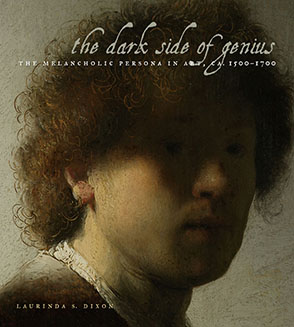

The Dark Side of Genius

The Melancholic Persona in Art, ca. 1500–1700

Laurinda S. Dixon

“Laurinda Dixon brilliantly illuminates melancholy, the dark mental condition, which was both feared and sought by artists and writers in early modern Europe. Her comprehensive history insightfully explores social attitudes about creativity and madness in art, literature, and medicine.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association

The Dark Side of Genius uniquely identifies allusions to melancholia in works of art that have never before been interpreted in this way. It is also the first book to integrate visual imagery, music, and literature within the social contexts inhabited by the melancholic personality. By labeling themselves as melancholic, artists created and defined a new elite identity; their self-worth did not depend on noble blood or material wealth, but rather on talent and intellect. By manipulating stylistic elements and iconography, artists from Dürer to Rembrandt appealed to an early modern audience whose gaze was trained to discern the invisible internal self by means of external appearances and allusions. Today the melancholic persona, crafted in response to the alienating and depersonalizing forces of the modern world, persists as an embodiment of withdrawn, introverted genius.

“Laurinda Dixon brilliantly illuminates melancholy, the dark mental condition, which was both feared and sought by artists and writers in early modern Europe. Her comprehensive history insightfully explores social attitudes about creativity and madness in art, literature, and medicine.”

“The first comprehensive study of melancholia in early modern Europe, The Dark Side of Genius is original and fascinating. Musicologists, gender scholars, religious studies specialists, art historians, and historians of science will benefit greatly from this intriguing and invaluable book. Laurinda Dixon sheds new light on religious melancholia, love melancholia, scholarly melancholy, and artists who are melancholics, and she ends with a discussion of the syndrome's cure. Her book explores many long-neglected texts and images, and it is written clearly, concisely, and in a lively manner. The book, in short, is a pleasure to read.”

“Laurinda Dixon’s carefully developed examination of the various types of melancholia establishes the ways in which visual culture appropriated the discourse on melancholy into a wide range of artistic work. Brilliantly incisive and fully interdisciplinary, this book poses new ways of interpreting artworks across the centuries. Readers will be eternally grateful to Dixon for her mastery of a complex theoretical approach and for making it possible to see thematic relationships in a new way. The book is an absolute triumph, combining the erudition of a deeply engaged scholar with the creative imagination of an artist.”

“Today denoting a temporary sadness or state of pensive reflection, melancholy was traditionally understood as a serious affliction of the intellectually gifted, especially religious contemplatives, scholars, and artists. In her comprehensive and well-documented survey, Laurinda Dixon traces the development of melancholy as a medical concept from its origins in ancient Greece and explores its expression in the visual arts with a wealth of illustrations. Dixon also shows how melancholia became a ‘stylish disease,’ its visual manifestations adopted by frustrated lovers, by Rembrandt and other artists in their self-portraits, and by those who aspired to a comparably privileged status. An epilogue traces the gradual extinction of melancholia as a medical concept in the eighteenth century, and its brief revival by the Romantic artists of the nineteenth. Dixon’s fascinating account of melancholia is a major contribution to our understanding of early modern Western culture.”

“[The Dark Side of Genius] belongs beside such classic studies of melancholy and the artist, as the works by Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art (London: Thomas Nelson, 1964) and Rudolf and Margot Wittkower, Born Under Saturn: The Character and Conduct of Artists (New York: Random House, 1963). In addition, the author contributes to the literature on artistic genius. . . .The publisher has produced a handsome volume that will be welcomed and admired not only by art historians but also by visual culturalists. This ‘interdisciplinary’ study, as the author describes it, will also be of value to historians of music, religion and science.”

“A beautifully illustrated book that goes a long way to proving that iconography is alive and well in the study of Renaissance art history. Dixon deftly traces the visual evolution of the pervasive cultural concept over two millennia through its religious, artistic, philosophical, and scientific manifestations. Her attention to Thomas Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) and its influence throughout three centuries is a most welcome introduction. Her visual examples (both famous and relatively unknown) are expertly chosen and reflect melancholy by way of its humoral and astrological influences. Focusing on the Western male hermit, scholar, and lover, the text aptly brings to light the fundamental oppositional traits of melancholia—hot and cold, active and passive, light and dark, etc.—that course through both the artistic genius and the lonely sufferer who falls under the planetary influence of Saturn. Dixon has done an impressive amount of research, even looking at all the medical dissertations on the pathology of melancholia written throughout Europe over two or three centuries. The book is chock-full of interesting and remedial tidbits, such as what animals (owls, swans, stags, cats, and dogs) were viewed as ‘carriers,’ why tobacco intensified melancholy’s effects, and why white wine (and not red) could be used as an antidote, as well as different herbal remedies, music (especially that of Orpheus’s lyre and David’s harp), God-like thoughts, certain colors and foods, physical exercise outdoors in the sun, and, not least, lovemaking.”

