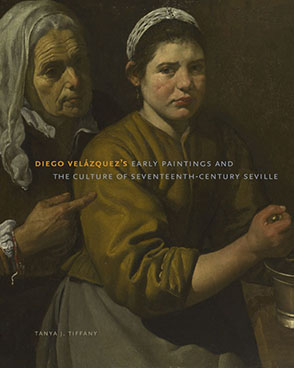

Diego Velázquez's Early Paintings and the Culture of Seventeenth-Century Seville

Tanya J. Tiffany

Diego Velázquez's Early Paintings and the Culture of Seventeenth-Century Seville

Tanya J. Tiffany

“Tanya Tiffany’s mastery of the documentary, historical, theological, ethnographic, and literary material of Africans in Seville is meticulous, broad, and thorough. This is a significant contribution to the field. It offers new interpretations and advances theoretical discussions of race, gender, iconographical description, intellectual life, and Velázquez’s historical stature in important paintings.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Tanya Tiffany’s mastery of the documentary, historical, theological, ethnographic, and literary material of Africans in Seville is meticulous, broad, and thorough. This is a significant contribution to the field. It offers new interpretations and advances theoretical discussions of race, gender, iconographical description, intellectual life, and Velázquez’s historical stature in important paintings.”

“Drawing upon a wealth of new sources, Tanya Tiffany has managed to reconstruct the social, intellectual, and religious world of Seville as it was when Spain’s most celebrated seventeenth-century artist lived there. Especially revealing are her detailed readings of his early works, his deservedly celebrated bodegones among them. The result is a strikingly original and wholly convincing understanding of this still poorly understood phase in Velázquez’s artistic career. This handsome volume deserves a place on the bookshelf of anyone seriously interested in Velázquez, let alone the art and history of Golden Age Spain.”

“Tanya Tiffany’s book is by far the most in-depth examination to date of Diego Velázquez’s early paintings in relation to the culture and society of early seventeenth-century Seville, Spain’s most cosmopolitan city in that period. Combining rigorous research and meticulous attention to pictorial composition, the chapters offer sustained, original analysis of works from all the major genres Velázquez cultivated in his formative years. Tiffany brings a commanding range of textual sources to bear on her analysis, including hagiographies, poetry, devotional manuals, and conduct books. The breadth of visual sources examined alongside the major paintings—prints, polychrome sculptures, and ephemeral paintings—is also impressive, transcending anachronistic divisions between popular and elite art in the early modern period. Throughout, Tiffany reconstructs as much as possible the original circumstances of Velázquez’s production. The result is a richly illuminating book about the social and cultural life of Velázquez’s early paintings and the world to which they belonged. It will thus be indispensable to students and scholars not only of art history but also of early modern Spanish culture more broadly.”

“Tiffany has written a book that supersedes all previous studies of the type and makes a major contribution to our understanding of the artist and his world.”

“For almost four decades, [the] focus on Velázquez’s activity in Madrid has produced an emphasis on patronage as an interpretive perspective, and simultaneously on the artist’s success in social climbing. Tiffany also covers patrons in Seville, and Velázquez’s connections to Juan de Fonseca certainly facilitated his later career. Tiffany’s detailed account of these and other Sevillian links make a substantial contribution in this area. Yet Tiffany’s most important chapters seek to reconstruct the social imaginary surrounding several major Sevillian paintings, where she connects these works to gender roles, race, and the problem of controlling sexual desire among the devout.”

“Throughout this beautifully illustrated and exhaustively documented book, Tiffany highlights ‘the inseparability of the young Velázquez from the visual and intellectual culture of early seventeenth-century Seville’ and successfully shows how the ‘Sevillian foundations of his art’ had a lasting impact in his later career at court. While this in itself is not new, Tiffany brings a fresh understanding of the conditions that made it possible. Her examination of a wide variety of textual and visual sources alongside Velázquez’s paintings from this period, for instance, transforms the long-held but poorly understood notion of Velázquez’s erudition—often associated with Velázquez’s later career in Madrid but, as demonstrated here, deeply rooted in the artist’s Sevillian period. Furthermore, Tiffany also contributes to the reassessment of Pacheco, who emerges as an effective teacher completely in tune with the artistic debates of the day (foremost the question of naturalism) and a crucial player in Velázquez’s artistic development, both through his teachings and through his connections with Seville’s religious and intellectual elites. By bringing attention to these connections, moreover, Tiffany sheds light on the vibrant culture of seventeenth-century Seville and its social, artistic, and religious realities (including rarely discussed contemporary theories of race). Ultimately, by situating Velázquez’s works in dialogue with this context, Tiffany also challenges the tendency to isolate the artist from the Spanish artistic context. In this way, rather than standing in opposition to the rich culture of Seville, he becomes its most eloquent interpreter.

“Diego Velázquez’s Early Paintings and the Culture of Seventeenth-Century Seville has wide-ranging methodological implications for the study of Spanish art, which has tended to lag behind in this regard, and similar studies on other Sevillian artists—Francisco Zurbarán, Alonso Cano, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo—would be a welcome addition to the history of early modern Spanish painting. In short, this is an important contribution to the literature on one of the foundational figures of Spanish art, highly recommended to students and scholars alike.”

“The strength of Tiffany’s study is the wealth of contextual detail provided for the four genres of painting she examines. Her book offers a valuable survey of the social, intellectual and spiritual history of Seville, with a marked focus on the latter.”

