The Passion Story

From Visual Representation to Social Drama

Edited by Marcia Kupfer

“Marcia Kupfer has assembled an impressive group of world-class scholars, writing across the spectrum of media, periods, and methodologies. This very readable collection of essays offers a rich investigation of a perpetually timely topic. The essays on film, in particular, break new ground.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Contributors include Robin Blaetz, Stephen Campbell, Jody Enders, Christopher Fuller, James Marrow, Walter Melion, David Morgan, David Nirenberg, Adele Reinhartz, Miri Rubin, Lisa Saltzman, and Marc Saperstein.

“Marcia Kupfer has assembled an impressive group of world-class scholars, writing across the spectrum of media, periods, and methodologies. This very readable collection of essays offers a rich investigation of a perpetually timely topic. The essays on film, in particular, break new ground.”

“After reading this powerful collection of essays that so admirably capture one side of the Passion narrative—its images and resulting horror—the reviewer can only hope for a future collection generated by this one that seeks to explore the positive spirituality generated by the Passion and its depiction.”

Marcia Kupfer is an independent scholar. She is the author of The Art of Healing: Painting for the Sick and the Sinner in a Medieval Town (Penn State, 2003) and Romanesque Wall Painting in Central France: The Politics of Narrative (1993).

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Marcia Kupfer

Part One: Narrative Transformations, Pictorial Elaborations

1. Inventing the Passion in the Late Middle Ages

James H. Marrow

2. The Passion of Mary: The Virgin and the Jews in Medieval Culture

Miri Rubin

3. The Conflicted Representation of Judaism in Italian Renaissance Images of Christ’s Life and Passion

Stephen J. Campbell

4. Ex libera meditatione: Visualizing the Sacrificial Christ in Jerónimo Nadal’s Annotations and Meditations on the Gospels

Walter S. Melion

Part Two: Popular Spectacle, Mass Consumption

5. Coups de Théâtre and the Passion for Vengeance

Jody Enders

6. Images of the Passion and the History of Protestant Visual Piety in America

David Morgan

7. Realizing the Passion on Screen

Robin Blaetz

8. Jesus of Hollywood

Adele Reinhartz

9. Two Thousand Years of Storytelling About Jesus: How Faithful Is Pasolini’s Gospel to Matthew’s Gospel?

Christopher Fuller

Part Three: Jewish Perspectives

10. Jewish Responses to the Passion Narratives

Marc Saperstein

11. Barnett Newman’s Passion

Lisa Saltzman

Epilogue: A Brief History of Jewish Enmity

David Nirenberg

Notes

Index

Introduction

Marcia Kupfer

How to understand the state-imposed execution of Jesus, a Galilean Jew, on a Roman cross nearly two millennia ago? The religion constituted around the first-century rabbi from Nazareth contemplates his death in light of his identification as “the Christ,” the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew word meshiach (messiah), literally meaning “anointed.” The ancient term is redolent both with royal connotations implying descent from the biblical king David and with apocalyptic promises ushering in Israel’s restoration at the end-time. An inflected form of the Greek epithet christos also designated early followers of the Jesus movement. Christ became a second proper name for their savior figure, signifying to them his filial relation to God and, ultimately, his participation in the Godhead.

Christianity places the Crucifixion at the center of a theology of salvation. God, having assumed a mortal body in the person of Jesus, endured abuse, scorn, and a spectacular slaying in order to redeem, or ransom, a fallen humanity. This divine act of restitution compensates a primary rupture in the cosmic order. Adam and Eve, when they disobeyed God’s command not to eat from the tree of knowledge, committed the original sin; the first parents’ rebellion against God brought about the loss of earthly paradise, thereby condemning future generations to physical hardship, pain, and death, consequences of spiritual separation from the Creator. Repayment of the sin-debt and the return of humanity to its initial status in the divine plan necessitated a sacrifice so great that only God incarnate could perform it. The word “passion”—from the Latin noun passio, an intense suffering or forbearance—sums up the martyrdom to which Jesus assented and which later Christian saints relived when they accepted martyrdom in his name.

