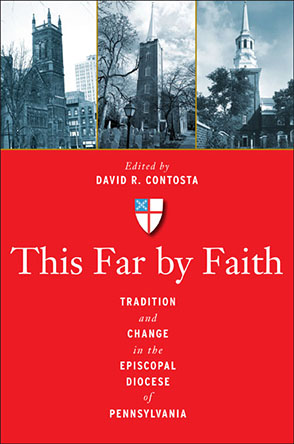

This Far by Faith

Tradition and Change in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania

Edited by David R. Contosta

This Far by Faith

Tradition and Change in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania

Edited by David R. Contosta

“With telling detail and compelling narrative, the essays in This Far by Faith track the origins and evolution of an important diocese that charted ‘a middle way’ for American Christianity over four centuries. Throughout the book the authors show a diocese struggling with such varied, but intersecting, issues as a changing geographical and demographic compass, race, doctrinal disputes, discipline, and personality. This Far by Faith opens the red door to the whole church, from pulpit to pews. In doing so, it provides a most sensitive and sensible examination of a diocese as a living organism. It also provides a model for writing church history hereafter. It is, then, a book that transcends its subject and invites anyone interested in American religion to consider its method and meaning.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Aside from the editor, the contributors are Charles Cashdollar, Marie Conn, William W. Cutler III, Deborah Mathias Gough, Ann Greene, Sheldon Hackney, Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner, William Pencak, and Thomas F. Rzeznik.

“With telling detail and compelling narrative, the essays in This Far by Faith track the origins and evolution of an important diocese that charted ‘a middle way’ for American Christianity over four centuries. Throughout the book the authors show a diocese struggling with such varied, but intersecting, issues as a changing geographical and demographic compass, race, doctrinal disputes, discipline, and personality. This Far by Faith opens the red door to the whole church, from pulpit to pews. In doing so, it provides a most sensitive and sensible examination of a diocese as a living organism. It also provides a model for writing church history hereafter. It is, then, a book that transcends its subject and invites anyone interested in American religion to consider its method and meaning.”

“This Far by Faith is a fine book. People interested in the history of American religion, in the history of Pennsylvania, and in the Episcopal Church will find it accessible and informative.”

“This volume not only notes the contributions of the various bishops but also focuses on lay leadership, institutional growth, and areas of conflict. It seeks to pay attention to the role of women and racial minorities; attempts to provide detailed demographic data; and endeavors to set events in the life of the church in the general social context. Episcopalians in the Diocese of Pennsylvania, students of American church history, and social historians should all find it to be a useful work.”

“What a good text this would make for a course on Episcopal Church history, or, for that matter, also American church history—even in a course on United States history.”

“It is a pleasure . . . to read this impressive and accessible diocesan history. . . .

“. . . This is an excellent history. It is critical to our understanding of the Episcopal Church nationally, and in many ways, constitutes a microcosm of American mainline religion.”

David R. Contosta is Professor of History at Chestnut Hill College.

Contents

List of Figures

List of Tables

List of Abbreviations

Introduction

David R. Contosta

1 The Colonial Church: Founding the Church, 1695–1775

Deborah Mathias Gough

2 From Anglicans to Episcopalians: The Revolutionary Years, 1775–1790

William Pencak

3 Identity, Spirituality, and Organization: The Episcopal Church in Early Pennsylvania, 1790–1820

Emma Jones Lapsansky-Werner

4 New Growth and New Challenges, 1820–1840

Charles D. Cashdollar

5 The Church and the City, 1840–1865

Marie Conn

6 The Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 1865–1910

Ann Norton Greene

7 The Church in Prosperity, Depression, and War, 1910–1945

Thomas F. Rzeznik

8 A Church on Wheels, 1945–1963

William W. Cutler III

9 Social Justice, the Church, and the Counterculture, 1963–1979

Sheldon Hackney

10 A Perfect Storm, 1979–2010

David R. Contosta

Contributors

Index

Introduction

David R. Contosta

The Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania—and its precursor, the Church of England in colonial Pennsylvania—have been shaped by complex historical forces. These include the history of Christianity, especially during its first centuries, the foundations of the Church of England in the sixteenth century, patterns of colonial society, an evolving American culture, world events, and life in southeastern Pennsylvania, where the diocese has been centered.

Local Episcopalians have also been part of a national church that over the past two centuries has often been informed by dual impulses. Their church has seen itself as both Catholic and Protestant—a “reformed” church that claims apostolic succession for its bishops but allows for a large degree of decentralization and governance by the laity. Despite Episcopalians’ strong roots in the Church of England, they eventually came to see themselves as the most American of all Christian denominations. This claim stemmed in large part from the disproportionate number of Episcopalians in national leadership positions. Of the forty-four presidents of the United States, eleven of them, or 25 percent, have been Episcopalians, although Episcopalians have never made up more than 3 percent of the U.S. population. The decision by the Episcopal Church in the early twentieth century to build the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., often the setting for funerals and other services involving high-ranking officials, is a powerful symbol of its claim to be the national church of the United States.

