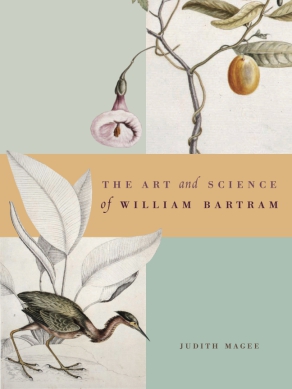

The Art and Science of William Bartram

Judith Magee

“This well-written, accessible, and scholarly book does a splendid job situating William Bartram in the larger context of the Enlightenment, Romanticism, and the rhetoric of European and American natural history.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Winner of a 2008 AAUP Book Jacket and Journal Show for Trade Illustrated

The Art and Science of William Bartram brings together, for the first time, all sixty-eight drawings by Bartram held at the Natural History Museum, along with works by some of the most well-known natural history artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The volume explores Bartram's writings and artwork and reveals how influential he was in American science of the period. Bartram was an inspiration to a whole generation of young scientists and field naturalists. He was an authority on the birds of North America and on the lifestyle, culture, and language of the indigenous people of the regions through which he traveled. His work influenced Wordsworth, Coleridge, and other writers and poets throughout the past two hundred years, and his drawings reveal an ecological understanding of nature that only truly developed in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

“This well-written, accessible, and scholarly book does a splendid job situating William Bartram in the larger context of the Enlightenment, Romanticism, and the rhetoric of European and American natural history.”

“More slithering lowlife can be found in Judith Magee’s luminous The Art and Science of William Bartram. Long before Audubon, Bartram wandered through Cherokee outposts and Florida river basins, circa 1776, filling his notebooks with quasi-surrealist renderings of bobolinks and frolicking alligators. Bartram’s pictures are beautifully reproduced in Magee’s volume, and she makes a good case for his scientific expertise. It’s easy to see why Bartram’s idiosyncratic work stoked the feverish fantasies of Coleridge and Wordsworth.”

“Particularly valuable is the publication, in color, for the first time of all 68 drawings by Bartram held by the Natural History Museum in London as well as natural history illustrations made by Bartram’s contemporaries.”

“Using the best sources and nicely placing Bartram in the context of contemporary scientific thought, Magee provides keen insights into Bartram’s life and contributions. Her work advances our understanding of the role of this important figure in the maturation of natural history studies in America and makes clear the continuing significance of his writings and drawings.”

“Judith Magee, in her handsome book, The Art and Science of William Bartram, gives a delightful overview of Bartram and his contributions to the natural history of his time, especially in his pioneering drawings and watercolors, in which he portrayed behavior, habitat, and the relationships among individual species.”

Judith Magee is Collections Development Manager in the Library of the Natural History Museum, London. She has acted as picture researcher for several publications and has contributed to Plant Discoveries: A Botanist's Voyage Through Plant Exploration (2003) and Great Naturalists (forthcoming).

Contents

Acknowledgments

Chronology

Prologue: Explorer, Naturalist, and Artist

Part I: Formation

1. Plant Hunting and the Seed Trade

2. The Merchant’s Apprentice

3. Cape Fear and Competition

Part II: Experience

4. Travels in Florida with the King’s Botanist

5. Finding a Patron

Part III: Independence

6. Travels: Revisiting Old Haunts and Discovering New Ones

7. Encounters and Observations

8. The Arcadian Dream

9. Describing, Classifying, and Naming

Part IV: Influence

10. American Science Comes of Age: Ornithology

11. American Science Comes of Age: Entomology

12. Following in Bartram’s Footsteps

Epilogue: Contentment and Serenity

List of Drawings

Glossary of Names

Bibliography

Index

Chapter 1:

Plant Hunting and the Seed Trade

All Nature is but Art Unknown to Thee

—Alexander Pope, “Essay on Man,” Epistle 1

On 9 April 1739, William and his twin sister, Elizabeth, were born to Ann and John Bartram. Both children survived to adulthood, as did seven of their brothers and sisters. Ann Mendenhall, William’s mother, was a strong, healthy woman who bore nine children and raised and cared for them while working alongside her husband in farming the land. She lived into old age and died in the house that she and John moved to when they married in 1729. Ann was the second wife of John Bartram and their marriage took place two years after the death of John’s first wife, Mary Maris, and their eldest son, Richard, three years old. Mary’s second son, Isaac, survived and lived with his father and Ann and in later life became an apothecary, working in Philadelphia. The house and farm that John brought Ann to on their marriage was situated at Kingsessing on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, some four miles southwest of Philadelphia. John had substantially enlarged the house himself using stone that he hewed from local bedrock. The house still exists today, kept by the John Bartram Association as a museum and botanical garden. To visit the house, one can take a trolley from City Hall in Philadelphia, which takes the visitor through the sprawling suburbs southwest of the city.

