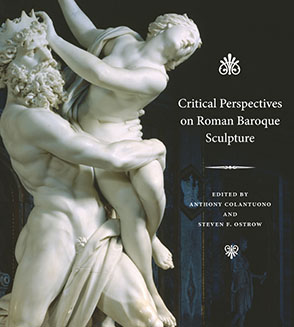

Critical Perspectives on Roman Baroque Sculpture

Edited by Anthony Colantuono and Steven F. Ostrow

Critical Perspectives on Roman Baroque Sculpture

Edited by Anthony Colantuono and Steven F. Ostrow

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association

“The reader is sure to be disappointed that there is not another volume on hand to continue the story through the eighteenth century. Of course, the challenge of this sequel would be to find a similar group of authors who could approach their topics with the highest imagination and argue their points as persuasively—and there would also need to be editors like Colantuono and Ostrow, ones intent on uncovering the nitty-gritty of the era’s sculptural practice.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Aside from the editors, the contributors are Michael Cole, Julia K. Dabbs, Maarten Delbeke, Damian Dombrowski, Maria Cristina Fortunati, Estelle Lingo, Peter M. Lukehart, Aline Magnien, and Christina Strunck.

“The reader is sure to be disappointed that there is not another volume on hand to continue the story through the eighteenth century. Of course, the challenge of this sequel would be to find a similar group of authors who could approach their topics with the highest imagination and argue their points as persuasively—and there would also need to be editors like Colantuono and Ostrow, ones intent on uncovering the nitty-gritty of the era’s sculptural practice.”

“This collection by Anthony Colantuono and Steven Ostrow is the most important contribution to general sculpture studies of the period since Jennifer Montagu’s Roman Baroque Sculpture, to which it is the ideal complement. And, frankly, I can think of no higher praise for a book with such breadth of scope, clarity, and substance. The introduction is a ‘must-read’ for all students of the topic. In all, this is an impressive contribution to our literature.”

“This important collection of essays challenges, corrects, and changes common views on seventeenth-century sculptural practice and theory in Rome. It debunks academic fairy tales such as Mochi's enervated late style or Bernini's disinterest in relief sculpture. Through a multitude of methodological approaches, this volume elucidates the central role of early modern Roman sculpture for European visual culture and thought at large—and it will have repercussions far beyond its own focus.”

“This book is certain to be an essential point of reference for any scholar broaching the subject of sculpture in early modern Rome. It is important for the diversity of its perspectives, the attention paid to particular works and genres, and the sophisticated analyses that breathe intellectual life back into the cold stone, all of which are prefaced by a much needed and comprehensive review of the historiography of the field.”

Anthony Colantuono is Professor of Art History at the University of Maryland.

Steven F. Ostrow is Professor and Chair of Art History at the University of Minnesota.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Steven F. Ostrow and Anthony Colantuono

1 The “Accademia dei Scultori” in Late Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Rome

Peter M. Lukehart

2 Francesco Mochi: Stone and Scale

Michael Cole

3 Impossible Apostles: Francesco Mochi’s Saint Peter and Saint Paul for S. Paolo fuori le mura

Estelle Lingo

4 The Poetry of Atomism: Duquesnoy, Poussin, and the Song of Silenus

Anthony Colantuono

5 Orfeo Boselli’s Osservationi della scoltura antica: A Seventeenth-Century Treatise on Sculpture, Its Purpose, and Its Descent into Obscurity

Maria Cristina Fortunati

6 The Sculptural Altarpiece and Its Vicissitudes in the Roman Church Interior: Renaissance Through Baroque

Damian Dombrowski

7 “For we are made a spectacle unto the world, and to angels, and to men”: Alessandro Algardi’s Beheading of Saint Paul and the Theatricality of Martyrdom

Maarten Delbeke

8 “Appearing to be what they are not”: Bernini’s Reliefs in Theory and Practice

Steven F. Ostrow

9 The Poisoned Present: A New Reading of Gianlorenzo Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina

Christina Strunck

10 “Humoring” the Antique: Michel Anguier and the Physiological Interpretation of Ancient Greek Sculpture

Julia K. Dabbs

11 On Causes and Effects: Imitating Nature in Seventeenth-Century Sculpture Between Rome and Paris

Aline Magnien

List of Contributors

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Rome as the Center of Early Modern Sculpture

Steven F. Ostrow and Anthony Colantuono

In his Vita di Gio. Lorenzo Bernino of 1682, Filippo Baldinucci tells us that when Paul V wanted to commission a sculpture to adorn the façade of his family chapel in S. Maria Maggiore, he obtained the services of Pietro Bernini, Gianlorenzo’s father. “Thus Pietro,” Baldinucci writes, “arrived in Rome [from Naples] with all his numerous family and established his residence. Here, in the world’s most celebrated capital, a larger arena opened for the exultant flights of Giovan Lorenzo’s genius. Only in that city could one admire the most celebrated works of ancient and modern painters and sculptors as well as the precious remains of ancient architecture which in spite of time, not an inconsiderable enemy, still stood miraculously in glorious ruin.” In the first decade of the seventeenth century, when Pietro Bernini and his family moved to Rome, the city was not just a “larger arena” than Naples but the most dynamic city in all of Europe for the study of ancient and modern art and, notably, for the production of sculpture as well. While Florence, Siena, Naples, Bologna, Milan, Venice, and other Italian centers could boast long and well-established sculptural traditions, only Rome could lay claim to millennia of sculptural practice and to being the birthplace of what would later be called “Baroque” art.

Many factors converged to establish Rome as the center of sculptural production and innovation in Italy and, for that matter, in Europe in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As the capital of the Roman Empire, it was, of course, the foremost repository for ancient sculpture, which could be seen and studied in the collections of Rome’s noble families, in the Vatican and Capitoline Palaces, and in situ—including the Dioscuri on the Quirinal Hill, the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius at the center of the Piazza del Campidoglio (since 1538), and the reliefs on the honorific columns, triumphal arches, and temples and other structures that filled the heart of the city. The passion for classical sculpture in Rome was without parallel, and, as Ludwig van Pastor noted, “in Rome, almost all private men of wealth possessed antiquities, and rooms, courtyards, and gardens were everywhere adorned with them.” Although Pius V (r. 1566–72) endeavored to rid Rome of its pagan statues and Sixtus V (r. 1585–90) attempted to transform pagan into Christian monuments, the cult of the antique not only survived but increased, and at the very beginning of the seventeenth century Clement VIII (r. 1592–1605) appointed his camerlengo, Pietro Aldobrandini, to issue an edict protecting the antiquities of the city.

