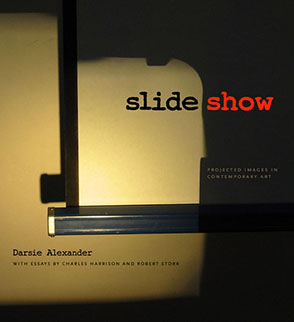

SlideShow

Projected Images in Contemporary Art

Edited by Darsie Alexander, Edited by Charles Harrison, and Edited by Robert Storr

SlideShow

Projected Images in Contemporary Art

Edited by Darsie Alexander, Edited by Charles Harrison, and Edited by Robert Storr

“The fact that release of this book coincides with the coming obsolescence of the medium of slide projection makes it especially timely and valuable.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Interview with Darsie Alexander, Curator, BMA, August 2004

Since the Renaissance, most art has been prized because of the prodigious skills that went into its making. Why would any artist choose to work with slides?

It’s tempting to see slide projection as quick and easy. Indeed, many artists cite these qualities when explaining their initial attraction to the medium. But the process can be complicated, involving not only the creation of the transparency itself but also its arrangement, projected scale, and timing. A single carousel may contain as many as eighty images that must be numbered and ordered, a task that grows all the more complicated with the addition of each new slide grouping. When we rediscovered a piece by one of the performance artists in the exhibition, I thought he was going to cry. The prospect of putting the whole complex thing back together was painful, even though he was delighted to see his work again. Of course, slide projection is low-tech and notoriously accident-prone. But I think the medium owes a lot of its immediacy to its tendency as an apparatus to jam, to burn out a bulb, to turn a well-planned show into a logistical nightmare. Good art often courts disaster.

Is the development of slide art connected to the ferment of the 60s?

During the 1960s and 1970s, public projection of slides became a vehicle for social and political activism. Slide projection’s portability made this possible, enabling artists (Krzysztof Wodiczko, for example) to project powerful, challenging images onto public buildings. When Lucy Lippard wanted to publicize the exclusion of women from the Whitney Annual of 1970, she projected slides against the surface of the museum to protest its curatorial policies. This application of slides as critical commentary had historical precedents: in the 1880s, the photographer Jacob Riis used slides of the urban poor to arouse the concern of people who might have been able to help.

Did the strong associations of slides with family entertainment have any impact on the ways artists adapted the medium?

The fact that the medium promotes a collective viewing experience is important for both artists and popular users. The act of looking at images, especially still photographs, generally involves a single spectator and a stationary object, but with slides you are often sitting in the same room with other people, sharing the experience with them. People who watch Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, for example, find themselves on the same emotional roller coaster. It’s like the family slide show in a way; people participate in a joint emotional response to images of past events. Of course, the memories and feelings such a work stimulates are different for everyone, and that is the reason The Ballad is such a great piece. Marcel Proust as well as Ingmar Bergman have called attention to the mesmerizing power of the magic lantern shows they saw as children.

Is there any connection between those shows and slide shows by such artists as Dennis Oppenheim or James Coleman?

Projection is a mysterious process that evokes all kinds of fantasies. The ancient meaning of the term “to project” is related to the alchemical process for changing base metal into gold. Nearly every artist I interviewed remembers being fascinated by shadows on the wall as a kid, or lying in the dark using the beam of a flashlight to make patterns in the darkness. An artist like James Coleman extends this magical experience to viewers by manipulating the transformative properties of slides as images that are not quite real; indeed, the projections themselves are totally intangible. But all the works in the exhibition invite viewers to read meaning into translucent pictures.

Is slide technology a thing of the past?

Over the past five years, at least, PowerPoint presentations have supplanted slide shows. PowerPoint facilitates overlays, dissolves, syncopated fades, and collage. As consumers, we have become accustomed to a barrage of images and are easily bored. No matter how fancy your equipment, slide projection will always seem a slower, more regulated process. Slides and slide projectors are generally a monocular form of vision and, though users can combine projectors to multiply the frames they project, it is rare that people—including artists—use more than two. And please remember: anyone who would like to use a projector must go to the secondhand market. The last slide projector was manufactured in September 2004.

How does the book SlideShow relate to the SlideShow exhibition?

