Beyond the Covenant Chain

The Iroquois and Their Neighbors in Indian North America, 1600–1800

Edited by Daniel K. Richter, and James H. Merrell

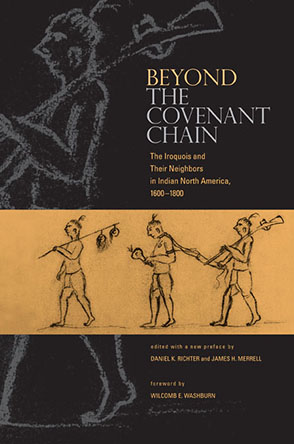

Beyond the Covenant Chain

The Iroquois and Their Neighbors in Indian North America, 1600–1800

Edited by Daniel K. Richter, and James H. Merrell

“A state-of-the-art look at Iroquois relations with other tribes. . . . An excellent example of how an Indian-centered approach to colonial history can contribute to our understanding of the broader world in which all colonial Americans lived.”

- Unlocked

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

An Open Access edition of Beyond the Covenant Chain is available through PSU Press Unlocked. To access this free electronic edition click here. Print editions are also available.

First published in 1987, Beyond the Covenant Chain was one of the first studies to acknowledge fully that the Iroquois never had an empire. It remains the best study of diplomatic and military relations among Native American groups in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century North America.

Published in paperback for the first time, it features a new introduction by Richter and Merrell. Contributors include Douglas W. Boyce, Mary A. Druke-Becker, Richard L. Haan, Francis Jennings, Michael N. McConnell, Theda Perdue, and Neal Salisbury.

“A state-of-the-art look at Iroquois relations with other tribes. . . . An excellent example of how an Indian-centered approach to colonial history can contribute to our understanding of the broader world in which all colonial Americans lived.”

“Beyond the Covenant Chain . . . will prove invaluable to anyone interested in the experiences of one of the most important and complex Indian peoples of colonial North America.”

“A must for serious students of the Iroquois and Indian-white relations in the colonial period.”

“These fine studies of Indian-Indian relations provide a more accurate picture of Iroquois power and presence in native North America and demonstrate that the field of Iroquois history is far from overworked.”

Daniel K. Richter is Professor of History and Director of the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. His most recent book, Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America (2002), won the 2001–2002 Louis Gottschalk Prize in Eighteenth-Century History and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History.

James H. Merrell is Professor of History at Vassar College. His book, The Indians' New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact Through the Era of Removal (1989), won the Bancroft Prize, the Merle Curti Award, and the Frederick Jackson Turner Award. His most recent book is Into the American Woods: Negotiators on the Pennsylvania Frontier (1999).

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Daniel K. Richter and James H. Merrell

Nearly two decades have passed since a conference on "The ‘Imperial’ Iroquois" convened in Williamsburg, Virginia, and most of the essays in this volume first saw the light of day. Because so much in the study of early American history in general and Native American history in particular has changed—and, perhaps more importantly, because so much has remained the same—it is a propitious moment to reissue a work long out of print.

The mid-1980s were an exciting time for those of us who had been trained in the "mainstream" of Anglo-American colonial history. Steeped in the various "new histories" and inspired by still confidently empirical anthropological theory, we were emboldened to see in Native history a new, inclusive way of getting to the heart of the early American experience. (And we did then tend to think of historical experience as more singular than multiple, as the subtitles of early articles each of us published in The William and Mary Quarterly in that pre-postmodern period suggest.)1 "The ‘Imperial’ Iroquois" conference, sponsored by what is now known as the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, seemed a significant institutional acknowledgment of this avenue of inquiry. Our dissertations had successively won us two_year postdoctoral fellowships at the Institute, and, during our time there, we were joined by two senior fellows who were pioneers of the kind of history we aspired to do—and who, truth to tell, struck fear in our callow hearts—W.J. Eccles and Francis Jennings. With the simultaneous presence of James Axtell on the History faculty at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg briefly seemed either the center of a scholarly revolution—or the one place so many eccentrics could safely be quarantined.2 Whatever the case, we were encouraged to organize a conference in order to mark this happy, temporary confluence of scholars working on Native history.

The years since have demonstrated that, if our notions about the place of Indians in early America—and those of other scholars laboring away in other locales, most notably Gary B. Nash—did not quite foment a revolution, at least they no longer seemed peculiar.3 Although each of us has bemoaned in print the glacial pace of the paradigm shift, Native American history has, to a degree neither of us could have imagined when we started out, become more central to writing and teaching about the colonial past.4 Since Beyond the Covenant Chain was first published in 1987, many of the most distinguished works on early America have dealt with Native themes, and their authors (among them several contributors to this volume) include some of the most prominent scholars of this generation. Papers and panels proliferate at professional meetings, graduate students flock to Native American, frontier, and cross-cultural topics, and few historians now would dream of including in the opening paragraphs of a U.S. History survey textbook a description of "a vast and virgin continent, which was so sparsely peopled by Indians that they were to be eliminated or shouldered aside."5

Beyond the Covenant Chain, then, appeared at an important historiographical moment, and deserves a new audience because it so well captures that moment’s strengths and weaknesses, its insights and blind spots. One marker of the moment was the project’s swift conceptual transformation. Initially reflecting an older preoccupation with European images of Indians rather than Indian experiences, early conference planning styled it The Imperial Iroquois—without inverted commas. Then, on second thought, we added the quotation marks to announce that no one seriously believed anymore that there had been an Iroquois empire in the European sense. To further the point, Jennings opened the conference proceedings by bluntly declaring the very term ‘Imperial’ Iroquois a misnomer grounded in Eurocentric myth_making and wishful thinking. In the end, we recast the volume to move "beyond" the Covenant Chain alliance between Iroquois and their (mainly colonial) neighbors, beyond Euro-Americans and Euro-American themes entirely, in order to focus more intently on relationships among Native American peoples.

