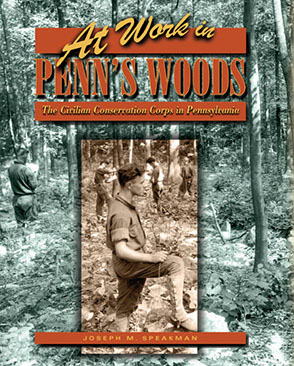

At Work in Penn's Woods

The Civilian Conservation Corps in Pennsylvania

Joseph M. Speakman

“An excellent study of state history with national themes.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

In Pennsylvania, the CCC had one of its largest and most successful programs. The state recruited the second-highest number of workers and had the second-highest number of work camps in the country. Gifford Pinchot, perhaps the most famed conservationist of the first half of the twentieth century, was governor of the state in 1933, and his state foresters were well prepared to make use of the abundant labor the CCC made available to them. The Pennsylvania CCC men planted over 60 million trees in a state that had been scarred by clear-cut logging, rampant forest fires, and destructive tree diseases. They also worked at creating and upgrading state park recreational facilities; some of the camps did historic preservation work at Gettysburg, Hopewell Village, and Fort Necessity. A dozen camps provided assistance to farmers on soil conservation projects.

Aside from conservation work, the CCC program also played another important role in providing relief assistance to Pennsylvania’s families in need. The men were paid $30 a month, but usually $22–25 of that was sent home to their families, who were often on relief and in need of the extra money their sons earned. In their free time the men were given the opportunity to take courses in a variety of academic and vocational subjects to train them for life after the CCC. At Work in Penn’s Woods, the first comprehensive study of Pennsylvania’s CCC program, combines administrative history with portraits of many of the men who worked in the camps. Speakman draws on archival research in primary sources, including some source collections never used before, and on interviews with former CCC men.

“An excellent study of state history with national themes.”

Joseph M. Speakman is Professor of History at Montgomery County Community College near Philadelphia. The inspiration for the book came from conversations Speakman had with his father, who served in Pennsylvania's CCC in 1933–34.

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. The First Year of the CCC in Pennsylvania

2. Enrolling Pennsylvania Men for the CCC

3. The CCC in Penn’s Woods

4. African-Americans in Penn’s Woods

5. Farewell to the Woods

Appendix 1: CCC Camps in Pennsylvania, 1933–1942

Appendix 2: CCC Work Projects in Pennsylvania

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

The Civilian Conservation Corps was one of the earliest and one of the most popular programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. It was created in March 1933 as part of the “Hundred Days” package of programs intended to combat the myriad causes and effects of the Great Depression. Before it was shut down in the summer of 1942, the Corps recruited more than two and one-half million unemployed young men and placed them in army-run residential camps in mostly rural locations to work on natural resources conservation. We might think of it as an early “green” project. A Gallup poll in 1936 found 82 percent of the American people supporting the program, and another poll in 1939 found 11 percent picking it out of the extensive alphabet soup of programs in existence by then as “the greatest accomplishment” of the entire New Deal.

The numerous agencies of the New Deal have often been sorted into the categories of relief, recovery, or reform, but the CCC was one of several programs that actually embraced all three categories. Intended primarily as a work relief project for needy youth, it was also designed to promote economic recovery by sending most of the men’s pay back home to their families, thus increasing the purchasing power of consumers. But, in the minds of Roosevelt and many of the CCC administrators, the program was also going to reform the moral health of the nation’s youth while it promoted more rational conservation policies. As Sherwood Anderson put it after visiting a CCC camp: “They are making a new kind of American man out of the city boy in the woods, and they are planning at least to begin to make a new land with the help of such boys.”

The CCC had a complicated administrative structure—a direct result of the enormous logistical challenges associated with mobilizing large numbers of men from around the country and transporting them to designated work sites. The Departments of Labor, Agriculture, and Interior worked closely with the War Department in recruiting and supervising the men. The army, with its nine domestic Corps, provided the organizational framework for bringing the CCC to the states.

Pennsylvania, part of the army’s Third Corps area, proved to be one of the most successful state programs, uniquely characterized by an abundance of unemployed young men and plenty of conservation work to occupy them. The CCC was meant to alleviate the dual stresses of unemployment—the economic and the psychic—and Pennsylvanians were suffering these stresses to an appalling degree. But the Corps was also designed to relieve some of the stress on the land; here, too, Pennsylvania was in sore need.

The Depression that began in 1929 hit Pennsylvania particularly hard, creating a large number of potential recruits for CCC camps. In this regard Pennsylvania resembled other eastern states. It was also typical of eastern states in that many of its young recruits, particularly in the later years of the program, were sent out to western states where there was always more conservation work to be done than locally available men could handle. But Pennsylvania was also a bit like those western states in that it was able to employ the vast majority of its own men in its own work camps and was also able to absorb hundreds of men from other states, particularly in the early years.