I am not trying to replicate the exhibition in a book; that’s impossible! The book cannot but give its reader a visual experience radically different from that afforded viewers of the exhibition. I think of the book SlideShow as a document, an expansion, a reflection, an interrogation of SlideShow the exhibition.

“The fact that release of this book coincides with the coming obsolescence of the medium of slide projection makes it especially timely and valuable.”

“This finely conceived and timely exhibition catalogue offers an intelligent exploration of an important and intriguing, but also largely unexamined, aspect of post-sixties art: the slide display utilized as artwork in its own right rather than as a medium for viewing reproductions.”

“While this reader may be biased towards the catalog’s content, the essays are both readable and scholarly. . . . This book is well illustrated with both color and black-and-white plates and contains the usual, if abbreviated, scholarly apparatus.”

Darsie Alexander is Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at The Baltimore Museum of Art. A specialist in contemporary and vernacular photography, she has written on the development of posed photographs, representations of the body, and the role of documentation photographs in 1970s performance art.

Charles Harrison is Professor of History and Theory of Art at the Open University, London. From 1966 to 1975, he was a contributing editor to a leading contemporary art journal, Studio International, and he has published extensively on Conceptualism. He is a member of the artists' group Art & Language.

Robert Storr is Rosalie Solow Professor of Modern Art at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. He is the curator of Site Santa Fe (2004); his exhibitions also include international retrospectiveson Tony Smith, Chuck Close, Gerhard Richter, and Robert Ryman.

Contents

Foreword

Lenders to the Exhibition

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Essays

1. SlideShow

Darsie Alexander

2. Saving Pictures

Charles Harrison

3. Next Slide, Please . . .

Robert Storr

Catalogue

Contributors

Selected Bibliography

Index

Photo Credits

Introduction

What makes a slide qualify as art?

SlideShow attempts to respond to this basic question by first acknowledging that slide projection has been many other things: a means of family entertainment, a way to teach art history, a vehicle for political agitation. Of course, people have always used slides creatively, and many a talented projectionist achieved the lauded status of savoyard during the eighteenth century for producing elaborate shows and spectacular effects using glass slides. Even a masterfully executed display of vacation snapshots may be artful. But at what point does skill give way to what we self-consciously define as art? When did slide projection move from the living room to the art gallery?

To address these issues is to evaluate the terms used to classify art, which may either incorporate or rule out a “popular” medium like slide projection, with its multilayered ties to commerce. Slides have, for much of their history, occupied a place in the marketing and entertainment industries—highly visible outlets, to be sure, but distinct from the traditional realms of fine art. But when the hierarchies of art came under attack in the 1960s, these high/low divisions dissipated, making room for new formats and ideas previously excluded from artistic practice. Artists found this both a great relief and a challenge. Many welcomed the opportunity to leave painting and sculpture behind, but what options stood in their place? Some artists drew from the familiar stuff of their lives, incorporating found objects, reproductions, and fugitive materials into their artworks. Others turned to readily available technologies for inspiration. Slide projection was one such outlet, a standard tool of the art trade that seemed to offer tremendous creative potential, especially for those looking to animate (and automate) their images. Indeed, in the increasingly hospitable climate for moving images established in the 1960s, slide projection bridged aspects of still photography and film in a distinct and meaningful way.

An extremely heterogeneous medium, slides could be adapted to a wide range of applications at a time when artists sought unusual visual combinations and attributes in their works. A painting requires a degree of finality, but a slide projection can be reinvented each time it is shown, with new and different images switching in and out according to specific needs. Magnification, speed of delivery, and sequence become variables of the medium; artists can manipulate and tweak them at any stage of the process. This flexibility generated widespread experimentation with the process itself, resulting in works that could just as easily reside in a live theater as an art gallery—a blurring of lines that artists welcomed.