The number of ancient sculptures in Rome increased dramatically over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with new works continually being unearthed. And alongside this increase in discoveries was an expansion in the trade of ancient statuary. Ciriaco Mattei (d. 1614), a member of one of Rome’s most prominent noble families and a renowned art collector, is exemplary in this regard. Between 1595 and 1599 he acquired a number of works for the garden of his Villa della Navicella: twelve ancient statues and “various kinds of animal heads” from the Savelli; ten ancient statues from the Santacroce; and another twenty antique sculptures from the Massimo. Many of Rome’s sculptors were themselves involved in the antiquities trade, and several provided Mattei with additional works. Over the last five years of the century he purchased, inter alia, an ancient satyr from Niccolò Pippi (d. ca. 1600); a statue (of uncertain subject) from Pierre de la Motte (documented in Rome 1568–1603); six ancient marble heads and a gladiator from Cristoforo Stati (1556–1619); and still more ancient statues from Flaminio Vacca (1538–1605). And throughout the seventeenth century other notable collectors, among them Scipione Borghese (Paul V’s cardinal nephew), Ludovico Ludovisi (Gregory V’s cardinal nephew), and the immensely wealthy banker, collector, and art theorist Vincenzo Giustiniani (1564–1637), were similarly engaged in the acquisition of ancient statues from other noble families and sculptors involved in the antiquities market.

Rome’s ancient sculptures, as Baldinucci’s passage suggests, were the foremost teachers of early modern sculptors. They were the standards against which all art was measured, and they provided the ideal to which all sculptors aspired. As Baldinucci also tells us, the young Bernini “spent three continuous years from dawn until the sounding of the Ave Maria in the rooms of the Vatican drawing the objects of greatest rarity,” a practice followed by most aspiring sculptors in the hope of being able to emulate the forms, expressions, and carving techniques of the ancient masters. But in addition to providing inspiration to sculptors—a “school for carving,” as Joachim von Sandrart called the Giustiniani collection of ancient sculpture—Rome’s antique statues and reliefs provided livelihoods for many sculptors, including some of the most famous of the period (including Bernini, Algardi, and Duquesnoy), who were involved in the restoration of ancient works, and many others were commissioned to make casts as well as full-sized and reduced copies of them. And while Giovanni Baglione, in his Le vite de pittori, scultori et architetti of 1642, wrote that “all men in this city [Rome] begin by restoring ancient objects,” many established sculptors who were well into their careers continued to execute restorations.

Thus, just as Rome’s vast corpus of ancient Greek and Roman statuary enabled the realization of the humanist vision of a mimetic dialogue with the art of the past, long before substantial remains of ancient painting had been recovered, it was precisely the often damaged, fragmentary condition of the ancient statues that not only helped build the highly demanding technical skills required of the restorer, but indeed also inspired all Renaissance and Baroque sculptors by setting the mind ablaze with wonder. If they were so beautiful in their damaged state, how much more exquisite must these ancient works have been in their pristine form? The antiquarian and artistic biographer Giovan Pietro Bellori, who would eventually hold the prestigious position of Commissario delle antichità in Rome (1670–94), tells the following story about his friend the painter Poussin:

One day when I happened to be with him [Nicolas Poussin] visiting certain ruins of Rome with a foreigner who was very keen to take some rare object back to his country, Nicolas said to him, “I would like to give you the most beautiful antiquity that you could desire,” and reaching down with his hand he picked up a bit of earth and some pebbles amid the grass, with specks of porphyry and marble reduced almost to dust, then he said, “Here you are, sir, take it to your museum and say: this is ancient Rome.”

The point of Bellori’s story is not merely to illustrate the sententious character of his friend’s ingenious wit, but to make a point about Poussin’s attitude towards antiquity—an attitude no doubt shared by the most astute visitors to the ancient city since the dawn of the Renaissance: while Rome’s ancient marvels may not survive perfectly intact, there is something even more precious, even more poignantly appealing, in their ruinous, fragmentary state, which permitted the early modern beholder (whether as artist, collector, or pilgrim) not merely to reconstruct archaeologically, but to invent, in the world of the imagination, an “antiquity” that perhaps never existed before. The broken fragments of classical sculpture offered many such opportunities, in which the Baroque sculptor’s work could seamlessly bond with antiquity through the act of restoration, or could revivify the art of sculpture itself with new works meant to rival those of the best ancient masters.

Although other Italian cities, such as Florence, Naples, and Ferrara, housed collections of ancient sculptures, and other centers, in Italy and beyond (such as Fontainebleau), had collections of copies of some of the most famous antique statues, Rome’s unparalleled trove of original ancient sculpture was a beacon calling artists from all over Europe who were eager to study the masterpieces of ancient art. But Rome’s attraction was not limited to its antiquities. By the last quarter of the sixteenth century and throughout the seventeenth century, the city offered more opportunities than any other for patronage. Once Rome had fully recovered from the calamitous sack of 1527 and began to be transformed—by the popes, members of the papal court, and the city’s wealthy noble families—into, in Baldinucci’s words, “the world’s most celebrated capital,” artists were in unprecedented demand to provide works of art for newly created and renovated chapels, churches, piazzas, palaces, and villas. Private (secular) patrons employed many sculptors who were called upon to produce portraits, small-scale sculptures in marble and bronze, fountains, and other works, as well as to restore ancient statues and to supplement their collections of antiquities with new works all’antica. But the greatest number of sculptural commissions came from the popes and other ecclesiastical patrons.

Following the Sack of Rome in 1527, the pontificate of Sixtus V (r. 1585–90) marked the reemergence of papal patronage on a truly grand scale—even greater than that of such builder-popes as Julius II (r. 1503–13), Leo X (r. 1513–21), and Paul III (r. 1534–49)—and during his pontificate the demand for sculptors rose meteorically. To cite just one example, for his burial chapel in S. Maria Maggiore—the Cappella Sistina—he employed more than twelve sculptors to produce the sculptural decorations, including Andrea Brasca (dates unknown), Prospero Bresciano (d. ca. 1593), Ludovico del Duca (d. after 1601), Egidio della Riviera (d. 1602), Francesco (Cecchino) da Pietrasanta (d. 1611), Pietro Paolo Olivieri (1551–1599), Giovanni Antonio Paracca il Vecchio (d. 1597, known as Valsoldo), Giovanni Battista della Porta (ca. 1542–1597), Niccolò Pippi, Leonardo Sormani (d. ca. 1590), Bastiano Torrigiani (d. 1596), and Flaminio Vacca. Hailing from Liguria, Lombardy, Tuscany, Sicily, Flanders, France, and Rome, they constituted an international team representing a wide range of sculptural styles. The same is true for Paul V’s chapel (the Cappella Paolina), also in S. Maria Maggiore, in which more than fourteen sculptors had a hand, among them Guillaume Berthelot (ca. 1580–1648) from Le Havre, the Florentine Pietro Bernini (1561–1629), the Milanese Ambrogio Bonvicino (1552–1622), Ippolito Buzio (or Buzzi, 1562–1634) from Viggiù, Nicolas Cordier (1565/67–1612) from Lorraine, the Tuscan Pompeo Ferrucci (1566–1637), Silla Longhi (1569–ca. 1622) from Viggiù, Stefano Maderno (1576–1636) from Palestrina, the Vicentine Camillo Mariani (ca. 1567–1611), Francesco Mochi (1580–1654) from Montevarchi, Cristoforo Stati from Bracciano, and Giovanni Antonio Paracca il Giovane (d. 1646) from Valsolda. Later in the century, Innocent X employed an even larger team of sculptors (no less than thirty-nine), working under Bernini’s direction, to carve the 56 medallions of popes, 192 cherubs, 104 doves, and other sculptural elements for the decoration of the pilasters in the nave and side aisles of Saint Peter’s. And, to cite one further example, for the decoration of the Ponte S. Angelo Clement IX (r. 1667–69) commissioned Bernini to make ten statues of angels carrying symbols of the Passion, which were carried out under Bernini’s direction by Antonio Raggi (1624–1686), Paolo Naldini (ca. 1615–1691), Cosimo Fancelli (ca. 1620–1688), Girolamo Lucenti (1627–1698), Giulio Cartari (active 1665–ca. 1691), Lazzaro Morelli (1608–1690), Ercole Ferrata (1610–1686), Domenico Guidi (1625–1701), and Antonio Giorgetti (d. 1670). Once again the sculptors involved in these two projects were from Italy’s many regions (Lombardy, Tuscany, Liguria, Sicily, and Emilia-Romagna) and beyond its borders.