Tanya J. Tiffany is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Velázquez in Pacheco’s “Gilded Cage”

1 Devotion and Desire: The Immaculate Conception and Saint John

2 Portraiture and the “Virile Woman”: Madre Jerónima de la Fuente

3 A Bodegón and a Collector: The Waterseller of Seville

4 African Slaves and Christian Salvation: The Supper at Emmaus

5 The Lure of the Court

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction:

Velázquez in Pacheco’s “Gilded Cage”

Diego Velázquez’s Adoration of the Magi (fig. 1) encapsulates both the allure and the elusiveness of the artist’s early works. Velázquez painted the Adoration in 1619, when he was a twenty-year-old artist embarking upon his career in Seville. In the Adoration, the holy family, the three magi, and a member of the magi’s entourage appear beneath an archway in a dusky landscape. (The paint has darkened over time, making the background difficult to see.) The figures are rendered with strong colors and intense contrasts of light and shade, which emphasize the three-dimensionality of their forms. Mary is presented as a beautiful young woman clad in rose and blue, her voluminous drapery falling in angular folds across her body. On her lap sits the Christ Child: the focal point of the composition and the center of illumination. Wrapped in swaddling clothes, the child is plump and rosy cheeked, and he looks with wide eyes at the young magus before him. In turn, the magus genuflects as he proffers his gift, a shining chalice painted with brilliant flashes of illumination. Behind him, the elderly magus is shown in profile, the rough texture of his weathered skin painted with thick brushstrokes heavily laden with impasto. Above them stands the third, middle-aged magus: a black African. He is dressed more sumptuously than any other figure in the composition, with a dangling red-and-gold earring, a long crimson mantle, and a white lace collar. The brightness of his collar draws attention to his face, itself rendered with intricate brushwork, detailing the crease in his brow and the bags beneath his eyes. He is the only figure who looks out of the painting, and his intense gaze helps to draw the beholder into the composition.

The Adoration represented a new approach to painting in early seventeenth-century Seville. For Velázquez’s contemporaries, the artist’s youthful works exemplified “the true imitation of nature.” According to early modern theorists, this “true imitation” referred to an ability to paint works of art that displayed not only verisimilitude but the illusion of material reality itself. Those same theorists, however, would also have understood that Velázquez’s paintings, although firmly grounded in nature, were not literal transcriptions of visible reality. Like Christian paintings by nearly all seventeenth-century artists, Velázquez’s Adoration represented a synthesis of myriad visual sources, an awareness of religious doctrine, and a knowledge of prevailing standards of decorum. Yet Velázquez contended with these considerations in new ways. In the Adoration, he affirmed the veracity of the biblical story through his “true imitation of nature,” as exemplified by the sculptural presence of the figures, the imperfections of their features, and the close attention to still-life elements such as the spiny bush in the foreground—itself a reference to the crown of thorns.

The Adoration epitomizes the interplay between extraordinary innovation and pictorial convention in Velázquez’s early works. Velázquez’s ability to blend novelty and tradition was rooted in, if not reducible to, his artistic training and early career in Seville. During his youth, Velázquez apprenticed with the erudite artist and theorist Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644). In Pacheco’s workshop, he learned to use his study of nature in capturing the power of sacred histories and in rendering the likenesses of illustrious contemporaries. As a young artist, Velázquez adopted and synthesized different genres of painting, combining exalted biblical images with lowly kitchen scenes and representing Christ and the saints in concert with the kitchen servants and African slaves who worked in Seville. Velázquez thus abandoned the style and sometimes even subject matter embraced by most Sevillian artists, including Pacheco himself. In his early works, however, he also demonstrated a close critical engagement with the artistic practices, religious faith, and social mores of his native Seville.

The Culture of Velázquez’s Seville

When Velázquez was born in 1599, Seville was the most culturally vibrant city in Golden Age Spain (fig. 2). During the artist’s youth, it was the largest metropolis in Spain and among the largest in Europe, boasting a population as high as 130,000 or 140,000—one comparable to those of Venice and Amsterdam and not far behind those of London and Paris. For contemporaries, Seville remained far more urbane than Madrid, a small town that had become the Spanish capital only in 1561. Among other important cultural figures, two of the greatest writers of the day, Lope de Vega and Miguel de Cervantes, lived for extended periods in Seville.

The particular importance of Seville was predicated upon its status as the center of trade between the Iberian Peninsula and the vast reaches of the Spanish empire. From 1503 until 1717, Seville served as the main Spanish port to the Americas and as the seat of the Casa de la Contratación de las Indias (House of Trade with the Indies), the institution responsible for regulating commerce with the New World. As a crossroads of international trade, the city enjoyed spectacular wealth—enough so that one early modern writer claimed that its very streets could have been paved with the gold and other precious metals brought there from the Americas. Seville’s prosperity also contributed to its thriving artistic and intellectual life. Merchants from northern Europe and Italy flooded the city, bringing with them foreign paintings, prints, sculptures, and books. In the sixteenth century, artists such as the Fleming Pedro de Campaña (1503–1580) and the Italian Pietro Torrigiano (1472–1528, the sculptor who broke Michelangelo’s nose) imported new artistic styles to Seville. At the same time, artists produced images for the scores of monasteries and convents built during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and local merchants and aristocrats commissioned works of art to decorate their homes. During Velázquez’s youth, the prominent Sevillian nobleman the Duke of Alcalá (one of the artist’s early patrons) assembled one of the finest private art collections in Spain: one containing ancient sculptures, works by Italian and Flemish Renaissance masters, as well as paintings by Sevillian artists.

For all its wealth, however, Velázquez’s Seville was also riddled with social problems. As in other prosperous early modern cities, the wealthy Sevillian minority lived side by side with throngs of destitute laborers, servants, and beggars. In keeping with its role as a port to the Americas, Seville was a hub for the transatlantic slave trade. Slave ships headed for the colonies regularly stopped there, and Africans on board were bought and sold by local Spaniards. By the late sixteenth century, the majority of Sevillian upper- and middle-class households—including that of Velázquez’s father—owned slaves of sub-Saharan African ancestry. A number of civic and ecclesiastical authorities feared slave uprisings, associating all “blacks” with a “natural inclination to public crimes.” This was a point of contention, however, and other Church officials argued that Christian salvation could be attained by Africans and Europeans alike.