The title of this exhibition, SlideShow, recognizes the viewer’s experience of watching slides as well as the artist’s experience of formulating and ordering them. Though a slide itself is often an image, a slide show is a phenomenon, an event that occurs at a specific time and for a designated purpose. Anyone old enough to remember slides may find it difficult to think of the medium without immediately conjuring up specific moments spent observing bright pictures flash on a screen, be it in a classroom or a hotel lobby. These are the sites of slides, the ways in which they are made physical by machine projection. For artists, showing slides involves a process of envisioning how they will look as pictures inside architecture and, in some cases, surrounded by sound. No wonder, then, that the earliest work in slide projection focused on the particulars of mediation. How does an image change depending on where it is sequenced in a larger progression? In what ways do single images contribute to the overall effect of multiple ones? These issues affected both how artists conceived their works and what demands they placed on audience reception. The fact that slide projectors are optical devices that inform (and sometimes complicate) perception provides an underlying theme for many of the works in this exhibition.

SlideShow includes nineteen installations at various levels of scale and complexity. Some, like Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a personal story of sorts, are presented in closed environments. Others, like Jan Dibbets’s six-carousel piece Land/Sea, relate directly to the architecture and thus to the surrounding environment of the spectator. Despite the range of works on view and their relative familiarity (or unfamiliarity) to general audiences, a historical structure linking them to Conceptualism, performance, and narrative art runs throughout. These categories are necessarily loose, as slide projection enables the mixing and matching of many different elements and themes. The more recent works, for example, are noticeably nostalgic in tone: they reflect on the use of slide projection as a vernacular medium as well as one with ties to 1960s–1970s Conceptualism. Exhibition visitors will observe that earlier works are largely single-carousel projections; later pieces are comparatively more complex. As projected imagery in art received more competition from the sped-up world of commerce, opportunities for both critique and a new look emerged, resulting in a growing emphasis on scale, sound, and color saturation in the production of slide works today.

This publication documents works and artists in the exhibition and analyzes the larger themes and histories they represent. In the introductory essay, I outline major developments in the art of slide projection, focusing on its oscillating status as a form of photography, a distinct medium in itself, and—as one artist put it—“a cheap way to make a film.” I also pay special attention to the beginnings of slide projection as a contemporary art practice, looking in particular at the question of why so many artists more or less simultaneously chose slides, expanding their applications of the medium far beyond mere illustration and documentation. Charles Harrison’s essay, “Saving Pictures,” examines the changing parameters of art during the 1960s and 1970s, noting the erosion of hierarchical distinctions within traditionally distinct genres and the gradual loss of the “frame” that renders art autonomous, unique, and authentic. Slide projection, he proposes, represents a “detachment from the cultural status quo with intangibility and physical impermanence of imagery.” Taking a different tack, Robert Storr’s “Next Slide, Please . . .” concentrates on slides as the “common coin” of the art world—artifacts that historians and artists rely on to tell their stories, illustrate their points, and disseminate their material. In some ways, the leap from practical necessity to creative possibility would seem to be an obvious one for artists, but the transition also meant dealing with the very specific nature of the slide-as-medium. These essays are followed by detailed entries on the individual works in the exhibition, written by Rhea Anastas, Thom Collins, David Little, Molly Warnock, and me. Each entry offers an analysis of the piece in question and its role in the artist’s overall body of work. Together, the elements of the book complement one another and even, at times, mark differences of opinion and attitude. By taking a variety of approaches, the texts open up diverse avenues of thought, yielding new insights into their common subject.

Writing on the subject of slide projection in post-1960s art occurs, with odd serendipity, at the moment that slide projectors are being rendered obsolete. Last September, a memo from Kodak went out to all interested parties announcing the official termination of the standard slide projector, an apparatus that has projected and reproduced images for generations of audiences. Now we are in the position of posthumously examining slide projection as art, a task that requires an assessment of particular individuals as well as the historical circumstances that determined, in part, their changing applications of slide technology. We notice, for example, a growing interest in continuity and imagistic flow in later slide works replacing an earlier fixation on the still image as the structural foundation of slide projection. This shift toward steady, seamless images is now apparent elsewhere in our lives, as visual stimuli endlessly stream into our homes and work environments over cable and telephone wires. How do we—as consumers of popular culture—separate and edit this vast array of information? Where does the still image fit within these increasingly complicated networks? The termination of slide projection as such may signal the end of an era; it may also represent the culmination of a wider investigation into the transience of images and the fleeting nature of perceptual experience. Indeed, what accelerates may eventually disappear. Though the history of slide projection may be over, the analysis has just begun.

Darsie Alexander

June 2004

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.