Whereas faith alone asks and answers the question, to what end Christ’s Passion? the associated images, ideas, and emotions that the phrase now calls forth properly belong to the realm of historical inquiry. Between the death of Jesus as he experienced it and the transcendent significance that the faithful invest in it come layers of mediation: the translation of events into text well after the fact (beginning in the last quarter of the first century); the selection of specific accounts to be enshrined within a canon of sacred, New Testament writings (between the late second and mid-fourth centuries); the formation of conventions of scriptural interpretation that, from late antiquity, served as the bedrock of Christian learning; the codification of orthodox dogma bearing on Christ’s dual nature, at once fully human and fully divine, and the Virgin Mary as mother of God (decreed at church councils between 325 and 451); the parallel elaboration of apocryphal biography; ongoing theological speculation and doctrinal refinement; the evolution of liturgies for the public commemoration of Christ’s sacrifice daily in the Mass and annually during Holy Week, and of modes of private devotion; the development of an ecclesiastical apparatus responsible for the propagation of, and adherence to, the tenets of the faith; and, not least, the periodic efflorescence of movements of church reform. All these complex dynamic processes have informed the portrayal of Christ’s Passion in the pictorial arts, literature, theater, and film. Critically, artistic traditions have in turn shaped beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

Indeed, no narrative from the entire Christian repertory better demonstrates the powerful impact of relentless representation. Any attempt at retelling or mentally recalling the sequential events of the Passion story—Jesus’ agonistic prayer, arrest, interrogation, scourging, mocking, and crucifixion—today elicits more or less fixed scenarios. Set imagery intervenes, overwhelming the terse passages in the four Gospels that recount his final day in Jerusalem. Although visual and literary depiction has always claimed the prior authority of Scripture, amplified description and direct emotional address displace even as they vivify the originary Word. When it comes to the Passion, not only is artistic representation impossible to circumvent; it is the primary vehicle through which the faithful imagine, absorb, and gain understanding of Christ’s death. The Passion story, moreover, is of paramount concern beyond its religious meaning to believers, for it is also the prism through which Christianity has historically fashioned and purveyed representations of Jews and Judaism.

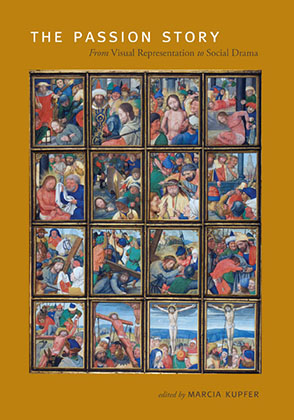

A small altarpiece, now in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, exemplifies the iconographic construct that has come to epitomize the Passion. The work, painted ca. 1525 by the Flemish illuminator Simon Bening, comprises sixty-four vellum miniatures set in rows across four panels. The sequence of twenty-four scenes chronicling Christ’s Passion is so closely paced, the compositions so tightly interwoven, that serial action unfolds nonstop in virtually protocinematic fashion (plates i and ii). An extended Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, drawn out over four haunting “frames,” allows us first to watch Jesus from behind as he kneels in prayer and prostrates himself; then the view cuts around so that we see up close his sweating visage. With the traitor’s kiss comes the garish light of flaming torches and helmeted soldiers brandishing fearsome pikes. Bound with ropes, the captive is hauled before the high priests, his hair yanked, his head covered with a towel, his person assaulted by jeering men. On he goes to Pilate and Herod; along the way, he is dragged through a mucky brook, while soldiers cross over on a bridge (the scene is currently out of sequence, misplaced during the work’s original assembly or a later renovation). Gratuitous beatings, however, are merely a precursor to a Flagellation sequence that leaves him a bloody pulp; the salvific liquid soaks the pavement (plate iii). Plaited thorns, applied with maximum pressure, gouge his forehead. Yet such punishment does not appease the crowd, who, on beholding the man, will have nothing but his crucifixion. Frame by frame, we follow the tortuous path to Golgotha, where he is disrobed, his limbs stretched to the breaking point and nailed onto the cross; we see the cross being raised into position, the sponge lifted, the lance thrust into his side.

Bening exploited every pictorial strategy available in his day to foster in viewers the sense of being “right there” witnessing the violence, helpless to intervene. His lingering over the infliction of pain anticipates the approach taken nearly five hundred years later in Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ; the latter, of course, deploys twenty-first-century technology further to erode the gap between audience and representation. Repudiating Hollywood’s customary picture of Jesus, teacher and miracle worker, as personal savior, Gibson conjures instead the Man of Sorrows—pummeled, hurled, and taunted, flayed into a single oozing wound whose profusely flowing blood washes away the sins of the world.

The iconographic tradition on display in the Walters quadriptych had been widely disseminated throughout northern Europe by the sixteenth century. It permeated the consciousness of the German nun Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774–1824), whose purloining of late medieval imagery in the form of dolorous “visions” inspired Gibson’s screenplay. Inextricably bound up with the dolorist legacy inherited by Emmerich and championed by Gibson is another pervasive feature of Passion imagery, namely anti-Semitic caricature. The Jews’ hideous physiognomy (demonstrably traceable to animal metaphors), satanic embodiment, and avarice—all present in Gibson’s film no less than in countless textual and pictorial materials that Emmerich reenvisioned—are age-old markers for an entire people’s intrinsic depravity as well as for the spiritual bankruptcy of their religious practice.

