Medical Caregiving and Identity in Pennsylvania's Anthracite Region, 1880–2000

Karol K. Weaver

“Karol Weaver spins a compelling tale about the practice of vernacular medicine among the immigrant communities of Pennsylvania’s anthracite region. Using oral interviews, advice manuals, hospital records, folklore, and social science literature, she demonstrates the significance of ethnicity, gender, age, and religion in the access to and delivery of folk therapies and medical treatment during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While women acted as healers to family members and neighbors, providing herbal remedies and midwifery and caregiving services, men, as miners, faced myriad ailments that they self-treated with alcohol, tobacco, and patent medicines. These southern and eastern European immigrants made use of traditional Pennsylvania Dutch healers (powwowers) and also sought out faith healing to treat a variety of maladies. While the histories of mining and labor in the anthracite region of Pennsylvania have been well documented, much less is known about medical practices among working-class immigrants. Weaver’s well-researched and clearly written monograph goes a long way toward filling that gap in the scholarship.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Karol Weaver spins a compelling tale about the practice of vernacular medicine among the immigrant communities of Pennsylvania’s anthracite region. Using oral interviews, advice manuals, hospital records, folklore, and social science literature, she demonstrates the significance of ethnicity, gender, age, and religion in the access to and delivery of folk therapies and medical treatment during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While women acted as healers to family members and neighbors, providing herbal remedies and midwifery and caregiving services, men, as miners, faced myriad ailments that they self-treated with alcohol, tobacco, and patent medicines. These southern and eastern European immigrants made use of traditional Pennsylvania Dutch healers (powwowers) and also sought out faith healing to treat a variety of maladies. While the histories of mining and labor in the anthracite region of Pennsylvania have been well documented, much less is known about medical practices among working-class immigrants. Weaver’s well-researched and clearly written monograph goes a long way toward filling that gap in the scholarship.”

“Finally, a scholar has tackled in rich detail the meeting of folk and modern medical beliefs and practices during international migration. Medical Caregiving and Identity in Pennsylvania's Anthracite Region is a valuable introduction to the powwowers, wise neighbors, midwives, regional hospitals, and mining company and immigrant doctors who offered mining communities a panoply of changing health care choices. This book is highly recommended for anyone interested in the social history of U.S. immigration.”

“Many thousands of immigrants found work in the coal mines of central and eastern Pennsylvania around 1900. . . . [Karol K. Weaver] provides great details about the customs and practices that the immigrants and their families observed to overcome minor and even severe medical problems during those early years. This is the first major book to focus on medical care in the coal regions of the late 19th and 20th centuries.”

“Medicine is as much an art as it is a science. It is this subject of medicine as art that Karol K. Weaver covers in her excellent new study Medical Caregiving and Identity in Pennsylvania's Anthracite Region. . . . Well written and researched, it should be included on every reading list dealing with American social and labor history, as well as health care delivery.”

“Weaver’s book . . . is a fascinating read and contributes to the growing body of literature on local medical cultures in the United States and their transformation over time. The author convincingly demonstrates the importance of medical practices to ethnic identity, and the crucial roles of gender and religion in popular healing.”

“In Medical Caregiving and Identity in Pennsylvania’s Anthracite Region, 1880-2000, Karol Weaver skillfully weaves history and the lives of medical caregivers together within the context of policy, class, gender, and a transcultural society.”

Karol K. Weaver is Associate Professor of History at Susquehanna University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 The Anthracite Coal Region

2 Professional Medicine in the Anthracite Coal Region

3 Mothering Through Medicine: The Neighborhood Women

4 Powwowers and Pennsylvania German Medicin

5 Miners, Masculinity, and Medical Self-Help

6 Moving from Traditional Medicine to Biomedicine

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Growing up in the anthracite coal region of Pennsylvania, I heard stories about my nonna (grandmother) offering medical services to her neighbors. My mom told me that my nonna went up the bush to collect greens, which she then boiled into a tea and distributed to neighbors suffering from infections. My mother also said that my nonna walked miles to care for a friend dying from cancer. She tended sick neighborhood children and, in so doing, comforted their overworked mothers and fathers.