The Keystone State was able to provide such abundant conservation work opportunities in part because irresponsible logging in earlier generations had produced environmental damage that needed restorative attention. But also, thanks mainly to Governor Gifford Pinchot, the state’s Department of Forests and Waters was able to provide an experienced cadre of trained foresters to supervise most of the conservation work done by the CCC in the state. Moreover, Pinchot’s administration had created a new State Emergency Relief Board (SERB), which in 1933 had the trained personnel to identify and recruit needy young men for the camps. The CCC utilized the labor of these young men in a variety of conservation activities in Pennsylvania, including planting trees, controlling erosion, building state park facilities, and restoring historic sites. The beauty and environmental health of large areas of the state still display the beneficial effects of that short-lived program.

But while the CCC provided immeasurable benefits for the unemployed men and the ravaged landscape they worked on, its operation in Pennsylvania also revealed the serious limitations of the entire program. Created as an emergency measure and rushed through Congress in little more than a week, many of its features were not well thought out. Although there is no doubt of the initial general enthusiasm that greeted the CCC, as time went on serious criticisms of the original plan surfaced. In particular, the speedy launching of the program in 1933 required a central role for the army in establishing and supervising the work camps. But the army’s role brought with it a pronounced military flavor that soon created problems of image as well as administrative conflicts with civilian administrators and ended up weakening the popularity and effectiveness of the program. Placing the educational activities of the camps, an add-on feature to the original scheme, under the authority of military officers turned out to be a particularly bad misstep.

A more general failing of the CCC was that it was only a partial solution to the problems of unemployment and conservation. It could not take all the young men who wanted to enroll, and a high percentage of those whom it did enroll it could not keep for the full enlistment period of six months. It undoubtedly provided colorful and even exciting benefits to many young men and their families, and its contributions to conservation were enormous. But its effectiveness would have been even greater if it had adopted a more varied approach to employing young people on conservation projects than the exclusive quasi-military model it followed.

Looked at from a contemporary perspective, the omission of women and the segregation of African-Americans stand out as the most glaring deficiencies of the CCC. Although these discriminations must be seen in the context of the more primitive social mores of the 1930s, they nonetheless weakened the CCC as both a relief measure and as a conservation program. In denying opportunities for women and limiting them for blacks, the CCC passed over many deserving young people and denied the land the benefits of their skills.

Because Pennsylvania had such a large and successful CCC program, it offers an ideal microcosm in which to study the successes and limitations of the CCC idea. It will be useful to begin by establishing the environmental, economic, and political context in which the state’s CCC camps were established.

<1> A Wooded Land

Pennsylvania—“Penn’s Woods”—was given its name by King Charles II of England when he chartered the colony to William Penn in 1681. Penn himself, in modest Quaker fashion, would have preferred “New Wales” or “Sylvania,” but the king insisted and most inhabitants of the state ever since have thought it a felicitous decision. It certainly was a descriptive name, because at the beginning of European colonization probably all but 2 or 3 percent of the state’s 28 million acres were covered with thick forests. Today, about 58 percent of the state is wooded, but in the intervening years wholesale destruction of much of the state’s timber resources occurred, especially due to the irresponsible large-scale logging of the late nineteenth century.

The geography and climate of Pennsylvania produced and, for a while, protected its vast forests. The weather is temperate, with abundant rain and snow, and many of the tree-producing regions are in the relatively isolated middle and western portions of the state where two great mountain ranges run diagonally across the state from southwest to northeast—the Blue Mountain Range of ridge and valley in the center and the Appalachian Plateau in the west and north. These have been the areas of white pine and hemlock (the state tree). There is also a narrow range of beech, birch, and red maple along the sparsely settled northern border. Chestnut trees once comprised about 20 percent of all the state’s trees, some measuring seventeen feet in circumference and providing highly desirable lumber and bark as well as nourishing nuts. But around 1906 a fungus from China hit the state and the resultant “chestnut blight” destroyed virtually all those prized trees by 1940. It still attacks any chestnut sprouts hardy enough to surface.

Another major feature of Pennsylvania’s geography important to its forestry history is its river drainage system. The state has three major rivers with their various tributaries: (1) the Delaware River, fed by the Lehigh and Schuylkill, in the eastern third of the state; (2) the Susquehanna, including the Juniata, in the central portions; (3) the Ohio, created in Pittsburgh by the Allegheny and Monongahela, which drains the western third of the state. These river systems are strongly affected by the forests of the state whose roots and leaf canopies absorb and moderate much of the rain fall, thereby limiting soil erosion and floods. In addition, these rivers historically were linked to the forests as highways of commerce for the logging industry of the nineteenth century: workers floated logs or rafts of logs tied together downstream to the sawmills. The West Branch of the Susquehanna River, carrying logs to Lock Haven and Williamsport, was the most important of these watery boulevards.