“[The]Dark Side of Genius is essentially an art history, and is lavishly illustrated. . . . This is a coffee-table book and much more: a pleasure to own as a real book rather than as an e-book, as well as excellent in its scholarship and style. It brings us to a better understanding of the notion that, as Laurinda Dixon states in the final sentence, ‘to be accepted as a genius, one must look the part.’ . . . We are not surprised to find that the discourses of melancholy and genius had their own related visual codes in the early modern period, but what Dixon does so well is to bring a new depth and range to existing art-historical studies, the most important of which remains Saturn and Melancholy by Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl (1964).

“. . . If one has an interest in early modern melancholy, one should buy this book, and not just for the illustrations. Dixon sheds new light on both familiar and unfamiliar images and texts, and in doing so has provided a thing of beauty for the modern researcher, unwittingly giving us a new treatment for our own ‘professorial melancholia.’”

“Dixon’s Dark Side of Genius is, without hyperbole, a work of some genius. Full of well-written prose and careful conclusions, the book exists at the intersection of a few different disciplines, among which history of medicine looms large. Scholars of almost any discipline, who have interests in the body, its illnesses, and its composition, will find something here to reward them.”

“It is truly a thought-provoking image, which only serves to entice the reader further into Dixon’s work. The Dark Side of Genius effortlessly transcends disciplinary boundaries, bypassing the long-established ‘isolation’ of disciplines who ‘take little notice of one another’, despite the vast ‘historical and cultural importance of melancholia … across the broad scholarly spectrum’ (p. 4). This approach solidifies the book’s broad applications to a variety of disciplines, upholding the true, ‘universal’ nature of melancholia itself.”

“The blend of medical, literary, and art-historical learning and lore underpinning Dixon’s analysis of this topic is typical of the interdisciplinary erudition demonstrated in this lucid and engaging study.”

Laurinda S. Dixon is Professor of Art History in the Department of Art and Music Histories at Syracuse University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The Problem of Melancholia

1 Saturn’s Privileged Realm: Meaning and Melancholy

2 Privileged Piety: Religious Melancholy

3 Privileged Passion: Love Melancholy

4 Privileged Work: Scholarly Melancholy

5 A Privileged Profession: Artists and Melancholy

6 Wine, Women, and Song: Melancholy Mediated

Epilogue: Melancholia Denied and Revived

Appendix: Medical Dissertations on Melancholia and Related Subjects, ca. 1590–1750

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction:

The Problem of Melancholia

Albrecht Dürer’s cryptic Melencolia I (1514) is considered a major monument of art history, and rightly so. It is difficult to summon new superlatives to describe the visual impact of this engraving, which marks the pinnacle of Dürer’s artistic output. Its virtuosic chiaroscuro light effects and dazzling intaglio technique create a flawless illusion of reality, meticulously defining the textures of fabric, flesh, and fur. But it is the print’s elusive subject that fascinates us even more than its superb technical qualities. What does it mean? Dürer kindly supplied a title in the words Melencolia I, splayed across the wings of a flying bat in the upper left corner. This is a good beginning, but how do the other figures and objects fit in? The pictorial space is dominated by an angelic muse, seated on the ground in a pose that suggests weariness or dejection—perhaps frustration. With darkly shaded eyes and knitted brow, she gazes upward in seeming consternation, a pair of dividers poised in her right hand and a latched book in her lap. As if to mock her mental and physical inertia, an industrious putto, seated precariously atop a millstone, works busily at something—we know not what. An emaciated sleeping dog shares the rest of the pictorial space with several other objects, many of which have associations with time and measure. A blazing comet, bound by the overarching curve of a rainbow, streaks across the sky above, providing an element of celestial drama to the scene.

The meaning of Melencolia I must once have been accessible to its intended audience, as Dürer chose to disperse his composition to a broad public via the print medium. But the specific visual vocabulary that once supplied meaning and continuity to the engraving is lost to us today. Its cryptic imagery, with references to philosophy, geometry, astrology, alchemy, and medicine, has inspired diverse and sometimes fantastic explanations, though most scholars generally agree that the engraving was intended both as a personal statement and as a manifesto in support of the Renaissance phenomenon of the “artist as genius.” As such, Melencolia I marks a turning point in history, when the conventional medieval perception of art as a predominantly manual craft was augmented by the belief that artists possessed unique intellectual and creative gifts.