This volume takes up the enduring place of the Passion story in our religiously pluralistic society. Gibson’s Passion of the Christ, released on Ash Wednesday (first day of Lent) 2004, set off a firestorm that engrossed the media, clergy, and scholars. For weeks on end, an outpouring of commentary and editorial worldwide debated the movie’s premises, agenda, cinematic merits, and reception; several collections of essays devoted to analysis of the film and the controversy surrounding it have since been published. Concentrated critical attention on a singular passing phenomenon, however, has left in its wake the need for a different kind of book, one that explains to nonspecialists the formation and ramifications of the artistic heritage behind the screen version. If, in the pages that follow, contributing authors refer to Gibson’s film at all, they do so in the context of arguments illuminating basic aspects of a central preoccupation in Western societies past and present.

When and why did the Passion story coalesce around the image of a brutalized, slaughtered Christ? What kinds of imagery have alternative traditions proposed? Do particular media, notably theater and film, entail specific problems of representation? Clearly, the complementary activities of visualizing and reenacting the Passion have consumed vast resources in all spheres of cultural production. But what social functions have these activities performed? What has intense, sustained, and ubiquitous focus on the Passion in Christian societies meant for Jews? Does the cult of the Passion—the ways in which it has been institutionalized within the various churches, internalized through the discourse of spirituality, and fetishized in popular piety—bear responsibility for violence wreaked upon Jewish communities through the ages? How have Jews reacted to the instrumental role into which the Passion story scripted them? How have Jews interpreted Jesus’ death? Approaching such questions from diverse disciplinary perspectives, the essays collected here look broadly at the history of the Passion story in western European and American culture, the creative energies it compelled, and, yes, the destructive permutations of those energies.

Surprising though it may seem in retrospect, the formalization of the Crucifixion in visual terms took hundreds of years. The fledgling art of the religion endorsed after 312 by the Roman emperor Constantine the Great (r. 306–37) and newly inundated with state resources soon devised compositions to recapitulate selected episodes of the Passion story: Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, the kiss of Judas, Christ’s arrest, Peter’s denial, Christ before Annas and Caiaphas, Christ before Pilate, Pilate washing his hands, Simon of Cyrene bearing the cross, the crowning with thorns, or rather the victor’s laurel wreath (fig. 1). At the same time, however, the earliest Christian art eschewed any depiction of Christ crucified. Rather, a geometric sign, the cross, alluded only indirectly to crucifixion as a method of execution. Variously garlanded with a laurel wreath, combined with a monogram of Greek letters (chi and rho for christos), or flanked by diminutive figures of soldiers referring to the guard posted at the empty tomb, the cross was an abstraction of a military trophy that celebrated and symbolized Christ’s victory over death; in scenes depicting the road to Calvary, Simon carries the cross like a battle standard, as does Peter in some images of Christ handing down to the apostle the scroll of the new Law. The lynchpin in Constantine’s effort to mythologize his consolidation of imperial power, the cross subsequently became, through legends of his vision promising victory over his rival Maxentius and his mother’s pilgrimage to Jerusalem, a major theme in Christian spirituality and art.

Still, images of Christ on the cross did not appear before the second quarter of the fifth century, and even then the figure was depicted emphatically alive, unscathed by the humiliating ordeal of crucifixion (fig. 2). The very admission of the crucified Christ into the pictorial repertory attests the hegemony of orthodox theology, so declared by its proponents, who held that Jesus was both, and equally, God and man; competing formulations, branded heretical, were suppressed. The Crucifixion, overshadowing the denouement of the Passion story in Jesus’ resurrection, was made to do double duty as proof of the incarnate Christ’s unequivocal humanity and his divine defeat of death. The task of explicating Scripture in support of orthodox Christology transformed the symbolic device of the cross into a narrative scene of Calvary that included such elements as the Virgin and the disciples, the thieves, the soldiers casting lots, Stephaton with his sponge, and Longinus with his lance. If, as John Dominic Crossan has famously put it, the Passion narratives within the New Testament canon were themselves the result of “prophecy historicized,” then Christian art went further: iconography based on exegesis became history reified. To be sure, events recounted in the Bible did not merely happen; historia sacra reflected and fulfilled a transcendent purpose. By conflating different moments of the Crucifixion (e.g., Stephaton’s slaking Christ’s thirst and Longinus’s piercing his side, which latter occurred only after his expiration), contradictory corporeal attitudes (e.g., the erect posture of a still vigorous body with an inclined head and wide-open or, more rarely, closed eyes), and allusions to the liturgy (e.g., angels hovering above the cross), early medieval images visually bridged the gap between the mortal, dying, and dead Jesus and the ever-living, victorious God.