Unlike other Italian cities, in which the guilds strictly regulated the practice of foreign artists, Rome welcomed them and allowed them to practice their profession freely. Peter Paul Rubens, Gerrit van Honthorst, Simon Vouet, Pieter van Laer, Nicolas Poussin, and Claude Lorrain are just a few of the many foreign painters who found success working in Rome, and, as noted above, numerous foreign sculptors also flocked to the papal capital. The majority of non-Italian sculptors came from Flanders and France. Among the Flemings were Gillis van den Vliete (known in Rome as Egidio della Riviera), Nicolas Mostaert (known as Niccolò Pippi), Jakob Cornelisz Cobaert (ca. 1530/35–1615, known as Cope Fiammingo), Pierre de la Motte (d. ca. 1603, known as Pietro della Motta), and the most famous and accomplished of them all, François Duquesnoy (1597–1643, known as Il Fiammingo). The French sculptors included Nicolas Cordier (known as Niccolò Cordieri or il Franciosino), Guillaume Berthelot (known as Guglielmo Bertolotti or Guglielmo Francese), Jacques Sarrazin (1592–1660), Michel Anguier (1612–1686), Alexandre Jacquet (1614–1686, known as Grenoble), Gervase Drouet (1609–1673), and Claude Poussin (d. 1661, known as Monsù Claudio). And following the founding of the French Academy in Rome in 1666, French sculptors came to the papal capital in increasing numbers, and many—among them Jean-Baptiste Théodon (1645–1713), Pierre Legros the Younger (1666–1719), and Pierre-Étienne Monnot (1657–1733)—received important commissions.

How many sculptors were there in Rome during the early modern period? The answer is uncertain, but clearly the painters outnumbered the sculptors. Among the slightly more than 200 artists discussed in Baglione’s Vite, which cover the period 1572 to 1642, 140 were painters and only 28 were sculptors (a ratio of 5:1). According to the census records from the time of Paul V’s papacy for the parish of S. Andrea delle Fratte, in which artists congregated, painters outnumbered sculptors 125 to 29 (a ca. 4:1 ratio), and for the parish of S. Lorenzo, in which artists also figured prominently, there were 231 painters and only 9 sculptors (a ratio of ca. 26:1). Of the approximately 400 French artists who were recorded in Rome between 1600 and 1700, 78 percent (or 312) were painters and 14 percent (56) sculptors, a ratio of ca. 6:1. If we discount the aberrational figures from S. Lorenzo and rely on Baglione’s numbers and the other data, we arrive at an average ratio of painters to sculptors of just under five to one. And based on the fact that there were about 200 painters in Rome in 1665, we can estimate that there were about 40 sculptors in the city—a number that accords with Jennifer Montagu’s statement, concerning the team assembled to decorate the pilasters in Saint Peter’s, that “just about every available sculptor was rounded up and set to work.”

Although many of the projects in which sculptors were engaged were exclusively sculptural, a number included both paintings and sculptures and engendered comparisons and competition between the sister arts. This was certainly the case with the Cappella Paolina in S. Maria Maggiore, in which a team of painters (the Cavalier d’Arpino, Ludovico Cigoli, Giovanni Baglione, and Guido Reni) worked side by side with the even larger team of sculptors listed above. The juxtaposition of works by the leading painters and sculptors of the day incited debate about the relative merits of the arts—the paragone—not only among the artists but among critics and connoisseurs. The most extensive and provocative commentary to come out of this debate, however, was a letter of June 26, 1612, written by Galileo Galilei to his close friend Cigoli, most likely in response to a request from the painter to consider the matter from his own perspective. Galileo’s letter, which has assumed canonical status in the paragone literature, articulated his belief that painting is the superior art. Drawing on many of the points made by Leonardo da Vinci in his Trattato and by sixteenth-century writers on the subject, Galileo also presented important new perspectives on the debate, especially on the issue of rilievo (relief) and art’s ability to imitate nature and deceive the eye.

We introduce the debates engendered by the Pauline Chapel decorations because art-theoretical issues, including the paragone, were very much alive in seventeenth-century Rome. Theory informed—sometimes indirectly, other times directly—the works of painters and sculptors alike, and was a central concern of certain influential writers throughout the century. Among these were Federico Zuccari, in his L’Idea de’pittori, scultori et architetti of 1607, Giovanni Battista Agucchi, in his Trattato della Pittura of ca. 1607–15, Vincenzo Giustiniani in his “Discorso sopra la scultura” of ca. 1627, Giovanni Domenico Ottonelli and Pietro Berrettini (da Cortona) in their Trattato della pittura e scultura, uso et abuso loro of 1652, and Giovan Pietro Bellori in his Vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti moderni of 1672, in which he included his essay on the Idea (the ideal in art) as the book’s preface. Significantly, Bellori first presented his discussion on the Idea as a lecture to the Accademia di San Luca in 1664, the institution that provided the most significant forum for theoretical discussion as well as for the practical training of artists.

From the time of its first official meeting in 1593, the Accademia di San Luca welcomed sculptors into its ranks. In addition to being members, sculptors could also serve as instructors and officers. Although painters dominated the position of principe (prince or director) throughout the Accademia’s history, in 1599 Flaminio Vacca was elected to this position, the first sculptor to hold the rank, and he was followed in the seventeenth century by Pompeo Ferrucci (1622), Gianlorenzo Bernini (1630), Francesco Mochi (1633), Alessandro Algardi (1639), Nicolò Menghini (1643), Gaspare Morone (1661), Orfeo Boselli (1667), and Domenico Guidi (1669), after which no other sculptor held the position until Camillo Rusconi in 1727. If sculptors took second place to painters as directors, they nevertheless were elected into this position in relative proportion to their numbers (1:5), and they played an important role in the Accademia’s activities, as in 1594, for example, when Flaminio Vacca, Pietro Paolo Olivieri, Giovanni Battista della Porta, and Giovanni Antonio Paracca il Giovane were invited to make formal presentations to the academy’s members on practical and theoretical aspects of sculpture. The Accademia di San Luca was, in short, a vital institution for sculptors in the early modern period, and it served to elevate their professional status, provide a forum for engaging in theoretical debates, and establish them as equals to painters.