The grounds of the Bartram house are nestled between the Schuylkill River, which flows past the far end of the garden, and municipal housing of red brick and weatherboard houses that stretches block upon block along the busy main road. These houses are not visible from the house or garden, which allows the visitor to capture a glimpse of what life was like in the eighteenth century. The large, well-proportioned stone house overlooks a rambling garden that rolls gently down to the river. Herbs, shrubs, and trees abound, including the oldest Gingko tree in the country and the famous Franklinia that John and William discovered in 1765. The various sections of the garden are full of native plants that the Bartrams grew and listed in their 1783 Catalogue of American Trees, Shrubs and Herbacious Plants. It was in this house that Ann and John lived out their lives, farming the adjacent land and raising and educating their large family.

The Bartrams were members of the Religious Society of Friends and lived within a large Quaker community that had settled in Pennsylvania in the late seventeenth century. Pennsylvania was born out of religious dissent. Its founder and proprietor, William Penn, had secured the land west of the Delaware River in 1681 as payment of a debt owed to his father by King Charles II. William named the land in memory of his late father. Like the Bartrams, Penn was also a member of the Society of Friends, a nonconformist group that questioned the established beliefs of the age. As a result, they were severely persecuted in England, where punitive laws existed that prevented them from worshiping in chartered towns and excluded them from holding public office, teaching, and attending university. William Penn had spent almost nine months imprisoned in the Tower of London for his beliefs and recognized that his newly acquired land could be a refuge for the persecuted members of his religious sect, a land where religious freedom would prevail. In 1682 the first of many ships set sail from England bound for the New World and the colony that Penn described as “a holy experiment” that would become “the seed of a nation.” Pennsylvania expanded at a considerable rate and was the fastest-growing colony of the time. The predominant settlers were English Quakers, but there was also a large community of Germans, the so-called Pennsylvania Dutch. The colony prospered rapidly because of several factors: the rich farmland that was cleared by the settlers, the industrious nature of the settlers, and, above all, the success of William Penn in establishing peace with the local Native Americans. In 1683 Penn signed several treaties with the Delaware Indians that to were essentially maintained for fifty years. These fifty years of peace, which no other colony in America experienced, allowed Pennsylvania to establish a city building program, commerce, industry, and farming. Stimulated by economic success, Philadelphia soon became the intellectual and cultural center of North America.

Among those early settlers to Philadelphia were William Bartram’s great grandparents, who had left Derby, England, in 1683 for their new life of farming the land in Darby, Pennsylvania. It was here that William’s father, John, was born in 1699. John inherited land from his grandmother and uncle when they died and in 1728 added to that already substantial landholding by purchasing an additional 112 acres at Kingsessing. It was here that he built his house, farmed his land, and established what was to become the first botanical garden-cum-nursery in America. The garden at one time probably contained a greater variety of plants from around the world than any other on the North American continent, including an array of indigenous plants from the Northeast. It was never landscaped for aesthetic splendor but remained a working garden and nursery, propagating plants for their interest, beauty, and, above all, for the seed trade that John Bartram established. It was from this garden that John supplemented his income by growing plants he collected on expeditions up and down the eastern coast of North America and by processing the seeds to send to Europe. During his long life, John Bartram built up such a successful trade in plants and seeds to Europe that it allowed one of his sons, also named John, to earn his living solely from this trade. John Bartram Jr. had taken an early interest in the seed trade and assisted his father from adolescence, thereby earning praise from his father’s English friend, fellow correspondent and agent Peter Collinson, who described him as “Our [John & Peter’s] right hand man” and proclaimed, “How happy is it to have children of so agreeable a Cast.” It was John Jr. who inherited, on his father’s death, the garden and the seed trade.