Only toward the end of the first millennium did the representation of Christ unambiguously dead on the cross begin to circulate in the Latin West, a key development that accompanied official, ecclesiastical acceptance of cult images (fig. 3). In contrast to the triumphant Crucified, who exuded vitality, the limp, distended corpse sagging under its own weight proposed a meditation on the enormity of the retribution that God exacted for humanity’s sins. The pathos of the dead Christ ca. 1000 demanded expiation worthy of the Crucifixion, supplication that would sway the Divine Judge. Christ’s sacrifice, moreover, was reinstantiated, daily and everywhere, at the altar during the Mass: as the priest uttered the words of consecration, bread and wine miraculously became the real flesh and blood of Christ’s incarnate crucified body. The “realist” conception of the Eucharist, first articulated in the ninth century, guaranteed divine presence. Relics embedded in images or, as in the case of the crucifix reproduced here, so reported by contemporary apologists for the production of such works, accomplished a similar goal. Saints’ bones, slivers from the wood of the true cross (recovered by Constantine’s mother, Helena), and consecrated hosts (eucharistic wafers) imbued images with the sacred, thereby making them legitimate objects of veneration.

In sum, Crucifixion iconography, whether distilled to the lone figure on the cross or enlarged to a multifigure composition, gradually integrated the dead Christ. Yet expanded pictorial description of physical suffering was by no means a foregone conclusion. It required a shift in theological perspective and a radical reschooling of religious emotion. The crusading movement of the late eleventh and twelfth centuries reawakened interest in the holy places of Christ’s earthly life, stimulating heightened awareness of his historical existence. To reflect on Christ’s humanity was to reflect, above all, on the Passion, the reason why, explained Anselm of Canterbury (d. 1109), God had become man in the first place. Anselm’s devotional prayers, no longer petitioning the Crucified in dread but crying out in love, sparked a spiritual revolution. By the thirteenth century, a new affective ideal had emerged that aspired to empathic embrace of the Virgin’s maternal grief and complete ecstatic identification with Christ in pain. Saint Francis of Assisi (d. 1226), whose rapt meditation on a crucifix inaugurated the phenomenon of stigmata, exemplified perfect assimilation to the image of the Crucified.

An emotionally intensified, demonstrative model of piety henceforth gained ever wider currency. Artistic representation responded to and reinforced the desire for an experiential relation to the sorrows of the Passion. Contemplating Christ’s ravaged body (fig. 4), visualizing the actual delivery of insults and wounds, became not only possible but, as a goad to tears, necessary. The prescribed exercise of mentally restaging the Passion moment by moment, all the while projecting the self into imagined scenarios, yielded cathartic fruits: a psychic emptying or cleansing leading to renewal, or, in Christian terms, a puncturing of the heart (compunction) leading to consciousness of sin, repentance, and longing for God. The practice also underscored the cruelty of Christ’s executioners, throwing each vicious assault into high relief. If to see Christ suffer out of divine love for humanity aroused pity, remorse, and love in return, then to see the savagery of his tormenters incited feelings of righteous vengeance, all the stronger for having to compensate the guilt of the helpless spectator. Who were Christ’s wicked antagonists? None other than the Jews, whose rejection of Jesus the New Testament writings attributed to diabolical inspiration, whom the early church fathers charged with deicide, whom preachers routinely demonized, whose continued existence the church permitted only insofar as their subjugation affirmed Christian truth.

Ritual interaction and narrative production centered on the Eucharist concurrently promoted traditional uses of the Passion story to novel effect. The liturgy expressed, kindled, and channeled devotion toward the sacrificial body of Christ, which regularly and carnally materialized in the guise of bread and wine consecrated by the priest. The doctrine of real presence, having prevailed against intermittent challenges, was finally promulgated in 1215. Officiating clergy, however, had already begun performing the Mass so as to maximize the drama of the sacramental action taking place at the altar. At the sacring, the ringing of bells announced the precise moment of Christ’s arrival through transubstantiation; the celebrant elevated the host above his head so that the faithful could behold God and kneel in adoration. Within a hundred years, the feast of Corpus Christi crystallized around the Eucharist’s supernatural powers, and this potency, together with the Eucharist’s truth and glory, often manifested itself through miracles involving Jewish malevolence.

