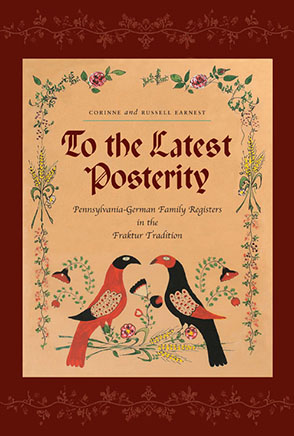

To the Latest Posterity

Pennsylvania-German Family Registers in the Fraktur Tradition

Corinne Earnest, and Russell Earnest

To the Latest Posterity

Pennsylvania-German Family Registers in the Fraktur Tradition

Corinne Earnest, and Russell Earnest

“Beautifully illustrated.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Renowned authorities on fraktur, Russell and Corinne Earnest trace the evolution of decorative family registers from their roots in medieval European illuminated manuscripts to their distinctly American forms that spread through Pennsylvania German culture. The form had a special association with persecuted Mennonites, who used the decorative documents to claim roots in their new home. The documents came to represent the separation from the Old World and the creation of family roots in the New. To the Latest Posterity is filled with examples of family registers from museums and private collections, including early handmade work as well as printed registers that were hand-filled in the nineteenth century. Bringing the art to the twentieth century, the Earnests discuss the adoption of the art by Amish, who continue the practice of illuminated family record-keeping today.

Pennsylvania German History and Culture Series

“Beautifully illustrated.”

“Corinne and Russell Earnest, experts on fraktur, have produced a lovely book filled with color and black and white examples of family registers, both hand-drawn and printed.”

“The numerous illustrations with substantive captions, a grouping of which appears in color, add significantly to creating an understanding and appreciation for the registers. An appendix of artists and scriveners who worked in the family register format, a short chronology of dates associated with the development of registers, and a glossary of terms both used in describing and found upon the registers are all welcome resources included in the book.”

“To the Latest Posterity possesses broad appeal because it combines the interests of the art enthusiast, the calligrapher, the genealogist, and the historian.”

“This comprehensive study explores the world of printed family registers beginning with roots in Europe where information was almost solely limited to baptismal and other records of state church, and extending through several centuries in Pennsylvania to the present day Amish community in which family registers continue to be designed. . . . The volume contains an exceptional array of thirty-seven color plates, illustrating the six forms of Pennsylvania-German family registers. Also included are twenty-nine black and white illustrations. . . . This publication is an important and well-researched addition to Pennsylvania German studies. . . . The publication of this instructive and colorful volume, the first comprehensive documentation of this previously unappreciated Pennsylvania-German family register tradition, splendidly culminates their years of dedicated research.”

“This volume is well illustrated with sixty-seven black-and-white or color examples. Each illustration is well captioned and sourced and includes an additional paragraph of explanatory information. . . . This book can be enjoyed by anyone interested in Pennsylvania German culture, folk art, or family history.”

“To the Latest Posterity offers an impressive and well-documented display of a long-standing but rarely considered vernacular expressive form; as such, it will both prompt and aid future investigations.”

Corinne and Russell Earnest have studied fraktur for over thirty years, and have recorded the genealogy infill from more than 25,000 fraktur. They have published nineteen books about genealogy and fraktur, including German-American Family Records in the Fraktur Tradition, Three Volumes (1991–1993), The Genealogist's Guide to Fraktur: For Genealogists Researching German-American Families, with Beverly Repass Hoch (1991), and Fraktur: Folk Art and Family (1999).