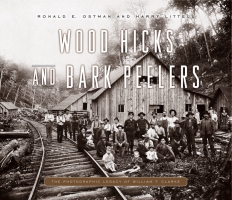

The arrival of large-scale commercial lumbering around 1850 began to mar the look of the state and its ecology like nothing before or since. At that time, the small-enterprise timber industry, widely scattered and serving local markets, was replaced by enterprises operating on a hugely vaster scale and serving distant markets with virtually unlimited demand. This new phase of the industry had begun in Maine and then moved on to New York and Pennsylvania before heading to Michigan and other parts west later in the century. By the time the industry centered on Pennsylvania, its new character had evolved in particularly destructive ways. Lumber companies would purchase thousands of acres, set up logging camps and proceed to clear-cut the forests, usually in winter to facilitate the movement of logs across icy and frozen ground to streams soon to swell with springtime melting. After the logging companies had denuded the land of its trees, they abandoned it to tax delinquency sales, thereby leaving vast acres of unsightly stumps, unprotected soil, and volatile brush materials. Heavy rain would not be as easily absorbed by the root systems of trees or interrupted by their vegetation, and the erosion of topsoils would follow, scarring the land and contaminating downstream drinking water. Sudden torrents of run-off waters would also create flooding in downstream communities.

As a consequence of this destructive logging, the state’s heretofore isolated and untouched white pines, some rising 150 feet high and containing enough lumber to build a good-sized house, were almost completely eliminated. The state’s hemlocks were similarly devastated. Not only was hemlock lumber prized, but the bark was also in great demand by the tanning industry. Loggers would strip the bark, leaving the logs to dry out for months so that they would float better. But what often happened was that these logs would simply provide more fuel for uncontrolled forest fires that would sweep the ravaged areas, fires burning so hot that the soil itself would be damaged. Forests may eventually recover from this kind of damage, but without careful management, it can take up to 120 years for them to return to productive use. The first growths to spring up often are dominated by undesirable vegetation that hampers the return of the more valuable species. In Pennsylvania today there are only a few hundred acres of old growth forest, chiefly in the Alan Seeger Natural Area in Huntingdon County.

Near the beginning of this tragic story, Williamsport, Pennsylvania, on the West Branch of the Susquehanna River in the center of the state, became the lumber capital of the world for a short time. Logs were cut and marked upstream and floated down the Sinnemahoning, the Loyalsock, the Clearfield, and other tributaries to be captured by “booms” down river. The boom at Williamsport served the several dozen large sawmills established there by midcentury. It was an enormous holding pen, eventually six miles around with a capacity of about one million logs. The spread of railroads later made it possible to transport logs without having to float them down rivers. The boom at Williamsport eventually became obsolete, and it was dismantled in 1909.

<insert figure 1—loggers on felled trees—near here>

The demand for lumber continued to increase throughout the late nineteenth century, driving the reckless clearing of Pennsylvania’s forests. Although Michigan’s production surpassed that of Pennsylvania by 1870, the Keystone State continued to produce increasing amounts of board feet, not peaking until 1899. The end of Pennsylvania’s short-lived preeminence in the lumber industry was, in part, due to the simple fact that much of its readily accessible forest resources had been used up. It is estimated that by the turn of the twentieth century, only about nine million acres, or one-third of the state’s acreage, was still forested. Of what was left, fires consumed about 400,000 acres a year, and timber was actually being imported into “Penn’s Woods.” People used language like “desert” or “the Allegheny Briar Patch” in referring to the millions of acres of once prime timber lands then standing in ugly and ecologically dangerous conditions.

Fortunately, some far-sighted conservationists began to raise alarms and promote solutions. Among the earliest was Joseph Trimble Rothrock, “the Father of Pennsylvania Forestry.” Rothrock was born in McVeytown in Mifflin County in 1839 and educated at Freeland Seminary (which later grew into Ursinus College) and the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a medical degree in 1867. He was instrumental in establishing the Pennsylvania Forestry Association in 1886, the first such state organization in the country, and became its first president. When the Pennsylvania Commission of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture was created in 1895, Rothrock became, logically, the first commissioner.

Although not formally trained as a forester, Rothrock was committed to promoting the new ideas of conservation. Over the next ten years he expanded the activities of his commission, especially in the area of fire protection. By the time he retired from his post in 1906 he had created a separate Department of Forestry in the governor’s cabinet, he had helped establish Pennsylvania’s first professional School of Forestry at Mont Alto, and he had professionally trained foresters in his employ. Rothrock was also successful in creating state-owned forest reserves, the first such lands being acquired through tax delinquency sales from logging companies.

<1> A New Breed of Conservationist

After Rothrock, Pennsylvania was served by several capable and increasingly well-trained heads of the Department of Forestry. Of special note was Gifford Pinchot, who served under Governor William Sproul from 1920 to 1922. After Theodore Roosevelt, there was no more important individual in popularizing conservation ideals than Pinchot, and after Franklin Roosevelt, there was no more important individual in the establishment of the CCC in Pennsylvania.

Light years of social class, money, and education would seem to separate a privileged young man living in a Gilded Age mansion in upstate Pennsylvania from the down and out young men in the towns and farms of the same state in the Depression spring of 1933. But the 19,000 men from Pennsylvania who enrolled in the state’s first CCC camps that season, and the 165,000 who followed them over the next nine years, can be said to have been started on their adventures when James W. Pinchot recommended that his oldest son, about to head off to college, pursue a career in forestry.

