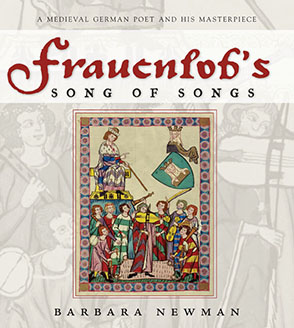

Frauenlob's Song of Songs

A Medieval German Poet and His Masterpiece

Barbara Newman

“The need for a readable Frauenlob translation has existed for a long time. Now, consistent with her reputation as one of the preeminent scholars in the field of medieval studies, Barbara Newman has produced that translation, capturing the vibrant spirit of the Marienleich in clear, lively English.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Barbara Newman, known for her pathbreaking translation of Hildegard of Bingen’s Symphonia, brilliantly captures the fervent eroticism of Frauenlob’s language. More than the mother of Jesus, the Lady of Frauenlob’s text is a celestial goddess, the eternal partner of the Trinity. Like Christ himself she is explicitly said to have two natures, human and divine. Frauenlob lets the Lady speak for herself in an unusual first-person text of self-revelation, crafted from the Song of Songs, the Biblical wisdom books, the Apocalypse, and a wide array of secular materials ranging from courtly romance to Aristotelian philosophy.

Included with the book is a CD recording of the Marienleich by the noted ensemble Sequentia, directed by Benjamin Bagby and the late Barbara Thornton. The surviving music is the composer’s own, reconstructed from fragmentary manuscript sources. Accompanying Newman’s translation is a facing-page edition of the German text, detailed commentary, and a critical study presenting the most thorough discussion to date of Frauenlob’s oeuvre, social context, philosophical ideas, sources, language, music, and influence. Rescuing a long forgotten medieval masterpiece, Frauenlob’s Song of Songs will fascinate students and scholars of the Middle Ages as well as scholars, performers, and connoisseurs of early music.

“The need for a readable Frauenlob translation has existed for a long time. Now, consistent with her reputation as one of the preeminent scholars in the field of medieval studies, Barbara Newman has produced that translation, capturing the vibrant spirit of the Marienleich in clear, lively English.”

“This is a book intended for all those mature enough in their appreciation of beauty to stomach the strong wine of two of the Virgin Mary’s most sophisticated devotees. Heinrich von Meißen’s Marienleich offers the reader a scintillating yet mysterious vision of Mary as the goddess of the heavenly Jerusalem; Newman’s translucent commentary on, introduction to, and translation of the poem unlocks its mysteries as only a consummate lover of theology, history, and poetry can. The combination is a treat to be savored, rolled over on the tongue until its complexity gives forth its astonishing sweetness.”

“Frauenlob’s Song of Songs is a gorgeous publication, clearly and forcefully written, stunningly laid out and carefully edited. . . . It comes with all the scholarly trappings, but also with a CD of a beautiful, hour-long recording of Heinrich’s composition, essential to appreciating this song.”

“Scholars from many disciplines will surely find this delightfully well-written book stimulating. I believe that it will be accessible and interesting to students as well. The outstanding scholarly apparatus (commentary, glossary, indices, full bibliography) intensifies the book’s usefulness as a textbook by simplifying ease of understanding and access to learned and biblical allusions.”

Barbara Newman is Professor of English, Religion, and Classics at Northwestern University. She is the author, most recently, of God and the Goddesses: Vision, Poetry, and Belief in the Middle Ages (2002). She also published a critical edition and translation of Hildegard of Bingen's Symphonia (1988; rev. ed. 1998).

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

About the Text, Translation, and Recording

Marienleich / Frauenlob's Song of Songs: Text and Translation

1. The Performer, His Public, and His Peers

2. Frauenlob’s Canon

3. The Marienleich in Context

4. The Marienleich as a Work of Art

5. Reception and Influence

Commentary on the Marienleich

Glossary of Technical Terms

Abbreviations

Bibliography

Index

Chapter 1:

The Performer, His Public, and His Peers

The poet-composer Frauenlob, a contemporary of Meister Eckhart and Dante, enjoyed a public career spanning four decades, with patrons in the great courts of central and northern Europe. When he died in 1318, his reputation was so great that he was buried in the cloister of Mainz Cathedral. According to the chronicler Albrecht von Strassburg, “on the vigil of Saint Andrew [November 29] in the year 1318, Heinrich, called Frauenlob, was buried in Mainz, in the cathedral cloister near the school, with exceptional honors. Women carried him from his lodgings to the sepulchre with loud lamentation and great mourning, on account of the infinite praises that he heaped on the whole feminine sex in his poems. Moreover, such copious libations of wine were poured on his tomb that it overflowed throughout the entire cloister of the church. He composed the Cantica canticorum in German, known in the vernacular as Unser Frowen laich, and many other good things.”

