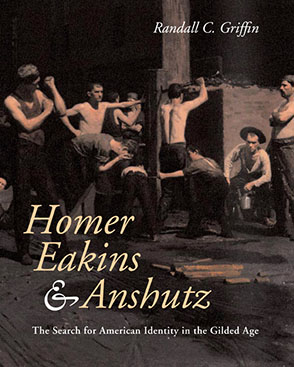

Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz

The Search for American Identity in the Gilded Age

Randall C. Griffin

Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz

The Search for American Identity in the Gilded Age

Randall C. Griffin

“Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz is an important contribution to the field of nineteenth-century American art history. Randall Griffin argues that nationalistic concerns in art led to a perceptible shift in subject matter in painting. The new paintings displayed a remarkably large range of subjects, as evidenced by works as different as Thomas Eakins’s Swimming Hole and Winslow Homer’s beloved Adirondack pictures. As Griffin describes in cogent detail, they all bear on or issue out of the question of how ‘American-ness’ can be construed in relation to the enormous weight of European influence and artistic traditions.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Winner of the 2005 Vasari Award presented by the Dallas Museum of Art for the finest art history book authored by a scholar in Texas

Not only does Griffin trace the interplay of issues of nationalism, class, and gender in American culture, but he also offers insightful readings of key paintings by Eakins and other canonical artists. Further, Griffin shows that by 1900 the nationalist project in art and criticism had helped open the way for the formulation of American modernism.

Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz will be of importance to all those interested in American culture as well as to specialists in art history and art criticism.

“Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz is an important contribution to the field of nineteenth-century American art history. Randall Griffin argues that nationalistic concerns in art led to a perceptible shift in subject matter in painting. The new paintings displayed a remarkably large range of subjects, as evidenced by works as different as Thomas Eakins’s Swimming Hole and Winslow Homer’s beloved Adirondack pictures. As Griffin describes in cogent detail, they all bear on or issue out of the question of how ‘American-ness’ can be construed in relation to the enormous weight of European influence and artistic traditions.”

“Griffin has prepared a rare gem. He combines insightful expert opinion with enough general information so that his book will interest the non-specialist.”

“Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz: The Search for American Identity in the Gilded Age does several things well.”

Randall C. Griffin is Associate Professor of Art History at the Southern Methodist University and the author of the exhibition catalogue, Thomas Anshutz: Artist and Teacher (1994).

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Refashioning "America" in Art

2. Negotiating Identity After the Civil War in the Paintings of Winslow Homer

3. A Burst of Unsettling Imagery

4. Finding the Old World at Home

5. Winslow Homer, Avatar of Americanness

6. When America Became Other in the Adirondack Scenes of Winslow Homer

7. Postscript: A Return to American Themes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

By any measure, American art underwent a major transformation between the end of the Civil War and 1900. Histories of this period locate the source of this change in a rift between the styles of "Old-Guard" painters and the younger, European-trained artists of the time. This conflict was distilled in the famous dispute between the traditionalist National Academy of Design and the progressive Society of American Artists. Although the issue of style played a key role in shaping late nineteenth-century American art, to see this art principally through a formalist lens is to ignore a debate over national identity that cut across lines of style. A constellation of social changes shifted the terms by which national identity could be conceived, while the tidal wave of European art that washed over the country in the decades following the Civil War made American art and criticism particularly enticing territory in which to explore issues of "Americanness." The art and art criticism discussed in this study, which was produced between 1865 and the early twentieth century, thus capture a concern with and a confusion over how to embody what made America distinct.

In the late nineteenth century it became increasingly difficult for American artists—whether they were old-fashioned realists or painters who emulated the newest Parisian styles—to compete at home with established European artists. After the Civil War artists were increasingly bedeviled by shifts in taste that made American painting and sculpture seem provincial. During the war great fortunes were made (in railroads, armaments, and industry), and the nation’s industrial capacity and economy expanded rapidly in the wake of that conflict. The number of millionaires climbed from a handful before the war to about four thousand by 1892. In response to this new wealth and the corruption that accompanied it, Mark Twain coined the satirical phrase "the Gilded Age," which he used as the title for an 1873 novel that offers a stinging political critique of the national culture. For Twain, this was an age of excess, waste, and corruption. Financiers and industrialists like Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Henry Clay Frick built posh, eclectically styled homes in Newport, Rhode Island, and on Fifth Avenue; the social aspirations of these "robber barons" (a term first used in 1880) obliged them to fill these houses with the finest European furniture and works of the "old masters," as well as with art that had won awards at the Paris Salon, the most prestigious exhibition in Europe.