Another duality has involved the Episcopal Church’s emphasis on tradition, combined, in the best of times, with an openness to change as the wider culture presents new challenges. Tradition is grounded especially in the basic faith statement of the Nicene Creed and in the Book of Common Prayer. But respect for reason, as a divine gift and as an appropriate tool for reconciling tradition with present reality, has saved the denomination from rigid traditionalism. Episcopalians have approached the Bible in a similar spirit: different persons derive various meanings from scripture, and the Bible needs to be interpreted in the light of modern life. The Book of Common Prayer, which draws heavily on the Bible, also permits some latitude. While the words of the liturgy will be the same in every parish, actual worship practices might vary from Anglo-Catholic, at one end of the spectrum, to evangelical at the other.

This “latitudinarian” approach to faith and worship has been part of the Church of England (and of the larger Anglican Communion, of which the Episcopal Church is now a part) since Queen Elizabeth I embraced a middle way that came to be known as the Elizabethan Settlement. This middle way has been one of the glories of Anglicanism, but it has also opened the door to controversy in every era. Without an infallible pope or a belief in a literal and unchanging understanding of the Bible, Episcopalians have been free to disagree about both faith and action. Yet, as one historian of the Episcopal Church has written, “Controversy is unpleasant but it is often a sign of life. A peaceful church is one that is slowly dying.”

In the end, the Church of England’s middle way and conditions in colonial Pennsylvania meshed very well. Pennsylvania was the quintessential “middle colony” and then, following independence, “middle state.” Quaker tolerance did not allow for an established church in Pennsylvania. The Quakers’ belief in human equality, combined with their practice of toleration, also meant that immigrants were welcome from all over western Europe, making Pennsylvania a precursor of the religious and cultural diversity that would come to characterize the entire United States. Though members of the Church of England in colonial Pennsylvania were initially unhappy about their status as just one religious group among others, they eventually accommodated themselves to the situation.

Pennsylvania’s middling position, geographically and culturally among the original states, made it the obvious place for founding the Episcopal Church after the American Revolution. William White, the rector of Christ Church, Philadelphia, and the Diocese of Pennsylvania’s first bishop, was able to use his sense of a middle way and a genius for compromise to persuade southern members of the faith, long wedded to lay control of their church, to accept bishops, without which the New Englanders would not have joined the fold. Meeting at Christ Church in 1789, the same year that the new Constitution of the United States of America took effect, White presided over the birth of the national church. Just five years before, in 1784, he had coaxed the Diocese of Pennsylvania into being. White’s newly minted diocese became the “mother diocese” of the Episcopal Church, while his Christ Church became the mother church of the entire denomination.

This history of the Diocese of Pennsylvania, especially during its earlier years, is in many ways a history of the Episcopal Church at large. Even in more recent years, as it remains one of the largest and most influential dioceses in the national church, its story has paralleled and illustrated the challenges and accomplishments of the wider denomination.

In chapter 1 of this volume (1695–1775), Deborah Mathias Gough examines the difficulties and anomalies that members of the Church of England faced in colonial Pennsylvania. During their first few decades, they campaigned to have Pennsylvania made into a royal colony, which would have deprived the Penn family of its proprietorship. They also petitioned the Church of England to send them a bishop. They failed on both counts, and by 1715 they had reconciled themselves to accepting religious pluralism and recognizing other denominations as legitimate. The church succeeded in attracting the small numbers of Swedish Lutherans in southeastern Pennsylvania, but the more numerous German Lutherans resisted calls to join. Clergy shortages plagued the Church of England in Pennsylvania throughout the colonial period, as did the lack of a bishop to supervise clergy and enforce order within the church.

William Pencak, in chapter 2, looks at how the crisis of the American Revolution (1775–1790) affected members of the Church of England, whose liturgy required prayers for the British monarch and whose clergy had had to swear loyalty to the Crown. Because of this, clergymen were automatically suspect among supporters of the Revolution, whether or not they were loyal to Britain. Thanks to the common sense and leadership of William White, the Diocese of Pennsylvania and a separate Episcopal Church were established during this period. As such, the Episcopal Church became the first of many autonomous churches within what would later be called the Anglican Communion. In the spirit of the new American Republic, both the diocese and the national church mandated the election of bishops and a bicameral legislative body, with wide representation for lay members. Although centered in Philadelphia, the new Diocese of Pennsylvania covered the entire commonwealth until the diocese was subdivided many years later.