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Prologue

1. Perspectives on Family Registers

2. Pennsylvania-German Family Registers and the Fraktur Tradition

3. Comparisons of Pennsylvania-German and New England Family Registers

4. Texts on Pennsylvania-German Family Registers

5. Forms of Pennsylvania-German Family Registers

Preprinted Broadside-type Family Registers with Printed Infill

Freehand Broadside-type Family Registers

Preprinted Broadside-type Family Registers with Added, Handwritten Infill

Preprinted Family Registers Bound into Bibles

Freehand Family Registers Written on Blank Pages of Bibles

Freehand Family Registers in Booklet Form

Epilogue

Appendixes

Notes

Selected References

Index

Chapter 1

Perspectives on Family Registers

The family register is almost as old as writing itself. By definition, a register is a system for recording details. The earliest "written" family registers were chiseled in stone or painted on plaster (as in Egyptian hieroglyphs) or inscribed on unbaked mud (as in Old Persian cuneiform script). They documented rulers’ lineages and achievements—achievements that often meant subjugating or destroying other peoples. Those from Egypt’s New Kingdom portrayed the principal sons and sometimes the daughters of various pharaohs. These registers meant to ensure that each child, at his or her death, would find favor with the gods. Other family registers include the "begats" from the Old and New Testaments, and, eventually, European heraldry. Other examples abound.

Unlike registers from other parts of the world, most eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American registers do not reach far back into the history of the family. Instead, American family registers present the immediate family; that is, they offer detailed information about parents and their children. Pennsylvania-German family registers sometimes include information about the parents’ parents, but these registers rarely provide details that trace back many generations. Thus, American registers are similar to what family historians today call "family group sheets." Early American family registers on paper, however, frequently featured watercolor decoration in the borders surrounding the text. These hand- or print-decorated registers predate and look quite different from the undecorated and strictly functional family group sheets used by genealogists today.

European family registers, beginning in the Middle Ages, documented titled ancestry or the ancestry of socially conscious persons. But few Americans of German-speaking heritage created family registers to prove aristocratic lineage. Instead, today’s family historians with German or Swiss ancestry create lists of direct ancestors called Ahnentafeln (Ahnentafel in the singular). Ahnentafeln, like European registers, look back in time to discover lines of ancestry. The American Ahnentafel, however, results from curiosity about ancestry—not the desire to document the family’s high station. And again, Ahnentafeln, like family group sheets, solely function as research tools and lack decoration.

Americans should not assume that Pennsylvania-German family registers grew from a similar tradition in German-speaking areas of Europe. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century German-language registers are known in Europe. Some are even hand-drawn, broadside-type family registers in black letter or fraktur lettering and watercolor; some limit their texts to the parents with lists of children. But such documents in Europe are relatively rare. They probably seemed superfluous, for they duplicated what existed in church records. Moreover, they served no official function, and having such a document made for the home may have been regarded as unnecessary and even pretentious if the family was not aristocratic.

In Europe, family registers of another sort were favored by aristocratic—or at least well-connected—families. These registers have more to do with armorial bearings and heraldry than with the detailed history of a family. In present-day Germany, hundreds of volumes provide family information and coats of arms for titled families. According to Klaus Stopp, the Gothaisches genealogisches Wörterbuch der adlichen Häuser is the genealogical bible for noble families, and J. Siebmacher’s Grosses und Allgemeines Wappenbuch is the bible for coats of arms. The Wappenbuch alone numbers more than one hundred volumes. In addition, there are many regional histories, such as Hessisches Geschlechterbuch and the Deutsches Familienarchiv: Ein Genealogisches Sammelwerk, for untitled families. To put this in perspective, just one volume of Ottfried Neubecker’s Grosses Wappen-Bilder-Lexikon has, for the name Ernst (Earnest), eleven coats of arms. That is from just one of hundreds of books on coats of arms. Incidentally, not one of the eleven Ernst coats of arms pictured in the single volume by Neubecker resembles another. In fact, some bear resemblance to coats of arms for people with entirely different surnames. Such "registers" showing coats of arms tell little about specific histories of a family.