The tastes of the rich, along with those of a growing middle and upper-middle class, sparked rapid changes in American art consumption. In many ways, what constitutes today’s New York art world (with its museums, galleries, auction houses, art magazines, and critics) emerged in nascent form in America in the 1870s, as an outgrowth of the demands of the expanding number of consumers. Granted, there were no Marxist or formalist critics like Clement Greenberg and no radical avant-garde artists like the Abstract Expressionists or the Minimalists. Even so, after the Civil War art first became an important symbol of sophistication for the nation’s nouveau riche, whose needs were served by art dealers like M. Knoedler & Co. and Daniel Cottier, frequent art auctions, and museums, starting with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1870. A host of journals and newspapers offered information about changes in American and European art. America’s elite took their cues from magazines like the Century and Art Journal. To subscribe to one of these journals asserted high social status. Newspapers like the New York Tribune and New York Evening Post also catered to an educated elite. Magazines like Harper’s Monthly and Appleton’s Journal, by contrast, were written for a middle-class readership, although they still included many reviews of art exhibitions. Journals and newspapers such as the Century, American Art Review, the New York Times, The Galaxy, Brush and Pencil, and Scribner’s Monthly offer a treasure trove of primary material about American art and culture. This book departs from much previous scholarship on this period in its reliance on a broad range of art criticism from those and other publications, much of which has not been examined before.

Critics who wrote about art varied considerably in background and taste. Some of the most prominent critics (such as Clarence Cook and William C. Brownell) were well educated and part of the nation’s older upper class. But critics were a diverse lot: they included painters, poets, editors, journalists, and teachers. Some reviewed literature and theater in addition to painting, sculpture, and printmaking. As critics still do today, these men and women helped to shape artists’ reputations. Although critics differed in their support of various kinds of American and European art, most shared the goal of a stronger, eventually independent, native school of art. Critics and artists confronted (or, in some cases, bolstered) the perception, especially widespread among a new upper class in thrall to European culture, that American art was embarrassingly inferior. As the astute critic Charles Caffin wrote about the late nineteenth century:

<ext>

[The] recognition of the superiority of foreign art, which led the painters to go abroad, induced the American public also to ignore the home-made brand. The dealers, scenting larger profits in the imported picture, were not slow to push its merits; a vogue for things foreign was established, and it became as necessary for the rich to have Barbizons, which was well, and many other kinds of foreign pictures. . . . Among the old families it was a sign of correct taste, among the far larger number of quickly-come-to-consequence a passport to gentility.

<end ext>

Such statements explain why most American art collections were dominated by European paintings and sculpture, although there were exceptions. Thomas B. Clark’s collection was one, and collectors like Charles L. Freer bought a mixture of American and foreign art. The wealthy often purchased art while traveling abroad, or through art agents in Europe such as Samuel P. Avery. This bias against native art helps explain why critics frequently wielded traditional negative stereotypes of the Old World in an attempt to undercut the reputation of European art and thus temper the nation’s infatuation with its culture. The French were a favorite target. In 1876 one critic wrote: "No foreign nationality (if we except possibly the German) has shown so low an estimate of the American capacity for judgment in matters of taste, as the French. None has given so prevailing evidence of a disposition to regard our aesthetic aims and criticism as tentative only, and crude and barbarian."

Given the common view that the nation was a cultural backwater, American artists and critics faced the daunting challenge of finding native subjects that patrons would think the equal of those treated in European art. "American identity" was thus not easily pictured in the Gilded Age. It appeared as something mutable, something with permeable boundaries. The efforts of artists and critics to remake American art were often qualified by the necessity of catering to the Eurocentric tastes of elite patrons, which explains why there was a common, self-conscious blurring of the "American" and "European" in art. This made the preservation of a national distinctiveness in American art especially challenging.

Although the origins and effects of nationalism are immensely complicated, I take as a starting point the generally accepted tenet that nationalism—whether spawned by religion, nation-state, or popular movement—is at once an ideology of interconnecting drives that provide a sense of cohesion and self-determination, and a cluster of social practices and institutions that defend a given state’s traditions and interests over others. As Adrian Hastings has argued, the nationalism of our time, and of the era under study here, is driven by imperialist, expansionist ideals, or, conversely, by fears of a loss of identity.

