed. As Fromentin concluded, “The works have a value that things [in them] do not seem to possess.” In this way, the works themselves demand formal analysis: a painting of a whitewashed wall cannot help but call attention to the application of paint on a flat surface.

Formalism thus remains an important methodology, albeit one that has been challenged and rethought. Breaking with the formalist approach of many of his contemporaries, Erwin Panofsky shifted the emphasis from autonomous form to the investigation of culturally embedded content that only looks mundane on the surface. The Reformation, he argues, “affected iconographical subject matter rather than expressive form.” In this view, the everyday motifs of genre imagery convey disguised moral messages, so that seemingly secular images are imbued with a religious sensibility. Intriguingly, this line of argument can also be linked with Hegel, who vacillated about the connection between religion and Dutch art. Alain Besançon highlights a significant tension: “As Hegel observes, almost with regret, [Dutch painting] was not devoid of a certain spirituality.” While Hegel forcefully argued that the bond between art and religion was severed in the post-Reformation phase, he concurrently conceded that Dutch painting had a religious foundation and was concretely pious in mundane affairs. Iconography has been the dominant method for discerning this underlying piety in realism’s prosaic subject matter.

In part, the success of this methodology for the study of Dutch art can be attributed to how well it meshes with seventeenth-century Calvinist convictions that every human activity should be directed to the service of God and that all things are permeated with religious significance. It therefore follows that art making itself could be understood as an activity directed to the service of God, making artists’ biographies key to intended meanings. Connected to this is the idea that the beholders of paintings also were steeped in religious doctrine, which allowed them to apprehend and decode the hidden moral symbolism of images in ways no longer habitual to us. By shifting the focus from form to content, iconography offers an important corrective to the separate-spheres approach. For although the modern division of religious and secular spheres may have been nascent in the seventeenth century, it certainly was not fully established. Hegel’s vacillation implies as much. Methodological approaches based on the anachronistic division of religious faith from secular culture thus risk functioning, in Charles Taylor’s terms, as “subtraction stories,” accounts of modernity as a process that sloughs off earlier impediments, such as religious frameworks of understanding, in the progress to an exclusively secular humanist society.

Iconography works against this impulse, reminding us that seventeenth-century people did not look at paintings with modern eyes. In spite of these strengths, critiques of iconography’s limitations are well rehearsed. I would emphasize that this approach often conveys the determinist notion that Dutch art relays essentially Calvinist messages, or a generalized religious and moral mentality, hence foreclosing questions of how these paintings circulated within and beyond a complex plural society shaped by diverse religious beliefs and cross-cultural connections. Indeed, this method often founders when confronted with the multiple possible interpretations generated when realism’s ambiguous motifs are teased out using enigmatic emblem literature.

The limitations of iconography have fostered other contextual approaches, most notably Alpers’s innovative The Art of Describing. Alpers concisely summarizes the difficulties of interpreting the content of Dutch art in relation to its religious context: “Neither the confessional change, nor the confessional differences that existed between people in Holland in the seventeenth century seem to help us much in understanding the nature of the art. To the argument that secular subject matter and moral emblematic meanings speak to Calvinist influence, one must counter that the very centrality of and trust to images seems to go against the most basic Calvinist tenet—trust in the Word.” In this passage, Alpers’s influential critique of the iconographic method is framed in terms of the difficulty of resolving the question of Calvinist distrust of the visual image. Ironically, a study that proposes a new theoretical and methodological model based on closer attention to “the place, role and presence of images in the broader culture” concludes that religious context cannot help us to understand the nature of Dutch art. Alpers accordingly (and productively) shifted the main framework of understanding to an exploration of the relations between Dutch pictures and seventeenth-century experimental science and technology.

Art-historical scholarship has recently returned to the troublesome question of religion, offering productive ways to move beyond the scholarly impasse I have sketched out. The significant work of Hans Belting, Joseph Koerner, and Victor Stoichită in particular explores the wide-ranging impact of Reformation debates about the uses and perceived abuses of visual imagery, which sharpened the definition of what constituted a work of art and challenged conventional understandings of the roles of artists, patrons, and viewers in the early modern period. In this view, plural and contesting faith practices were a vital part of cultural life. Not isolated and contained in a separate private sphere, religious beliefs were central to public life, a predominant means of structuring knowledge and visual experience. In response to Huizinga’s key questions about the cultural influence of Calvinism, I would therefore contend that it was religious diversity, rather than solely Calvinism, that helped to fertilize Dutch art. Artistic traditions did change significantly after iconoclasm, and this book argues that the new visual forms that emerged in the religiously plural post-Reformation period reveal much about the contentious debates that shaped them.