The baronial estate was Grey Towers, built in the 1880s and still standing, overlooking the upper Delaware River just outside the Pocono Mountain town of Milford. It was James W. Pinchot of the family’s second generation who built Grey Towers as a summer house. In 1885 his oldest son, Gifford, who had been born in Simsbury, Connecticut, on August 11, 1865, was preparing to enter Yale, soon to become a family tradition. Gifford’s mother, Mary, née Eno, could trace her origins back to the founders of Connecticut and was from an even wealthier family than the Pinchots. Prospects were bright and assured for this young scion, but Gifford was still unsure of a specific career goal.

In a conversation pregnant with future significance for American politics and conservation, Father (always “Father” in Gifford’s charming and feisty autobiography, published posthumously in 1947) suggested forestry as a field in which the young man might find a career of useful service. Pinchot later recalled that at the time of this conversation, not only were there no forestry schools in the United States, but the country was also in the midst of “the most appalling wave of forest destruction in human history.” Although there had been some attempts at national and state levels to preserve woodlands, notably in Yellowstone National Park after 1872, conservation in the emerging sense of the rational management and utilization of finite resources was still largely viewed as unnecessary and, indeed, “ridiculous.”

After enrolling at Yale, Pinchot took as many science and botany courses as he could manage. But if he intended to pursue forestry as a career, he would have to continue his studies abroad. In contrast to America, where woodlands had always seemed limitless, in Europe the need to manage the finite resources of forests had long been recognized. Individuals were no longer allowed to cut and clear at will, leaving the topographical and environmental mess for someone else to clean up. Control of fires, erosion, and flooding were all dependent on the practice of scientific forestry, and there were several well-established schools of forestry in Europe.

Pinchot solicited advice from several quarters and decided to attend the French forestry school in Nancy. He attended classes for thirteen months, not completing the program but judging himself ready to manage forests and anxious to establish primacy in his chosen field. Upon his return to the United States, he essentially invented a career for himself and became the first American-born forester.

From the start of his career, Pinchot understood forestry as something altogether different from how it was commonly understood in his day. Several forestry organizations already existed in the United States, including the American Forestry Association in which James Pinchot had been active, but they were primarily devoted to the preservation of wilderness areas. In Pinchot’s mind, however, forestry was not primarily about preserving scenic beauty; it was about the systematic management of woodlands with a view to maximizing their “sustained yield.” It involved, for example, the periodic cutting down of mature trees, rather than letting them rot in untouched splendor. “Forestry is tree farming,” he wrote. “Forestry is handling trees so that one crop follows another. To grow trees as a crop is forestry.” Later on, when the U.S. Forestry Service produced a handbook on woodsmanship for the CCC, it instructed the young men in the same Pinchot-like philosophy: “Conservation means the preservation of natural resources for economic uses. . . . Forestry is the use of the land to grow a continuous crop of trees. Forestry does not mean the preservation of trees as in a park. . . . Forestry is as much a commercial undertaking as is the growth of farm crops.”

Turning down an offer from the U.S. Division of Forestry, Pinchot took the advice of Dr. Dietrich Brandis, a German forester who had become his mentor in Europe, and chose to gain experience in private forestry work before embarking on a career of public service. He did a little consulting work for timber companies and then was hired by George Vanderbilt to manage the forests at his Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. This work earned Pinchot a reputation in his young field, and when Bernhard E. Fernow (another German-born forester) retired as head of the Division of Forestry in 1898, Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson appointed Pinchot as his successor. The position now required a civil service test, which Pinchot was obliged to make up himself! Before he had the opportunity to take it, however, President William McKinley stepped in and waived the requirement.

The next eleven years were busy ones for Pinchot. He oversaw the expansion of the division into a bureau and then into the United States Forestry Service. Meanwhile, he also helped establish the Society of American Foresters in 1900 and set up summer camps in forests to provide work for college students, an interesting foreshadowing of the CCC. He and his family helped establish the Yale School of Forestry in 1900, with summer classes available on their Milford estate. Pinchot continued in his government post under Theodore Roosevelt, and by the end of Roosevelt’s second term in 1909, Pinchot had become the acknowledged leader of the young and growing cadre of American foresters and an articulate ally of the president on conservation matters. One of his successors as forester, William B. Greeley, later remembered the aura Pinchot projected in the field: “Pinchot was very much a man’s man. He could outride and outshoot any ranger on the force. If camp was within a mile of a stream of any size, he invariably had his morning plunge; and if the stream came from a snowbank a few miles up-canyon, all the better.”

After Roosevelt left office, Pinchot kept his position in the new administration of William Howard Taft but was uneasy with some of the new president’s appointments from the corporate world. He soon involved himself in a dispute with one of those appointees, Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger, over the disposition of some Alaskan lands. The ensuing “Ballinger-Pinchot controversy” resulted in the forester’s publicly and rashly criticizing the secretary and, implicitly, the president. Taft, described later by Pinchot as “weak rather than wicked,” fired him for insubordination and thereby raised a storm of criticism that soon spread to other Taft policies and eventually returned Theodore Roosevelt to the national arena as the Progressive, or “Bull Moose,” candidate for president in 1912.