The Gilded Age exemplifies anxiety over the loss of national identity. In the late nineteenth century, the population as a whole and the American art world within it experienced rapid social and economic change. After the cataclysmic upheaval of the Civil War, the country was jolted by a widespread shift of population from farm to city, a surge in immigration, a much-expanded upper class, the closing of the western frontier, two major financial crashes, and a large-scale industrial revolution, which led to the rise of labor unions and bitter, violent strikes. These changes created a divergence between the collectively understood ideals of what America was and uneasy perceptions of what the country was actually becoming. Rapid change made it difficult to define anything as transcendently "American." For artists and critics seeking a distinctively national art, the culture’s apparent lack of cohesive selfhood presented a further challenge: how to construct an aesthetically acceptable, nationally distinct visual imagery to replace that of the outmoded Hudson River School’s portrayals of American wilderness.

The art and criticism examined in this study confirm Benedict Anderson’s argument that national identity is inherently pliable and contingent, continually remolded by historical forces. American selfhood in the late nineteenth century was highly fluid. A panoply of competing "Americas" appeared, as if painters and critics were testing how far the definition of Americanness could be stretched to serve the needs of the art world. This elusiveness is telling and lies at the heart of this study. While most critics shared the view that native subjects were a clear index for the Americanness of art, others, such as John Van Dyke, felt that painters need not render "the New York Stock Exchange, or buffalo-hunts and Indian life on the Western plains" in order to produce intrinsically national imagery. For Van Dyke, what mattered most in determining nationality was the artist’s "individual thoughts and [distinctive] . . . manner of expressing them." As another critic argued, "What we need is men who do not follow in the track of others." If some equated individuality and artistic autonomy with Americanness, others thought "indisputable Americanism" synonymous with simplicity, directness, and truthfulness to nature. The works of many artists, including Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins, were lauded as exemplifying these characteristics. In addition, critics wrote glowingly throughout this period about artists’ American "habits of industry" and manliness. In sum, there was never a consensus on what was innately American about the nation’s art or artists, but much was written concerning the desirability of an American art.

Some critics feared that the nation’s art would be denuded of anything intrinsically its own by slavish imitation of European works. They did not want the emerging national art to be forever beholden to European models, perpetually validated from without. Yet their project—to separate American art from European—was fraught with difficulties. Given American artists’ debt to French, English, German, and Italian models, attempts to make clear-cut divisions between American and European art were generally spurious, and often laced with contradiction.

Perhaps the major reason that scholars have until recently paid so little attention to late nineteenth-century nationalist criticism is that, starting in the 1960s, historians of American art reacted against the isolationist/nationalist thinking that had dominated the art discourse of the 1920s through the 1950s. This rejection of nationalist views led scholars and critics to celebrate such overtly European-inspired artists as William Merritt Chase and Edmund Tarbell, painters who had previously been excluded from the pantheon of great American artists. Yet this revisionist scholarship also led to a virtual erasure of the strong nationalist vein in nineteenth-century American art and criticism. It was not until the pioneering dissertation of Linda Docherty, in 1985, and the more recent scholarship of Kathleen Pyne, Bruce Robertson, and William H. Truettner that art historians began seriously to reassess this nationalist commentary.

Building on the work of those scholars, this study differs both in its frequent use of previously unexamined art commentary and its greater focus on the negotiation of fashion and American identity. Late nineteenth-century American art and criticism pose important questions about the ways in which the art world, as a kind of subculture, reinscribed mainstream tropes for national identity to suit its own needs. The five chronologically organized case studies in this book explore the ways in which art and criticism encapsulated anxieties over American selfhood. All of the painters and critics examined here participated on some level in a campaign for the creation of a national art.

Even though critical texts of the day provide an indispensable richness of detail and a foundation for this book, it differs from much recent scholarship on nineteenth-century American visual culture in its attempt to balance close readings of both written criticism and individual works of art. Obviously, nineteenth-century painting and criticism are not identical. In writing this book I make the assumption that works of art produce their own particular, often richly complex, meanings. Perception of those meanings requires sustained formal and iconographic attention. Paintings such as Winslow Homer’s The Veteran in a New Field (1865), Thomas Anshutz’s The Ironworkers’ Noontime (1880), and Thomas Eakins’s Swimming (ca. 1883–85) never simply mirror culture. Each embodies tensions often obscured in other kinds of discourse; each exposes conflicts and contradictions that underlie the construction of American selfhood.