In Velázquez’s day, historians and religious thinkers in Seville, like those elsewhere in Spain, were also contending with their city’s complicated past. Seville had lived under Muslim rule from 712 until 1248, and it had been home to Jews and Muslims until 1492, when members of those communities were forced either to convert to Christianity or face exile from Spain. When Velázquez was ten years old, the Spanish Crown initiated its mass expulsion of the remaining moriscos (people of Muslim descent), an event that the artist would later commemorate in a painting (now lost) for King Philip IV. Sevillian men of letters responded to Spain’s Jewish and Muslim legacy in part by rewriting its history. Pacheco’s friends, including the humanist Rodrigo Caro and the cleric Juan de Fonseca y Figueroa (one of Velázquez’s patrons), thus embraced contemporary discoveries that supposedly demonstrated the acceptance of Christianity by Spaniards during apostolic times. Their efforts paralleled those of Seville’s powerful archbishop, Pedro de Castro y Quiñones, who ardently defended the authenticity of a group of purportedly ancient relics found near Granada. (The findings championed by these men were soon shown to be forgeries.) Significantly, even some of those engaged in revising Spanish history had roots in Spain’s non-Christian heritage. Like many members of Seville’s upper and middle classes, Fonseca himself was of converso (converted Jewish) ancestry, and his family had spent more than a century trying to remove the evidence of this “stain” from its lineage.

In their concern with Spain’s religious history, seventeenth-century Sevillians also upheld the tenets of the Catholic Reformation. The bishops at the Council of Trent (1545–63) placed particular emphasis upon reviving and maintaining the traditions of the early Church, among them the use of sacred images in instruction and devotion. Consistent with their focus on ancient Christian traditions, the Tridentine bishops stressed the importance of adhering to what they perceived as the veracity of scripture and other canonical texts. In order to fill the gaps left by those accounts, theologians, antiquarians, and artists began to investigate the history of the early Church. Catholic painters were now compelled to represent images of Christ and the saints in strict accordance with textual and pictorial evidence that demonstrated the historical “truth” of the events depicted. Pacheco and his associates ardently embraced this challenge. In a well-known example, Pacheco and his friend Francisco de Rioja, the renowned poet and priest, sought to ascertain the precise manner of Christ’s Crucifixion. Through a careful study of ancient texts and images, they discovered that Christ would have been crucified with four nails rather than the three nails usually depicted by artists. Pacheco therefore began representing the Crucifixion with four nails (fig. 3), “conforming in everything,” as Rioja stated, “to what is said by the ancient writers.” As Jonathan Brown has shown, Sevillian painters followed this practice for decades to come. Velázquez himself adopted Pacheco’s iconography in his emotive Christ on the Cross (fig. 4), painted nearly a decade after he left Seville.

It was within this complex framework of Golden Age Seville that Velázquez was raised. On June 6, 1599, he was baptized in the Sevillian parish church of San Pedro, the first of eight children born to Juan Rodríguez de Silva and Gerónima Velázquez. The artist’s maternal grandfather, Juan Velázquez Moreno, was a stocking maker and merchant who sold goods to the Americas. In 1596, Juan Velázquez spent time in debtor’s prison, but that same year he also offered a large dowry for the marriage of his daughter, Gerónima. On the paternal side of the family, Velázquez’s grandparents are thought to have hailed from Portugal, but little about them is known. The artist’s father, Juan Rodríguez, held the post of chief testamentary notary for Seville’s cathedral chapter, which was a lucrative position that required a primary education and held some measure of prestige.

Despite his middle-class background, Velázquez fashioned himself as a gentleman and claimed noble parentage later in life. Noble ancestry was requisite for winning an honor pursued by Velázquez from at least the 1630s: admission to the exclusive military Order of Santiago, which conferred knighthoods upon its members. Those seeking admission needed to be of noble blood and of exclusively “old Christian” ancestry. They were also required to prove that neither they nor their parents or grandparents had “practiced . . . manual or base occupations,” including those of “silversmith or painter, . . . embroiderer, stonecutter.” As Brown has shown, Velázquez sought throughout his career to transcend his humble origins and at the same time demonstrate that painting was not a “base,” but rather a noble, profession. The artist finally succeeded in 1659, a year before his death, when he was awarded the knighthood that he so ardently desired.

Given the available information on Velázquez’s family and on the circumstances of his admission to Santiago, it has been argued that the artist himself was of converso lineage. The evidence for this is intriguing, if circumstantial; it is perhaps suggested by the occupations of Velázquez’s father (a notary) and maternal grandfather (a merchant), by the Portuguese origins of his paternal grandparents, and by the artist’s own attempt to obstruct the Order of Santiago’s investigation of his Portuguese relatives. Yet it is important not to exaggerate the significance of Velázquez’s religious and ethnic ancestry. Whatever their background, the members of Velázquez’s family—like most seventeenth-century Spanish conversos—were fully integrated into Catholic culture. This is clearly demonstrated by the careers of Velázquez and his father. During his years in Seville, Velázquez worked largely as a painter of religious images. Throughout his own life, Juan Rodríguez de Silva moved up the hierarchy of functionaries employed by the Church, and he was eventually appointed to the coveted position of secretary to Seville’s ecclesiastical judge.

Velázquez and the “Gilded Cage”

Despite the modest social status of his family, the young Velázquez’s association with Pacheco helped him to gain a privileged place in Sevillian society. By all accounts, Pacheco’s studio represented a rarefied artistic and cultural milieu. In 1647, three years after Pacheco died, his friend Rodrigo Caro famously emphasized the role played by Pacheco in Sevillian intellectual life. Caro described Pacheco as “a celebrated painter in this city, whose studio was a regular academy of the most cultured minds [ingenios] of Seville and elsewhere.”