In the present volume, Peter Lukehart’s essay on “The ‘Accademia dei Scultori’ in Late Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Rome” reconstructs a previously unknown portion of this story, showing how the scultori sought—from the foundation of the Accademia di San Luca through the 1660s—to improve their status in the academy by freeing themselves from the persistent medieval structure of Rome’s guild system. Another part of this same story has to do with the activity of the sculptor Orfeo Boselli, whose treatise Osservationi della scoltura antica, probably written in the early 1660s but published much later, seems aimed at demonstrating the theoretical basis and thus the nobility of the art of sculpture. Indeed, Boselli’s precepts dovetail with the art-theoretical and critical discourse encountered in the works of his fellow academicians Bellori and Passeri, also dating to the mid-seventeenth century, but his aim of demonstrating the integration of theory and practice specifically as applies to the art of sculpture was perhaps the most important speculative intervention of the period. In her essay in the present volume, “Orfeo Boselli’s Osservationi della scoltura antica: A Seventeenth-Century Treatise on Sculpture, Its Purpose, and Its Descent into Obscurity,” Maria Cristina Fortunati adds new precision to our understanding of the personal and professional motives behind Boselli’s project, and explains why this important treatise never came to be published in its own time.

Much of Boselli’s treatise is structured by the humanistic project of a dialogue with the antique, in this instance a dialogue rooted in the imitation of the best ancient sculptural models. The study of ancient sculpture was in fact central to the seventeenth-century conception of an “academic” education in art, not only in Rome but, increasingly, throughout Europe. In 1650, when the great Spanish painter Diego Velázquez came to Rome during an extended Italian journey, he ordered numerous casts after ancient Roman statues, which may have been part of an ongoing scheme to found a permanent art academy at Madrid, on the Italian model. Among the many sculptors involved in the production of the copies was Giuliano Finelli, Alessandro Algardi’s most gifted assistant. The casts were completed and shipped to Spain between 1651 and 1653, a remarkable feat considering the difficulty and expense of the task. Although there is no evidence to document their use in the formal academic training of artists, at least not in the later seventeenth century, we do know that about a century later they were put precisely to that educational purpose in the Academia de San Fernando, Madrid, founded by Fernando VI in 1752. Likewise, when the great Gianlorenzo Bernini visited the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris, in 1665, he strongly recommended that the academy should likewise acquire casts of the best antique statues. Referring to the benefits of his own youthful studies after the antique, he observed that the practice of drawing after ancient statuary was, for the beginning student, even more important than the direct study of nature, speeding the process through which the student might conceive “l’idée sur le beau,” that is, the “idea of beauty” essential to the classicist strain of seventeenth-century aesthetics. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the episode, recounted by Bernini’s escort, Paul Fréart de Chantelou, is the very fact that the academy—then in existence for seventeen years—did not yet have such a collection of statuary.

Finally, in addition to being a major locus for the formation of art-theoretical debates and academic-pedagogical methods, Rome was also a center—a laboratory—for artistic experimentation of many kinds that virtually transformed the art of sculpture, both formally and thematically, and had profound implications for the ways viewers experienced works of art. Through experimentation with size and scale, for example, sculptors challenged the very conception of the colossal statue. Michael Cole’s essay on Francesco Mochi’s Santa Marta deals precisely with the perceptual conditions within which seventeenth-century beholders made judgments about “size” (grandezza)—and the novel manner in which the artist manipulated those conditions—proceeding from some insightful observations by the early biographer Passeri. Efforts were also made to break down the traditional divisions between the arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture—what Bernini’s biographers termed the bel composto—and to revive old or invent new sculptural types. Sculptors explored different styles, modes of presentation, and themes, borrowing from and reinterpreting the ancient and early Christian past. This modal approach is brilliantly illustrated in Estelle Lingo’s essay “Impossible Apostles: Francesco Mochi’s Saint Peter and Saint Paul for S. Paolo fuori le mura,” in which the author reveals how the sculptor Mochi used long-misunderstood stylistic distortions to evoke the character of early Christianity in the sacred context of Saint Paul’s burial place. Likewise, seventeenth-century sculptors, in their never-ending quest for novità (novelty), created works that attempted to dissolve the clear boundary that had hitherto separated sculpture’s two primary genres: sculpture in the round and relief. Steven F. Ostrow’s essay “‘Appearing to be what they are not’: Bernini’s Reliefs in Theory and Practice” offers a critical autopsy of this same phenomenon, showing how Bernini consciously confounded the expectations of beholders by creating a kind of sculpture that defies that age-old generic binary.

While the academies of later Renaissance Bologna and Florence became major engines of innovation in the art of painting, Rome was the unchallenged epicenter of art-theoretical developments in sculpture. It must be noted, however, that in the latter half of the seventeenth century Rome ultimately ceded its place to Paris as the center of both theory and sculptural production. This was especially the case after the consolidation of power and cultural hegemony under Louis XIV and Jean-Baptiste Colbert, his minister of finance and Surintendent des bâtiments, and the founding of the French Academy in Rome in 1666. As noted earlier, an increasing number of French sculptors went to the papal capital after the academy’s creation; but the majority of them returned to Paris, creating a virtual renaissance in the art of sculpture in France. As though in direct response to Bernini’s advice, sculptural works—including copies and casts after Rome’s antiquities—produced by French sculptors at the French Academy in Rome were now shipped back to Paris at an unprecedented rate, and further impetus to Paris’s emergence as the new sculptural capital was given by Louis XIV’s acquisition and importation of a number of the most prized ancient statues from Rome. Another indicator of France’s new cultural supremacy is the fact that Bellori, one of the leading cultural figures in Rome, dedicated his Vite of 1672 to Colbert, and to publish his text the author relied on the support of Charles Errard (1606/9–1689), the director of the French Academy in Rome and a founding member of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, of which Bellori was made an honorary member in 1689. Upon the suggestion of Domenico Guidi, who had special relationships with French artists in Rome and the French court, Errard was elected principe of the Accademia di San Luca in 1672, and in 1676, again upon Guidi’s urging, Charles Le Brun, then director of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, was elected principe of the Accademia. And as Rome witnessed a precipitous decline in the number of theoretical texts dealing with sculpture, in Paris discussions concerned with the theory and practice of sculpture—both ancient and modern—proliferated in both published texts and conférences delivered at the Royal Academy by Michel Anguier, Gérard Audran, André Félibien, Charles Perrault, Henri Testelin, Pierre Cureau de la Chambre, François Lemée, Pierre Rainssart, and many others. While a good portion of the French theoretical discourse was based on earlier Italian publications, much of it was also original, marking the end of Italian dominance in the field of sculptural theory. The essays of Julia K. Dabbs (“‘Humoring’ the Antique: Michel Anguier and the Physiological Interpretation of Antique Greek Sculpture”) and Aline Magnien (“On Causes and Effects: Imitating Nature in Seventeenth-Century Sculpture Between Rome and Paris”) demonstrate how Anguier—a figure of crucial but rarely adequately acknowledged importance in this process—simultaneously appropriated and transformed the art-theoretical concepts he gathered through his studies in Italy, making them his own while also recasting them as somehow pertaining to an exclusively French art-theoretical context. By the turn of the eighteenth century, Paris had truly become the new sculptural capital of Europe, not only in terms of practice, but also in terms of art-theoretical speculation.