Rather than attempt to produce a complete survey of late nineteenth-century American art, I analyze a group of paintings by Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz that were produced mainly between the end of the Civil War and 1900. In my view, pictures such as Homer’s representations of hunting in the Adirondacks illuminate the construction of American identity during this period. I readily acknowledge that the book leaves almost untouched such important related topics as portrayals of the American West, vernacular sources in architecture, Civil War monuments, popular lithographs, and Colonial Revival imagery. It is tempting to overemphasize the force of nationalist sentiment in the formation of the paintings discussed in this study, but I have tried not to overdetermine or unrealistically reduce the art. In fact, a complex amalgam of social and artistic forces shaped the ways in which these paintings were produced and received.

Chapter 1 illustrates this point. It explores a set of circumstances following the Civil War that catalyzed the art world’s nationalist impulses. This chapter also examines the largely neglected attempts by critics to contain a European cultural "invasion" through vehement attacks on fashions emanating from Paris, Munich, and London. During this period, a desire for American autonomy collided with aspirations for European sophistication. The Hudson River School—the nation’s long-established, premiere school of painting—suffered a steep decline in reputation starting in the late 1860s. Many critics felt that American art no longer had a center, that dramatic change was needed to revive its credibility. The effects of this criticism reverberated through the American art world during the remainder of the nineteenth century. The huge influx of contemporary European art into the United States from the 1870s until the turn of the century aggravated this peril in the eyes of concerned Americans. Set against the newest European paintings, American pictures often seemed terribly provincial; many American patrons thus preferred depictions of French livestock, European peasants, or views of Cairo. Partly owing to this predilection, the American art world faced the challenge of replacing the Hudson River School’s depictions of wilderness with a new set of national themes that would be both suitably fashionable and transcendently American during a period of great artistic and social change. A pervasive bias among American art collectors against native themes angered most American art critics, who expressed their outrage in various journals and newspapers. Since most critics considered native subject matter a sine qua non for an artwork’s "Americanness," an artist’s choice to render native subjects—New England farm women, rowers on the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, or a New Jersey meadow—was, in itself, thought significant, implying a resistance to the preference for both foreign scenes and the work of European artists.

If Chapter 1 addresses the challenge of inventing a new national art in the face of sea changes in art and culture, Chapter 2 examines how even the most durable national icon can lose its coherence in the face of massive social change. The focus of this chapter is The Veteran in a New Field (1865), Winslow Homer’s painting of a Union soldier who has returned home after the Civil War. This austere, matter-of-fact scene compresses complex, contradictory meanings. Embodying the population’s desire for a return to normalcy, the veteran in the scene employs an anachronistic, single-bladed scythe that evokes an earlier Arcadian America. Yet the scythe also evokes the savagery of battle. Like the rest of the pictures in this study, The Veteran in a New Field elucidates the ways in which artists grappled with constructing a cohesive national identity at a time of disquieting cultural dislocation.

Chapter 3 turns to a group of paintings by Thomas Anshutz, from 1879 to 1880, which were partly a response to critics’ pleas to cast off older national themes associated with the Hudson River School. Anshutz’s scenes exemplify an important, post–Civil War thematic shift in American painting toward contemporary American life. Like the paintings of Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, John G. Brown, and others, Anshutz’s pictures epitomize how this period ushered in a much broader range of contemporary American themes in art, as artists (along with the population of the country as a whole) attempted to come to terms with what constituted "America" in the aftermath of the war. These pictures mark a brief period of ideological openness in American art, when it was possible for painters to render disturbing, socially critical subjects, such as factory scenes and people on the margins of society. That this burst of innovation had dwindled by the mid-1880s raises questions about the negative effects of artistic eclecticism in the last two decades of the century.

Chapter 4 explores how artists often shrewdly exploited the American preference for Old World culture by portraying native subjects that evoked European painting. Focusing on Thomas Eakins’s Swimming (ca. 1883–85), a picture of men bathing at a rural waterhole, this chapter examines how the scene embodies this strategy of mediation. Like many of his contemporaries, Eakins was caught between a desire to retain a distinctively national art and a need to keep abreast of the newest European models. This tension led to the paradox of works that want to appear simultaneously American and foreign. Swimming openly acknowledges its debt to and its entanglement with European tradition: Eakins’s nude figures with their toned physiques clearly emulate antique Greek relief sculpture, and the hazy landscape in which they are set shows a debt to the Barbizon School of painting. Thus Swimming is self-consciously ambiguous in being an American scene that strongly invokes European art and culture. That said, Eakins’s picture affirms that American subject matter was as rich in possibility as any from abroad and that it could legitimately participate in even the most revered traditions of Western art. Swimming also offers an acidic commentary on the puritanical nature of a society that proscribed the artistic depiction of the male nude.