There were many caregivers like my immigrant grandmother—men and women, educated and uneducated, foreign born and American—who willingly and compassionately served the medical needs of their own families and those of their neighbors. In the pages that follow you will learn that the simple story my mother told me demonstrated that the way one takes care of the body and the soul (whether your own or another’s) defines who one is and who one can become.

The history of medical caregivers like my nonna shows that medicine shapes one’s identity. Immigrants and native-born Americans in the anthracite coal region of Pennsylvania sought medical care from neighborhood women, Pennsylvania German powwowers, American physicians, and immigrant doctors. While most immigrants ultimately abandoned their medical customs, Pennsylvania Germans retained their traditional medical system because of their creation of a strong ethnic identity. Similarly, Italian Americans remained committed to their medical customs because of their ability to honor their Italian ancestry while simultaneously adhering to American values. Over time, biomedicine became the hallmark of an assimilated American.

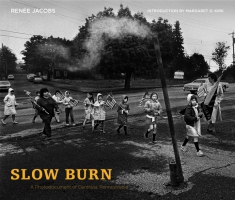

The influx of “new immigrants” from eastern and southern Europe to Pennsylvania was immense. Between 1899 and 1914, more than 2.3 million immigrants contributed to making Pennsylvania one of the nation’s industrial powerhouses. Drawn by the promise of work, many immigrants made the anthracite coal fields of northeastern Pennsylvania their destination. Despite good pay, miners faced long periods of unemployment as a result of overproduction. Unsafe working conditions were the norm, and the threat of mine accidents was ever present. Breaker boys sifted coal from slate, rock, wood, and slag, and men died prematurely from the coal dust that clogged and scarred their lungs. Living conditions were also quite poor; company housing and high prices at the company store kept miners tied to the powerful and unforgiving mine companies. Moreover, class distinctions based on where one figured into the coal economy divided residents. The area also was a diverse blend of ethnicities and religions. Descendants of English, Welsh, German, and Irish immigrants inhabited the area, as did the new immigrants. Catholics outnumbered both Protestants and a small community of Jews. These ethnic, religious, and class divisions affected the type of medical care provider a coal region resident chose.

Neighborhood women were medical caregivers who lived and worked in the anthracite coal region. They provided domestic medicine, which meant they used both homemade and store-bought remedies, performed minor surgery, served as midwives, and offered spiritual and emotional comfort to their clients. Residents of the coal communities recognized these women as medical caregivers and sought them out when they were ill. Both American-born women and new immigrants served as community caregivers, and their training ranged from practical experience to formal education. Using domestic medicine, these women extended their maternal roles beyond the confines of their own homes and out into the homes of their neighbors and into the corner stores that anchored that region’s neighborhood. Yet as the maternal roles of women changed during the second half of the twentieth century, much of the work once completed by neighborhood women came to be done by family doctors.

Neighborhood women generally offered care to other women and to children. Men, especially miners, practiced medical self-help—they took responsibility for their physical problems. Specifically, they employed alcohol, tobacco, and patent medicines to deal with black lung and with the wounds they incurred while working. They obtained these items from local taverns and corner stores and via mail order companies. Their medical independence and the spaces where they obtained medical relief reflected the types of masculine behavior expected of men and boys in coal country. Although alcohol and tobacco were recognized elements of the American pharmacopoeia, miners were criticized for their use of these items, charged with intemperance and economic wastefulness, and their medical needs, especially in regard to black lung, were ignored or dismissed.