As in the study of early modern painting, the historical criticism of seventeenth-century sculpture, both Italian and French, has been increasingly informed by an awareness of the implications of seventeenth-century art-theoretical principles, particularly as pertains to the relationship between form and content. Beginning with Rensselaer W. Lee’s seminal essay “Ut Pictura Poesis” (1940), which dealt primarily with the theory of painting from Leon Battista Alberti to Charles Le Brun, scholars have been aware of the extent to which early modern theories of imitation and invention impacted not only on the creative processes of both painters and sculptors, but also on the problem of interpreting their works as the visible embodiments of rhetorical or poetical arguments. Bearing in mind the art-theoretical construct that Lee described (which might more properly be called ut poesis pictura), it became possible for the modern art historian to conceive forms of historical criticism that fully recognize the extent to which visible style and literary content were merged in early modern images, both pictorial and sculptural. In the 1970s, David Summers showed, for example, how a sophisticated, historically informed criticism of sculpture could apply humanistic rhetorical and art-theoretical principles in the act of interpretation, specifically demonstrating how Michelangelo’s imitation of an ancient model such as the so-called Torso Belvedere—a classical fragment of enduring fascination for sculptors, through the time of Bernini and beyond—integrated with a reading of antique and Renaissance rhetorical theory, could produce the concept of the contrapposto, that is, a figural posture which in effect functions as a visual analogue of the rhetorical figure of antithesis. The kind of approach taken by Summers is, however, in no wise unique to the interpretation of sixteenth-century sculpture; and indeed, as several of the essays published here may suffice to illustrate, the quest for a perfect union of visible form and “meaning,” implicit in the seventeenth-century theorization of the Idea, remains a major frontier for future interpretative research on the art of sculpture.

Summers’s approach leads logically to the question of how seventeenth-century beholders might have conceptualized the process of interpreting or “reading” the Idea assumed to reside within the three-dimensional image, and thus dovetails with the past thirty years’ inquiry into the problem of reception in the visual arts—a topic extensively addressed in the present volume. Our authors take a contextual approach to the problem of reception, considering how the rhetorical argument informing a given work of sculpture might have been designed, deployed, and interpreted by contemporary beholders within a well-defined cultural moment. Christina Strunck’s essay “The Poisoned Present: A New Reading of Gianlorenzo Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina” might exemplify this approach, examining the intentionalities structuring Cardinal Scipione Borghese’s commission for Bernini’s famous statue, which we know was ultimately given as a gift to cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. Strunck proposes the possibility that Borghese might not have commissioned this famous work for his own collections (as is usually assumed) but rather might have conceived the commission from the beginning as a gift for Ludovisi—a “poisoned present” designed to communicate a potentially offensive message encoded in Borghese’s choice of subject. Part of the power of this message lay in the exquisite beauty of Bernini’s sculpture, which would have made it impossible for Ludovisi to refuse this gift. Similarly, Anthony Colantuono’s essay concerning François Duquesnoy’s enigmatic relief composition on the theme of the capture of Silenus explores how the sculptor integrated the humanistic technology of iconographic signification with that of affective expression, employing the figure of the “tender” putto in order to induce in the hearts of beholders the sentiment of “tenderness” implicit in the Virgilian text—and thus to render irresistible the moral argument embodied in the invention.

The large, highly sophisticated, and remarkably diverse audience of seventeenth-century Roman patrons and beholders placed unique expressive demands on artists—demands that would have stretched these humanistic figurative technologies to their very limits, thus leading to constant experimentation and innovation. In seventeenth-century Rome, this vast beholding public would have been conditioned, too, by an especially acute awareness of the religious predicament of the time. Damian Dombrowski’s essay “The Sculptural Altarpiece and Its Vicissitudes in the Roman Church Interior” studies how the seventeenth-century resurgence of the sculptural altarpiece relates not only to prior anxieties regarding the dangers of idolatry but also to post-Tridentine technologies for the psychological/emotional “activation” of the Roman Catholic church interior—a process aimed precisely at moving beholders to overwhelmingly powerful religious sentiment. Likewise, Maarten Delbeke’s essay on Alessandro Algardi’s Beheading of Saint Paul and the “theatricality of martyrdom” directly addresses the novel manner in which Seicento Roman sculptors sought to control the beholder’s optical and psychological experience in the service of a newly energized Church.

As is well understood, the brilliant efflorescence of Roman Baroque sculpture was fueled by the unique historical, political, archaeological, and cultural conditions of the papal capital, by constant demands for iconographic novelty and expressive innovation, and by the presence of an exceptionally active art-theoretical culture. As a topic of art-historical study, Roman Baroque sculpture has also generated an extraordinarily rich history of modern scholarship. In order to situate the contributions of our authors in relationship to this scholarly tradition and to help define what is new in their work, it is useful to review the literature on seventeenth-century sculpture in some depth.

The Historiography of Early Modern Roman Sculpture: A Brief Overview

Given the long historical bias that favored painting over sculpture, it is not surprising that the literature on early modern sculpture in Rome is not nearly as rich as that on painting of the period (which, in this volume, we are confining to the period from ca. 1580 to 1680). Our subject—generally designated Roman “Baroque” sculpture—nevertheless has received considerable scholarly attention. But if we exclude seventeenth-century Vite by Giovanni Baglione, Giovan Pietro Bellori, and Giovanni Battista Passeri, the two stand-alone biographies of Bernini by Filippo Baldinucci and the sculptor’s son Domenico, as well as theoretical texts that deal with sculpture, such as Gian Andrea Borboni’s Delle Statue of 1661 and Orfeo Boselli’s Osservationi della scoltura antica, which was written ca. 1661 (but published much later), we need to turn to the very late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to find sustained and serious discussions of early modern Roman sculpture.

Among the very first scholars to treat the subject in more than a cursory way was Francesco Milizia, a principal exponent of Neoclassicism and close follower of Johann Joachim Winckelmann. In his Dizionario delle Belle Arti del Disegno, first published in 1797, he articulated the classicist view that the “Baroque” represented “the superlative of the bizarre, the excess of the ridiculous,” a style that was nothing short of a “plague on taste.” Although Milizia did not offer a broad historical survey of sculpture in the period, in his long entry on “scultura” he discussed a number of sculptors who worked in Rome in the seventeenth century: Duquesnoy, Bernini, Algardi, Michel Anguier, Antonio Raggi, Domenico Guidi, and François Girardon, providing salient biographical information and a critique of some of their works. While praising Duquesnoy’s Santa Susanna and Saint Andrew, he criticized the works by all the other sculptors, saving his harshest comments for Bernini. Milizia acknowledged that Bernini had a “lively and quick” mind and an “ease of conception and execution,” but saw his sculpture as lacking “prudence and purity,” viewing Bernini as “the first to introduce license and errors under the pretense of grace.” Perhaps most egregious among his errors, according to the author, was the fact that “in order to be original” Bernini “paid no regard to the antique . . . [and] renounced that beautiful simplicity” found in the works of the classical past.