John Bartram’s love and care for his family is unquestionable, but he was a formidable father who was ambitious for his children. He passed down to all his children his own interest in nature, particularly plants. His son John took a great interest in the garden and James, the son who inherited the farmland, was an authority on local flora. Two other sons, Isaac and Moses, became apothecaries, their interest lying in the medicinal properties of plants. But it was William, John’s fifth son, a twin, physically rather fragile, artistically talented, and exceedingly sensitive, with whom John had a special affinity. It was William who traveled as a boy with his father, collecting plants for the garden and drawing the plants and animals they encountered on their expeditions. In later life it was William who continued to explore the wilderness so loved by his father and who succeeded in reaching the Mississippi River in his travels, something his father had dreamed about but never accomplished. It was William who became the son publicly associated with Bartram’s Garden, where, in later years, visitors from around the world would venture out of their way to pay their respects to the “venerable” old man. It was also William who presented the greatest challenge to his father. He was a son whose own nature and vision of his future were contrary to his father’s. While William revered his father and tried to please him, he rarely did so and found that the only way he could resist his father’s overpowering presence was to retreat rather than confront.

John Bartram was a strong, resolute, and steadfast man who would never truly appreciate the doubts, dilemmas, and internal struggles that at times troubled others. John revealed his anxieties and frustrations with William in some of his letters to Peter Collinson, asking advice on William’s career and relating his own disappointments with his son. Toward the end of John’s life, the relationship between father and son became less fraught. From the few letters that exist between them during those years, John’s seem to have a tone of resignation rather than reconciliation. While William’s liberation came through his travels, by his mid-thirties he at last reveals in his last extant letter to his father a relationship of equal partnership.

John and Ann Bartram were relatively wealthy in terms of land ownership, but they also had a large family to support and were happy to supplement their income through the sale to Europe of John’s five-guinea boxes of seeds of indigenous American plants. Throughout the eighteenth century, European demand for new and unusual plants never abated. In the early years, Europe was entering the golden age of pleasure and landscape gardens. This was the period of the emerging English Enlightenment, with greater religious tolerance and liberal ideals on the progress and unity of humankind and personal freedoms. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 put in place many elements that were fundamental to the English Enlightenment, including the rule of law, Parliament, and greater religious freedom. The 1689 so-called Toleration Act had been passed, which gave greater freedom to those who had been oppressed in earlier decades. However, Unitarianism remained punishable by penal law and Catholics and non-Christians were still denied the right to public worship. Nevertheless, gone were the repressive laws that had forced William Penn and his fellow Quakers to seek refuge across the Atlantic.

Religious toleration reflected other changes taking place in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century England. It was a period of scientific innovation with Newtonian science of experimentation replacing that of mere observation. This in turn encouraged inquiry into religious and theological traditional beliefs and reason began to replace revelation and dogma. The ideas expressed by John Locke, the man seen as the father of the English Enlightenment, who championed the natural freedom of mankind, were being espoused by Deists such as Matthew Tindal, whose Christianity as Old as the Creation, published in 1730, was considered the Deists’ bible. Tindal argued that God had given mankind the means, through rationality, of knowing whatever he required of them. Tindal’s beliefs were based on the Creation and universal reason. He argued that “God’s will is so clearly and fully manifested in the Book of Nature, that he who runs may read it.” The eighteenth-century Deists tended to be anticlerical and believed in one true God who was revealed by the light of Reason and not through written text or an intermediary priest. John Bartram’s own religious belief was not much removed from Locke’s and Tindal’s. Like Locke, Bartram read the Bible and accepted that there was a place for revealed truth by applying reason. Reason explained the scriptures and validated the existence of God. And like Tindal, Bartram was a Unitarian who rejected the Trinity and the divinity of Christ.

Hand in hand with greater liberalism in law and religious toleration in England came material wealth for a certain sector of the country’s citizens. In the first half of the eighteenth century, the British economy was affected by several factors. An increase in agricultural productivity and growth in manufacturing and mineral technologies moved Britain and its economy toward industrialization. A rapid growth in the population of the American colonies that was dependent on the more advanced industrial processes of the home country gave the British export market a considerable boost. Adding stimulus to these factors was the expanding Empire and the British dominance of the slave trade. Thus, for some there was a visible rise in disposable income. This wealth provided the opportunity for many to explore science and the natural world and man’s place within it. Some expressed their interest by collecting natural objects such as fossils, rocks and minerals, insects, birds, animals, and plants. The desire to possess ornamental and curious plants from around the world was insatiable. The great expeditions that opened up to Europe new worlds of exotic flora and fauna came later in the century with Captain Cook’s voyages, but in the 1730s, for many in Europe, the American colonies were the main source for new plants.