In this regard, Alpers’s central claim—that visual culture was vital to the life of Dutch society and visual experience a predominant mode of self-consciousness—gives us a constructive means of rethinking the art and religion conundrum. The claim is indebted to Hegel, who argues that art should not just provide accurate depictions of the world as seen, nor should it be reduced to a medium for individual self-expression. Acting as a mediator between the subject and the world, art, like religion and philosophy, is a mode of thought, a vehicle for human self-awareness. Indeed, when we approach paintings of the interiors of Calvinist churches in Stoichită’s terms, as self-aware images, we see how such imagery reflexively interrogates its own place, role, and presence in the broader context. De Lorme’s works (figs. 1 and 3) are evocative of how this genre situates itself at the interface of the politically contentious histories of art and religion. This body of imagery documents, emerges from, influences, and questions the changing status and functions of visual imagery and visual experience in the wake of iconoclasm and political revolt. The two chapters that comprise part 1 of this book, “Painting the Church,” foreground this set of issues. They examine some of the metapictorial strategies of two complex pictures by Pieter Saenredam and Emanuel de Witte, apprehending them as material forms of thinking about the shifting history and transformed conditions of the image after iconoclasm. In response to Alpers’s summation that “neither the confessional change, nor the confessional differences that existed between people in Holland in the seventeenth century seem to help us much in understanding the nature of the art,” I would counter that it is actually the nature of the art itself that tells us much about how religious change and confessional diversity were managed.

This book accordingly focuses on paintings that are reflexive about their own position in the aftermath of iconoclasm. Not intended as a comprehensive survey of the range and development of Calvinist church interior paintings, it is organized thematically rather than chronologically while taking into account how the genre changes over the course of the seventeenth century, responding to diverse needs at various times and in different cities. Chapter 1, “Time-Stained Walls,” examines Saenredam’s Interior of the Buurkerk at Utrecht. I argue that Saenredam was a painter of surfaces and that the idiosyncratic formal qualities of his work insistently draw attention to the changed status of the reformed Gothic church—and to the changed status of painting itself—as material-worldly things that no longer served as conduits to a transcendent beyond or as repositories for established doctrines. This chapter analyzes the painting’s enigmatic pictorial motifs: graffiti drawing, a painted Ten Commandments board, and turbaned Islamic staffage figures who look around the church. Moving away from iconographic moral meanings, I explore how these interconnected motifs interrogate the distinctive visual culture of Calvinism. By limiting his artistic field to the time-worn surfaces of the whitewashed wall, Saenredam calls up the long history of the church, while concurrently highlighting the new modes of viewing, picture making, and visual experience that the emptied churches provoked. In this way, I argue that the Interior of the Buurkerk provides ways for its viewers to critically engage with the complex question of Calvinism’s impact on visual art and material culture.

Saenredam often is heralded as a pioneer of the new Dutch realism, which raises questions about how the truth claims of realism rub up against Calvinist distrust of the image. This issue comes to the fore in Chapter 2, “The Forbidden Image,” which takes up a remarkable picture by Emanuel de Witte. In his strikingly realistic painting of the Old Church of Amsterdam, De Witte has inserted an emphatically anachronistic element: the Vera Icon, a powerful religious image once central to this space and its cult. By incorporating this forbidden relic of a conquered past, the painting is able to picture the historical past together with the spatial and pictorial transformations brought about by the ban on sacred imagery. Moreover, in its startling juxtaposition of actual and imagined elements, De Witte’s realism throws into question its own mimetic accuracy. Indeed, as we shall see throughout the book, church interior painters often employed a range of formal devices such as painted picture curtains and trompe l’oeil frames, which self-reflexively draw attention to skillfully wrought, captivatingly deceptive surfaces. Distrust about the truth of the image is thus wittily expressed through the medium of painting itself. Such paintings do not ask viewers simply to believe in the image or to be tricked by its mimesis. Instead they challenge beholders to interrogate realism itself as a form of visual knowledge. This productively challenges the notion that Dutch realism merely aims to duplicate the visible world. Instead, I argue that De Witte’s painting self-consciously calls attention to the gap between the visual image and its prototype. This opens a space for new critical possibilities in which the wit of the artist and the aesthetics of the work together solicit the painting’s beholders to do the creative interpretative work of generating meanings. Artistic meanings are no longer authorized by a religious cult here, but are produced in the exchange with a viewer who completes the work. By highlighting the dramatic change in status and authority of the icon, De Witte’s painting, I conclude, draws attention to its own powers and thus crafts a new public role for art.