Chapter 5 addresses Winslow Homer’s similar, though less equivocal, attempts to fuse the traditions of American and European art. As Bruce Robertson and Sarah Burns have demonstrated, critics portrayed Homer’s art as quintessentially American. His scenes were hailed as factual and virile; his work was purportedly altogether free from the "taint" of foreign art. Homer’s paintings offered the reassurance of an "authentic" American identity. The unimpeachably national character of his work played an indispensable role in the success of nationalist criticism, which itself made Homer’s own rise in popularity possible. Indeed, critics, along with influential patrons, transformed Homer into a kind of rebel, an artist who brazenly and courageously celebrated Americanness in the face of European imports. This chapter examines a group of Homer’s paintings (including his scenes of Atlantic fishermen, wrecks, and crashing waves) that show how he deftly negotiated the challenge of national identity by picturing distinctively American equivalents to European pictorial traditions. Homer’s Atlantic pictures elevated his reputation because they seemed at once truly American and "universal." Like the nostalgic Colonial Revival landscapes of Theodore Robinson, Childe Hassam, and Willard Metcalf, which are dotted with eighteenth-century churches and houses, Homer’s portrayals of Atlantic fishermen and sailors transformed icons of Yankee identity into emblems of Americanness.

This desire to locate the innately "American" also underlies Homer’s Adirondack hunting pictures, the subject of Chapter 6. These scenes, which are mainly from the 1890s, are Homer’s attempt to revivify an anachronistic ideal of American identity. The Adirondack scenes evoke the myth of an eastern frontier long since domesticated by tourism and denuded by the mining and lumber industries. Nonetheless, the hunters and guides in the Adirondack paintings inhabit a bountiful, seemingly pristine wilderness. These scenes of the north woods promote the idea of a classless frontier yet simultaneously reinforce clear lines of class difference by representing the hunters as "primitive" others. Although these robust men personify the American virtues of virility and self-reliance, they play no role in "civilizing" the wilderness and in fact engage in a practice of hunting known as "hounding" (i.e., driving deer into lakes to drown them) that marked them as poor and "primitive"—which explains why certain critics viewed Homer’s figures as unsavory outcasts. Thus, by presenting the local hunters from the perspective of the elite urban audience he served, Homer infused the myth of the frontier with ambiguity and ambivalence. The Adirondack pictures present a clash between myth and reality and indicate that even the most resilient national tropes are continually reshaped by contemporary perceptions.

Homer’s reputation helped spur a major iconographic shift in American art, which is the focus of the study’s postscript, Chapter 7. What Homer—along with Eakins and Anshutz—bequeathed to the next generation was a renewed passion for naturalism and American subject matter. This change represents a watershed in the nation’s art, a shift as significant as the later, widespread move by American artists to abstraction in the late 1940s. I suggest that this early twentieth-century return to native themes was prompted by—among other causes—the surge of nationalist pride following the Spanish American War. After that war there was a sense in the country as a whole that America had finally achieved autonomy (as a military and industrial power) from European domination.

The nativist Theodore Roosevelt noted, "The United States can accomplish little for mankind, save in so far as within its borders it develops an intense spirit of Americanism. A flabby cosmopolitanism [from European emulation] . . . represents national emasculation." Although it would be misleading to suggest that many American artists and critics were as stridently xenophobic as Roosevelt, their quest for cultural self-determination was driven by similar concerns that the nation’s culture would be robbed of what should be intrinsically its own. The art and criticism examined in this study illuminate the American art community’s insecurity about its own nation’s cultural worth, a self-doubt pervasive among other sections of American society as well. Owing to the perceived superiority of European art, American painters almost always felt compelled to tie their work to Old World prototypes. Yet this abundant need for cultural legitimization was often matched by a desire for artistic autonomy. Thus the art world was a prime site in the nationwide struggle for American identity. A conclusion that seems inescapable is that the dual pressures of the desire for national autonomy and the need for European sanction engendered rich, unresolved contradictions in American art and criticism.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.