Monstrous crimes imputed to the Jews encoded, by way of displacement and inversion, the Passion story’s most salient motifs. The torment that the Jews had long ago inflicted on Christ they still worked on his eucharistic body and on the Christian body politic. From hosts treacherously acquired they drew holy blood (plate iv). Alternatively, the Jews crucified Christian children and drained their blood, which they consumed. Needless to say, tales of host desecration confirmed the identity of the Eucharist with the crucified Christ, while those of ritual murder confirmed the magical power of Christian blood fortified by communion. But it was not only the lurid fictions that mimicked the Passion. Their very real outcomes—the judicial torture of the accused, the pogroms that subsequently engulfed entire Jewish communities—also reiterated the tearing and piercing of flesh, the pulling apart of limbs, indeed, mock crucifixion itself (fig. 5). Learned clergy, who did not do the killings but enabled and encouraged them, held up the Gospel accounts of Christ’s Passion as the template for the divinely sanctioned extirpation of Jewish communities. Hence, as Miri Rubin has noted in her revealing study of host-desecration accounts, one Latin text, in English The Passion of the Jews, paid tribute to the Holy Week massacre in Prague 1389.

The sequence of sensational criminal accusation, violent redress, and restoration of Christian order typically coincided with the Easter season, although violence during Holy Week did not need the provocation of an extraordinary event. Whether annual assaults on Jewish quarters took the form of barely controlled, staged gestures, such as throwing stones and setting fires, or exploded into murderous rampages, they reiterated Christianity’s foundational narrative. Ritualistic violence at once situated the Jews at the source of traumatic sacrifice and celebrated their defeat by confirming their radical exteriority from the body politic. Thus did the Passion story flow seamlessly between the aesthetic sphere of pictorial art, literature, and theater, which it utterly dominated, and the lived realm of social drama.

The preceding overview, necessarily compressed, lays the groundwork for essays that take the chronological trajectory forward from the Middle Ages to our time. The relationship between historical developments and modes of cultural production further guides the organization of the studies. In each of three sections, wide-ranging investigations (Marrow, Rubin, Campbell, Enders, Morgan, Blaetz, Reinhartz, Saperstein) complement the close reading of single works (Melion, Fuller, Saltzman). As authors consider distinct issues that arise from the diverse materials with which they are engaged, their contributions cumulatively underscore the multidimensionality of the Passion story in its various articulations.

Part One examines the interplay of iconographic, narrative, and theological invention through which the Passion as now commonly conceived was elaborated in the late medieval and early modern periods. James Marrow tracks the transformation of the Passion from skeletal episodes modeled after the economy of narration in the Gospels to the graphic panoply of cruelty that modern observers often mistake for transparent realism. He dissects images of the Bearing of the Cross and the Flagellation to expose the exegetical method responsible for generating what appears to be descriptive reportage—the injuries done to Christ, the grotesque, bestial faces and contorted poses of his enemies. Interestingly enough, the narrative amplification of the Passion between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries parallels the initial composition of the Passion narratives in the late first century. The authors of the Gospels, mining Hebrew Scripture for passages to vindicate the contradiction between crucifixion and messiahship, converted familiar poetic metaphor and ancient sacrificial protocol into specific incidents in their stories of Christ’s death (Crossan’s “prophecy historicized”). Medieval Christians, trained to read the corpus long since christened the Old Testament as pertaining to Jesus, extrapolated from prefiguration after prefiguration the literal details of the events of the Passion. Christ’s body was the primary but not the sole locus for pious reflection on the sufferings of the Passion. Miri Rubin attends to the role given the Virgin in the cult of the Passion (Maria compatiens), scrutinizing the mix of legend and psychological identification that made her “co-suffering” a force for both compassionating others and directing their hatred to Jews.

Stephen Campbell moves the discussion to Renaissance Italy, where the pictorial defacement of Christ’s body never took hold. Instead, classicizing ideals of physical beauty penetrated deeply rooted artistic approaches to the Passion that harked back to Italian adaptations of Byzantine icon painting. The rejection of the mutilated body as appropriate for the depiction of Christ and hence of its narrative corollary, his executioners’ sadism, pushed the pictorial critique of Judaism in other directions. Humanist iconographers devised recondite allegories of the Crucifixion attended by personifications of church and synagogue, a venerable tradition in Christian art (see the early-eleventh-century miniature in Marrow’s essay). A darker manifestation of Judeophobia coincided with the only subject area where Italian Renaissance art did indeed indulge in blood and gore, namely tales of host desecration and ritual murder, surrogates for the Passion. The phantasmagoric construction of Jewish excess in grisly images showing the exsanguination of little Simon of Trent, for whose murder in 1475 the city’s Jews were blamed, migrated into the representation of Christ’s circumcision.