The purpose and appearance of the American family register were different from these European examples. Whereas a European register affirmed social status by illustrating ancestry with coats of arms, the American family register documented biographical details about the immediate family. Thus, the American family register focused on the central text, which was occasionally flanked with brief religious or philosophical verses and with decoration that had nothing to do with coats of arms. At least among Pennsylvania Germans, the intent of the family register was not to show status, for most Pennsylvania Germans were rather modest. They sensed that someday, however, their descendants might want to learn about the family in the New World.

When contrasting European and American registers, it becomes apparent that registers made for ordinary families blossomed and flourished in America. Perhaps because they were made for common families, American registers assumed a more humble appearance. They generally lacked the elaborate details that symbolized illustrious heritage—details such as coats of arms or symbols borrowed from them, such as fleurs-de-lis, rams, dragons, chevrons, rampant lions, crosses, eagles, trade symbols, astrological and zodiacal signs, armor and weaponry, and crowns. Some of these motifs transferred to America on fraktur, which, for the purpose of this study, are defined as eighteenth- through twentieth-century decorated manuscripts and certain printed forms made by and for families of Pennsylvania-German heritage. (As Chapter 3 will note, strongly symbolic motifs were used less frequently on Pennsylvania-German decorated manuscripts. Moreover, after transferring to America, such drawings generally became simpler than their more sophisticated and elaborately detailed European counterparts.)

Among Pennsylvania Germans, local schoolmasters and itinerant scriveners created most manuscript family registers. Although they intended the text to become the focus of the register, the addition of art often drew attention from the text. This became especially true in the case of German-language registers as later generations could no longer read them. While Americans continued to appreciate the art, they often had no idea what was written on registers. As a result, the visual impact eventually came to dominate discussion of these manuscripts. But the use of German fraktur lettering and script, or even English-language decorative lettering, plus added illumination, places Pennsylvania-German registers within the larger field of fraktur.

Some believe that family registers, birth and baptism certificates, and other types of fraktur served an official function. In America, among Pennsylvania Germans, this was assuredly not the case. It is unlikely that official documents would have been hand-decorated. In addition, family registers intended for official use would not have been recorded in the family Bible. Most important, they would have been written in English rather than German, for English was and always has been the official language in English North America. Instead, the family register was meant to be enjoyed by the family in the home and to be passed on to succeeding generations. The only official function these documents may have served—and originally, this was not by design—was to document the birth of a soldier or sailor to qualify him, or often his destitute widow, for a pension. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., hold numerous fraktur-related family registers and birth and baptism certificates submitted as proof of a veteran’s age, date of marriage, spouse’s name, and place of birth. Other official uses are known, but generally, these uses were the exception rather than the rule.

Most fraktur were personal documents, whether they were recording personal and/or family data or given by schoolmasters as instructional keepsakes for diligent students. Most were made for rural families of southeastern Pennsylvania, but fraktur were also made anywhere Pennsylvania Germans settled, including Ohio, Virginia (especially the Shenandoah Valley), West Virginia, western Maryland, New Jersey, the Carolinas, and Ontario, Canada. Pennsylvania-German family registers are potentially found, then, in all regions populated by German-speaking immigrants and their descendants. Because many family registers date from the nineteenth century, examples were made for descendants of Pennsylvania Germans and for later German American immigrants and their families throughout the Midwest. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century examples are known from Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and other mid-American states. But by far, most fraktur, including fraktur-related family registers, derive from southeastern Pennsylvania.

Fewer examples of family registers made for people of German extraction are known in the southern states along the Atlantic seaboard. At an early date, Germans began settlements in Georgia, the Carolinas, and throughout the Shenandoah Valley region of Virginia. Except for nineteenth-century family registers printed by the Henkel Press in New Market, Virginia, and booklet family records made by the Virginia Record Book Artist and copy artists (see Chapter 5), few Pennsylvania-German family registers made on paper in southern states are documented. Germans in southern regions had a fraktur tradition, but anglicization occurred early in the South. Thus, finding English-language textile registers in southern states is perhaps more likely than finding examples on paper.