After death, Frauenlob remained an influential figure, much admired and imitated up to the time of Hans Sachs two and a half centuries later. He is among the poets anthologized in the illuminated Manesse Codex, and one of only a handful of medieval German composers whose music comes down to us. Around 1364, the humanist John of Neumarkt sent the archbishop of Prague a Latin prose translation of one of Frauenlob’s poems, praising him as tantus et tam famosus dictans and vulgaris eloquencie princeps, in much the same terms as he lauded Petrarch. But in spite of his fame, these testimonies tell us most of what we know about Frauenlob apart from the manuscripts of his poems. His output was very large, yet the precise contours of his canon are unknown and probably always will be, since a great many texts composed by the “school of Frauenlob” were transmitted under the master’s name. In fact, fully two-thirds of the strophes ascribed to him survive in a single manuscript each. Aside from the well-known Cantica canticorum (or Marienleich) presented here, there is little overlap.

The meistersingers, who revered Frauenlob, maintained that he had founded the first “singing school” in Mainz, where he spent the last years of his life. Although this tradition cannot be verified for lack of evidence, it seems to have arisen early, for the illustration of the poet in the Manesse Codex (ca. 1340) shows him teaching at just such a school. In this painting (fig. 1), Frauenlob presides from a lofty chair at an outdoor music lesson or performance. Over his striped tunic he wears a cloak of ermine and a coronet trimmed with the same fur, usually reserved for high nobility but here representing the gift of a particularly lavish patron. With his right hand raised in a stylized teaching gesture, the singer-poet holds in his left what looks—anachronistically—like a conductor’s baton. On a carpet below, stretched out by a piper on the right and a drummer on the left, a fiddler performs while other musicians listen, holding a variety of soft and loud instruments including flute, psaltery, and shawm. The meister’s identity is confirmed by a symbolic coat of arms representing his Lady, the crowned Virgin, who extends her mantle over his shield in a gesture of protection and favor. This painting immediately precedes the text of the Marienleich and reminds us that the German leich had always been an instrumental genre. Frauenlob’s great poem was undoubtedly meant for the kind of lavish musical performance illustrated here, although—as is usual with medieval music—the manuscripts record only the vocal melody. Instrumental parts would have been composed or improvised by the performers, as they are by Sequentia in the CD that accompanies this book.

<Figure 1 about here>

A few folios earlier in the Manesse manuscript, Frauenlob appears in a very different role. This painting (fig. 2) introduces the poems of his archrival, Regenbogen, who was held to have been a smith and appears in his forge with hammer, anvil, and tongs. (The belief derives from a line in one of his poems; it may or may not have been literally true, since “forging” was also a favorite metaphor for crafting poetry.) Next to Regenbogen sits Frauenlob, sporting the same light beard and zigzag-striped tunic as in the Singschule illustration, but he no longer wears his honorific fur mantle. Instead, both poets, decked with identical garlands, raise their hands in aggressive, symmetrical gestures of debate. Regenbogen, prepared to wield his hammer at need and seconded by an apprentice with bellows, occupies the position of strength. In contrast to the musicians’ scene, which flaunts the high honor Frauenlob enjoyed, this painting suggests the other side of his reputation as a controversial figure, one whose pride and ostentatious mannerism aroused resentment and criticism. The grounds of Frauenlob’s feud with Regenbogen are now hard to ascertain, given the thorny problems of authentication. But the two poets belonged to a literary culture in which fierce competition constituted a genre unto itself—the Sängerkrieg, or “singers’ war”—so the legend of their rivalry lived on after their deaths in a fictional work, Der Krieg von Würzburg (The Battle of Würzburg). In this text the two rivals come forth to fight as champions in a tournament, with Frauenlob defending the honor of women, and Regenbogen proclaiming the superiority of men. Although their debate ends in a draw, this fictional portrait shaped both singers’ reputations for centuries to come.

<Figure 2 about here>

<1> Patrons, Peers, and Polemics

Frauenlob is the most famous of a neglected group of poets who fill a key place in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century literature. Traditionally named Spruchdichter—an umbrella term for “lyric poets who were not minnesingers”—these itinerant artists have more recently been characterized as “poet-minstrels.” Their repertoire, called Sangspruchdichtung, comprised sung poetry on a variety of subjects, religious, political, and moral; but this is more properly a sociological term than a generic term. Unlike minnesingers, who were for the most part noble amateurs, the Spruchdichter were professional traveling minstrels, usually of bourgeois origin, who embraced the arts of poetry and song as a vocation rather than as a polite accomplishment. Since they made their living by their art, contemporaries called them singers who “took guot for êre,” that is, received payment in money and kind for the praise of their patrons. The term was not always a pejorative one, although in the sermons of friars it took on a disapproving tone. Normally, the willingness of nobles to support such traveling artists (if all too scantily in material terms) shows how highly they valued them for both the prestige and the entertainment they could offer. In contrast to France, where a class distinction separated the noble poet-composers (troubadours or trouvères) from the more plebeian musicians (joglars or jongleurs) who traveled from court to court performing their songs, the Spruchdichter filled both roles—nor was the art of performance seen as demeaning, except by clerical moralists. A rare biographical notice on Frauenlob mentions that one of his patrons, Duke Heinrich von Kärnten, in 1299 gave him the lordly sum of fifteen marks to buy a horse. The Latin manuscript describes the poet as an ystrioni dicto Vrowenlop—“an entertainer called Frauenlob.”