The passion for interesting and unknown plants was not wholly new to Europeans. Hysteria had gripped Western Europe in the seventeenth century with what became known as “Tulipomania,” when many a wealthy family was brought to economic ruin through the speculation of all they possessed on a handful of tulip bulbs. The mania reached its peak between 1633 and 1637 with examples of traders paying as much as twenty times for a single bulb as what an average family could live on for a single year.

Such mania for plants was replaced in the eighteenth century by a calmer, more rational attempt at re-creating miniature plant habitats of distant lands, particularly American, and the use of plants in sculpting scenes modeled on the landscape paintings of artists such as Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. Alexander Pope, one of the first to apply painting techniques to gardening, wrote the Reverend Joseph Spence in 1734 that “All gardening is landscape painting.” The renaissance of the classical with Palladian architecture was transposed to garden design. Nature was now made to imitate art. Not only were royalty and nobility creating grand and majestic gardens, but so too were the wealthy commoners of Europe. As John Loudon explained in 1838, the Enclosure Acts in England soon changed the face of the country, which then “bore a closer resemblance to country seats laid out in the geometrical style; and, for this reason, an attempt to imitate the irregularity of nature in laying out pleasure grounds was made in England.” New methods of growing plants in heated glass houses enabled enthusiasts, gardeners, and nurserymen to enjoy plants never before seen in Europe. More than 320 plants were introduced from America between 1736 and 1776 (after which trade was disrupted by the revolutionary war) and almost half of these plants were from John Bartram.

The introduction of North American plants into Europe had begun in the sixteenth century with the arrival of corn and tobacco. By the seventeenth century, Parisian gardeners were growing plants from Canada, while English gardens contained plants from Virginia. In addition, botanical literature, such as John Parkinson’s books Paradisus (1629) and Theatrum Botanicum (1640) and Jacques Cornut’s Canadensium Plantarum (1635), recorded North American plants. Many of the plants were introduced because they had an economic or medicinal value and only toward the end of the seventeenth century were plants sought for purely ornamental purposes. These plants were recorded in the works of Leonard Plukenett, Robert Morison, and Paul Herman and were collected by travelers sent to America by wealthy patrons. John Tradescant the younger made three visits to Virginia and John Banister traveled in Virginia and sent a large collection of specimens and seeds to Bishop Compton of Lambeth. Other major recipients of specimens were James Petiver, a London apothecary, and Sir Hans Sloane, an Irish physician and founder of the British Museum, who himself had collected a large quantity of plants from Jamaica while employed as the surgeon to the Governor of the Island.

Both Petiver and Sloane were Fellows of the Royal Society and both had a list of correspondents who sent specimens of plants, insects, minerals, shells, and fossils from the colonies. One of Petiver’s main correspondents was John Lawson, who traveled through the Carolinas and wrote an account of the flora and fauna of the region, A New Voyage to Carolina, in 1709. A much more impressive work was that of Mark Catesby, who embarked on two excursions across the Atlantic, traveling through the Carolinas and the Caribbean in 1712–19 and again in 1722–26. He sent plants back to England for several years and from these collections and his sketches made during his visits he produced the first illustrated natural history book of North America, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1731–43). Many of the plant collectors who visited the American colonies remained there for short periods of time, while the contributions of residents paled in comparison to those of John Bartram.

John Bartram had been interested in plants from a young age: “I have had ever since I was 12 years of age A great inclination to botany & natural history.” He used his knowledge of medicinal plants to treat his family and neighbors. As a Quaker, John Bartram’s interest in plants and medicine was not unusual. The Society of Friends had been founded in 1651 by George Fox and James Naylor and was one of the few sects that survived the Cromwellian years of the Protectorate and the persecution that followed after the Restoration. The Test Act of 1673 politically disqualified Dissenters, excluded them from a range of professions, and barred them from obtaining a university education in England. This prompted the Quakers to establish their own schools, where they encouraged the study of natural history. George Fox had insisted that “the nature of herbs, roots, plants and trees” be taught in the schools. It was with this knowledge of plants that many Quakers were attracted to the medical profession, becoming apothecaries or attending universities in Europe or Scotland and becoming doctors.