The present volume—in keeping with the fraktur tradition—addresses only works on paper. Many American family registers, especially from New England, are textiles, including ink on silk. We do not cover textiles, such as ink on silk or needlework samplers. Nor do we include tinsel picture–type family registers. (Tinsel pictures are painted on glass, and their texts are written on the reverse of the glass, which is backed with tinfoil and framed. This type of family register dates from the mid-nineteenth century and is still made today, especially among Amish families of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. ) In The Jewish Heritage in American Folk Art, Norman L. Kleeblatt and Gerard C. Wertkin pictured nineteenth- and twentieth-century English- and Hebrew-language registers that grew from a Central European tradition of decorating manuscripts. Although registers were made in America for Jewish families, they did not come directly from the Pennsylvania-German fraktur tradition. Thus, these examples are not included here.

We also exclude from this study fan charts, pedigree charts, family group sheets, printed genealogy books, and other documents now used by all Americans, whether from Europe, Africa, or Asia. Such records warrant their own thorough study, but including these twentieth-century records here would cause this investigation to balloon and lose focus.

Occasionally, family registers appear in Pennsylvania and Virginia church books. One such record is illustrated in Bucks County Fraktur. These records are interesting and worthy of mention, but we exclude them from this study because church records are generally recorded for multiple families in chronological order by dates and within categories of baptism, marriage, and death, so that information concerning a single family is scattered throughout the record. Normally, a single-family entry on a church record page was written when the family wanted personal data updated in the church book. Such records are uncommon. On rare occasions, too, Pennsylvania-German family registers were stitched with colored thread onto punched paper. Some of these were single sheets of punched paper. Others were cut into pages and stitched along the left margin to form a book. Too few examples of either type are currently known, and they are therefore excluded from this volume.

As noted above, we restricted our study to Pennsylvania-German family registers written or printed on paper in the fraktur tradition. Our work shows that, in general, Pennsylvania-German family registers were influenced by the fraktur tradition even after the Civil War, when English gradually supplanted German in Bible records. Local schoolmasters and itinerant scriveners created most manuscript family registers, and descendants of Pennsylvania Germans continued to hire professional scriveners to write genealogical data in Bibles in decorative fraktur lettering, Spencerian English penmanship, or some other calligraphic style until well into the twentieth century. Families could have recorded this data themselves, but their love of color, appreciation for the skill of the scrivener, sensitivity to tradition, and recognition of the value of the register to future generations prompted them to dig deep into their wallets to pay professional penmen.

Unexpectedly, as we examined and recorded more than one thousand primary sources from private and public collections, we determined that a chronological approach to the history of Pennsylvania-German family registers was impractical. The data we compiled pointed instead to another organization—an organization of family registers into six categories, outlined below and discussed in detail in Chapter 5. Although the function of registers in all six groups remained consistent—that is, to create permanent records documenting family data—they varied stylistically and in their historical development.

The six forms of Pennsylvania-German family registers include (1) printed registers with family data, or infill, printed on a printing press; (2) freehand examples; (3) preprinted forms with added, handwritten infill; (4) preprinted forms bound into family Bibles, usually between the Old and New Testaments; (5) freehand registers written on the flyleaves or blank pages of Bibles and other books; and (6) handwritten (as opposed to printed) book-form registers. The first three types are in a broadside format. That is, they were drawn or printed by machine on one side of a single sheet of paper. Often this paper was large, and the record was decorated as if to be displayed. These registers were stand-alone sheets of paper, not bound into Bibles or other books.