A horse was a necessity in his line of work, since the instability of the political situation—and the performer’s need for ever-new audiences—required constant travel. Unlike such fourteenth-century court poets as Geoffrey Chaucer, Frauenlob and his German contemporaries could not expect stable long-term patronage, but moved frequently, settling for a time at any court where they found a warm welcome and a solvent prince. This itinerant lifestyle was a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it rendered poet-singers marginal and highly suspect to the arbiters of morality. Like goliards, or wandering students, they traveled too much to be trusted, for they seldom stayed in one place long enough to become permanent members of parishes, households, or other stabilizing institutions. If accused of any crime, they lacked local family connections and long-term acquaintances to vouch for them. On the other hand, the minstrel’s wandering ways enhanced his value to his patrons. Court records and account books show that, when they were not performing, poet-minstrels filled a variety of useful and remunerative roles as messengers, heralds, watchmen, interpreters, and spies. Well-traveled, versed in a range of dialects, and welcomed by all social strata, such performers could be skilled information-gatherers. A poet as learned as Frauenlob might even have placed his clerical skills at his patrons’ service—for example, in reading and transcribing letters—but this must remain conjectural, given the frustrating lack of documents on the lives of individual Spruchdichter. Finally, at important festivals, such as knightings, weddings, and coronations, a seasoned entertainer would be given the role of “minstrel king,” responsible for devising ensemble performances and serving as master of ceremonies. This is another possible interpretation of Frauenlob’s role in the Manesse illustration.

We know the identity of his lords almost exclusively from the poems he wrote in their honor. In addition to Heinrich von Kärnten, Frauenlob’s patrons included Duke Heinrich IV of Breslau in Silesia (d. 1290); Count Otto II von Oldenburg (d. 1304); Archbishop Gieselbrecht of Bremen (d. 1306); Count Otto III von Ravensberg in Westphalia (d. 1306); Count Gerhard von Hoya in Lower Saxony (d. 1311); Duke Heinrich (I or II) von Mecklenburg; Margrave Waldemar von Brandenburg (d. 1319); Prince Wizlav von Rügen (d. 1325); a Danish king, probably Erik VIII (d. 1319); and finally, Peter von Aspelt, archbishop of Mainz (d. 1320). Unfortunately, we cannot trace the chronology of the singer’s wanderings before his final decade, much less establish a biography, for his poems mention few datable events. But among those few are a feast of Rudolf of Habsburg, held in 1278 to celebrate his victory over the Bohemian king P_emysl Ottokar II, and the knighting in 1292 of Ottokar’s successor, Wenceslas II. Frauenlob also composed lamentations on the death of Rudolf in 1291 and Wenceslas in 1305. Given these Bohemian connections, most scholars believe he spent some time at the court of Prague, probably at the beginning of his career. His birthplace of Meissen in Saxony was not far from Bohemia, and the allure of that glittering court would have made it a natural magnet for an ambitious young singer.

That Frauenlob was an ambitious young singer is clear from an interesting polemic against him, couched in the form of ironic praise. Echoing twelfth-century Latin satire against “beardless masters,” an anonymous critic writes:

<L/L; 2 cols.>

Wa bistu gewest zu schule, Where did you go to school,

daz du so hohe bist gelart? that you acquired such great learning?

man sprichet dich also kindes, They say you are such a child

daz in der niuwe si din bart. that your beard is still new.

drizehen jar der hastu noch nicht, You are not yet thirteen years old—

nu la dich got vierzehen mit eren leben. now may God grant you to live fourteen years with honor!

Du macht uf meisters stule You may well sit in the master’s chair,

gesitzen wol, des höre ich jehen, so I hear people say;

unt daz von dinen jaren and [they say] that no one your age

nie din geliche wurde gesehen. was ever seen to be your equal.

wol dir der seldehaften schicht, Lucky you that, on account of this fortunate tale,

daz nu din pris so ho beginnet sweben. your praise now begins to soar so high!

<1/2 line space>

Man gicht, in diutischem riche They say that in the German realm

si niender phaffe din genoz no priest is your equal,

noch singer din geliche. nor is there any singer like you.

und macht du daz bewisen, If you can prove this—

daz dir da her von himele vloz namely, that wisdom flowed down from heaven

unde in din herze sich besloz and enclosed itself wholly in your heart—

die wisheit gar, vür war, this indeed is deserving of praise!

daz muz man prisen.

(GA VII.42G)

<end L/L>

The skeptical or jealous or—just possibly?—admiring author of this strophe compares the precocious Frauenlob to Jesus at the age of twelve, who amazed the rabbis of Jerusalem with his wisdom (Luke 2:42–48). According to appreciative rumors, says the satirist, there was not only no singer but also “no priest” to equal the young poet’s wisdom “in the German (diutischem) realm,” a phrase that sounds teasingly like “the Jewish (jüdischem) realm.” So this poem, which must have been written early in Frauenlob’s career, indicates that he chose the life of traveling poet while still quite young (eighteen perhaps, if not twelve) and quickly gained a reputation for theological learning.