Milizia’s treatment of Baroque sculpture took the form of a vehement classicist critique. The same can be said of Leopoldo Cicognara in his Storia della Scultura dal suo Risorgimento in Italia fino al secolo di Canova, the first edition of which was published from 1813 to 1818. Like Milizia, Cicognara viewed “Baroque” art as a “corruption of taste,” castigating sculptors of the period for neglecting the “beautiful works of antiquity.” He deplored Roman Baroque sculptors’ obsession with “novelty” and their shunning of “simplicity”—the basis, in his view, of true beauty. But for as much as Cicognara aligned with his predecessor’s critique, he differed in two distinct ways: he found merit in at least some of the works of Bernini, Algardi, Duquesnoy, and other Seicento sculptors, and he offered a broad historical overview of sculpture in Rome from the pontificate of Sixtus V through the end of the seventeenth century. In Cicognara’s text we encounter Prospero Bresciano, Giacomo del Duca, Taddeo Landini, Niccolò Pippi, Egidio della Riviera, Giovanni Antonio da Paracca il Vecchio, and Leonardo Sormani as representatives of the age of Sixtus. Among the sculptors who worked during the papacy of Paul V, we encounter Camillo Mariani, Silla Longhi, Nicolas Cordier, Paolo Sanquirico, Ambrogio Bonvicino, Ippolito Buzio, Stefano Maderno, Pietro Paolo Olivieri, Cope Fiammingo, Guillaume Berthelot, and Pompeo Ferrucci. His source on these sculptors, although not cited, was most likely Baglione’s Vite, but in contrast to the biographer Cicognara placed these artists in their historical context; not surprisingly, he also passed judgment on their talents—and found virtually all of them to be mediocre. Bernini, Algardi, and Duquesnoy are, for Cicognara, the dominant sculptors of the seventeenth century. Like Milizia, he saved his highest praise for Duquesnoy, whom he saw as the most classical and, thus, the most meritorious sculptor of the century, and, like Milizia, Cicognara viewed Bernini as the ultimate corruptor of taste, writing, “among the three great sculptors that Rome saw work in the seventeenth century the one who contributed most to the decadence of art was Bernini.” Cicognara’s discussion of Seicento sculpture in Rome was not limited to those three most prominent sculptors, however. He also included brief considerations of Ercole Ferrata, Melchiorre Cafà, Giuseppe Mazzuoli, Antonio Raggi, Giuliano Finelli, Andrea Bolgi, Francesco Baratta, Jacopo Antonio Fancelli, Lazzaro Morelli, Leonardo Retti, Filippo Carcani, Francesco Mochi, and Paolo Naldini. What we find in Cicognara’s Storia della Scultura is, quite simply, the most comprehensive discussion of early modern Roman sculpture before the mid-twentieth century.

It was not until the early twentieth century, when literature on early modern Roman sculpture began to proliferate, that the classicist bias against Baroque art was finally abandoned. A. E. Brinckmann devoted several chapters to the subject in his Barockskulptur: Entwicklungsgeschichte der Skulptur in den romanischen und germanischen Ländern seit Michelangelo bis zum 18. Jahrhundert of 1919. Informed by Heinrich Wölfflin’s formalist dichotomy between the Renaissance and Baroque, Brinckmann’s discussion is primary concerned with style—with sculpture’s progression towards a painterly effect. He attended to the sculptors who worked for Sixtus V and Paul V, but devoted most of his attention to what he dubbed the “High Baroque,” applying his Wölfflinian approach to the works of Bernini, Algardi, and Duquesnoy. In his Barock-Bozzetti of 1923–34, Brinckmann turned to a consideration of the terracotta sketch model, both as part of the preparatory process and as what he considered to be the purest expression of a sculptor’s conception. Approximately one and one-half of the four volumes of this study are devoted to Italian Baroque sculptors, in which bozzetti by Stefano Maderno, Mochi, Duquesnoy, Algardi, Ferrata, Guidi, Raggi, Carcani, Francesco Cavallini, and, especially, Bernini are discussed and reproduced. Barock-Bozzetti is the foundational text for research on the topic and still a valuable source.

In a series of articles by Antonio Muñoz published between 1916 and 1918, Roman Baroque sculpture became the exclusive focus. The first, “La scultura barocca a Roma: Caratteristiche generali,” attempts to define—as the title indicates—general formal and conceptual characteristics of Seicento Roman sculpture. In “La scultura barocca e l’antico,” Muñoz surveyed Roman Baroque sculptors’ engagement with the antique, with special emphasis on their restorations of ancient statuary. In the remaining essays, “La scultura barocca a Roma: Iconografia—Rapporti col teatro,” “La scultura barocca a Roma: L’esotismo,” “La scultura barocca a Roma: Le statue onorarie,” and “La scultura barocca a Roma: Le tombe papali,” Muñoz addressed aspects of the iconography (the relationship to theater and its sometimes “exotic” subjects) and typology (honorific statues and papal tombs) of Roman Baroque sculpture—two areas of research (iconography and typology) that are still of central importance to the field.

Since the 1920s, a number of surveys of early modern Italian sculpture have appeared, including Georg Sobotka’s Die Bildhauerei der Barockzeit (1927), Giuseppe Delogu’s La scultura italiana del Seicento e del Settecento (1932), Alberto Riccoboni’s Roma nell’arte: La scultura nell’evo moderno dal Quattrocento ad oggi (1942), Italo Faldi’s La scultura barocca in Italia (1958), John Pope-Hennessy’s Italian High Renaissance and Baroque Sculpture (1963, with subsequent editions in 1970, 1986, and 1996), Valentino Martinelli’s Scultura italiana dal manierismo al rococò (1968), Antonia Nava Cellini’s La scultura del Seicento (1982), and Bruce Boucher’s Italian Baroque Sculpture (1998). Given the scope of each of these books, Roman sculpture from ca. 1580 to 1680 figures only as a part of their broader surveys, but each provides a useful compilation of information on some of the sculptors active in Rome during this period, as well as illustrations of a small selection of their works. It must be said that all of these authors were primarily interested in style and typology, thus offering little in the way of new perspectives on the material. The most recent survey by Alessandro Angelini, La scultura del Seicento a Roma (2005), is a more focused study than those that preceded it, in that it looks exclusively at Roman sculpture of the seventeenth century. Although largely a synthesis of previously published scholarship, it organizes the material in some new ways, with chapters on Lombard, Tuscan, and French sculptors in Rome, the “neo-Venetian tendency” in Roman Baroque sculpture, the bel composto, Barberini patronage of sculpture, and “masters and pupils.” The emphasis on style and typology is also found in the more specialized studies of Roman sculpture of the late Cinquecento and early Seicento, such as Anton Bergmann’s Die römische Plastik in der Zeit der Pontifikate Gregors XIII. bis Clemens VIII. (1572–1605): Ein Beitrag zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Skulptur von der Spätrenaissance zum Barock (1930), Adolfo Venturi’s Storia dell’arte italiana: La scultura del Cinquecento (1937), and Catherine E. Fruhan’s “Trends in Roman Sculpture circa 1600” (1986). Exceptions are Sylvia Pressouyre’s important article of 1975, “Sur la sculpture à Rome autour de 1600,” with its brief but far-reaching examination of sculptural practice, styles, and patronage in Rome at the turn of the seventeenth century, and Alexandra Herz’s 1974 doctoral dissertation, “The Sixtine and Pauline Tombs in Santa Maria Maggiore: An Iconographical Study,” in which she offers a contextual and iconographical reading of the reliefs on the papal tombs in the Sistine and Pauline Chapels.