The Protestant Reformation occasioned on both sides of the sectarian divide a reevaluation of the function of representation. Did visual images distract from the word of God, obstruct inward apprehension of and commitment to Christ, or, worse, promote idolatry? The Council of Trent, which convened in 1546 and spent the next seventeen years outlining the institutional, doctrinal, and liturgical program that has come to be called the Counter-Reformation, answered a resounding no. Art in the service of Catholic renewal nevertheless responded to Protestant challenges both defensively, by linking Passion imagery more tightly to the Gospel text, and offensively, by mastering various techniques of persuasion. Sacred personages were simultaneously brought down to earth and made more heroic; so too, elevating the consciousness of the faithful to heavenly realities entailed making sublime mysteries more palpable. At the vanguard of the movement to clarify Catholic positions and revitalize traditional forms of piety stood the Jesuit order founded by Ignatius Loyola.

Walter Melion analyzes the production for the order of an ambitiously illustrated guide to meditation that correlates engraved scenes of Christ’s life with the sequence of Gospel passages excerpted for reading during Sunday and holiday Mass. A system of notational cross-references attaches the private labor of contemplation to the public prayer of the Roman Church. On the basis of selected Passion scenes, Melion explicates a scholastic argument that conceives Christ’s sacrificial body itself as a work of divine artifice and the votary’s spiritual self-transformation as a pictorial endeavor. The profound affinity between the Christian theology of an incarnate God and a concomitant theory of artistic representation is here laid bare.

Part Two considers theater, ephemeral installations, and film, media that translated the Passion from the realm of high art into popular and ultimately commercial venues. Although speculative theology framed the Passion as a love story between God and man, the great masses of the faithful experienced that story in the form of a revenge play. Jody Enders tackles the internal tensions that the theatrical staging of the Passion in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries could not quite paper over. The narrative of cosmic crime and divine punishment, source of cathartic pleasure, competed with, if it did not drown out, attempts to convey the message of forgiveness. The goal of theater, she reminds us, clashes with that of faith: the former aims to make people believe what they see, whereas the essence of the latter is to believe in what cannot be seen. Medieval and early modern opposition to the performance of sacred subjects turned on the illusionism inherent in theater, which both Catholic and Protestant critics attributed to a literalist, carnal impulse that impeded spiritual understanding. They therefore condemned religious drama (as they did each other’s religious practice) for being “Jewish” in nature: the Passion play, however vividly it portrayed the Jew as the enemy of (the) faith, could be contemptuously dismissed as “Judaizing.” This rhetorical maneuver conforms to a broader pattern that David Nirenberg addresses in the epilogue.

With David Morgan’s essay on Protestant use of visual images, we leave Europe for the United States. Rebutting the oft-repeated claim that Protestant culture in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century America dispensed with sacred images, Morgan points to the acceptance of spectacle as a legitimate vehicle through which the devout experienced God’s real presence. Biblical panoramas; exhibitions of contemporary paintings; large-scale models of the Holy Land (not dissimilar to the creation, beginning in the fifteenth century, of Passion parks in urban northern Europe and sacred mountains in rural South Italy); and theatrical performances, photographic compendia, and early films of the Passion play—all served to uplift and inspire as well as to instruct. American Protestants disdained not visual representation per se but rather what they considered an effeminate portrayal of Jesus associated especially with Italian Renaissance painting. Precisely because religion was primarily the responsibility of women to inculcate in children, images had to do the compensatory work of salvaging the savior’s masculinity and, with it, paternal authority.

The intimate relationship between popular religious images and Hollywood movies, which, as Morgan notes, led to their cross-contamination, brings us to cinematic treatments of the Passion. Writing on the failure of almost all Jesus flicks, Robin Blaetz investigates how film deals with the conflict between verisimilitude and belief that Jody Enders discerns with respect to theater. The most intractable problem that filmmakers confront when tackling the Jesus story is the way in which the medium of film works to privilege viewers’ awareness of the actor as opposed to the role. On the one hand, most Jesus films have as their objective an illusory real-time re-creation of a historical world parallel to our own. On the other, the actors’ very corporeality—physical appearance, carriage, speech, not to mention their stardom and association with previous roles—interferes with their impersonation of the protagonists, blocks our willing suspension of disbelief, and sometimes invites ridicule. The recognizably modern body of the actor, by virtue of its larger-than-life on-screen presence, undermines, if not altogether shatters, the reality effect proper to the cinematic enterprise.