Caro’s remark was later adopted in the first published biography of Velázquez, which was included in the volume of artists’ lives in El museo pictórico, y escala óptica (1715–24), by the court painter and native Andalusian Antonio Palomino. Borrowing from Caro, Palomino described Pacheco’s studio as “a gilded cage of art, academy, and school of the best minds of Seville.” In this context, a “gilded cage” is analogous to an ivory tower: a place where intellectuals devote themselves fully to their studies. Palomino also contended that, while under Pacheco’s tutelage, Velázquez assiduously studied the theory and practice of painting by consulting the works of “various authors” who wrote “on the elegant precepts of art” and by engaging in the “continual exercise of drawing [dibujo], the fundamental element of painting and the principal gateway to art.” (For contemporaries, the term dibujo was roughly equivalent to the Italian disegno, referring both to the practice of drawing and to its intellectual underpinnings.) The remarks included in Palomino’s life of Velázquez are important both for their biographical data and for the insight they provide into the reception of Velázquez’s art in the decades following his death. As scholars have long emphasized, Palomino’s account is also valuable because it relies heavily on a lost biography of Velázquez written by the artist’s own pupil, Juan de Alfaro (1643–1680). Finally, Palomino provides vivid descriptions of several of Velázquez’s early works and helps to locate them within the framework of Sevillian painting.

In a groundbreaking study published in 1978, Jonathan Brown demonstrated that Pacheco’s studio was not a formal academy but rather a meeting place for a group of friends: “a casual but cohesive association of poets, scholars, and painters.” Throughout this book, I use the term “Pacheco’s circle” to emphasize the loose connections that united this erudite group of men. During Velázquez’s youth, no official academies of art as yet existed in Spain, despite several attempts to found one in early seventeenth-century Madrid. The term “academy” (academia) as employed by Caro and Palomino must therefore be understood in its broader sense, meaning a place where painters studied artistic theory and practice and “where men of distinguished minds [came] together to discourse.” As Brown has emphasized, the notion of friendship was particularly important to Pacheco’s associates, who referred to one another as amigos, buenos amigos (good friends), and doctos amigos (learned friends) and relied on each other for intellectual and artistic collaboration.

More recently, scholars have expanded the portrait of Pacheco’s circle and of Velázquez’s place within it. Two exhibitions of Velázquez’s Sevillian paintings (held in 1995 and 1999) have provided rare opportunities for comparing works by the young artist to those by Pacheco and other Sevillians. The catalogues accompanying the exhibitions have also presented new perspectives on Velázquez’s intellectual formation and his engagement with the traditions of Sevillian painting. In a monographic study of the young Velázquez, Luis Méndez Rodríguez has brought to light a wealth of documentary evidence on the artist’s early life, revealing new information about his finances and showing that he took on an apprentice—a certain Diego Melgar—in 1620. Méndez Rodríguez has also demonstrated the lifelong ties that developed between Velázquez’s father and Pacheco; throughout the years, the two men assisted each other in matters of business, and it was Juan Rodríguez de Silva who arranged for Pacheco’s burial in 1644. Jeremy Roe has offered important insights into Velázquez’s Sevillian period by examining the writings of Pacheco’s learned friends. Specifically, he has illuminated little-known texts by Francisco de Rioja, Juan de Jáuregui, and Juan de Fonseca, Sevillians who would also assist Velázquez’s early career in Madrid. In addition, Vicente Lleó Cañal and others have demonstrated that Pacheco’s circle included not only poets and theologians but also cosmographers involved in astronomy and mapmaking at the Casa de la Contratación.

Although this scholarship has proved fundamental in elucidating the milieu in which Velázquez was trained, discussions of cultural context have often taken precedence over analyses of the artist’s paintings themselves. In this study, I therefore seek to bring an investigation of the cultural and social frameworks of Velázquez’s career to bear upon a careful consideration of specific works of art. By placing renewed emphasis on questions of imagery and style, this book explores the ways in which Velázquez’s paintings developed in relation to the vibrant culture of seventeenth-century Seville.

Defining Velázquez’s Sevillian Oeuvre

A major challenge to studying Velázquez’s early paintings, however, is presented by the question of precisely which works can be attributed to the artist. This issue has recently come to the fore with regard to three images ascribed to the young Velázquez by various scholars: an Education of the Virgin (fig. 5) at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, a Saint John the Baptist at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 6), and an Immaculate Conception (fig. 7) at the Centro Velázquez in Seville. John Marciari first published the Education of the Virgin in 2010, hailing it as a major addition to Velázquez’s oeuvre, but the attribution has been contested by Jonathan Brown, who has disparaged the painting’s “poor quality” and asserted that it “cannot possibly be the work of the master.” Art historians also remain divided on the authorship of Saint John the Baptist, which has been given to Velázquez by specialists including Javier Portús and Peter Cherry but is simply deemed a product of the school of Seville by the Art Institute. In contrast, a majority of scholars have agreed on attributing the Seville Immaculate Conception to Velázquez, with a notable dissension by Alfonso Pérez Sánchez, who has ascribed the painting to Velázquez’s friend and Pacheco’s sometime pupil Alonso Cano.

The attribution of paintings is a notoriously subjective undertaking, and scholars will doubtless continue to debate the authorship of these three works. To my mind, however, all were painted by Velázquez’s Sevillian contemporaries and followers, rather than by the artist himself. In terms of style, these paintings differ in important ways from Velázquez’s early production, even as they recall his youthful imitation of nature, strong chiaroscuro, and use of particular iconographical motifs. Unlike the exquisitely composed and technically virtuosic paintings by the young Velázquez, the Education of the Virgin is imbalanced in its composition and almost sloppy in its depiction of heads and hands. In contrast to Velázquez’s careful rendering of textures and sensitive portrayal of faces, the still-life elements in Saint John are painted with haphazard brushstrokes, and the Baptist himself is an expressionless man with an unfocused outward stare. Regarding the Immaculate Conception, the composition represents a clear borrowing from Velázquez’s autograph version of the theme (fig. 10), but its depiction of the Virgin suggests the hand of another artist, perhaps indeed Cano. Whereas Velázquez’s Mary is a slim girl with a demure countenance and a delicately pretty face, her counterpart in the Seville painting is a bulky figure with bland, ill-defined features.