Even as Beyond the Covenant Chain peered deeper into Indian country, the currents of scholarly inquiry swept on after 1987, finding new channels, yielding new understandings of the confluence and collision of cultures in colonial times.6 With the advantage of hindsight—and insight from a shelf of new books—it can be argued that these essays do not go far enough beyond the Covenant Chain. Treating formal diplomacy and high politics, they have little to say about the spirituality that shaped every aspect of Native life—including diplomacy and politics.7 Assuming that diplomats and politicians were all men, the volume slights both the gendered quality of treaty discourse and the pervasive, if shrouded and subtle, role that women played in negotiations.8 Taking those men too much, perhaps, at face value, these chapters give insufficient attention to the complexity and convolution of identity, the construction and reconstruction of race that, recent works have found, were an important feature of the early American landscape.9 Too hastily rejecting the image of Iroquois empire as mere fictions rather than powerful modes of discourse, some chapters underestimate how shrewdly Native diplomats manipulated Euro_American imperial expectations, and how those imperial expectations themselves shaped both the conceptualization and the reality of relations among Native groups themselves.10

In other ways, however, the volume anticipates recent trends and terms that have come to dominate the scholarly conversation. One is ethnogenesis, the making and remaking of Native nations that went on in response to the disease, displacement, and dispossession visited upon North America after 1500.11 Though the word itself appears nowhere in the pages that follow, the Indian peoples that do occupy center stage—not just Iroquois but also Catawbas and Cherokees, Conestogas and Tuscaroras—were deeply engaged in that very project of demolition and reconstruction, an experience that was as difficult to undergo then as it is to uncover now. More pervasive in recent scholarship is an interpretive metaphor that helps us comprehend the colonial encounter is the middle ground. The term, coined by Richard White more than a decade ago in his brilliant book on the Great Lakes region, encompasses the physical and cultural space between worlds, a place where Natives and newcomers came together to swap goods and forge alliances, to make love and wage war, to find ways past their differences in order to create something new out of "shared meanings and practices." White's focus was on Indian relations with the New France, the British Empire, and finally the United States; those following his lead have also tended to confine their hunt for other middle grounds to the frontier between Indian and European. Yet the essays in this volume implicitly argue that Natives, too, had their middle grounds, arenas where peoples speaking different languages, worshipping different gods, and pursuing different forms of happiness met and mingled, found common ground and forged new ways to get along.12

That abiding fixation on the colonial-Native equation makes this volume more than an historiographical artifact, more than a foreshadowing of topics and themes to come after 1987.13 It makes these pioneering, innovative essays, to a remarkable degree given the span of time since they first appeared, altogether unique. It is almost as if the authors blazed a trail Beyond the Covenant Chain, beyond the preoccupation with European colonial relations with Indians, only to turn around and find that no one was following them. For the most part, these chapters remain the only systematic studies of diplomatic, military, and political relations among eastern North American Native communities in this era. The questions they explore—the nature of political systems, the structure and symbolism of intercultural diplomacy, the reconfiguration of Indian peoples devastated by epidemics and warfare, the adaptability of cultural traditions, the patterns of trade, combat, and migration that structured life across lines of community and culture—are as fresh, as important, and as overlooked today as they were when they were written.

Perhaps one reason for that ongoing obscurity is that scholars generally remain clustered around those places in the colonial American landscape—treaty council grounds, trading posts, military garrisons, missionary stations—where Europeans were, and where the evidential light is best. If nothing else, these essays show that Native ambassadors visited Onondaga, Logstown, and Echota at least as often as they showed up in Philadelphia, Albany, or Charleston, that an Iroquois, a Cherokee, or a Wampanoag spent as much time thinking about Catawbas, Mohawks, or Delawares as about New Yorkers, Pennsylvanians, or Virginians. After 1492, these essays insist, Native Americans did not merely orbit the bright new colonial sun.

In the end, what to us was perhaps the most significant question these essays addressed remains, to a large and disappointing degree, unanswered in the years since this book first appeared: how to find a narrative focus for writing histories of the continent genuinely centered on Native American experiences. "Perhaps," we wrote in the first edition, "future research should shift away from the familiar area of Indian relations with Europeans and towards contacts, conflicts, and connections among the Five Nations and their native neighbors." By making this volume available again, we renew the call. We hope that the far deeper and more subtle understanding scholars now have of Native histories will enable them to move still farther beyond the Covenant Chain, to peer past Iroquoia, in order to explore the character and significance of such contacts, conflicts, and connections wherever they might be found. We are certain that the results of those explorations will once again deepen—indeed, transform—understanding of early America.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.