Pinchot, of course, supported Roosevelt in 1912 and in the same year was invited by freshman New York State Senator Franklin D. Roosevelt to give a slide show to the state legislature on the need for forest conservation. This was the beginning of a personal and professional relationship between the two men that continued for the rest of their lives.

The Bull Moosers carried Pennsylvania in 1912, but Pinchot’s own political ambitions in his home state were blocked by the Republican machine in Pennsylvania, headed by Senator Boies Penrose. Nevertheless, in time he managed his way into state government when Governor William S. Sproul appointed him Pennsylvania commissioner of forests in 1920. He proved, unsurprisingly, an active commissioner, reorganizing the department and setting up twenty-four forestry districts with a trained forester supervising each. He also created the best forest fire protection system in the country, acquired some 77,000 acres of additional forest land for the state, and succeeded in getting his appropriations doubled, thereby increasing salaries and morale in his department. His nurseries were able to distribute three million seedlings to the owners of private forests for erosion protection.

Pinchot was also helpful in improving the first state forestry school at Mont Alto, which began offering bachelor of science degrees in forestry, thus expanding the pool of trained foresters in the state. Although state purchases of forest reserves during his tenure were modest in scope, the federal government had created the Allegheny National Forest in the western part of the state in 1921, bringing an additional 400,000 acres of the state’s forests under professional management. One student of this phase of Pinchot’s career sums up his work as commissioner as having provided “strong executive leadership, dynamic public relations, and diversified forest work.”

With the death of Penrose in 1921, the political path was cleared for Pinchot to run for governor. Elected in 1922, he moved quickly to implement bureaucratic reforms designed to promote his conservation ideas. He combined the Department of Forestry with some other agencies to create a Department of Forests and Waters. The new department was headed for a while by one of Pinchot’s protégés, Robert Y. Stuart, who went on to become forester in the United States Forest Service and an important ally of President Franklin Roosevelt in getting the CCC off the ground in 1933.

This increasingly professional attention to managing Penn’s Woods meant that by the time the CCC was created in 1933, Pennsylvania’s forests had recovered significantly from their low point at the turn of the century. Forests now covered about sixteen million acres, including about two million under state supervision. Most of the CCC camps would be established on these state-managed lands.

Nevertheless, not all was well in the state’s forests. Aside from the chestnut tree blight, there were other dangers arising, chiefly gypsy moth destruction of oak trees and the white pine blister rust. But the most serious problem continued to be the annual scourge of forest fires. Fires were caused accidentally by lightning or careless campers, but sometimes they were deliberately set as protests against large corporate absentee land owners. But the railroads were the chief culprits. Sparks emitted by locomotives and fires set by railroad clean-up crews were the causes of most fires. Although Pinchot had begun to build steel watch towers and improve communications, fires still burned several hundreds of thousands of acres a year, mainly in the spring after the snows had melted and before the green foliage had matured. The fall was the second most dangerous season, when the leaf protection of the summer fell as potential kindling onto the forest floor.

There would be plenty of forestry work, then, for the young men of the CCC when they began pouring into Pennsylvania’s work camps in May 1933. The state’s Department of Forests and Waters during Governor Pinchot’s second term in 1933 would be ready to cooperate with the program by providing plenty of work projects and trained forester supervisors. With the possible exception of California, no other state was as well prepared to effectively utilize CCC labor as was Pennsylvania. And the Depression, which had hit the state particularly hard, would ensure that there was plenty of labor available for conservation work.

<1> The Great Depression in Pennsylvania

When President Roosevelt signed the legislation creating the CCC on March 31, 1933, the Depression was three and a half years old and seemingly worsening with every month. Banks had closed, businesses had failed, and breadlines curled around blocks in the major cities. Among the growing numbers of unemployed, perhaps as many as two million, mostly men under thirty-five, were on the road, riding the rails, hitching rides, or just walking from town to town in search of work or simply to give the families they left behind a greater chance of receiving the meager relief help still available. Among these unhappy wanderers were uncounted numbers of teen-aged “tramps” who roamed the country, looking for work or excitement or just escaping domestic squalor. One undercover study of five hundred of these homeless children counted fifty-five of them from Pennsylvania, the highest number from any state in the sample.

<insert figures 2 and 3—Hooverville & Cox delivering relief—near here>

The older unemployed tended to stay put, selling apples on street corners, looking for odd jobs, or setting up “Hooverville” housing out of the detritus of a collapsed industrial society. Many discouraged men and women simply idled away, hoping something would turn up, while increasing stress built up within families. Families were staring at “nameless horrors” creeping toward them from “out of the darkness,” and reactions wavered over a narrow spectrum from fear through numbness to outright rebelliousness in proportions historians still argue about.

The people of Pennsylvania were especially hard hit. The population of the state was more than nine million in 1930, ranking second in the nation behind New York. It was a curious state in that its urban population of six and a half million ranked it second, again behind New York, but its rural population of three million also ranked second (this time behind Texas). The state’s post–Civil War reliance on heavy industry made it particularly vulnerable to the Depression since those industries were harder hit than the service economy. Moreover, most of the people in the rural areas were dependent on the state’s farms, and agriculture was, if anything, in even worse shape, accelerating the downward slide begun in the 1920s.