Rudolf Wittkower’s Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600–1750 (first published in 1958, but with several later editions), although an even broader survey than those cited above, deserves special mention for the breadth and depth of its discussion of early modern Roman sculpture. Notwithstanding Wittkower’s facile dismissal of the work of most of the sculptors that preceded Bernini, and his emphasis on Stilgeschichte (the history of style), his survey provides a broad and nuanced consideration of sculptural production in Rome from ca. 1585 through the end of the seventeenth century. For as much as he was concerned with individual sculptors and their styles, one of his most significant contributions was to never lose sight of the larger cultural-historical context, providing vital information on the social and political situation in Rome, patrons of sculpture (both private and ecclesiastical), new iconographies, art theory, and the influence of the Church. As one of the founding fathers of Bernini studies, Wittkower naturally devoted a long chapter to him, which addresses his sculpture, painting, and architecture; but he also did justice to Algardi and Duquesnoy, and paid considerable attention to many other sculptors, including Finelli, Bolgi, Cafà, Ferrata, Raggi, Guidi, and dozens more, charting, especially, the ongoing influence of Bernini until the end of the seventeenth century. The text remains an invaluable classic, especially in its most recent revised form, which no student or scholar of the period can ignore.

A number of early modern Rome’s sculptors also have been the subject of monographic studies, which have appeared in articles, books, and doctoral dissertations. While the articles are far too numerous to list, some of the foundational books and dissertations on individual sculptors must be mentioned. It should come as no surprise that there are more monographs on Bernini than on any other artist. Among them are Stanislao Fraschetti’s Il Bernini (1900), Wittkower’s Gian Lorenzo Bernini: Sculptor of the Roman Baroque (1955, with two later editions), Howard Hibbard’s Bernini (1965), Hans Kauffmann’s Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini: Die figürlichen Kompositionen (1970, which is primarily concerned with iconography), and Charles Avery’s Bernini: Genius of the Baroque (1997). On Algardi, we have Minna Heimbürger Ravalli’s Alessandro Algardi scultore (1973) and, the definitive monograph, Jennifer Montagu’s Alessandro Algardi (1985). Mariette Fransolet’s François du Quesnoy, sculpteur d’Urbain VIII, 1597–1643 (1942) was the first comprehensive monographic study devoted to the Flemish sculptor, which has now been superseded by Marion Boudon-Machuel’s François du Quesnoy: 1597–1643 (2005) and Estelle Lingo’s François Duquesnoy and the Greek Ideal (2007). Moving beyond the three dominant sculptors of the century, monographs (and monographic dissertations) on other major figures of the period include (in alphabetical order of the artists’ names) Hans-Ulrich Kessler’s Pietro Bernini (1562–1629) (2005); Barry Harwood’s dissertation, “Nicolo Cordieri: His Activity in Rome 1592–1612” (1979), and Sylvia Pressouyre’s Nicolas Cordier: Recherches sur la sculpture à Rome autour de 1600 (1984); Jessica Marie Boehman’s dissertation, “Maestro Ercole Ferrata” (2009); Damian Dombrowski’s Giuliano Finelli: Bildhauer zwischen Neapel und Rom (1997); David Bershad’s dissertation, “Domenico Guidi: A 17th Century Roman Sculptor” (1971), and Cristiano Giometti’s Domenico Guidi 1625–1701: Uno scultore barocco di fama europea (2010); Agnese Donati’s Stefano Maderno scultore: 1576–1636 (1945); Roger C. Burns’s dissertation, “Camillo Mariani: Catalyst of the Roman Baroque” (1980), and Maria Teresa De Lotto’s “Camillo Mariani (1567–1611): Catalogo ragionato delle opere” (2006); Meinolf Siemer’s dissertation, “Francesco Mochi (1580–1654): Beitrage zu einer Monographie” (1981) and Marcella Favero’s Francesco Mochi: Una carriera di scultore (2008); and Robert H. Westin’s dissertation, “Antonio Raggi: A Documentary and Stylistic Investigation of His Life, Work, and Significance in Seventeenth-Century Roman Baroque Sculpture” (1978). Notwithstanding the monographic studies we have (unintentionally) overlooked, the foregoing list is remarkably short, underscoring just how much basic work remains to be done on many of early modern Rome’s sculptors.

It goes without saying that one of the major contributions of monographic studies—what makes them fundamental to future research—is the establishment of the sculptors’ oeuvres, usually based upon extensive archival research. Archival research is not, however, the exclusive domain of the monograph writer, and, in fact, there is a long history of publications that focus on presenting documents—essential source material for research on early modern Roman sculpture. In a series of volumes that appeared between 1877 and 1886, Antonino Bertolotti made available documents concerning Subalpine (Piedmontese), Sicilian, Flemish and Dutch, Modenese, Parmese, Tuscan, Bolognese, Ferrarese, French, Swiss, and Lombard artists who worked in Rome in the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries. Although his transcriptions of documents are often partial and, in some cases, incorrect, these volumes contain a wealth of information drawn from Roman archives about the activities of sculptors from diverse regions who worked in Rome. More focused archival-based publications include Johannes A. F. Orbaan’s Documenti sul barocco in Roma (1920), which offers a wide spectrum of documents dealing with Rome in the early Seicento, many of which concern sculpture; Oskar Pollak’s Die Kunsttätigkeit unter Urban VIII (1928–31), which, as its title clearly indicates, deals with artists, many of them sculptors, active during the papacy of Urban VIII (r. 1623–44); Vincenzo Golzio’s Documenti artistici sul Seicento nell’archivio Chigi (1939), which includes much documentary material on sculptors employed by Alexander VII Chigi (r. 1655–67) and members of his family; Jörg Garms’s Quellen aus dem Archiv Doria-Pamphilj zur Kunsttätigkeit in Rom unter Innocent X (1972), which documents the patronage of the Pamphilj family (the family of Innocent X, who reigned as pope from 1644 to 1655) and illuminates the careers of several sculptors; Minna Heimburger Ravalli’s Architettura scultura e arti minori nel barocco italiano: Ricerche nell’archivio Spada (1977), a study rich in information about sculptural activity drawn from documents found in the archive of the Spada (a family of Seicento churchmen and art patrons), which also formed the basis of Klaus Güthlein’s “Quellen aus dem Familienarchiv Spada zum römischen Barock” (1979 and 1981); Marilyn Aronberg Lavin’s Seventeenth-Century Barberini Documents and Inventories of Art (1975), another very rich source of archival material on sculptors employed by the Barberini family; Anna Maria Corbo’s Fonti per la storia artistica romana al tempo di Clemente VIII (1975) and Corbo and Massimo Pomponi’s Fonti per la storia artistica romana al tempo di Paolo V (1995), in which sculptors active during Clement VIII and Paul V’s papacies figure prominently.