The anthracite coal region not only was home to new immigrants, but also sheltered other ethnic minorities. For centuries, the fertile soil of Pennsylvania and the state’s dedication to religious freedom sustained Pennsylvania Germans. New immigrants looked to Pennsylvania Germans for spiritual and medical assistance because powwowing, the traditional medical system that Pennsylvania Germans embraced, echoed the healing customs of the Old World. While accepting aspects of modern American medicine, coal region residents relied on powwowing. Yet the popularity of powwowing was not the result simply of immigrants seeking out Pennsylvania German healers. Pennsylvania Germans equated the medical techniques offered by new immigrant caregivers with powwowing, described the foreign healers as powwowers, and sought them out for medical and spiritual relief. Thus, the self-imposed cultural and social isolation and centuries-old resistance to assimilation that characterized the Pennsylvania German community as well as the influx of new immigrants allowed powwowing to survive the onslaught of modern medicine and to remain a medical choice for many inhabitants of northeastern and central Pennsylvania.

Although new immigrants called on neighborhood women and powwowers for medical assistance, they also turned to physicians for help. They consulted American doctors during medical emergencies, for routine shots, and for surgical procedures. They also sought care at local hospitals and depended on voluntary insurance associations to see them through times of trouble. By the mid-twentieth century, physicians from the Old World had journeyed to the United States to serve the new immigrants and their families. Both foreign-born and American physicians became respected members of anthracite communities because of the strides that medicine had made in the period after World War II. By the second and third generations, the new immigrants proudly claimed descendants who were now assimilated as practitioners into the biomedical model that dominated American medicine.

The story of medical caregiving in the anthracite region will build upon the work done by scholars who specialize in the history of medicine as well as the history of Pennsylvania. Most scholars who have studied the history of the anthracite coal region emphasize male coal miners, especially their participation in strikes and labor associations. The history of the Pennsylvania coal fields also normally concerns the contributions of immigrants to the growth of Pennsylvania as the industrial workshop of the United States. When historians have considered health care in Pennsylvania mining communities, they have concentrated on the history of dangerous working and living conditions and the hazards of black lung. Biographies of doctors who served the coal communities exist, but literature on medical work completed by immigrant and Pennsylvania German caregivers is sparse.

More generally, my project will add to what we know about transcultural medicine in the United States. Many medical professionals who treated immigrants dismissed the ways their patients understood and dealt with disease. Cultural and language barriers made their tasks especially difficult. Doctors’ reputations were on the rise following the impressive results of the bacteriological revolution, and the standards of medical professionalism were being solidified through improvements in medical education, licensing requirements, and the power of medical organizations. The gospel of scientific and medical progress attracted local, state, and federal governments, which tried to implement American principles of health and hygiene. The governments often demonized as unscientific, backward, and dangerous the accepted folk wisdom of immigrants and powwowers.

This book also addresses issues of identity formation among ethnic groups. When scholars have considered the formation of identities, they have not devoted much attention to medicine. Instead, they focused on other factors, such as food customs, religion, and music. For example, historians and anthropologists studied the importance of food in the establishment of ethnic identity as well as integration into American society. As immigrants came to the United States, they encountered new foods and, thus, established new identities. The hunger they experienced in the Old World contrasted sharply with the promise of plenty that they hoped for in the New World. With this constant stream of newcomers, the American table paradoxically has been replete with standardized products on one end and abounding with diverse ethnic dishes at the other end. Writers also considered the roles that religion plays in creating an ethnic identity and in the Americanizing process. Some authors traced how ethnic groups navigated assimilation while still retaining strong ethnic identities through their deep connections with religion and religious institutions. Others delved into how religious holidays, festivals, and devotion contribute to the formation of a clearly defined ethnicity. Researchers also have investigated how music shaped ethnic and working-class identity. Specifically, folklorist George Korson recorded the ballads of the coal region and discovered how music created a laborer’s identity, connected the laborer with his nationality, and helped the singer and listener to navigate the difficulties of Pennsylvania’s mining world. Despite this impressive work on ethnic identity, few scholars have considered medicine and medical caregiving. Commenting on the dearth of scholarship, historian Robert Orsi stated, “The subject of immigrant vernacular healing awaits a study of its own.” The present book fills that need.