Gospel personages are “known” to movie audiences thanks to centuries of religious images. The film actor simply lacks the credibility of the depicted counterpart ingrained in the popular consciousness. Hollywood’s habitual recycling of pictorial conventions in an attempt to bridge the credibility gap, that is, to supply the spiritual aura that the actor lacks, uncannily rehearses a fundamental and quite self-conscious dynamic in the history of Christian art. Sacred images have always derived their legitimacy by referencing other images in a chain of representation authenticated by dreams, visions, and miraculous prototypes not made by human hands. The authority of the likeness is inversely proportional to the degree that ordinary human artifice and embodied faculties are involved in the production of the image (waking visions are superior to dreams; divine imprints supreme). Blaetz reviews strategies that filmmakers, including Gibson, have deployed to preserve the integrity of their representation of Jesus from disruption by the actor’s body. One is worth mentioning here. George Stevens’s Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) inserted Max von Sydow, who plays Jesus, into the iconic chain by opening and closing with a shot of a church dome in which the painted image of Christ bears the actor’s face. The actor is thereby retrojected into the history of art, which verifies his fictive identity as the real person who preceded and inspired that history. Of course, no viewer even momentarily falls for the absurd proposition that von Sydow “is” Christ.

Just as Jesus films cannot avoid the problematic body of the actor, so too must they deal with the anti-Jewish polemic integral to the four Evangelists’ accounts of Christ’s death. Adele Reinhartz surveys how filmmakers have tried to mitigate the Gospels’ representation of Jewish culpability for the Crucifixion or, alternatively, have exaggerated the recriminations in accordance with later Christian teaching and anti-Semitic stereotypes.

Whereas Blaetz and Reinhartz discuss problems pertinent to all Jesus films, Christopher Fuller focuses on the sole masterpiece of the genre, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1964 feature, The Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Pasolini simultaneously refuses illusionist pretensions and specious claims of historicity, choosing instead to emphasize the artifice of cinematic representation, indeed of narrative itself. The casting of local, nonprofessional actors, the identifiable twentieth-century, if rustic, landscape, the carefully crafted citations—or, rather, vernacular transpositions—of Italian Renaissance paintings, the eclectic musical score, and the camerawork and editing all work together to deny the fantasy of a pure, unadulterated story distinguishable from its telling. Contrary to oft-repeated assertions of the film’s fidelity to the Gospel text, Fuller shows how Pasolini’s substantive omissions and rearrangements reinterpret (indeed revise) that text, effectively desacralizing the person of Jesus. Similarly, Pasolini invokes the tradition of sacred art to interrogate the Christian triumphalism that two millennia of storytelling about Jesus had made an inseparable part of the narrative. At the same time, Fuller reveals how the film registers Pasolini’s profound personal ambivalence toward Jews. Christ’s antagonists, the Jewish leaders, wear striking costumes that unmistakably identify them with Byzantine rulers of the Holy Land as portrayed in a famous ensemble of frescoes painted ca. 1466 by Piero della Francesca. Pasolini thereby assimilates his critique of power with a critique of Judaism and Jewish enmity, again a rhetorical move whose long and ongoing life is the subject of the volume’s epilogue.

Part Three explores Jewish reaction to and thematic appropriation of the Passion. Marc Saperstein outlines shifting positions in relation to culturally available critical tools. In the Middle Ages, for example, Jewish writers did not deny that their ancestors sought Jesus’ death, but maintained that they had acted according to Jewish law. Medieval Jews, moreover, could not fathom the logical incoherence of Christian theology: if God the Father required his Son’s sacrificial death, should the Jews be blamed for carrying out His will; should they not rather be praised? Only in the nineteenth century did Jewish historians, applying philological methods to ancient sources, put Jesus’ crucifixion in the context of Roman occupation so as to clarify the lines of power exercised by the Temple priesthood, the court of the Sanhedrin, and the ruthless foreign governor, Pontius Pilate. The portrait of an ambivalent, weak Pilate manipulated by Caiaphas into abandoning the dictates of his conscience and appeasing a bloodthirsty Judean populace was debunked as “merely legendary” (as Heinrich Graetz, 1817–91, diplomatically phrased it). The recognition that Pilate alone stood responsible for the penalty he meted out made possible a bold move. Responding to the waves of pogroms that engulfed eastern European communities following World War I, Jewish intellectuals took symbolic capital heretofore the exclusive property of Christians and turned the Christ-killer charge on its head. The Passion of Jesus, a Jew, became a metaphor for Jewish suffering at the hands of those who kill in Christ’s name. The archetypal martyrdom that for nearly two thousand years had framed the Christian discourse of suffering thus entered the vocabulary of Jewish thinkers speaking in Jewish terms about the history of their own people.