We cannot definitively answer the satirist’s question “Where did you go to school?” But the likeliest guess is the cathedral school at Meissen, where the novice poet would have obtained a thorough grounding in the liberal arts and in theology. His title of meister does not mean that he earned the degree of magister artium, for the oldest university in the empire (Prague) was founded only in 1348. Vienna, Heidelberg, and Cologne followed later in the fourteenth century. Nevertheless, meisterschaft in the double sense of learning and artistic skill was crucial to the self-image of Frauenlob and his peers, who sometimes used the term as a near-equivalent for magisterium, the teaching authority of the church. The Spruchdichter were the German vernacular theologians of their age, dwelling by choice on the Trinity, the Incarnation, the glories of the Virgin, the marvels of nature, and other philosophical and religious themes. Frauenlob himself was instrumental in creating a vernacular lexicon for the terms of Platonic metaphysics and Aristotelian logic, playing a key role as well in the German reception of such twelfth-century masters as Alan of Lille. A meister denoted both a master craftsman and a wise teacher: to sing meisterlich and with wîsen sinn (wise sense) was the thirteenth-century artistic ideal from which the later meistersingers derived their self-concept. When they celebrated great poets of the past, they tended to list precisely twelve “old masters” by analogy with the apostles—although two of Frauenlob’s contemporaries composed sly lists of eleven, leaving their listeners to identify the present singer as the twelfth.

Meisterschaft in Frauenlob’s own poetry describes such phenomena as the skill of the artist; the ennobling power of woman’s love (VII.35.18); the creative bounty of the First Cause (VII.9.4); and above all, the mastery of God. In the Incarnation, he sings, Christ aventiurte meisterschaft von vremder craft (I.14.22): “he embarked on an adventure that risked (or revealed) his mastery against (or over) an alien power.” By his victory he proved himself the ultimate craftsman: der meister heizet meister, “let the Master be called a master indeed!” (I.14.14). The poet’s personal mastery likewise stems from God, for artistic inspiration is a divine gift. In response to contemporaries who lamented that the golden age of art was over, Frauenlob proclaimed defiantly that singers of his own day are in no way inferior to those of the storied past, for creativity is inexhaustible as the force of nature:

<L/L; 2 cols.>

Prüft regen mit den winden: Consider the rain and the winds!

die han hiute also groze kraft They have as much power today

von gotes haft by God’s covenant

als über zwei tusent jare. meisterschaft as two thousand years ago. So too

si dar gebogen. with mastery in art.

(VI.12.6–10)

<end L/L>

Frauenlob knew the songs of some of the great minnesingers, especially Walther von der Vogelweide, but he was more deeply influenced by the generation of Spruchdichter preceding him, in particular Hermann Damen, Reinmar von Zweter, and Konrad von Würzburg. Damen (d. ca. 1300) was not himself a major talent, but he was once thought to have been Frauenlob’s teacher on the basis of four illuminating strophes he directed to the younger poet. One of these addresses Frauenlob by name, while the others appeal to an unnamed “child.” Like the satirist cited above, Damen chastises the youthful poet for his arrogance. Although still “a child in childish years” (ein kint in kindes jaren), he already presumes to write about all the wonders of creation—Waz dem himel obe unde unde / si und in abysses grunde (“Whatever may be above and beneath the heaven, and in the depths of the abyss”). Moreover, he boasts shamelessly, professing to surpass “the art of all singers” living and dead—a charge based on a notorious song of self-praise that, as we shall see, was probably the work of a malicious parodist. But if it was, Frauenlob must already have earned a reputation for overweening pride, or else such a parody could never have fooled colleagues who knew him. Hence Damen counsels the young singer to learn some humility by apprenticing himself to a more seasoned poet:

<L/L; 2 cols.>

Durch vriuntschaft unt durch guot, Out of friendship and kindness,

wend ich dir guotes vil wol gan. I hope much good will come your way.

vür war, sus stet min muot: Truly, this is my offer:

waz ich dir guotes lernen kan, whatever good I can teach you,

des wil ich weinic sparen. I will withhold none of it.

Dunkstu aber dich so here, But if you think so highly of yourself

daz dir tüge niemans lere, that no one’s teaching is of use to you—

daz wirt dines herzen swere, that will be a burden on your heart

wiltus nicht bewaren. if you do not wish to guard it.

<end L/L>

Frauenlob left us a single appreciative line about Damen, so he seems not to have resented this fatherly offer. But it is most unlikely that he accepted it, since he was to choose an artistic path that was quite different from the older poet’s didactic plain style.

Damen’s strophe addressing Frauenlob by name is of special interest because it sheds some light on the poet’s sobriquet. Like performing artists today, many traveling minstrels adopted stage names. The roll call of these poets includes such flamboyant characters as Der Helleviur (Hellfire), Der Marner (the Steersman), Der Unverzagte (the Undaunted), Regenbogen (Rainbow), Singuf (Sing Out), Rumelant (Land of Praise), Der tugendhafte Schreiber (the Virtuous Scribe), Suchensinn (Seek the Sense), and Muskatblut (Nutmeg). Since Frauenlob was still a “child” at the time Damen addressed him, he must have chosen his own sobriquet at the outset of his career, leading rivals to speculate on the reason for it:

<L/L; 2 cols.>

Vrouwenlob, des hastu scande. Frauenlob, this [boasting] is shameful!

vrouwen lob in scanden bande The praise of ladies in a fetter of shame

stuont nie halben tac zuo phande. will never stand as pledge for half a day.

merken diz beginne, Consider this for a beginning:

Wie vil eren habe der name! how much honor there is in the name!

vrouwen lob in eren krame The honorable praise of ladies

spilt vil schone sunder schame plays beautifully without disgrace

nach heiles gewinne. and profits toward salvation.