Agriculture was not the only economic sector in the state that had not fully shared in the uneven boom years of the Roaring Twenties. Some industries vitally important to the state’s economy, such as coal mining and textile manufacturing, had barely held their own in the decade since World War I had ended. Unemployment in Philadelphia, famed for the diversity of its manufacturing sector, was above 10 percent in the year before the Depression started. In the Pittsburgh area employment in steel industries in 1929 was 40 percent below what it had been in 1923. According to the director of industrial relations in Pennsylvania, average wages in Pennsylvania’s manufacturing industries were among the lowest in the Northeast and about 33 percent lower than in New York. Sweatshops still existed in the state, paying women $4 a week, less than the standard relief grant.

In July 1932, the Community Council of Philadelphia described unemployment in the city as so bad that it was creating conditions of “slow starvation and progressive disintegration of family life.” Tuberculosis rates in the state had recently doubled, and more than one-quarter of school children in the state were said to be undernourished. Relief funds, heretofore the responsibility of local county boards but now supplemented by the limited funds the state provided after 1931, were near exhaustion with many families receiving less than $3 a week in assistance.

Governor Pinchot’s analysis of the causes of the Depression stirred him to righteous anger. He blamed the Depression on “the most astounding concentration of wealth in the hands of a few men that the world has ever known.” Citing a Federal Trade Commission study in 1926 showing that 1 percent of Americans owned 60 percent of the nation’s wealth, Pinchot argued that the purchasing power of consumers could not keep up with the rising productivity of the economy. Once the Depression hit and wages fell faster than prices, the problem of underconsumption was compounded and cutbacks and layoffs resulted in further decreases in purchasing power.

By the time Franklin Roosevelt entered the White House in 1933, statistical bottoms were being plumbed in terms of unemployment and business failures. Curiously, in a nation obsessed with size and statistics, there were as yet no reliable United States government figures on unemployment, but estimates by various private organizations (supported by later studies done by the Department of Labor) suggest a national unemployment rate of about 25 percent in March 1933.

The situation was even worse in Pennsylvania. In 1929 Pennsylvania had more than 17,000 individual manufacturing establishments, second only to New York. By 1933 about 5,000 of these were completely gone, and the others operating at low capacity, with devastating effects on employment levels. Governor Pinchot reported in early 1933 that only about 40 percent of the state’s workforce was fully employed, with about 30 percent employed half-time or less, and another 30 percent, or 1.5 million people, without any jobs at all.

Among young workers under twenty-four, many of whom were about to be recruited into the CCC, the numbers were often double the general figure. African-Americans, traditionally “the last hired and first fired,” were also among the hardest hit. In Pittsburgh, the black unemployment rate was near 50 percent, and 43 percent of black families were on the relief rolls. In Philadelphia, black Americans constituted 13 percent of the city’s population but about 33 percent of those on relief in 1932. But relief assistance in the city, faced with unprecedented demand and reduced funds, was providing only 20 percent of what had been given on a per capita basis in 1928.

This matter of relief assistance was about to undergo major changes in the 1930s. Traditionally, relief for the indigent and needy in Pennsylvania had come from private charity groups and was given in kind—food and fuel benefits especially. There was also a small amount of public relief, administered by the state’s 425 local boards of assistance. When unemployment was relatively low, relief was generally given only to “unemployables”—the aged, the infirm, and the caregivers of dependent children. Potential recipients would have to be investigated by case workers for worthiness and then provided supervised assistance in managing their meager resources.

But with the economic catastrophe of the 1930s, the numbers of people in need exploded and now included growing numbers of “employables” as well. By 1932 two million of the state’s nine million people, were receiving some kind of relief, the highest totals in the country. The private charities in Philadelphia even tried some creative experiments in providing work relief that year but found it to be about three times as expensive as giving relief in kind and productively inefficient as well. Sherman Kingsley, the executive director of the Welfare Federation of Philadelphia, sniffed to Governor Pinchot that some of the unskilled people reporting to work relief projects did not even have “proper clothing.”

The need for assistance was so great that by the summer of 1932 the Philadelphia Committee on Unemployment Relief, set up in 1930 to coordinate private charity assistance, had to disband when it ran out of funds to disburse, including the $5 million in public funds granted to it by the city and the state. This collapse of relief in the city left some 57,000 families in the city with no help at all; some reportedly lived on dandelions. This was happening in Philadelphia, the third largest city in the country—Philadelphia, “famed for its quiet wealth, its good food, its day-time naps and its savage conservatism.” A similar organization in Pittsburgh, the Allegheny County Emergency Association, set up in 1931, also had to disband in 1932 for lack of resources.

In some parts of the state cases of tuberculosis and pellagra were doubling. Forty percent of the state’s school children were reportedly suffering from malnutrition, and in some counties in the southwestern part of the state many children were eating only every other day. Thousands of coal miners, evicted from company housing after a strike against conditions so desperate that they staged it in the slack demand summer of 1931, were reportedly living, three or four families to a room, in hillside shacks, subsisting on weed roots. In 1933, workers all over the state in textile manufacturing and coal mining began staging grassrooted wildcat strikes, often in the face of established union leadership opposition. It is impossible to analyze the causes of these 1933 strikes in isolation from the new hope the Roosevelt administration, especially its National Recovery Administration, had kindled in desperate people. On the other hand, without the desperation caused by the Depression, there would have been no fear of lighting the dangerous emotion of hope in the first place.