To highlight the connections between identity formation and medicine, the book not only considers ethnicity but also takes into account the important roles that gender, space, religion, and age played in the lives of coal region men and women. The type of medical caregiving one sought or practiced was shaped profoundly by one’s gender. Scholars define gender in a variety of ways. Some thinkers conceive it as the expectations that society places on men and women. These obligations then make up what is considered masculine or feminine behavior. Scholars also assert that gender is performed, repeated, and ritualized by individuals. These performances then set the standards for masculinity and femininity. I will use the term gender in this book to describe the expectations society places on men and women and the ways individuals perform activities to adhere to or challenge these expectations. Furthermore, in this study, one will see that gender is shaped by the class, ethnic, and generational experience of given historical actors.

Space adds another dimension to the book’s analytical framework. Men, women, and children in the anthracite region received medical care in various settings from different types of practitioners. Formal medical settings included miners’ hospitals, doctors’ offices, patients’ homes, and the sites of life-threatening accidents. Informal medical spaces sometimes overlapped with formal places of care. Informally trained medical caregivers offered their services in patients’ sickrooms and wherever bodies were injured and broken. But kitchens functioned as medical spaces too—coal region women fashioned remedies made from plants and herbs collected in their gardens and in the woods that surrounded their homes. Mines, bars, drug stores, corner groceries, and the post office also constituted medical spaces for the inhabitants of the coal fields of Pennsylvania.

Religion also shaped the identities of residents of the coal region and influenced the medicine they employed. One’s dedication to a particular religious tradition affected a person’s willingness to rely on spiritual forms of healing, among them prayer, the laying on of hands, and the removal of the evil eye. Roman Catholicism dominated the area’s cultural landscape, although assorted Protestant churches existed amid the Catholic steeples and the Orthodox onion domes. The spiritual medicine embraced by coal region men and women incorporated the prayers and symbolism of the Roman Catholic Church. Yet church officials sometimes frowned upon the folk medical practices of miners, their wives, and other members of their families. Leaders of the Protestant and the Catholic churches frowned on the heavy drinking of men and boys, but the males knew that alcohol relieved their physical and mental burdens. Healers who removed the evil eye or who practiced powwowing worried about how their medical techniques appeared to local clergymen and sought their consent to continue practicing.

Age was another important factor in the lives of coal region residents and the types of medical caregiving they provided and employed. Like gender and ethnicity, age is socially constructed. Certain stages of one’s life compel that behavior meets social norms. Likewise, one’s age dictates the types of employment in which one participates. Further, age intersects with gender and ethnicity and, as a result, people grow old in myriad ways. In the tradition of the pathbreaking work of Kathy Peiss and Sarah Chinn, this book investigates how generational differences influenced American and ethnic identities; unlike these authors, who focus largely on leisure, I see identity as shaped by medical choices as well. Age affected medical care and the individuals who provided it. Company doctors and lodge physicians focused their care on grown men; as a result, women and children sought help elsewhere, usually at the hands of female practitioners of domestic medicine. The high status afforded to neighborhood women rested upon their care of neighborhood children. As neighborhood women aged, the infirmity that often accompanied age diminished their ability to provide for their neighbors. This fact, along with the generational differences between first-generation immigrants and their American daughters, led to the disappearance of folk medicine. Specifically, twentieth-century parenting advice encouraged mothers to focus on their own children and not the children of their neighbors. Moreover, motherhood in the twentieth century was characterized by the ability to purchase consumer items for one’s children; such consumer items included visits to physicians and purchases at the corner pharmacy. As the century progressed, medical specialties tied to the age of the patient grew in importance; in fact, pediatrics and gerontology shaped American perceptions of childhood as well as old age. Scientific and medical experts felt confident telling parents how to raise their children and advising adult daughters and sons about the proper care for elderly loved ones.