Uns tuot her Reimar kunt, Herr Reinmar tells us

der vrouwen lob si reinez leben. that praise of ladies is a pure life.

du triffs der selden vunt, You have hit upon the fount of blessings

ist dir der name durch daz gegeben; if this is the reason for your name;

so soltu vrouwen minne so you should extol the love of ladies

Prisen und ir wibheit eren and honor their womanhood

und ir lob mit sange meren. and enhance their praise with song.

wil dir ieman daz vurkeren, If anyone dissuades you from this,

daz kumpt von unsinne. it comes of foolishness.

<end L/L>

Not unreasonably, Damen assumed that “Frauenlob” meant vrouwen lob, the courtly praise of ladies, so he advised the young poet to adopt the idiom of traditional minnesang instead of busying himself with the mysteries of divinity and natural science. But this, it turns out, is precisely what Frauenlob did not wish to do—for it was the Ewig-Weibliche, the Feminine as a cosmic principle, that he truly loved. To honor Woman in the style he intended, he needed not to abandon but to immerse himself ever more deeply in the mysteries that Hermann Damen would have had him.

Reinmar von Zweter (d. ca. 1260), cited in Damen’s cautionary poem, is the second singer who demonstrably influenced Frauenlob. This prolific blind poet, a native of the Rhineland, grew up in Austria and served a number of patrons, including Duke Leopold VI of Austria and King Wenceslas I of Bohemia (reg. 1230–53) in the early years of his reign. It may well have been in Prague, a generation later, that Frauenlob encountered his songs. Reinmar composed some 229 strophes of Spruchdichtung, but it is his religious leich that Frauenlob most clearly echoes, though the debt has been little noticed. Reinmar’s innovative leich praises the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Virgin as linked manifestations of Minne (personified Love), using the “crossover” mode that enjoyed immense pan-European popularity in the mid-thirteenth century. The imperious feminine figure of Minne fuses with her Latin counterpart, Caritas, linking the tropes of courtly love with a tradition of Song of Songs exegesis and religious allegory nurtured by such twelfth-century greats as Hugh of St.-Victor and Bernard of Clairvaux. A similar convergence between God and Frau Minne can be seen in many of Reinmar’s contemporaries, including the Netherlandish mystical minnesinger Hadewijch, as well as the beguine Mechthild von Magdeburg and the Franciscan poet Lamprecht von Regensburg, a director of nuns. It is in this tradition that Reinmar sings:

<L/L; 2 cols.>

Des vater Minne unt ouch des suns The Love of the Father and the Son

der gotheit in ir herze dranc urged the heart of the Godhead

unt clagte in beiden, wie daz uns and lamented to both of them

der êrste val ze valle twanc: how the first Fall compelled us to fall

dar an uns allen misselanc. and brought us all to grief.

Got hêrre unüberwundenlich, O God, invincible Lord,

wie überwant diu Minne dich! how Minne has vanquished you!

getorste ich sprechen, sô spraech ich: If I dared speak, I would say,

“si wart an dir sô sigerîch, “she won such a victory over you

daz si den val nam über sich.” that she took the Fall upon herself.”

<end L/L>

Minne, the love that galvanizes Father and Son into action, turns out to be another name for the Holy Spirit: “Der minne schenke ist aller meist / der übersüeze Gotes Geist: / dem er die wil schenken” (“The gift of Love is above all the Spirit of God, surpassingly sweet to whomever he will give her”). It is through Minne that God becomes incarnate:

<L/L; 2 cols.>

Durch minne wart der alde junc, Through Love the Old One became young,

der ie was alt ân ende: he who was forever ancient without end:

von himel tet er einen sprunc from heaven he made a leap

her ab in diz ellende, into this exile here below.

ein Got unt drî genende One God and three persons

Enphienc von einer meide jugent, received youth from a maiden!

daz geschach durch minne: It was through Love that this happened.

ir gap des heilegen Geistes tugent The virtue of the Holy Spirit gave her

minnebernde sinne: senses made fruitful by Love:

des wol dir, küniginne! therefore, Queen, you are blessed!

<end L/L>

Frauenlob similarly links the Virgin, the Holy Spirit, and an all-powerful Minne who transforms the ageless God into a youthful lover or a newborn babe. Reinmar was by no means his only source for these motifs, but Frauenlob’s many verbal echoes of his Leich reveal a deep respect for him.