The first form—family registers having infill printed on a printing press—presents the most surprises. Not only are these registers rare (for they must have been expensive to produce), but some are also quite early, dating from before 1800. In fact, the earliest known surviving American broadside family register with printed infill is a Pennsylvania-German example printed at the Ephrata Cloister in 1763 for the Bollinger family of northern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (fig. 1). This predates the earliest known New England example, probably printed after 1775 for the Peirce family of Worcester, Massachusetts. The existence of the 1763 Bollinger register is especially surprising, considering that printers from Boston and Philadelphia dominated the colonial American printing market. When searching for the earliest printed family register, one naturally turns to examples from Massachusetts or the Philadelphia area—especially English-language examples. But, to our knowledge, Ephrata produced the earliest surviving printed family register in America, and it was printed in German.

<comp: insert fig. 1 approximately here>

In 1963, Meredith B. Colket wrote that family records were generally not published until the nineteenth century, but he did point out that in addition to the Bollinger example, bibliographers were aware of the 1731 genealogy published by B. Green in "Boston in New England" for the Clap family. The Clap history, however, is a forty-eight-page book and not a stand-alone, broadside-type family register. The full title of the Clap family history reads, Memoirs of Capt. Roger Clap, Relating some of God’s Remarkable Providences to Him, in bringing him into New-England: and some of the Straits and Afflictions, the Good People met with here in their Beginnings. And Instructing, Counselling, Directing and Commanding his Children, and Childrens Children, and Houshold, to serve the Lord in their Generations to the latest Posterity. Judging from this lengthy title, Captain Clap was aware that he was documenting his earliest beginnings in the New World. Moreover, he looked forward—to his "latest posterity."

In actuality, the last ten pages of Clap’s history were written by James Blake Jr. between 1720 and 1731. Called A Short Account of the Author and his Family, Blake’s contribution contains Roger Clap’s family history. The history written by Clap many years before (Clap died in 1691) is more of an account of the early settlement of Massachusetts with autobiographical elements. The distinction between Blake’s contribution and the original Clap narrative becomes important in understanding early family histories and registers in America, for it is actually Blake’s addition that turns Clap’s account into a genealogy.

According to Colket, "the significance of the Memoirs of Capt. Roger Clap as a ‘first’ has not hitherto been adequately recognized." Colket’s point is well taken. He goes on to recognize the 1763 Bollinger family register as an equally important "first" and notes that the Clap family history and the Bollinger broadside "deserve a place as landmarks in the development of printed family records of colonial America." This observation cannot be emphasized enough. The significance of these two early examples of printed family history suggests that immigrant families, along with the next few generations of their descendants, were interested in documenting family history. And what they wrote is especially revealing. As will be discussed below, most family registers in this country, whether in English or German, fail to record where in Europe the family originated. Today’s family historians find this short-sighted omission especially unfortunate, and it is. But it is also telling. The saying "Don’t look back unless you’re going back" seems to apply here: these people were not going back. They were interested in the future.

Colket further wrote, "Germanic peoples frequently employed calligraphers to prepare illuminated family records of birth in Frakturschrift [fraktur writing], for framing and hanging on the wall. In the same manner English people encouraged daughters to embroider samplers showing family data." Colket was referring to Americans of German and English heritage. It is noteworthy that Colket failed to mention that the "English" made hand-drawn registers on paper. He also speculated that the Bollinger register was printed because of the "availability of the famous Ephrata printing press and the current lack of good calligraphers in the area." The latter observation bears addressing, because the Ephrata Cloister was the source of some of the earliest and finest, most classic, hand-drawn fraktur made in America. Its reputation for illuminated manuscripts was well known even in colonial America. In 1772, Benjamin Franklin so admired the art that he showed samples to his friends in London. Thus, in 1763, there was no lack of "good calligraphers" at the Cloister. Colket’s article bears witness to why a study of Pennsylvania-German family registers on paper is needed.