As a regional study, this book depends on local history as a vehicle for understanding economic, social, and, most important, medical trends that affected the nation as a whole. Over the course of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, industries such as coal mining flourished and then declined. Women’s entrance into the workforce accompanied the swift ascent and descent of coal mining. The industrialization and deindustrialization that the anthracite region experienced affected communities across the United States and ultimately influenced the practice and prestige of medicine.

In addition to highlighting economic factors, this local history focuses on social concerns, namely immigration and changing expectations of masculine and feminine behavior. The development of the anthracite region is a small, yet important, example of the contributions that new immigrants made to the American economy, culture, society, and medicine. The ability to adapt to and assimilate American qualities while retaining ethnic characteristics is exemplified in the immigrants’ reactions to and involvement in the medical life of their community. Like ethnic identity, gender identity was a social factor that influenced the lives of Americans. Over the course of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the lives of American men and women altered as different behaviors were expected of them. Similarly, the social roles of men and women in Pennsylvania coal country were transformed in relation to industrialization and deindustrialization.

Finally, this local history is a fitting model of revolutions in medicine and medical practice. Biomedicine grew in stature during the twentieth century as a result of important gains in therapeutics. The rise of the United States as a world power cemented its leadership role in medical science and technology. Closer to home, economic and social changes, specifically deindustrialization, women’s changing domestic and work roles, and assimilation, led to the disappearance of domestic medical therapies, especially those that relied on natural ingredients and those that depended on time and feminine sociability. A country that once depended on medical self-care increasingly turned to doctors and other medical specialists to serve its needs.

Besides local history, this book relies upon the historical method of biography to tell the story of medical care in the coal region. To bring readers into the region’s diverse medical world, I introduce them to specific men and women who acted as medical caregivers. Thus, the reader comes to know Maria Bridi, a foreign-born neighborhood woman, and her American neighbor, Blanche Paul, who like Bridi functioned as an herbalist. Similarly, Mr. Carl shows the reader what Pennsylvania German powwowers did for the residents of the coal region. Finally, the medical career of Vincenzo Mirarchi demonstrates how foreign-born and professionally trained physicians acted as bridges between Old World medical caregiving and New World biomedicine. I came to know these and other intriguing individuals as a result of the oral history research I completed. I spoke to men and women treated by the medical caregivers who are the subject of my book. I met and talked with the family members of domestic as well as professional caregivers. I consulted with men and women who practiced natural and spiritual forms of domestic medicine. Their rich storytelling helped me to understand that medicine is a fundamental element in the formation of identity.

The interviews I have completed, however, are not the only sources on which this work depends. Medical handbooks also offered significant bodies of information. For centuries, domestic medical practitioners relied on manuals for medical advice. Two handbooks have proved essential to my study. The first, La donna, medico di casa, was a popular medical tome used by Italian immigrant women. The other text, Der lang verborgene Freund, had been a mainstay of the powwowing community since the nineteenth century.

Official reports from local miners’ hospitals such as the State Hospital for Injured Persons of the Anthracite Coal Region of Pennsylvania at Fountain Springs also proved to be valuable. They provided information about the early struggles as well as modest successes that such institutions experienced over the course of the twentieth century. They also highlight the important roles that second-generation and immigrant doctors played as hospital staff members in the second half of the century.

Analyses of immigrant health written by social scientists and social workers helped me to understand how early twentieth-century professionals viewed foreign-born men and women, their disease patterns, and the medical care that they used. Some researchers compassionately sought to understand the medical customs and needs of the immigrants; others denigrated the foreign born and their medical customs as witchcraft and charlatanism.