Konrad von Würzburg, the most influential of Frauenlob’s precursor poets, has lately been recognized as “the single most versatile and prolific [German] author of the thirteenth century.” He traveled widely, visiting France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands as well as German courts, and eventually settled in Basel where he is buried. Unlike most of his peers, Konrad composed in multiple genres including minnesang, brief tales (märe), hagiography, epic, and courtly romance, in addition to the religious and political lyrics that were the staple of wandering poets. Like Reinmar, he also composed a religious leich, which Frauenlob undoubtedly knew, but his most famous work was Die goldene Schmiede (The Golden Forge), an elaborate Marian praise-poem of two thousand lines, extant in more than thirty manuscripts. A pioneer of the geblümter Stil, or “flowery style,” which Frauenlob would carry to hitherto unimagined heights, Konrad introduced the floral lexicon of this new aesthetic into the modesty preface of Die goldene Schmiede, where he laments his inability to weave Mary the garland she deserves:

<L/L; 2 cols.>

er muoz der künste meienris He who would braid and decorate

tragen in der brüste sin, your noble chaplet with flowers

swer diner wirde schäpelin must bear within his breast

sol blüemen unde flehten, the blooming May-branch of the arts

daz er mit roeselehten in order to adorn it

sprüchen ez floriere, with rose-red phrases

und allenthalben ziere and decorate it all around

mit violinen worten, with words like violets,

so daz er an den orten to purify it utterly

vor allem valsche ez liuter, of everything false,

und wilder rime kriuter and most beautifully interweave

darunder und da’nzwischen the herbs of exotic rhymes

vil schone künne mischen beneath, around, between

in der süezen rede bluot. the blossoms of sweet speech.

<end L/L>

In a lament he composed on Konrad’s death in 1287—his only eulogy for another poet—Frauenlob paid the supreme tribute of complimenting the master in his own terms, fusing the aesthetic tropes of “blossoming speech” and the “golden smithy” in which the artist labors to forge poetic praise. But where Konrad is ornate yet clear, Frauenlob is deliberately hermetic and obscure, recalling the trobar clus, or “closed style,” of some of the Provençal troubadours. His lament for Konrad is in fact a demanding expression of his own aesthetic program:

<L/L; ext indent>

Gefiolierte blüte kunst,

dins brunnen dunst

und din geröset flammenriche brunst,

die hete wurzelhaftez obez

gewidemet: in dem boume künste riches lobes

hielt wipfels gunst

sin list, durchliljet kurc.

<1/2 line space>

Durchsternet was sins sinnes himel,

glanz, als ein vimel

durchkernet. luter golt nach wunsches stimel

was al sin blut, geveimt uf lob,

gevult mit margariten nicht zu kleine und grob;

sins silbers schimel

gap gimmen velsen schurc.

<1/2 line space>

Ach, kunst ist tot! nu klage, armonie,

planeten tirmen klage, nicht verzie

polus jamers drie.

genade im, süze trinitat,

maget reine, entfat:

ich meine Conrat,

den helt von Wirzeburc.

(VIII.26)

<end L/L>

<one line space>

<prose trans. of L/L>

[Exquisite art, decked with blossoming violets! The vapor rising from your fountain and your rose-red, flaming fire have brought forth deeply rooted fruit. In the tree of artistic praise-poetry, his mastery, adorned with twining lilies, enjoys the summit of favor. The heaven of his skill glittered with stars, radiant, firm as a miner’s axe. All his blossoms were pure gold, purged of dross, refined to win praise, according to the goad of his intention—filled with pearls, neither too small nor too coarse. The shimmering of his silver (axe) thrust against rocks to yield jewels. Alas, art is dead! Lament now, music of the spheres! Planetary plowers, lament! Let the heavens triple their outcry! Have mercy on him, sweet Trinity; pure Virgin, receive him. I mean Konrad, the hero of Würzburg.]

<end prose trans. of L/L>

<1> Frauenlob’s Self-Praise: Literary Boast or Malicious Parody?

This mannered style won both admirers and detractors. In his relatively mild censure of Frauenlob’s pride, Hermann Damen had accused him of claiming to surpass not only present rivals, but also the greatest singers of the past, with his superlative artistry. Throughout his life and long afterward, Frauenlob’s reputation labored under the charge of monumental arrogance, resting on a literary boast that rivals those of Homeric heroes. The fabled boasting poem has provoked attacks far more savage than Damen’s, extending well into the twentieth century; but its authenticity has recently and, in my view, convincingly been challenged by Johannes Rettelbach. Yet the poem and the counterattacks it inspired still have a great deal to tell us about Frauenlob’s ambitions, his enemies, and his literary culture—all the more so if the original boast is a forgery. Here is what Hermann Damen and others thought the poet had sung of himself:

<L/L; ext indent>

Swaz ie gesang Reimar und der von Eschenbach,

swaz ie gesprach

der von der Vogelweide,

mit vergoltem kleide

ich, Vrouwenlob, vergulde ir sang, als ich iuch bescheide.

sie han gesungen von dem feim, den grunt han sie verlazen.

<1/2 line space>

Uz kezzels grunde gat min kunst, so gicht min munt.

ich tun iu kunt

mit worten unt mit dönen

ane sunderhönen:

noch solte man mins sanges schrin gar rilichen krönen.

sie han gevarn den smalen stig bi künstenrichen strazen.

<1/2 line space>

Swer ie gesang und singet noch

—bi grünem holze ein fulez bloch—,

so bin ichz doch

ir meister noch.

der sinne trage ich ouch ein joch,

dar zu bin ich der künste ein koch.

min wort, min döne traten nie uz rechter sinne sazen.