Americans of German heritage can lay claim to an early and widespread interest in recording family events. Gloria Seaman Allen wrote in Family Record: Genealogical Watercolors and Needlework that the "earliest family records in the New World were executed in German fraktur-handschriften, a type of calligraphy originating in the Middle Ages." Despite the Clap/Blake genealogy, Allen may have been right, especially when one takes into consideration the entire body of family-related manuscripts produced by German-speaking immigrants and their descendants. These records were not occasional. Collectively known as fraktur, they became popular in various forms among most denominational segments of German-heritage populations in America. The use of German fraktur lettering and script (or even English-language decorative lettering), with added illumination, places Pennsylvania-German registers within the larger field of fraktur.

Although none treated the subject thoroughly, numerous authors in published studies have recognized family registers as a type of fraktur. In 1897, Henry C. Mercer wrote that among types of fraktur, Bible entries lasted much longer than "other phases of the art" and still continued in his day. In 1937, Henry S. Borneman listed "Genealogical Records" as a type of fraktur. He specifically mentioned those found in large family Bibles, for, in his words, "genealogy occupied a prominent place" in Pennsylvania-German fraktur.

In the most comprehensive study of fraktur, Donald A. Shelley in 1961 not only categorized family registers as a type of fraktur but also—perhaps for the first time—drew attention to preprinted examples. He observed that preprinted registers with added, handwritten infill were not readily embraced by Pennsylvania Germans, as he saw few examples of it. At the time Shelley conducted his research, however, many such preprinted registers remained with the original families. The printed certificates were late (circa 1840 to the present) and often printed in English. Thus, families could read them and determine their relevance. When families recognize their grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ names on a document, they tend to keep that document. Many registers thus remained in private homes and were not available to Shelley. Additionally, when he was collecting evidence, printed family registers had little monetary worth. When they did escape the family’s care, they were not always rescued by the marketplace, and many were discarded. (Of interest, as a way of recognizing that decorated manuscripts existed among other ethnic groups in various regions of the country, Shelley described New England and New York family registers as a form of fraktur. )

Though the second half of the twentieth century spawned much interest in fraktur, no history specific to fraktur-related Pennsylvania-German family registers has previously been published. In Papers for Birth Dayes: Guide to the Fraktur Artists and Scriveners, we documented the known works of major artists and scriveners who worked in the fraktur tradition. Many made family registers (see Appendix A). And in his monumental study, The Printed Birth and Baptismal Certificates of the German Americans, Klaus Stopp documented printers who were candidates for having produced anonymously printed broadside-type family registers for the Pennsylvania-German market.

In general, though, scholars may have assumed that family registers made in the fraktur tradition needed little attention. We listed numerous examples of family registers in the 1997 edition of Papers for Birth Dayes, and there appeared to be little else to say. Admittedly, we were among those scholars who assumed that a study of family registers would be simple and straightforward, advancing knowledge about fraktur only a small step. But, on further analysis, the data we compiled from original manuscripts and printed registers clearly indicated that the Pennsylvania-German family register deserved its own study. An interpretive framework based on an alternative approach to their history—not a chronological sequence—materialized. We discovered that six forms of registers developed almost simultaneously; in many cases, they overlapped. But, to a great extent, they developed independently from one another. We will demonstrate that the various types of registers did not influence each other so much as they responded to individual preferences based on visual appeal or what was practical in terms of gaining access to printers, artists, and scriveners or in terms of preserving data. Hence, the history of family registers of the Pennsylvania Germans represents a departure from other types of fraktur. The more familiar fraktur birth and baptism certificate produced a linear history, such as a chronology showing major developments. The family register, however, took on a life of its own.

By their nature, family registers had to manage sometimes considerable information concerning births, baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and deaths for numerous individuals. Instead of recording a single event, family registers documented several life events. Consequently, unlike most types of fraktur, many family registers were "completed" over a span of several years. In fact, the family opting for a totally printed register soon discovered that it was costly and inconvenient to have data typeset and printed only to have additional information, such as unanticipated births, make the print obsolete. For the same reason, hiring a schoolmaster to decorate and record a register for display was impractical if new arrivals to the family were anticipated. As will be discussed in Chapter 5, problems with updating family information resulted in registers in Bibles becoming the favored solution. Consequently, Bible-entry registers numerically dominated nineteenth- and twentieth-century registers. Nevertheless, various options were available to families wanting registers, and families made choices that suited them. The only commonality among the six categories was the impetus for creating registers in the first place. Family registers arose spontaneously in response to an intuitive sense among Pennsylvania Germans that they needed to document, permanently, their families in the New World.