Although probably not painted by Velázquez, works such as the Education of the Virgin, Saint John the Baptist, and the Seville Immaculate Conception are relevant in elucidating the broader artistic context in which he operated. Surely painted by artists active in Seville during or not long after Velázquez’s time there, these images are useful in shaping an understanding of the seventeenth-century painters who imitated the young artist. At various points throughout this book, I address the question—one still little understood—of Velázquez’s early followers and copyists. Although I focus on works that are universally ascribed to Velázquez, I have considered questions of attribution when exploring broader issues regarding the artist’s Sevillian production and its impact on contemporaries.

Unanswered Questions

For all the advances in scholarship, then, Velázquez’s youth in Seville remains the least understood period of his long career. Beginning at least with Palomino, critics and scholars have acknowledged that Pacheco and his friends played important roles in Velázquez’s intellectual formation. But what those roles were remains unknown. This problem is especially difficult because Velázquez developed a pictorial style bearing little resemblance to Pacheco’s (see especially figs. 3, 12). Modern art historians have generally agreed with Palomino, who contended that Velázquez admired Pacheco’s “erudition” but rejected his “tepid” manner of painting. In general terms, Palomino’s assertion is surely correct; Velázquez did abandon his teacher’s artistic style, even as he came to personify the cultured artist advocated by Pacheco.

Yet Palomino’s statement leaves a number of important questions unanswered. To what extent did Velázquez share the particular theoretical concerns of Pacheco and his friends? In what ways did Velázquez engage with their works? Is this engagement evident in his paintings? Can the writings of Pacheco’s associates shed light on the imagery and style of Velázquez’s compositions? Do the young artist’s paintings conform to the doctrinaire, post-Tridentine precepts so emphasized by Pacheco and his associates? If so, why do they bear so little resemblance to the works of other contemporary Sevillian artists?

Master and Pupil

In order to begin answering these questions, it is important to understand the particular relationship between Velázquez and Pacheco. Velázquez entered Pacheco’s studio in 1611 at the age of twelve, a fairly standard age for artists to begin the six-year training stipulated (but not always enforced) by the Sevillian painter’s guild. Like many apprentices, Velázquez lived in his teacher’s house for the duration of his training, and Pacheco assumed responsibility for providing his charge with “food, drink, clothing, and shoes.” Although little is known about the division of labor in Spanish workshops, Velázquez probably assumed the same responsibilities as apprentices elsewhere in Europe, who began by mastering their skills as draftsmen and eventually collaborated on studio commissions, painting secondary elements such as landscapes and still-life objects.

Velázquez’s formation before 1611, however, remains a matter of conjecture. In his Museo pictórico, Palomino contends that Velázquez had studied letters (buenas letras) before beginning his apprenticeship, and scholars have plausibly suggested that he attended one of the local Jesuit schools, which dominated primary education in Catholic Europe. If so, the young Velázquez would have learned to read and write in Spanish and rudimentary Latin, acquiring an education comparable to that of his father. Adding to the mystery of Velázquez’s earliest years, however, scholars have also speculated that he began his artistic training before entering Pacheco’s studio. In fact, the contract of 1611 indicates that Velázquez’s apprenticeship was already under way, having begun “on the first of December of this past year of 1610.” This date is significant because around that time Pacheco embarked on one of the few extended journeys of his life, traveling northward to Madrid, El Escorial, and Toledo, where he famously met El Greco. Perhaps providing a clue to Velázquez’s activities in the intervening months, Palomino argues that the young painter spent a short time under the tutelage of the apparently irascible Sevillian artist Francisco de Herrera before fleeing to Pacheco’s studio. In his writings, Pacheco himself may allude to Herrera when he decries the “temerity” of a certain “someone who has sought to claim this glory [i.e., of having trained Velázquez] and thus rob me of my laurels in my final years.”

Whatever Velázquez’s previous education and artistic training, it is clear that Pacheco played the most significant role in the young painter’s professional development. Evidence suggests that Pacheco was a dedicated and effective teacher. In the prologue to his monumental treatise, the Arte de la pintura (1649), Pacheco emphasizes his “desire to teach,” and throughout the text (especially when discussing religious iconography) he addresses the needs of painters still learning their art. He also devotes an entire section of the Arte to the training of “three levels of painters,” in which he describes a method of instruction meant to guide the most talented students from the rank of “beginners,” who simply copy various models, to that of “perfect” painters, capable of inventing their own compositions. Perhaps significantly, Pacheco also helped to train other well-known artists. For example, the painter, sculptor, and architect Alonso Cano spent time in Pacheco’s studio, where he would have supplemented the education he received from his father, who specialized in designing altarpieces. According to Palomino, the ill-tempered Francisco de Herrera similarly apprenticed under Pacheco. Like Cano, Herrera probably studied with his father (an engraver and manuscript illuminator), but he may have learned to paint large-scale subjects in Pacheco’s workshop. Finally, Pacheco was the teacher of Francisco López Caro. Palomino describes López Caro as a gifted portraitist, but the artist’s work is known today only through a signed bodegón once attributed to Velázquez. Velázquez’s own apprenticeship coincided with those of Cano and López Caro, and he apparently developed long-standing relationships with each of them, who both testified in favor of his admission to the Order of Santiago.

Although Pacheco helped to train various painters, the Arte reveals that Velázquez was his most prized apprentice. Building on a long tradition of praising the teachers of famous men, Pacheco compares his relationship with Velázquez to those of various important masters and the pupils who surpassed them. He explains, “I do not consider it discrediting when the student surpasses the master . . . Leonardo da Vinci did not lose in having Raphael for a disciple, nor Giorgione da Castelfranco in having Titian, nor Plato in having Aristotle.” For those familiar with Pacheco’s paintings, it may seem presumptuous for the artist to compare himself to Leonardo (who was not, in fact, Raphael’s teacher) and Giorgione. But this statement also sheds light on Pacheco’s conception of what constitutes a great painter. With these comments, Pacheco likens himself and Velázquez not only to celebrated artists but also to famous philosophers. In so doing, he suggests that he and his student are consummate practitioners of painting as well as men of formidable intellect. As indicated by these comparisons, Pacheco’s treatise asserts that the best artists are those who combine practical skills with theoretical learning.