In chapter 3, Emma Jones Lapsansky-Werner examines the diocese during its first three decades (1790–1820). Although they had declared their independence from Great Britain, Episcopalians were still sometimes stigmatized because of their prior connections to the Church of England and its now unpopular monarchy. As an urban-centered church, many of whose members were prosperous, the Diocese of Pennsylvania often had a hard time relating itself to the less prosperous rural population elsewhere in Pennsylvania. The diocese also had difficulty competing with other denominations, such as the Methodists, who preached a simple but often inspiring message without the need for a highly structured liturgy, or even a church building in which to preach. Many African Americans felt more comfortable with the informal ways of the Methodist clergy than they did with the more formal Episcopal Church. Indeed, it took Bishop White ten years to raise Absalom Jones, the leader of the all-black African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, from deacon to full-fledged priest, and Jones was never seated at a diocesan convention, as were all white clergy. Racial prejudice and segregation would continue to plague the diocese in the years to come.

Charles D. Cashdollar tackles a period of growth and new challenges for the Pennsylvania diocese in chapter 4. During the twenty-year period 1820–1840, the number of parishes doubled, and Pennsylvania’s population spilled out into the central and western counties of the commonwealth. But much of this growth took place in Philadelphia, as groups of men decided, all too often, to start a new parish within just a few blocks of another Episcopal church. The diocese adopted a laissez-faire approach to this development, a position that would come back to haunt future bishops, who would face a shrinking urban population and demographic changes unfavorable to membership in the Episcopal Church. During this same period, the high-church Oxford Movement began to attract many in the diocese, touching off a protracted struggle between them and low-church adherents.

While the diocese continued to be rent by disagreements over worship style, Philadelphia was rocked by racial and religious conflict, described by Marie Conn in chapter 5 (1840–1865). The diocese was not involved in the violence that too frequently accompanied this conflict, but it attempted to deal with some of the underlying causes of urban strife by creating a number of institutions to address contemporary problems and needs in an organized way.

Ann Norton Greene takes on an especially rich period in diocesan history (1865–1910) in chapter 6. Membership surged during the so-called Gilded Age, as newly rich men and women found the respectability and orderly worship of the Episcopal Church a fitting match for their rising social status. Quarrels continued between the high- and low-church factions, however, leading to the foundation of the Reformed Episcopal Church in 1873, which a small number in the diocese left to join. Greene concludes her chapter with a discussion of the Social Gospel Movement, one of the central forces in the Progressive Era.

During the period 1910–1945, Thomas Rzeznik explains in chapter 7, new parishes were formed, and the diocese laid plans for a huge cathedral in Roxborough. Episcopalians reached the zenith of their influence in these decades, laying claim more than ever before to being the “nation’s church.” The building of the George Washington Memorial Chapel at Valley Forge was a physical manifestation of this attitude. At the same time, however, attempts to establish more central authority over the diocese were sometimes resented and even resisted at the parish level. The Great Depression and the two world wars, by contrast, fostered a strong sense of collective mission—though some clergy thought it wrong to glorify war or to politicize the work of the church, especially during World War II.

During that war and the postwar period (1942–1963), with its crusade against Communism, many Americans turned to religion. The Pennsylvania diocese saw significant growth, especially in the suburbs outside Philadelphia. Some critics lamented that the suburban churches were cut off from the city, content to ignore poverty, racial injustice, and other urban problems. The diocese and the national church were also slow to address questions of gender inequality. William Cutler explores these issues in chapter 8.

The period 1963–1979, addressed by Sheldon Hackney in chapter 9, was a study in contrasts. Bishop Robert DeWitt plunged into a fight for social, racial, and gender justice that alarmed many members of the diocese. There was particular anger over DeWitt’s acceptance of the Black Manifesto, which demanded massive monetary reparations from the white churches for historic and ongoing discrimination against African Americans. DeWitt also participated in the first ordination of a woman priest, in defiance of tradition and without the blessing of the national church. A significant number of members were so angry with their bishop that they stopped making pledges or left the denomination altogether. At the very end of DeWitt’s term as bishop, the Episcopal Church adopted and began using a new Book of Common Prayer.

The new prayer book, more thoroughly revised than any of its American predecessors, angered many Episcopalians in the Pennsylvania diocese and elsewhere. As David Contosta explains in chapter 10, this disaffection was one of several issues that created a “perfect storm” in the period 1979–2010. Continuing unhappiness over the ordination of women among a small but vocal minority, combined with the ordination of gay and lesbian priests in the diocese, led several parishes to withhold their contributions to the diocese. Some parishes attempted to leave the diocese altogether and to affiliate themselves with more conservative bishops in the United States or abroad. Dwindling membership in urban parishes had led the diocese to subsidize a number of these parishes. Decisions to close or merge such parishes, instead of continuing to support them with diocesan funds, led to considerable anger toward Bishop Charles Bennison. Despite this contention, Bennison and his predecessor, Allen Bartlett, succeeded in making the large Victorian Gothic Church of the Saviour into the diocese’s first cathedral.

Just how the most recent controversies would be resolved was unclear as the diocese moved beyond its 225th anniversary. It can at least be said that such controversy is no stranger to the Diocese of Pennsylvania. In the end, a middle way, in the best tradition of the Episcopal Church, might well offer answers that will prove acceptable to the great majority in the long run.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.