The rich folklore of the coal region supplied a further source of information. George Korson’s unparalleled investigation of the music, humor, and stories of anthracite country provided data on how residents dealt with illness and death. Korson’s books, articles, and audio recordings showcase the creativity of the men and women of the coal region. While working as a journalist in Pennsylvania in the twentieth century, Korson traveled throughout the coal region collecting ballads, ghost stories, games, and recipes. Housed in the Library of Congress, Korson’s collection is an understudied treasury of coal region folklore. Similarly, coal region authors such as Eric McKeever provided stories from their childhoods that mirrored many of the themes—masculinity, violence, humor, and hard work—that Korson and other folklorists highlighted. Via humorous anecdotes, McKeever recorded the healing customs of residents. Finally, the work of folklorists who study Pennsylvania German culture contributed to my analysis of that community’s style of medical caregiving.

Along with the secondary sources compiled by historians and other scholars, these primary sources helped me to craft the intriguing story of medical caregiving in the anthracite coal region. In the following pages, I will be relating the history of Pennsylvania coal country, the biomedically trained American and foreign-born physicians who practiced there, and the informally trained medical caregivers who rendered aid to family members and neighbors. Chapter 1 highlights the anthracite region of Pennsylvania, providing an overview of the geography, economy, society, politics, and culture of the area. It ends with a discussion of the health dangers that miners and their families experienced.

Chapter 2 investigates the health professionals who served in the coal region and the health institutions established there, including company doctors, local miners’ hospitals, American doctors in private practice, and voluntary health and death benefits associations. Despite the great need for medical services, company doctors, hospitals, physicians in private practice, and medical practitioners hired by insurance programs were often not the first choice for medical care for the working men and women of the anthracite coal region. Suspicion, the lack of prompt service, different cultural practices, the focus on miners as the primary beneficiaries of care, and the miners’ desire to be treated in a more familiar way prompted them to seek the care of nonprofessional caregivers and to take personal responsibility for their own health care via medical self-help.

Chapter 3 introduces readers to the neighborhood women of the coal region. Neighborhood women were one of the most important sources of health care for the female residents and the children of the anthracite coal region. Working from their kitchens and gardens, these women offered various medical services to their own children and to their neighbors. By so doing, they shaped their maternal and feminine identities. Yet as the roles of women and mothers changed and the status of physicians improved during the second half of the twentieth century, much of the work they once completed came to be done by practitioners of biomedicine.

The medical care provided by powwowers is the focus of chapter 4. Both immigrants and native-born Americans sought help from powwowers, or medical caregivers who used both natural and spiritual remedies to treat illnesses, many of which were considered incurable by modern medicine. Powwowing remained a medical choice over the course of the twentieth century and still has practitioners and adherents today because of the ability of Pennsylvania Germans to retain their unique cultural characteristics. In addition, the use of powwowing by immigrants and the identification of immigrant folk healing as powwowing contributed to the survival of this distinctive medical tradition.

Chapter 5 continues the focus on gender delineated in chapter 3, but looks at men, masculinity, and medical self-help instead of women, femininity, and medical caregiving. Facing dire circumstances in the mines, men and boys depended on alcohol, tobacco, and patent medicines to deal with the ravages of black lung and the effects of wounds, both large and small. Their reliance on these items, especially drink and smoke, was subject to criticism by medical professionals and social workers who interpreted it as an excuse for drunkenness and free-spending.

The state of medical care in the anthracite region in the last quarter of the twentieth century and in the twenty-first century is the subject of chapter 6. As a result of economic, social, demographic, and medical changes, domestic caregiving faded away. Second-generation physicians and foreign-born doctors served as bridges between Old World folk medicine and American biomedicine. By the third generation, ethnic families largely did away with traditional therapeutics. American biomedicine took its place. Professional medical careers for the descendants of immigrants were well-respected and desired occupations. Instead of going into the factories as their mothers had done, many women decided to obtain nursing degrees at local hospitals. By the second and third generations, the new immigrants proudly claimed descendants who were practitioners of American biomedicine.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.