While a survey of the literature on early modern Roman sculpture should also include catalogues of museum collections and exhibition catalogues, like monographic articles they are far too numerous to list. Instead, let us turn to a final group of publications that have made major contributions to the field. The first is Jennifer Montagu’s Roman Baroque Sculpture: The Industry of Art, which appeared in 1989 and which is cited here (in the notes) several times. The culmination of years of study, including endless hours in the archives, this book, perhaps more than any other publication, introduced several new areas of research. Rather than focusing on individual sculptors or questions of style, iconography, or typology, Montagu’s primary area of inquiry concerns how sculpture was produced in Baroque Rome, from its conception, through its execution, to its installation. Through a series of case studies, she addresses, among other subjects, the sources of marble used for statuary, workshop practices, the making of sculptural models, the relationship between and varied roles of sculptors and founders, the collaboration between sculptors, architects, and painters, the restoration of antique sculpture, and the production of ephemeral sculpture. She presents, on virtually every page, new information about and insights on some of the best-known works of the Roman Baroque as well as on works rarely given more than passing notice, if any, such as sugar sculptures (trionfi), papier-maché festival “machines,” bronze candlesticks, and chapel grilles. All of early modern Rome’s major sculptors make an appearance in this volume, but so too do dozens of less famous sculptors, many known only through documents. The book represents a milestone in the literature, which has dramatically enriched our understanding of how sculpture was made.

Another major contribution to the study of early modern Roman sculpture is Montagu’s Gold, Silver, and Bronze: Metal Sculpture of the Roman Baroque of 1996, a book that is very much a sequel to her Roman Baroque Sculpture. Here, again, her focus is on the production of sculpture—on the activity in the workshops, the complex collaborations among the artists who produced the drawings, the models, and the molds and then cast and finished the works, and the interaction between artists and patrons. In contrast to most studies of Roman Baroque sculpture, which concentrate on marbles and large-scale bronzes, this book looks primarily at small works in bronze, silver, and gold, such as tabernacles of the sacrament, medals, braziers, candlesticks, mirror frames, ecclesiastical maces, plates, ewers, reliquaries, and much more. As did her earlier study, this is a book that makes use of a wealth of new documents and drawings, considers both well-known and obscure artists, discusses major patrons, and illuminates an important but little-studied aspect of sculptural production. What emerges from the pages of this study is a far richer understanding of sculptural production in Rome, and a realization that the so-called minor arts were an integral part of it.

Very different than Montagu’s two books in their approach and scope, but equally indispensable to the study of early modern Roman sculpture, are Andrea Bacchi and Susanna Zanuso’s Scultura del ’600 a Roma of 1996 and Oreste Ferrari and Serenita Papaldo’s Le sculture del Seicento a Roma of 1999. The first of the two, a tome of 862 pages, is the first comprehensive “catalogue” of sculptors who are documented as having worked in Rome in the seventeenth century. Primarily a book of photographs, which number 759, it presents selected works of one hundred sculptors, some Frenchmen and Flemings but the majority of them Italians. The images are followed by biographical entries, which include a chronological list of major works and a succinct bibliography on each of the sculptors. Systematic if not exhaustive (omitted from consideration are ephemeral works, wood sculpture, medals and medalists, and many “minor” sculptors), it is nevertheless a fundamental source, a necessary starting point for any study of Roman Baroque sculpture. Ferrari and Papaldo’s volume is in many ways a complement to Bacchi and Zanuso’s. Also a massive tome (with 661 pages and more than 600 illustrations), it is systematically arranged according to the location of sculptural works—churches and other ecclesiastical buildings; palaces, villas, piazzas, and bridges; museums and galleries; private collections; and the Vatican complex. Nearly comprehensive in its coverage, the book includes many anonymous sculptures and offers discussions of each work along with bibliographies. The introduction by Ferrari is particularly valuable, as it surveys the art-theoretical, biographical, and guidebook literature of the seventeenth century in Rome, discusses Roman Baroque sculptors’ engagement with the antique (including restorations), and outlines the major functions and typologies of sculpture (with a particular emphasis on funerary monuments). It is a wide-ranging study of Roman seventeenth-century sculpture, a key source for every student or scholar interested in the subject.

The final publication in our review of the literature is Torgil Magnuson’s two-volume Rome in the Age of Bernini (1982 and 1986). Although, as the author states, it is based entirely on published research, it is also intended as a panoramic history of Rome from 1585 to 1689, painting a vivid picture of the city’s social, political, cultural, and artistic life. Like Ludwig von Pastor before him, Magnuson organized his history by pontificates: volume 1 spans those from Sixtus V through Urban VIII; volume 2, from Innocent X through Innocent XI. The book offers a wealth of information on the individual popes and their families, papal foreign and domestic policies, the religious and social landscape, and Rome’s economy and cultural life, including musical, operatic, and theatrical performances. However, painting, sculpture, architecture, and urban planning are the ongoing focus and the book’s true subject. As many of the major projects carried out over the century are discussed, sculptors and sculpture figure prominently. Perhaps the greatest contribution Magnuson makes to the study of early modern sculpture—and Roman Baroque art more generally—is its rich contextualization within the fabric of Rome’s social and cultural history.

As we hope this survey has demonstrated, much ground has been covered in the field of early modern sculpture in Rome; and much remains to be explored. The field lacks the equivalent of Francis Haskell’s Patrons and Painters: Art and Society in Baroque Italy (1963), with its sweeping discussion of Seicento Roman painters and their patrons. Even so, the field has by now moved well beyond Haskell’s half-century-old models of patronage and collecting as ends in themselves, addressing a more instrumental approach that integrates the question of patronal intentionality with that of the iconographic and functional interpretation of the art object itself—a new approach that has emerged mainly in the reading of works commissioned and deployed in diplomatic and political contexts.

Notwithstanding Jennifer Montagu’s contributions to our knowledge about the production or “industry” of art, missing, too, are publications on sculpture paralleling such works as Patrizia Cavazzini’s Painting as Business in Early Seventeenth-Century Rome (2008) and Richard Spear and Philip Sohm’s Painting for Profit: The Economic Lives of Seventeenth-Century Painters (2010), which have done so much to expand the parameters of research on Baroque painting by examining the nitty-gritty economic realities of painters’ lives and the art market. There is still much to be done in the areas of art theory and sculpture, on the political capital of sculpture, and on the relationships and collaborations between sculptors and painters in the period. And, as noted above, basic research remains to be done on many of the sculptors active in Rome during the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as more interpretative studies on specific aspects of their work.

It is our hope that the essays in this volume, which offer critical perspectives on the place of sculptors in the Accademia di San Luca, the relationship between art and nature, the influence and impact of the antique, sculptural practice and theory, the reception and interpretation of sculpture, sculpture’s political function, and the ways sculptors experimented with typologies, materials, styles, modes, and subject matter, make a first step toward filling some of the gaps, and that our readers will come away from this volume with a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the richness, vitality, and complexity of early modern Roman sculpture.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.