After becoming a master painter, Velázquez remained intimately connected to Pacheco through familial and professional bonds. In 1618, Velázquez married Pacheco’s daughter, Juana. Pacheco contends that he encouraged the match because he had lofty expectations for his former pupil. He explains that after the conclusion of Velázquez’s “education and instruction I married him to my daughter because of his virtue, purity [of blood], and good qualities, and because of the promise of his natural and great ingenio.” (For Velázquez’s contemporaries, the term ingenio referred to a “natural force of the intellect” needed for the creation and understanding of the various “subtleties” and “inventions” found in works of art, literature, and other fields.) It is possible that this emphasis on “purity” represented an effort to dispel questions about Velázquez’s ancestry. In any case, Velázquez’s marriage followed a practice common in Seville and throughout Europe, in which such alliances allowed young artists to benefit from the patronage networks established by their masters.

From his earliest years as an artist, Velázquez profited from his teacher’s social connections, painting works for the Duke of Alcalá, Juan de Fonseca y Figueroa, and for religious institutions whose members formed part of Pacheco’s circle. Indeed, Pacheco’s friends would continue to support Velázquez’s career even after his move to court in 1623. Pacheco himself lived in Madrid with Velázquez and his wife from 1624 until 1626, when Velázquez tried in vain to secure him a position as royal painter. An examination of the Arte also indicates that the two men remained in close contact until Pacheco’s death, in 1644. In 1643—five years after the Arte was completed—Pacheco added a marginal note to his finished treatise, boasting of his son-in-law’s new status as the king’s gentleman of the chamber (ayuda de cámara). Two years later, Pacheco’s widow moved to Madrid and lived with her daughter and son-in-law until she died, in 1647.

The Arte de la pintura and Pacheco’s Circle

Given the relationship between master and pupil, it is hardly surprising that writings by Pacheco provide the fullest account of Velázquez’s place in Seville. The Arte de la pintura is especially relevant here because Pacheco worked on the text throughout Velázquez’s youth. He began writing the treatise at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and he published several fragments in the late 1610s and early 1620s, finally completing the text in 1638. Pacheco’s treatise is important not only for the pieces of information it provides on Velázquez but also for the crucial insight it offers into the critical context in which his most promising student developed his art.

The Arte indicates the broad scope of artistic discourse available to the young Velázquez. Modeled in part on late sixteenth-century Italian treatises, the Arte is divided into three discursive books dealing respectively with the history, theory, and practice of painting. The final book also includes a long appendix on religious iconography, the “Adiciones a algunas imágines” (Additions to Some Images). In his superb critical edition of the text, Bonaventura Bassegoda has highlighted the wealth of source material employed by Pacheco, who was conversant with most of the Italian and northern European artistic treatises published before 1638. Pacheco’s main foreign sources were sixteenth-century Italian texts, works ranging from Giorgio Vasari’s Vite (1568 ed.) to Ludovico Dolce’s Aretino (1557) and Giovanni Lomazzo’s Trattato della pittura (1584). In his consideration of sacred paintings, Pacheco expands upon the works of Catholic reformers such as Johannes Molanus and Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, both of whose works emphasize the function of religious images. He also frequently cites the authority of the Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia (1595) by Gerónimo Nadal, and he admonishes artists to consult the engravings accompanying the text—advice that was taken by the young Velázquez.

The Arte furthermore provides a vivid picture of intellectual life in Velázquez’s Seville. Brown has shown that the treatise not only represents an expansion of Italian artistic theory; it is also a direct product of the exchanges conducted by members of Pacheco’s circle. In the Arte, Pacheco continually alludes to his associates and their writings, and he often synthesizes the scholarship of these local experts with that of artistic theorists from Italy and elsewhere. For example, he emphasizes his close consultation with the theologian Luis del Alcázar (1554–1613) and other Sevillian Jesuits, who shared his belief in the importance of sacred images. He also routinely invokes the learning of his personal friend Pablo de Céspedes (before 1548–1608), a painter and cathedral prebendary from nearby Córdoba. Céspedes embodied Pacheco’s archetype of the “erudite painter,” having trained as an artist in Rome and studied ancient languages at the prestigious University of Alcalá de Henares. In addition, Pacheco makes significant use of the writings of the Sevillian poet and painter Juan de Jáuregui (1583–1641), who likewise studied in Rome and who read and critiqued the Arte as Pacheco prepared it for publication. The local authority most frequently cited in the Arte, however, is the poet and cleric Francisco de Rioja (1583–1659). We have already seen that Rioja helped Pacheco to determine the number of nails used in the Crucifixion. He also testified to the historical accuracy of the inscription on Pacheco’s Christ on the Cross (fig. 3), an issue that sparked an intense debate among Sevillian men of letters. When the Duke of Alcalá argued that Pacheco’s inscription was a “novelty”—an anachronism not grounded in Christian history—it was Rioja who publicly came to the artist’s defense. As made clear by the Arte, Pacheco’s circle was held together by this strong sense of friendship and intellectual collaboration.

In addition to the Arte, other writings by Pacheco and his associates help to round out the picture of the environment in which Velázquez was trained. As Marta Cacho Casal has shown, Pacheco’s Libro de descripción de verdaderos retratos de ilustres y memorables varones (Book Containing Descriptions of True Portraits of Illustrious and Memorable Men; probably begun before 1599) is an important, if unfinished, treatise containing biographies and drawings of contemporary luminaries, many of them Pacheco’s personal friends. The Libro de Retratos (as the text is generally known) is especially valuable because it provides rare insight into a number of the men, many of them largely forgotten to history, who played crucial roles in shaping discourse as conducted within Pacheco’s circle. Pacheco also compiled his own writings and those of his associates in several manuscript volumes containing letters, poems, short treatises, and even riddles. The manuscripts include texts on a variety of topics: among them a “Discourse in Defense of Priests with Beards” by Rioja, a dialogue on “the Immaculate Conception of Our Lady” by Pacheco, and a witty epithalamium (a nuptial poem) by Baltasar de Cepeda written in honor of Velázquez’s wedding, an event attended by Rioja and other important local figures.