When the New Deal’s Harry Hopkins sent investigators from the newly established Federal Emergency Relief Administration into the state in 1933, they found woeful deficiencies in Pennsylvania’s relief system. There was inefficient distribution of food, clothing, and fuel and widespread resentment by workers throughout the state of local relief boards that were dominated by the wealthy and employer classes. Lorena Hickock described the unemployed in Pennsylvania as “right on the edge” in a mood that would not take much more to make communists out of them. With such a Dickensian pall spreading everywhere in the state and no hopeful solutions in sight, it is no wonder some feared that a “Red Menace” might spread.

The patent inability of charities or local governments across the country to meet the unprecedented need for assistance was leading some to look to state governments for help. While still governor of New York, Franklin D. Roosevelt led the way, setting up a Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA) in 1931 and appointing Harry Hopkins, a former social worker from Chicago, as its head. Both Hopkins and his chief firmly believed in the superiority of work relief over direct grants of goods or cash, and the TERA did set up some small-scale work relief projects. One such project involved entraining unemployed young men from New York City up to Bear Mountain for some forestry work. The considerable additional expenses involved in setting up these work projects, however, prevented them from becoming more than interesting previews of later New Deal programs like the CCC and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

<insert figure 4—Roosevelt and Pinchot—near here>

Governor Pinchot was not far behind in involving his state government in the deepening relief crisis in Pennsylvania. In November 1931 he began exchanging ideas with other governors about the problems they all faced. He then called the Pennsylvania legislature into special session (he would do this again in 1932 and 1933) and prevailed upon them to appropriate $10 million of state money for relief. Pennsylvania thus became the third state in the country (behind New York and New Jersey) to bring this new kind of state assistance to local relief efforts. To provide for more effective distribution of this money, the legislature in 1932 reorganized the whole system of public relief in the state. A State Emergency Relief Board (SERB) was set up with Eric Biddle of Ardmore as its first director, and it was now charged with distributing state relief money to local emergency relief boards in the counties.

Like Roosevelt, Pinchot used some of the limited state relief money for small-scale work relief projects. One program set up six work camps for housing some of the 25,000 unemployed men put to work for the Highway Administration, yet another sneak preview of the CCC idea. The state National Guard and the Health Department set up these tent camps, each of which housed between seventy and ninety men. Unlike the later CCC camps, these were integrated, with blacks and whites living and working together. The number of applicants far exceeded the positions, and men lined up well before dawn on registration days. Those rejected often left in tears. The lucky ones were given thirty days’ work and army surplus clothing. The three meals a day the men received resulted in reported weight gains of between five and fifteen pounds.

Pinchot also anticipated the CCC in seeing the woods of Pennsylvania as assets in the attempt to alleviate distress and unemployment. The state Department of Forests and Waters employed 1,100 men to cut 10,000 cords of free firewood for needy families. The men also were engaged in other forestry projects in return for food relief.

Despite this unprecedented state involvement in relief matters, Pinchot realized that the needs were beyond what budgetary and political realities in Pennsylvania could provide. He consequently became one of the earliest and loudest voices in the country for federal relief assistance. He sent a public letter to President Herbert Hoover on August 18, 1931, asking for federal assistance on relief, and he followed the letter up with speeches on the subject in Detroit, Cleveland, and Washington.

Unfortunately, Hoover’s ideological rigidity prevented him from formulating any imaginative policy initiatives to combat the Depression. He had, somewhat reluctantly, in 1932 agreed to the establishment of a Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which was later empowered to make loans to states. Pinchot was able, with the expenditure of much energy, to wheedle $30 million in loans from the RFC for distribution by the SERB, but he was pushing up against Pennsylvania’s constitutionally fixed debt limits and was frustrated by Hoover’s refusal to provide grants to the states.

By the time Roosevelt took office in 1933, state resources in Pennsylvania were stretched to the limit, no more aid was coming from Washington, and desperation was deepening among Pennsylvania’s unemployed. Pennsylvania had to weather the winter of 1932–33 with no additional funds until the establishment in May 1933 by President Roosevelt of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), with Harry Hopkins in charge. The FERA was empowered to give grants to the states, and Pennsylvania would receive $196 million from this agency before it was abolished in 1935 and replaced by the federal work relief projects of the WPA, also headed by Hopkins, and the Social Security Administration, which continued the federal subsidies to the states for assisting the unemployables. The creative energy of the New Deal, as expressed in these programs as well as the CCC, was happily greeted throughout the state and resulted in major political shifts.

<1> The Political Scene

The major theme of Pennsylvania politics from the Civil War era down to 1934 is a simple one of Republican Party domination. Democrats were able to elect only one governor in all that time and no United States senators. Republicans also carried the state in all the presidential elections except 1912, when the ex-Republican, Theodore Roosevelt, managed to win a plurality of the vote in a three-way race with William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson. In the two major cities, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, the story was a similar one of long-lived Republican Party hegemony. The party’s strengths were rooted in Civil War memories, a large population residing in small towns and on small farms, and an organization that had grown up symbiotically with the big business interests of the state and had learned to tap those interests for whatever campaign funds were needed.