(V.115)

<end L/L>

<one line space>

<prose trans. of L/L>

[Whatever Reinmar (von Zweter) and (Wolfram) von Eschenbach ever sang, whatever (Walther) von der Vogelweide ever said—with gilded garments I, Frauenlob, gild their song, as I inform you. They have sung of the froth and left the depths untouched. My art comes from the bottom of the cauldron—so I proclaim. I make it known in words and melodies, without a trace of ridicule: the shrine of my singing ought to be nobly crowned. Singers until now have traveled the narrow path that runs alongside the highway of rich art. Above all who have ever sung and are singing still, I am their master! They are like a rotten stump compared to a living tree. I bear the yoke of artistic skill; I am a master chef of the arts. My words and melodies have never overstepped the bounds of proper meaning.]

<end prose trans. of L/L>

As Burghart Wachinger has noted, this poem is unparalleled in all medieval German literature for its unabashed, extravagant self-praise. Its assertive gesture of self-naming (“ich, Vrouwenlob”) is found nowhere else except in fictional “singers’ wars” like Der Krieg von Würzburg (composed after Frauenlob’s time) and the earlier Wartburgkrieg, which he knew. In that work of dramatic fiction, which presents rival singers competing to produce the best praise-poem, Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach are prominent characters, and it is for that reason likely that the boast cites them. (Otherwise it would have made little sense for Frauenlob to compare himself with Wolfram, a much earlier epic poet, rather than a fellow Spruchdichter.) The “Reimar” of the boast is surely Reinmar von Zweter, although some critics have mistakenly identified him as Reinmar der Alte, a minnesinger who lived a century before Frauenlob but is now more famous than von Zweter. In vaunting his superiority to these precursors, Frauenlob—or the singer impersonating him—boasts of two qualities in particular: that his poetry is more highly crafted (“with gilded garments I gild their song”) and that it has greater philosophical depth (he sings “from the bottom of the cauldron,” as opposed to the superficial froth of others). Both the depth and the verbal ornament are illustrated by a series of self-conscious metaphors—the cauldron of art with its “master chef,” the laureate’s crown, the high road of true song alongside the narrow paths of impostors, the flourishing green tree beside the dead wood of the past. Much of the poem, like the elegy for Konrad von Würzburg, is deliberately riddling and obscure.

The Manesse Codex transmits two counterstrophes attacking this poem, both ascribed to Regenbogen. The first begins with open abuse and proceeds to a passionate defense of the old masters:

<ext>

Braggart, nitwit, fool, idiot—shut up about the art of the dead! My mouth contradicts you; you get no sympathy from me. You claim that you gild the song of the masters with a gilded garment—they who plucked so many roses of skillful invention from the field of art, and still do? I will be the champion of them all! Your art will stumble: I will engrave the cauldron of your notions for you. Your art seems to me more like a nettle than the violets of mastery. How dare you mount the throne of art on which they sat! I come forth as the defender of them all. Whether you believe it or not, I’ll be a shield for them all. My song will strike you right on target, for your boasting annoys me no end. My art will pound you through the cauldron! If the dead and the living leave you free, then try just once to slip out of my fetters! (V.116G)

<end ext>

In a second counterstrophe, Regenbogen ridicules Frauenlob’s esoteric poetry as an “art of the balance and the pumice stone” and mockingly calls for an interpreter to translate it—a plea with which even more appreciative readers can still sympathize. Contrasting Frauenlob unfavorably with Wolfram, Walther, and “the two Reinmars”—in a pointed claim to possess wider poetic knowledge than the author of the boast—his rival declares Frauenlob’s song to be no “gilded garment” but threadbare and “formless as clothes without a waistline.” Yet another counterstrophe, transmitted anonymously in the Jena manuscript, claims that Walther and Reinmar both excelled in the praise of ladies (vrouwen lob), whereas Frauenlob’s dull singing “pours out nothing but fool’s wine.”

Although at least three contemporaries, including Hermann Damen and Regenbogen, responded to the boast as an actual song by Frauenlob, its authenticity has been questioned more than once. Karl Stackmann noted the problem of reconciling its claim to unrivaled mastery with Frauenlob’s exaltation of Konrad, in whom “art itself died.” Beate Kellner points out that in medieval literary culture such boasts are less a function of individual personality than of genre: self-praise is suited to a poetic competition, praise of a colleague to eulogy, and contemporaries would not necessarily have been troubled by a contradiction between them. Rettelbach, however, presents compelling evidence that Frauenlob could not have written the boast, for it contains an elementary technical error. In the Abgesang, or final third of the strophe, the word noch is made to rhyme with itself. Although English and French poets used rime riche as an ornament, German poets considered identical rhyme a serious flaw and scrupulously avoided it. It is unthinkable that a virtuoso like Frauenlob would have committed such a fault—and moreover, both counterstrophes ascribed to Regenbogen display the same flaw, as if pointedly mocking it. If read closely, the boast reveals other signs of parody as well. The “cauldron of art” sounds like a travesty of Frauenlob’s crucible image in the lament for Konrad, and the metaphor of the broad highway in fact reverses a familiar trope in which the most artful poets take the narrow paths, while it is hacks who follow the broad road. Similarly, “gilded” (vergoltem) is an equivocal term that can also mean “counterfeit.”