The two chapters comprising part 2 of the book, “The Transformation of Public Space,” consider visual representations of the reformed Gothic church interior in connection to significant changes in public life. Chapter 3 analyzes paintings that foreground the many internal contradictions of these churches. These representations remind viewers that the desacralization of religious space was an incomplete process of compromise, and that the new public church was never fully reformed into an essentially Calvinist space. Clandestine Roman Catholic practices persisted in spite of Calvinist efforts to redefine these ancient buildings. Moreover, because the churches were owned by the cities, they provided space for a range of civic and social functions that could conflict with Calvinist claims on the buildings. The fact that many church interior paintings highlight nonreligious aspects and uses is suggestive of the disparate interests of the varied group who collected these works. This chapter also examines sermon paintings, which draw attention to contradictions within the Calvinist worship service itself, where professing Calvinists were joined by quite a broad spectrum of the population. In conclusion, I argue that these paintings indicate how the many inconsistencies of the multifaceted church interior allowed for the accommodation of diversity, albeit in tension with church doctrines. The Calvinist Church thus emerged as a new type of public religious space that was surprisingly open and plural.

Chapter 4, “Monumental Space,” focuses on the political functions of the Calvinist church interior. It takes up an important and much-painted political monument in Delft’s Nieuwe Kerk: the sepulcher of the first stadtholder, William of Orange, military leader of the Dutch Revolt. Analysis of this monument and the many representations of it reveals how the fraught ideal of a body politic functioned in the Protestant republic. The chapter first assesses the contradictory status of the monument, whose monarchical visual idiom and location in the church choir excited much comment. I then turn to a series of formally innovative church interior paintings of the tomb, which emerged at the onset of the First Stadtholderless Period in 1651. Here I argue that the reinvention of the monument in paint during this time of political crisis is interconnected with a significant transformation of the public sphere. Resisting the assumption that art was complicit with the powers and institutions of religion and politics, my analysis centers on the critical possibilities offered by paintings that present oblique glimpses of the stadtholder’s monument at the time of the stadtholderate’s demise. These paintings, I argue, represent a new approach to politics. Instead of imposing authorized messages, they were designed to be sold on an open art market, where they had to provoke the interests of a wide range of beholders who held divergent views about the republic’s complex political and religious traditions. Indeed, the very open-endedness of these paintings highlights the fact that their public functions were dramatically different from commissioned religious and political works of art—like the altarpiece and the monument of Orange that replaced it—which had dominated artistic production in the past.

This conclusion has significant implications for reconsidering the functions of realist paintings in general and paintings of the contentious Calvinist churches specifically. One of the key characteristics of nonnarrative descriptive art is its strange capacity to generate multiple, even contradictory, interpretive possibilities and seemingly incompatible meanings. I contend that the inconsistencies produced by the iconographic method do not have to be reconciled when the process of interpretation itself is considered in terms of the circulation of these paintings in their specific context. While some paintings were designed with the interests of particular patrons in mind, the majority were sold on the open market, where they had to appeal to the disparate concerns of anonymous buyers. In this context, the attraction of these works derives from their well-crafted ambiguity. The paintings seldom impose one definitive meaning; instead they pose questions and solicit their beholders to tease out various possible answers in processes of creative interpretation. This does not foreclose the possibility that devout Calvinists saw moral messages in specific iconographic motifs. Probably they did. But another viewer might tease out radically different or even opposing meanings from the same motif. Thus, I argue that the distinctive qualities of Dutch realism—its formal pleasures and enigmatic subject matter—were designed to address and attract a very wide variety of art buyers within a context of unusual religious and cultural diversity.