The Democratic Party of the state, in the words of one scholar of the subject, “barely existed” by the 1920s. In the gubernatorial election of 1926 it failed to carry even one of the state’s sixty-seven counties. In some places, like Philadelphia, it was a “kept” party, kept around by Republican bosses by means of minor patronage and rental payments on its offices as a means of insuring the nomination of eminently beatable candidates and useful allies. But the times, they were a-changing.

The Depression, and the widespread perception that Hoover was both unable and unwilling to deal with the problems of mass suffering and insecurity, would provide the Democrats with an opening—if they could seize it and run with it. Electoral success for the party was almost guaranteed in 1932, no matter whom it ran against Hoover, but continued success would demand bold and imaginative departures from the conservative leadership the national party had reverted to in the 1920s. The electoral coalition the Democrats created in the turbulence of the Depression would be a precarious one and one that would have to be exploited with creative intelligence and compassionate rhetoric. Once created, however, it would provide the party with a “permanent majority” that would endure for almost two generations until the white south began to slip away in the 1960s.

The man at the center of this political opportunity for the Democrats was, of course, Franklin D. Roosevelt, often considered the greatest president of the twentieth century. Looking back at Roosevelt from the vantage point of the 1960s, the high noon of twentieth-century liberalism, several New Left historians found him seriously wanting in his commitment to liberal change. Looking back at Roosevelt, however, from the vantage point of this writing, through the denser atmosphere of the “Twilight of the Left,” assessments of his achievements are bound to be more friendly. More important, if we try not to look backward at Roosevelt at all, but rather forward with him and the country from 1932 onward, we can perhaps regain a sense of the impressive achievements of his presidency and the indispensable contributions of Roosevelt himself. And nowhere else was his contribution more central than in the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

It is important to remind ourselves of the intense emotions that Roosevelt evoked from his contemporaries, ranging from conservative denunciations of “That Man” to the kind of adulation he inspired in his supporters. One of these stalwart supporters was Senator Joseph F. Guffey, one of Pennsylvania’s leading Democrats, who later wrote of him: “I probably saw him as often as anyone. . . . I can only say that in a long and busy lifetime I have never known a greater man, and in the perspective of the years his shadow grows longer as his stature becomes more clearly perceived.” Most of the men who served in the CCC would not argue with Guffey’s assessment.

Roosevelt and his New Deal had an even more profound impact on the Democratic Party in Pennsylvania than did the Depression. After all, even with unemployment soaring in the state after 1929, Republicans still managed to elect Pinchot in 1930, maintain majorities in both state houses, elect David Reed as United States senator in 1932, win twenty-three of the state’s thirty-four congressional seats, and carry the state for Hoover that same year. The Democrats in Pennsylvania had a difficult upward climb ahead of them.

A pivotal figure in this Democratic story is, curiously, the Republican Gifford Pinchot. As an old Bull-Moose Republican and an ardent conservationist, Pinchot’s ideological orientation was very different from the laissez-faire conventional wisdom of the triumphal Republicans of the 1920s and closer to that of the two Roosevelts. Moreover, Pinchot and Franklin Roosevelt were linked by personal friendships. The friendship of their wives, Eleanor Roosevelt and Cornelia Bryce Pinchot, was even older, dating from their childhoods.

Pinchot formally remained a Republican in the 1930s, and his relationship with Democrats proved complex and prickly. He welcomed Roosevelt’s national policies on relief and appreciated the support the president urged on Democratic state legislators for his own program in 1933. He also cooperated with the Democratic State Committee in the early months of the CCC in helping them get foremen positions in the camps. But when his term was nearing its end in 1934, he engaged in some serio-comical negotiations with state Democrats in the hopes of running for United States senator on a ticket with George H. Earle, the Democratic candidate for governor that year. These hopes were dashed by a bitter dispute that erupted between Pinchot and Joseph F. Guffey, who coveted the Senate seat for himself.

Guffey’s election to the Senate in 1934 effectively ended Pinchot’s political career. Pinchot made futile efforts to receive the Republican presidential nomination in 1936 and to regain his old governor’s seat in 1938, but his health was not good. He suffered from shingles and a series of heart attacks in 1939 weakened him until, at last, he died of leukemia on October 4, 1946.

Meanwhile, the New Deal had an immediate impact on Pennsylvania’s economy, which translated into unprecedented success for the Democrats in the 1934 elections. Thanks to successful relief programs, including the CCC, the FERA, and the Civil Works Administration (CWA), not only did Guffey become Pennsylvania’s first Democratic senator but George Earle became only the second Democratic governor since the Civil War. The stage was set for Pennsylvania’s “Little New Deal” in the middle years of the decade. Roosevelt’s New Deal had played the most important role in this revival of the state’s Democrats, and the CCC was one of the most popular of its programs contributing to that revival.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.