“The Passion of Passions” is how in 1955 the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas referred to the Holocaust, the horrors of which he refused to reduce to “spectacle,” to “the vanity of an author or director.” Lisa Saltzman relates Levinas’s ethical stance to the monumental project of the abstract expressionist painter Barnett Newman, whose cycle of fourteen black-and-white canvases entitled Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani (1958–66) is resolutely anti-iconic even as it depends on allusion to narrative and scriptural text for the generation of meaning. What distinguishes Stations of the Cross from other twentieth-century gestures to the Passion theme is Newman’s simultaneous invocation of the suffering subject through the searing pain of the Psalmist’s agonistic question, “Lema Sabachthani [Why hast thou forsaken me]?” and an absolute repudiation of its figuration. The critique of representation as an aesthetic practice fundamentally incompatible with sheer desolation, with the “why” cried out by six million voices, here achieves the transcendence of the second commandment. Graven images, the Mosaic injunction proclaims, inevitably become false gods.

It is one of the stranger twists of history that the Jews, whose self-definition as a people originated in renouncing the figuration of the divine, whose idea of the holy exceeded the limits of embodiment, became indelibly associated with attachment to the material order, idolatry of the letter, and the externals of empty formalism; correlatively they stood for blindness to spiritual truth and rejection of higher, invisible realities. It is one of the more bizarre paradoxes that a tiny people repeatedly conquered, exiled, and subject to the tensions at play in host cultures likewise came to incarnate the predatory lust for and tyrannical exercise of power. What accounts for these paradigmatic reversals, for their mutation from religious into secular categories, for their penetration of societies where real, live Jews were in fact a negligible, subjugated minority or, more tellingly, had never established a presence? In the epilogue, David Nirenberg unravels the metaphysical conflict for which the Passion story became an enduring social allegory. The vision of a carnal, hostile, and corrupting Judaism, arguably already incipient in the Pauline epistles and the Gospels, not only achieved canonical status in the church by the second century. Elevated into a malleable cosmological principle, it eventually enjoyed a global reach capable of myriad applications. Islam (from its very foundation), Enlightenment humanism, Marxism, Nazism, and postmodern idealisms of both the left and right—however otherwise discordant—have in common with Christianity a logic that conceives the enemies of truth as “Jews” and defines the evils of a pernicious materialism as “Jewish.” Sadly, the tenacity of this explanatory framework and its utility to religious and political discourse would guarantee the survival of anti-Semitism even if world Jewry were to disappear.

If, as the ensuing essays demonstrate, every act of representation is programmatically embedded in its own historical moment, if every rehearsal of the Passion story performs Christianity’s founding crisis in the present tense, then does it not behoove us to reflect upon the continuing power of that drama in our own pluralistic society? Consider the impact of Gibson’s film in the United States during the spring of 2004. Its promotion and consumption did not result in violence; no rock throwing, no setting of fires. But Americans nonetheless did engage in ritualistic behavior that bore a distant, shadowy resemblance to past rhythms. We normally experience “the movies,” especially ones pumped up by Hollywood stardom, as a highly commercialized medium of banal entertainment, democratic in its culturally leveling effects. Gibson’s celluloid theodicy, on the contrary, polarized the nation, demarcating the faithful from nonbelievers, insiders from outsiders. As block-ticket purchase and pious sentiment turned theaters everywhere into places of worship, the familiar scene of moviegoing initiated a dynamics of identity formation along starkly drawn religious lines. A groundswell of bonding across Christian denominations occurred at the expense of Jews, for whom the cross does not signify universal redemption but centuries of persecution. Moved from the private setting of properly religious venues into the proverbial “public square,” Gibson’s Passion replay staked for the Lenten/Easter season an irreducible divide between Christians and Jews on the civic landscape. Defenders of God and the gospel truth rallied their troops to make sure that the film’s financial success stood in for the victory of Christians over Jews. Sensationalize the visual rhetoric, invade municipal space, saturate the media, amplify the volume, and voilà, the Passion story mutates to reveal its millennial toxicity. Of course attention dispersed, emotions ebbed, and national conversations returned to business as usual. Despite the film’s remarkable popularity, it failed to inaugurate a new genre of public religious spectacle that would cyclically fracture the American body politic. Let us not, however, take recovery from the Passion wars smugly for granted. Rather, the episode should put us on notice: given the opportunity, the raw passion of religious conviction will alienate communities and galvanize animosities in twenty-first-century America as it has at other times, in other societies.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.