These idiosyncratic artistic forms did not just generate multiple meanings; the very process of interpretation had the potential to create new kinds of social formations and understandings of public life. As we have already noted, older social traditions structured by church and monarchy altered dramatically after the Reformation and the Dutch Revolt. Religious and cultural historians have recently characterized the new kind of public life that emerged in terms of discussiecultuur. A vibrant culture of discussion was engendered by the widespread circulation of various media to a broad spectrum of the population. This dissemination allowed people with differing opinions and beliefs to debate matters that were of common concern to them. Discussion accordingly was a prevalent means for people to manage the many tensions of diversity. In the process, the actions and opinions of private people began to play a larger role in the structuring of society itself. This prompts an important rethinking of the connections between specific cultural forms and their broader context, productively moving us beyond older frameworks of understanding in which the general mentality or Geist of a collectivity is expressed in its culture. In a culture of discussion, people are not bound together by pre-established identities based on religious or political beliefs, or by innate national characteristics. Rather, it is shared access to a range of cultural forms that draws people together, not in unity but to argue, understand, and possibly reassess their manifold differences.

The circulation of enigmatic paintings in the context of discussion culture did not necessarily resolve religious and political differences; rather, it opened them to debate. Memories of the violence done to a shared past and to traditional public life flared up repeatedly, especially in times of crisis. The chapters in part 3 of the book, “The Work of Mourning,” take up images that picture the aftermath of iconoclasm in terms of death, loss, and remains. Chapter 5, “Unresolved Histories,” emphasizes the investments of different historical communities in the republic’s churches by examining depictions of the dramatic events that accompanied the restoration of Utrecht’s cathedral to Roman Catholicism after the French invasion of 1672. In the reactions to this unanticipated reversal, it becomes painfully evident that the incompatible histories of the Dutch churches had never been reconciled. Indeed, unresolved histories were acted out in a series of traditional ritual practices such as religious and political processions, and in iconoclastic attacks on the church, first by Catholics and later by Calvinists. I interpret these actions as evidence of the extreme difficulty of coming to terms with religious and political losses of the past. In addition to works by church interior painters, the chapter analyzes the many printed images that represented events in and around the cathedral. At this time of crisis, the medium of print was mobilized to circulate information about the French occupation throughout the republic, satirically probing at its ramifications and thus exposing those involved to the judgments of discussiecultuur.

The sixth and concluding chapter, “Death and Dutch Art,” considers paintings that focus on the church as burial place. Through creative engagement with death and its remains, this imagery explores multiple ways that the churches materialized losses in the political, religious, aesthetic, and personal domains. By orienting themselves in relation to death, which lies beyond the purview of representation, these paintings foreground their own worldliness. Worldly art is locked in a battle with mortality: it strives to make the fleeting endure, even as it acknowledges its own earthly transience and vulnerability in the wake of iconoclasm. By turning to the material world of everyday life, realism thus self-consciously struggles with its own limitations and ambiguities. It is in this very loss of certainty that the paintings locate their unique potential, not only to provoke critique of the world they depict, but also to create a new world in the realm of painting. Paintings of tombs and grave markers thus point to the future as much as they signal the past, for they are attentive to their own potential to bring something new to the context they interrogate.

I have entitled this book The Wake of Iconoclasm for two reasons. Paintings of Calvinist churches develop in the aftermath of iconoclasm. They picture its aftereffects, the disturbances caused by a powerful movement that swept through the churches. A wake is also a time of remembrance, and this imagery is attuned to the losses associated with iconoclasm. To contemplate carefully the bare walls of an emptied church was a means of remembering an attack on the spiritual and political beliefs of one’s ancestors and the assault on their most sacred forms of material culture. This imagery bears witness to these broken traditions, actively working through and out of them. By remaining open to an unfinished past, these paintings allow the creative work of mourning to occur. This encompasses more than backward-looking nostalgia or utopian longing to restore a lost past. Following from the insights of Paul Ricoeur, I understand mourning as a way of making sense of the past in the present and for the future: it can do the work of “correcting, criticizing, even refuting the memory of a determined community.”

The churches were complicated communal spaces; as new ideals of community were forged in the seventeenth century, paintings of these public sites reveal the impossibility of whitewashing away the past, no matter how incompatible. The paintings expose what whitewash attempts to conceal: that the Dutch were very much alive to the irreconcilable shared past of their own diverse community. In what follows, we shall see how these ostensibly still and peaceful paintings touch on matters of deep dissent, opening them up for deliberation and debate by refusing to be silent about artistic, religious, and political histories that remained in many ways unresolved.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.