John Bartram’s botanical knowledge was mostly self-taught since he had received only a limited formal education from the local Quaker school. He became a farmer as a young man and his doctoring and use of medicinal plants were of a practical rather than a theoretical nature. Many of the local plants in his garden in its early years were used for treating ailments. By the 1730s, Bartram had an extensive knowledge of local flora of all kinds. It was this knowledge that led him to begin a botanical correspondence with an Englishman and fellow Quaker, Peter Collinson.

Peter Collinson, born in London in 1694, was five years older than John Bartram. He too was born into a Quaker family, which originally hailed from the Lake District in Cumbria. With his brother he inherited his father’s wholesale woollen business in Gracechurch Street, London. Much of their trade was with the American colonies and this enabled Collinson to develop a large circle of correspondents in the country. Collinson’s extensive knowledge of science was rewarded in 1728 with his election to the Royal Society, but his main passion was his love of plants and gardening. His gardens, first at Peckham, then later at Mill Hill, were among the finest in London, ranking alongside the garden of his very good friend and fellow Quaker John Fothergill in Essex, and was visited by botanical artists such as Georg Ehret and William King. Collinson corresponded with botanists and plant collectors from all over the world, including Jesuit priests in China and Dr. Mounsey, physician to the Tsarina of Russia. In his Memorandum, written two years before his death in 1768, Collinson recalled how in the early 1730s he had been searching for a reliable source in the American colonies who would send him seeds of new plants on a regular basis: “I labour’d in vain, or to little purpose; for some years.” Eventually in 1733, Joseph Breintnall, a Quaker merchant whose main occupation was as a copier of deeds and who worked in Benjamin Franklin’s stationers’ shop, suggested John Bartram as his man. Again in his Memorandum, Collinson wrote, “Accordingly John Bartram was recommended, as a very proper Person for that purpose, being a native of Pensylvania, with a numerous Family—the profits ariseing from Gathering Seeds would Enable Him to support It.” Thus in 1733 a correspondence began that would continue over thirty-four years between these two men, who never met in person as neither man ever left his native country, but who became intimate friends and comrades through their love of plants.

Both men were great letter writers and we are fortunate that much of their correspondence has been preserved. Collinson’s circle included the leading men of science and politics of the day and he introduced many of these men to John Bartram. Within several years of their first letter, John Bartram was supplying his “five-guinea box” of seeds to a long list of customers in England. Each box contained seeds of 100 to 105 different plants, mainly woody shrubs and trees. The customers who repeatedly came back for more included some of the most notable aristocrats, nurserymen, and scientists of the day. The Prince of Wales purchased boxes for several years in succession. Noblemen such as Lord Bute, who directed the planting at Kew Gardens, the Dukes of Bedford, Argyll, and Richmond, the Earl of Essex, Sir James Dashwood, and General Napier were some whose splendid gardens were rich in American productions sent by John Bartram. Nurserymen such as James Gordon, one of the most highly regarded and influential professionals in the seed trade in the mid-century gardeners such as the Reverend William Hanbury and Philip Miller of Chelsea Physic Garden relied on Bartram for American seeds. Customers in France, Ireland, and Germany also ordered Bartram’s seeds Among the scientists who parted with five guineas were Humphrey Sibthorp and Sir Hans Sloane. The trade was so extensive that it helped shape the appearance of English landscape gardens.

Lord Petre was one of the first Englishmen to be introduced to John Bartram and during his short life was one of Bartram’s major patrons, helping to finance an “annual allowance to Encourage & Enable” Bartram to “prosecute further discoveries.” Lord Petre, with the help of his then gardener, James Gordon, created one of the most magnificent gardens of the time at Thorndon Hall in Essex. In one of his letters, Collinson, who was awaiting new discoveries from America, reveals the scale of Bartram’s success: “The Trees & shrubbs raised from thy first seeds is grown to great maturity Last year Ld petre planted out about Tenn thousand Americans wch being att the Same Time mixed with about Twenty Thousand Europeans, & some Asians make a very beautifull appearance . . . when I walk amongst them, One cannot well help thinking He is in North American thickets.”