An examination of Pacheco’s circle elucidates the cultural, intellectual, and religious contexts of Velázquez’s formation. As a result of his training in Seville, Velázquez became, in many ways, the paradigmatically learned painter championed by his teacher. According to Palomino, the young artist sought to “feed his mind with every kind of learning,” studying treatises from Vitruvius on architecture to Federico Zuccaro on artistic theory. Whether Velázquez actually consulted such works has been a point of contention among scholars, who have often suggested that the young artist’s brilliant practice seems at odds with dry academic precepts. In this book, I approach the problem from a different perspective. I argue that what is important is the young Velázquez’s ability to bring his practical talents to bear on his awareness of the issues animating the world of letters. During his youth, Velázquez became intimately familiar with the intellectual discourse conducted in Pacheco’s studio. By the time he died, in 1660, he possessed a library of 156 books: an extraordinary number for an artist of the time. At that point he owned most of the works that, according to Palomino, he had read as a young man. The majority of the texts in the inventory are closely related to Velázquez’s artistic production. He owned works mainly on optics, perspective, and geometry, but he also possessed treatises on history, mythology, and religion. Of course, we cannot know whether Velázquez read every book in his collection, but the library serves as important evidence of his intellectual predilections. As suggested by the evidence of the inventory and by the testimony of his paintings, Velázquez aspired throughout his life to the union of theory and practice advocated in Pacheco’s studio.

Yet despite his close relationship with Pacheco, Velázquez reinvented his teacher’s definition of a great painter. Whereas Pacheco revealed his learning through his literary works, Velázquez demonstrated a keen pictorial intelligence. Scholars have long acknowledged the role played by this quality in the dazzling technique and subtle invention of late works such as the Fable of Arachne (fig. 8) and Las meninas (fig. 9). Throughout this book, I argue that Velázquez’s visual intelligence is equally apparent in his Sevillian paintings. The young Velázquez used his intense study of nature in his transformation of various sources, including paintings, sculptures, mass-circulated prints, and other forms of visual culture. He also contended with issues of vital concern to Pacheco and members of his circle. Among other themes, his paintings addressed the nature of artistic creativity, the place of religion in everyday life, the role of women in the Catholic Church, and the incorporation of African slaves into Christianity. A close comparison of Velázquez’s paintings with texts by local men of letters—many of which have never been discussed until now—thus reveals the artist’s engagement with key topics of debate in early seventeenth-century Seville. In his early works, Velázquez explored the themes addressed in Pacheco’s writings, even as he defied many of his master’s artistic precepts.

Perhaps most strikingly, Velázquez departed from Pacheco in his engagement with nature. Although Pacheco advocated the study of nature, he (like most theorists) admonished artists to imitate nature selectively, choosing only “the most beautiful works of God” and painting them in a “lovely manner.” For Pacheco and others, this selective imitation was exemplified by Renaissance masters such as Leonardo, Raphael, and Titian, whose figures were at once “natural” and exquisitely beautiful. The young Velázquez challenged this paradigm. In genre scenes and even in religious works, he departed from Pacheco’s emphasis on representing only “the best . . . and most perfect.” As we have seen, he depicted the magi in the Adoration (fig. 1) as ordinary men with flawed features, which are accentuated by intense contrasts of light and shade. Although Pacheco reserved the highest praise for artists who followed the example of Raphael, he suggested that the realism of Velázquez’s works made even the most storied masterpieces seem merely “painted” by comparison. (I use the term “realism” instead of “naturalism” as a means of distinguishing the plain, sometimes homely types painted by Velázquez from the ideal but “natural” figures painted by Titian and others.) For Pacheco, Velázquez achieved this “true imitation of nature” through his strong chiaroscuro and especially through his practice of painting—rather than simply drawing—from live models. This method of “keeping to nature” was a novelty in Spain, and Pacheco argued that it helped to set Velázquez’s works apart from those of “the rest.”

Even as a youth, Velázquez thus took an experimental approach to his art. He used his realist style in the Adoration and a number of other religious images, in which he gave shape to the truthfulness of sacred histories. The artist thematized his “true imitation of nature” when painting lowly subjects known as bodegones (a term roughly equivalent to “genre scenes”; see figs. 39–40, 44), and he challenged the conventions of sacred imagery by painting “inverted” compositions (figs. 48, 50): bodegones with small religious scenes in the backgrounds. Although some contemporaries disapproved of these innovations, Velázquez’s works were coveted by Seville’s most learned and illustrious collectors.

Velázquez’s Early Paintings

The convergence between Velázquez’s art and Sevillian culture is explored in the five chapters that follow. In each of the first four chapters, I concentrate on an individual painting or pair of paintings, representing every genre in which the young Velázquez worked: sacred imagery, portraiture, bodegones, and “inverted” religious scenes. My concluding chapter moves from Seville to Madrid, examining the relationship between Velázquez’s early works and his triumph as a court artist. By focusing most of the book on specific paintings, I am departing from the standard monographic format, in which Velázquez’s career (or a period thereof) is examined as a whole. Although the monographic approach has proved vital to understanding Velázquez’s development as a painter, I seek to offer the rich contextual interpretations provided by close readings of individual works of art. Insofar as possible, I therefore consider Velázquez’s paintings with regard to their patrons, original locations, and early reception. Throughout, I locate Velázquez’s youthful production within the historical, social, religious, and artistic contexts of seventeenth-century Seville.