Surprises awaited us as we researched. Among Pennsylvania Germans, Mennonites and members of other small sects led the way in embracing the family register tradition. More than other religious groups, Anabaptists (including Mennonites) were true refugees, persecuted in German-speaking areas of Europe for their religious beliefs. As such, they responded to American freedoms soon after immigrating by recording family data without fear of authorities tracking down and arresting relatives listed in a register. Yet the Mennonite influence on other religious groups—such as neighboring German Lutherans and Reformed—concerning family registers seems to have been limited. Instead, a spontaneous urge to create registers appeared independently among Pennsylvania Germans of many faiths (not to mention among New Englanders), as will be demonstrated in Chapter 3.

One reason for their wide appeal is that registers stood for no particular faith-based "rite of passage," and thus they were acceptable to people of various religious persuasions. While Pennsylvania-German registers often included references to baptism (a sacrament for Lutheran and Reformed families), the purpose of registers was to record numerous life events and to document family relationships (see Chapter 4). Occasional religious verses appear on family registers, and the theme of death—or the brevity of life—also appears in the art or secondary texts. Generally, though, family registers tended to be secular documents. They were often folded and placed in Bibles or written in Bibles, but this practice was for safekeeping, not for indicating that the register had religious significance. Undoubtedly, some families intentionally stored personal papers in their most cherished book (usually the Bible), but it should be remembered that families also wrote personal records in other books, including cookbooks.

Secondary themes emerged during our research. For example, Americans in general tended to be future-oriented in terms of the registers’ texts. New England and Pennsylvania-German registers functioned in similar ways, but the art on the early registers of these ethnic groups differs (see Chapter 3). And while the urge to proclaim the presence of family in America prompted both English- and German-speaking groups to create registers, the tradition for making family registers—either plain or fancy—remained strong in Pennsylvania-German communities for the better part of three centuries.

Family registers may have remained popular among Pennsylvania Germans for several reasons. In Foreigners in Their Own Land: Pennsylvania Germans in the Early Republic, Steven M. Nolt pointed out that the assimilation of various ethnic groups into the American culture began with Pennsylvania Germans. Assimilation took place quickly for some, but for others, it did not. For example, people whose first language was not English assimilated slowly. While calling descendants of Pennsylvania Germans "the most ‘inside’ of ‘outsiders,’" Nolt recognized that the difference in language set Pennsylvania Germans apart from their English-speaking neighbors. As a result, descendants of Pennsylvania Germans to this day form a somewhat cohesive American subculture, maintaining the "Pennsylvania Dutch" (Pennsylvania German) dialect, religions, folk culture, love of decoration, and rural traditions. Especially in southeastern Pennsylvania, where populations of Pennsylvania-German descendants remain relatively dense, ethnic sensibilities and traditions linger, including the tradition of creating family registers.

One theory has suggested that family registers were a product of changing familial values. Though the eighteenth-century family was community oriented, following the Revolution—when most family registers were made—the family became increasingly self-reliant and self-centered. In urban areas, as husbands found work outside the home, wives and mothers increasingly took over the management of the household. Families had fewer children, and these children enjoyed greater importance. They achieved their own identity and even gained space in the house for privacy in their own rooms. More value was placed on their education, and children were given every possible advantage to succeed. Concurrently, the demand for registers recording the births of children, drawn and decorated by professional artists, increased. It apparently peaked, at least in New England, about 1810.