In order to “prosecute further discoveries,” Bartram made regular trips along the length of the eastern coast of North America between the harvesting and sowing on his own farm. He became one of the most traveled men in America, covering thousands of miles from Lake Ontario in the north to Florida in the south and west to the Ohio River. He met in person many of those with whom he was already corresponding, men such as John Byrd, who owned a large and splendid garden in Virginia and was one of the few American members of the Royal Society of London. Among others were Alexander Garden, a Scottish doctor who had settled in South Carolina and had a medical practice in Charleston that kept him “from his desire to botanise”; James Logan, secretary to William Penn in Philadelphia, who was reputed to have the best library in America, and who helped Bartram with his Latin and introduced him to Linnaeus; and by no means least, Benjamin Franklin, with whom Bartram remained a lifelong friend and who together founded the American Philosophical Society in 1743. A friend whom Bartram visited several times on his plant-collecting trips was Cadwallader Colden of New York, one of the most articulate and knowledgeable men of science in the colonies, and with whom Bartram corresponded for many years, exchanged plants and seeds, and maintained a dialogue on botany and natural history.

Colden was born in Ireland of Scottish parents, who then returned to Berwickshire, Scotland, where Cadwallader was raised and educated. In early life he intended to follow his father’s profession as a Presbyterian minister, but while at Edinburgh University he became interested in the sciences and in 1705 went to London to study medicine. He completed his studies in 1708 and decided to practice as a physician in the colonies. In 1710 he set sail for Pennsylvania and settled in Philadelphia. He returned to Scotland several times, and on one of these visits, in 1715, he married Alice Christy, the daughter of a Scottish minister, and the two returned to America the following year.

Cadwallader Colden did not practice as physician for very long in America, for he soon became the surveyor general for New York, a post that allowed him to be involved in land speculation and become relatively wealthy. He purchased three thousand acres of land north of New York City in the Hudson River Valley, now the town of Montgomery in Orange County. Here he built a grand house and named his estate Coldengham, where the family settled permanently in 1728. The Coldens had ten children, whom they educated at home. Colden’s son, Cadwallader Jr., wrote that his mother, Alice, conducted much of the children’s early education and that all of them were encouraged to develop their own intellectual pursuits.

Colden was himself part of the international network of scientific correspondents that included Linnaeus, Gronovious, Collinson, Franklin, and John Bartram. His interests were far-ranging and he had a broad knowledge of science. His study of history and ethnography led him to write a History of the Five Indian Nations Depending upon New York (1727). He became a serious botanist after reading Linnaeus’s Plantarum Naturae and was one of the first to apply Linneaus’s classification system to plants in America. He wrote a local flora of New York entitled Plantae Coldinghamiae, which was published by Linnaeus in 1749. This was the first attempt at the systematic classification of American plants. In later life Colden diverted his energies toward his interest in physics, writing An Explication of the First Causes of Action in Matter, in which he attempted to explain Newton’s theory of gravity. Colden was one of the few Americans to observe the transit of Venus across the face of the Sun in 1768. He also took an interest in politics and became a member of the Council of New York and later, in 1761–76, served as lieutenant governor of New York.

In 1753 John Bartram visited the Colden estate as part of his excursion to the Catskill Mountains. He wrote to Collinson before he left, “I am preparing for A Journey to dr. Coldens & ye mountains I desighn to set out with my little botanist ye first of September.” The “little botanist” was his son William, then fourteen. William was as young as twelve when he started to accompany his father on his trips. “I have A little Son about fifteen years of age that has traveled with me now three years & readily knows most of ye plants that grows in our four governments.” Through John’s friendship, William had already been introduced to Peter Collinson and had presented him with some of his drawings of plants and birds. Both Collinson and George Edwards, the author of A Natural History of Birds (1743), were recipients of William’s early drawings, and Edwards used the drawings for his engravings in his books, while Collinson showed them to scientists and artists of natural history. “There is a Little Token to my pretty artist Billey His Drawings has been much admir’d,” wrote Collinson in appreciation.

The expedition of 1753 resulted in the Bartram’s spending three days at Coldengham, where they met with Colden’s second daughter, Jane, who had developed a keen interest in botany. Jane was born in 1724 and according to her father exhibited intellectual prowess at an early age and also possessed “a curiosity for natural philosophy or natural history.” Colden took particular interest in his daughter’s education and provided an extensive library of botanical literature. He explained to a friend that Jane did not read Latin and so Colden “took the pains to explain Linnaeus’s System, and to put it in English form for her use by freeing it from the technical terms.” The translation of Genera Plantarum enabled her to master Linnaeus’s classification system and apply it to her own work.