Chapter 1 considers the connection between painting and beholder in Velázquez’s early religious images. Specifically, I examine the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception and Vision of Saint John the Evangelist (figs. 10–11) as pendants originally conceived for their audience of friars at the Sevillian Calced Carmelite monastery, El Carmen. The paintings illustrate Sevillian religiosity in the late-1610s, when Church officials and pious citizens staged elaborate festivals demonstrating support for the doctrine proclaiming Mary’s Immaculacy. Velázquez’s Immaculate Conception conforms largely to Pacheco’s prescription for depicting the theme, and both pendants correspond to the iconography of the Carmelite order. Yet Velázquez also transcended contemporary pictorial conventions. By pairing the Immaculate Conception with Saint John, he demonstrated the fundamental importance of the Carmelites, whose ancient founder was the first to witness a vision symbolizing the Virgin Immaculate. As elucidated by the writings of El Carmen’s residents, Velázquez also devised a means of tempering the sexual desire that sometimes accompanied Marian devotion.

Chapter 2 turns to Velázquez’s early engagement with the traditions of portraiture in Seville. In a new interpretation of a well-known image, I examine Velázquez’s constructions of gender and holiness in Madre Jerónima de la Fuente (figs. 25–26), a portrait commemorating a Poor Clare (a Franciscan nun) from Toledo who founded the first convent of nuns in the Philippines. When painting Madre Jerónima, Velázquez followed Pacheco’s example of glorifying his subject by capturing her likeness rather than idealizing her features. In comparing the portrait to seventeenth-century biographies of Jerónima, I argue that Velázquez discovered a way of representing a “virile woman” (mujer varonil)—a woman of extraordinary fortitude—through the figure’s strong outward gaze. He reinforced the portrait’s impact on its audience of Toledan Poor Clares by depicting Jerónima as an exemplar of Franciscan sainthood. The portrait was surely commissioned by one of Jerónima’s male religious superiors, and it allowed Velázquez to establish contacts with patrons outside of Seville. Significantly for the ambitious young artist, the Spanish royal family supported both Jerónima’s mission and the Toledan convent for which the portrait was painted.

In Chapter 3, I examine what is often considered Velázquez’s earliest masterpiece, the Waterseller of Seville (fig. 40). Shedding light on the critical context of Velázquez’s bodegones, I analyze the Waterseller in concert with the artistic precepts of Pacheco and his friends, including the painting’s first owner, Juan de Fonseca y Figueroa. Through a detailed consideration of images and texts, I examine Velázquez’s challenge to the lowly status of bodegones in seventeenth-century artistic discourse. In the painting, the artist vaunted his lowly subject matter, even as he adopted the lofty conventions of poetry through a series of ingenious visual puns. The Waterseller also offers a key opportunity to consider Velázquez’s relationship with Fonseca, who became one of his most crucial supporters at court. I argue that Velázquez developed the imagery of the painting with an eye toward gratifying Fonseca’s artistic tastes and erudite interests. At the same time, he created a composition that encouraged Fonseca to draw visual pleasure, intellectual satisfaction, and perhaps even spiritual comfort from a humble bodegón.

Chapter 4 considers the central role of an African slave in Supper at Emmaus (fig. 48), a painting that combines a bodegón and a religious subject. This chapter provides a framework for examining the intersection of race and religion in seventeenth-century Spanish art. In Supper at Emmaus, Velázquez represented the African woman in the foreground and Christ’s revelation at Emmaus in the background. I argue that Velázquez’s unusual composition gave shape to seventeenth-century debates on the spiritual salvation of African slaves in Seville. Through his use of light and shade, Velázquez created a visual interpretation of discourse on African spiritual “illumination” and developing theories of race. Like contemporary Sevillian preachers, he compared the apparent awakening of an African slave to the sudden realization of Christ’s unbelieving disciples. Treatises by Sevillian clerics also provide insight into the original, elite audience for whom Velázquez surely constructed his African subject. By relating previously unexplored texts to Velázquez’s image, I suggest that the relationship between beholder and subject in Supper at Emmaus reflected the dynamics between male slave owner and female African slave.

My fifth and final chapter provides the first sustained account of Velázquez’s transition from his career in Seville to his position as a court painter. When he visited Madrid in 1622, Velázquez benefited from the patronage of Fonseca and other Sevillians residing at court, who succeeded in making his talents known to the king. Through an examination of writings on courtly comportment, I argue that Velázquez represented himself as an exemplary portraitist, ideally suited to painting Philip IV. This chapter also provides an answer to a question that has long puzzled scholars: why did Velázquez abandon his practice as a painter of bodegones after arriving at court? Pacheco and other theorists argued that artists who specialized in bodegones rarely won the favor of kings, and Velázquez heeded this contention by focusing on portraiture in Madrid. When he was finally invited to paint King Philip IV, Velázquez brilliantly synthesized his skills as a portraitist with his ambitions of becoming a courtier. Employing his realist style, he rendered Philip’s likeness so convincingly that he was deemed the first artist truly to portray the king. Velázquez thus set the stage for a long career in which the craft of painting and the art of courtly self-fashioning would become almost indistinguishable.

Throughout this book, I emphasize the inseparability of the young Velázquez from the visual and intellectual culture of early seventeenth-century Seville. I argue that by expanding on his training in Pacheco’s studio, Velázquez learned to bring his “true imitation of nature” to bear on deceptively simple compositions, in which the illusion of reality engaged the viewer’s eyes while the ingenious imagery stimulated his or her intellect. Raised in a milieu that prized the ingenio of poets and painters, Velázquez also invented new ways of representing well-known themes, personages, and stories: the Virgin’s Immaculate Conception, the likeness of a contemporary nun, and the meaning of Christ’s Supper at Emmaus. It was this synthesis of realism and invention that earned Velázquez the respect of the Sevillian men of letters who so admired his youthful paintings. These early viewers apparently delighted in the elusively magical compositions in which Velázquez often seemed to have re-created reality itself.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.