It appears, then, that the notorious boast was not Frauenlob’s own but the work of a wickedly skillful parodist who wrote it—and perhaps also the counterstrophes—in order to do lasting harm to his rival’s reputation. This could well have been Regenbogen, whom the Manesse Codex presents both verbally and pictorially as Frauenlob’s archrival. Yet Rettelbach nominates Rumelant, another foe, as the parodist because he was the better poet. Circumstantial evidence also suggests that Frauenlob may have ousted Rumelant from his position as court poet to King Erik VIII of Denmark, providing a likely motive for revenge. The conjecture cannot be proven, but the whole incident nicely illustrates the intense rivalry of the Spruchdichter and the competitive atmosphere surrounding court patronage, as well as Frauenlob’s widely recognized ambitions and the distinctiveness of his style. It is a striking fact that, for all the frequency of polemic and ritual aggression among these traveling poets, Frauenlob alone inspired stylistic parodies.

<one line space>

Enemies notwithstanding, the singer’s list of illustrious patrons (including Erik VIII) testifies to the wide esteem he enjoyed. At least two of these patrons were themselves poets—King Wenceslas II of Bohemia and Prince Wizlav of Rügen, who both composed love songs in accord with the time-honored tradition of the noble amateur. It is interesting that language differences do not seem to have hindered Frauenlob’s reception. His native dialect was a form of Middle German, but he spent much of his career in the Low German–speaking regions of the north: Lower Saxony, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg, even Denmark and the Baltic island of Rügen. The last datable event that he mentions is a chivalric feast in the Hanseatic port city of Rostock in 1311. Shortly afterward, however, he settled permanently in Mainz, a High German–speaking city in the Rhineland. His patron there was the powerful archbishop Peter von Aspelt, who may have met the poet in the Bohemian court as early as the 1280s. A high-ranking political figure, Peter had been physician and chaplain to Rudolf of Habsburg (1286), then protonotary to King Wenceslas II (1289), chancellor of Bohemia and bishop of Basel (1296), and finally archbishop of Mainz (1306). It may have been Peter’s patronage that gave Frauenlob the stability to establish a “school,” or at any rate to do some sort of teaching under the auspices of the cathedral, ultimately inspiring the Manesse illustration and the meistersinger tradition. The large corpus of inauthentic poems ascribed to him in the manuscripts might best be explained as the work of his many disciples. At any rate, Frauenlob surely owes his illustrious burial place to Peter’s friendship. Two manuscripts transmit a poignant notice claiming that the poet wrote the first strophe in his Langer Ton (Long Tune) “an sinem leczsten end in der stunde, als im der erczbischoff ze Mencz gotz lichnam mit sinen henden gab” (“at the end of his life, in the hour when the archbishop of Mainz gave him God’s body with his own hands”).

The attentive reader will have noticed that, in the fairly long list of Frauenlob’s patrons, no female names occur, nor do we find any among his fellow poets. This is not Frauenlob’s fault; he did not create the culture in which he sang. But in view of his exalted praise of Woman, a defining mark of his oeuvre, we should not forget that the world of secular German poetry was overwhelmingly male. In striking contrast to medieval France, it offers no counterpart to Eleanor of Aquitaine or Marie de Champagne, no Marie de France or Comtessa de Dia, much less any Christine de Pizan. We do find female-voiced lyrics by male poets, as well as outstanding female religious writers. In fact, all the substantial Latin texts composed by women after 1150 stem from German-speaking lands—a remarkable fact that testifies to the high educational level of nuns and canonesses in the empire, far surpassing the norm for other parts of Europe. Among vernacular sacred writers, Mechthild of Magdeburg (d. 1282) offers some points of comparison with Frauenlob, so we shall return to her. But the poet is not likely to have known her book—or indeed, the work of any female author—unless he encountered some lyrics or other texts by Hildegard of Bingen during his late years at Mainz, where she enjoyed a significant cult. Otherwise, women figure not at all among Frauenlob’s patrons, his fellow Spruchdichter, or his literary influences. More surprising, perhaps, is that this great apostle of Woman’s praise shows no sign of reverence for any private muse: his few Minnelieder reveal no engagement with any flesh-and-blood woman, let alone a Beatrice. The poetic speaker in his debate poem, Minne und Welt, does give thanks for his beautiful wife, but he does so to set an argument in motion; there is no reason to take his statement as autobiographical. Though Frauenlob may well have been married, we know nothing whatsoever of his wife or possible children.

Pace Hermann Damen, then, the “praise of ladies” by which Frauenlob chose to define his poetic self had very little to do with courtly love, and even less with female conversation partners in the world. Rather, all his women are goddesses: Natura, Minne, Sapientia, and above all, the double-natured Lady of the Marienleich, the divine-human Mary, partner of the Trinity, who incarnates both God and the Eternal Feminine. It is such figures as these that we will encounter as we explore the poet’s oeuvre.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.