Jane Colden became well known in botanical circles in both America and Europe and was without doubt highly respected by those who met her or knew of her work. Peter Collinson wrote to John Bartram about their “Friend Coldens Daughter,” explaining that Jane had sent him some sheets of plants with scientific descriptions that she had done according to the Linnaean method: “I believe she is the first Lady that has Attempted any thing of this Nature.” The following year, in one of his letters to Colden, Collinson enclosed “2 Vol. of Edinburgh Essays for the sake of the Curious Botanic Dissertation of your Ingenious Daughter. Being the Only Lady that I have yett heard off that is a professor [of] the Linnaean system of which He is not a Little proud.”

Alexander Garden was a friend and correspondent of Colden and was himself an amateur plant collector and botanist. In 1755 he wrote to John Ellis of London about Colden and his daughter: “Not only the doctor himself is a great botanist, but his lovely daughter is greatly master of the Linnean method and cultivates it with great assiduity.” Jane Colden is now recognized as the first American woman botanist and several attempts were made during her lifetime to have a plant named after her, both Collinson and John Ellis suggested this to Linneaus. Collinson presented his request in 1756; “I but lately heard from Mr Colden. He is well; but, what is marvelous, his Daughter is perhaps the First Lady that has so perfectly studied your system. She deserves to be celebrated.” John Ellis went a step further in 1758, when he sent one of Jane’s plant descriptions that he had translated into Latin to Linnaeus: “This young lady merits your esteem, and does honour to your system. She has drawn and described 400 plants in your method only. . . . Her father has a plant called after him Coldenia, suppose you should call this Coldenella or any other name that might distinguish her among your Genera.” However, Linnaeus may well have been a little proud and flattered by Jane’s work, but none of the above pleas was successful and no plant exists today that honors Jane Colden’s name.

Few of Jane Colden’s writings have survived. Her main work is the manuscript held in the Natural History Museum in London, of the flora of New York, Flora Nov-Eboracensis. The volume consists of 284 sheets of line drawings of leaves and scientific description of each plant. The descriptions, written in English with Latin names and the common name where known, are considered to be excellent. For some plants she has added their medicinal and folk use, explaining who used the plant and for what ailments, and even included the prescribed dosage and method of application. “This S’eneca Snake Root is much used by some Physicians in America, principally Long Island, in the Pleurisy, especially when it inclines to a Perip neumony, they give it either in Powder or a Decoction. The usual Dose of the powder is thirty grains.”

Jane Colden’s drawings are, as James Britten notes, “very poor, and consist only of leaves. The figures are merely ink outlines washed in with neutral tint.” The last image in the collection is a nature print. These drawings probably do not give justice to how skilled an artist Jane Colden was. According to several letters, she is described as an accomplished draftswoman. Her father describes to Johann Gronovius that “She was shown a method of taking the impression of the leaves on paper with printer’s ink, by a simple kind of rolling press. . . . No description in words alone can give so clear an idea, as when assisted with a picture.” Nature printing was a fashionable pastime for many and Joseph Breintnall, the man who introduced Bartram to Collinson, produced many such illustrations, and indeed relied on John Bartram to find specimens and identify them for him. A letter by Walter Rutherford reports of a visit to the Colden estate, “the abode of the venerable Philosopher.” Here Rutherford describes Jane as “a botanist, she has discovered a great number of Plants never before described . . . and she draws and colors them with great beauty.”

When William visited the Coldens for the first time in 1753, he and his father spent time looking over some of Jane’s “botanical curious observations,” which no doubt would have included her drawings and nature prints. William Bartram may well have considered Jane Colden a respectable artist judging from the reply John Bartram gives to one of her letters, which he received on 26 October 1756, and had read “several times” to his great satisfaction: “I should be extreamly glad to see thee at my house & to shew thee my garden. . . . I shewed him [William] thy letter & he was so well pleased with it that he presently made a pockit of very fine drawings for the far beyond Catesbys took them to town & tould me he would send them very soon.” The keenness of William to send Jane some of his drawings hints that he had been impressed with Jane’s attempts at illustration and that it was their equal love of drawing that was the key to the cultivation of such an affectionate friendship between Jane and the Bartrams. It is not known whether Jane ever made the trip to Philadelphia to visit the Bartram garden. By 1759 she had married Dr. William Farquhar, a widower practicing medicine in New York City, and there is nothing to suggest that she continued her botanical investigations after her marriage. Tragically Jane died in 1766, soon after giving birth to her only child, who did not survive.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.