This theory may hold for New England—but not necessarily for Pennsylvania. Most Pennsylvania Germans were agrarian. During the heyday of their family registers, which lasted well past 1810, they remained rural. Rural families were generally large. As demonstrated by a random sampling of 101 Pennsylvania-German registers, the typical eighteenth- and nineteenth-century families of German heritage averaged 7.4 children. Judging by this sample, augmented with registers made for urban families, city-dwelling families tended to be smaller. While Pennsylvania-German children in rural areas were afforded a nurturing environment, they shared bedrooms, or the loft, within the farm house. And most were not college-bound; they simply wanted their own farms.

The professional portrait painter of New England would have starved if he hawked his talents to the frugal Germans. Rather than being academically trained, the Pennsylvania-German fraktur-producing artist was the local schoolmaster, who would draw a fraktur for a few pence (and, following the Revolution, for fifteen to twenty-five cents). By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, the infiller and decorator of the printed certificate was an itinerant scrivener who went from farm to farm across rural Pennsylvania. He carried his printed family registers and other papers, such as birth and baptism certificates, rolled in a tube slung from a strap. German was his first language and the first language of his clientele. This was true in southeastern Pennsylvania throughout the nineteenth century. Societal changes in New England did not necessarily occur at the same rate in rural Pennsylvania. Thus, regional comparisons have value, but only to a limited degree.

Following the Revolution, pride in our new nation spawned the first major wave of family registers. Later, the centennial of the nation’s independence renewed interest in family history. Late in the nineteenth century, Americans demonstrated significant interest, if not a general fervor, in searching for their roots. About that time, as print and papermaking technologies improved, the price of paper and printing became so reasonable that it was possible to market many types of books, including biographical encyclopedias. Concurrently, family historians began printing and publishing book-length, family-specific genealogies in great numbers. These published histories, more than anything else, may have caused the gradual decline of family registers.

The centennial of independence ushered in another development in family history research. As memories of the Civil War haunted families torn apart by the conflict, many American historical and genealogical societies were founded. The New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston, which was established prior to the Civil War (in 1845), was the first such institution in America. But by far, most societies were formed following the Civil War and the centennial. The Daughters of the American Revolution was established in 1890; the Pennsylvania German Society, a year later. It became fashionable during this time for members of the New England Historic Genealogical Society to trace their heritage to Mayflower immigrants and for members of the Daughters of the American Revolution to trace their ancestry to Revolutionary soldiers. The mission of the Pennsylvania German Society focused not only on German heritage and genealogical research but also on preserving the Pennsylvania-German dialect, architecture, historical records (such as local church records), and folk and material culture.

As activity involving family history research increased, many genealogists in this country developed an interest in tracing families to their European points of origin, but they were often sidetracked by trying to find a famous, important, wealthy, or titled ancestor. The bicentennial witnessed a shift in attitude. Americans in increasingly larger numbers finally decided to look back no matter where the trail led. Curious Americans fully recognized and accepted that their personal history might trace back to the court jester rather than the king, but they were as eager to learn about humble origins as about illustrious ancestors. In short, Americans remembered that we are a nation of foreigners. It was time to take stock of who we were and ponder our beginnings. For many, the search led to primary sources, such as family registers.

The study of Pennsylvania-German family registers is not simple, and for good reason. Original sources are scattered, and most early Pennsylvania-German registers were written in German, even though they were made on North American soil. Thus, Pennsylvania-German family registers are hidden behind an intimidating language barrier. We have presented some tools, including illustrations, names of Pennsylvania-German artists and scriveners who made family registers (Appendix A), a time line (Appendix B), and a glossary (Appendix C), to assist readers in understanding that fragile 150-year-old document they hold in their hands.

Recognizing that thousands of registers made for families of Pennsylvania-German heritage exist today, we have selected illustrations that promote understanding of the history of these registers. The captions include translations of relevant portions that support our findings. Note, too, that while there are numerous variant spellings of names on German-language registers, we have decided to spell names as found on originals.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.