Melancholia: Meaning and Context

Today, the word “melancholia” (or “melencolia,” as Dürer spelled it) describes a psychological condition akin to depression or bipolar disorder. But melancholia was once defined as a corporeal illness, as widely feared as cancer and heart disease are today. Pre-Enlightenment authorities blamed it for a host of unsavory things, including mental depression, cholera, syphilis, witchcraft, and even murder. Criminals and sociopaths commonly succumbed, owing to the influence of the planet Saturn, melancholia’s controlling entity. But despite its negative connotations, melancholia was also valued for its beneficial qualities. Since the time of Aristotle, the condition, thought to be caused by an accumulation of black bile in the body, was also believed to afflict aristocrats, intellectuals, hermit-saints, and creative men of genius. Thus references to melancholia in art throughout history communicate a curious combination of apprehension and reverence. Although the philosophical underpinnings alluded to in Dürer’s engraving are no longer relevant, melancholia’s early modern associations remain in our modern consciousness. Who has not described him- or herself as “down in the dumps,” “in a bad humor,” “feeling blue,” or even “madly in love”? The origins of these metaphors, and others, are lost to contemporary wisdom, but all stem from an acute observation of physical and mental symptoms that marked the beginning of clinical medicine, and they continue to live in the modern field of cognitive science.

Before the so-called scientific revolution, which witnessed the overthrow of classical Greek medical paradigms, mind and body were considered inseparable. The modern distinction between mental and physical illnesses was anticipated in the seventeenth century by René Descartes, who emphasized the distinct natures of the “mechanical” body and the psychic soul. However, not until the late nineteenth century, with the development of psychoanalysis, was the separation of mind and body fully realized. Before this time, the physical complaints associated with the early modern phenomenon of melancholia—pallor, abdominal troubles, and heart palpitations—could cause or be caused by certain psychological symptoms—exhaustion, depression, and mood swings—that remain in the modern definition of the term. The concept of “personality,” as we now call it, was tied to a visual and descriptive way of thinking that associated the state of one’s inner soul inexorably with the outward appearance of the body. Melancholia, in its physical and psychological aspects, was a condition thought to define what we today might refer to as the “creative personality.” Associated with men of genius since ancient times, it could be instigated by any number of circumstances, ranging from accident of birth to one’s choice of friends. Over time, several cultural contexts contributed to melancholia’s link with the qualities of piety, intellect, nobility, and creativity. By the seventeenth century melancholia had become a means of self-valorization, and its travails were part of the cultural vocabulary given form internationally in all branches of the creative arts.

Early modern ideas about melancholia, whether expressed in the arts, religion, philosophy, or medicine, were strongly influenced by ancient and medieval elements. Quite unlike modern science, which changes and evolves minute to minute with every new discovery, pre-Enlightenment theorists believed that the older the idea, the closer it was to the truth. They were careful to bolster their theories with quotations from the ancients, which lent their own ideas credence. Ancient wisdom and Christian faith were only gradually replaced by empirical knowledge, gleaned from experimentation and observation. Thus the exploratory spirit of the early modern age was created in part by the revival of antiquity, and the science we know today owes a great debt to such defunct disciplines as astrology, alchemy, humoral medicine, and physiognomy. These disciplines were once part of the foundation of education and only disappeared from scientific discourse when the paradigm of the four elements as the building blocks of all nature was disproved. Today, these pursuits are relegated to the realm of the occult, abandoned as curiosities along the inexorable road to modern empirical thought. Such has been the fate of astrology and humoral medicine, which depended on the paradigm of the four elements, humors, and temperaments, to which melancholia belonged. With their demise also went the intimate interdependence of science and religion, which required God’s example and guidance in every intellectual pursuit.

Before the Enlightenment, knowledge was regarded as a whole, and the compartmentalization of the intellectual world into multiple disciplines had not yet taken place. Indeed, the term “science” encompassed under a single rubric disciplines that we now consider separate entities, including medicine, chemistry, cartography, and mechanics. The international scholarly community was a relatively small, cohesive group, though its members resided in diverse locales. Little attention was paid to a scholar’s country of origin, as long as he published in Latin, the universal language of learning and the church. The lay public became aware of scholarly discoveries via translations or condensed versions of scholarly books, usually well after their introduction to the academic community. When Robert Burton’s massive and scholarly Anatomy of Melancholy appeared first in English in 1621, it made an immediate impact. Here was a hefty compendium of knowledge devoted to a topic of great interest and contemporary relevance, which contained two thousand years’ worth of authoritative knowledge in a single source. Punctuated by vivid descriptions of the psychic and physical aspects of melancholia, it provided a means of bridging the gap between the material and the spiritual realms, making melancholia one of the most distinctive and distinguished topoi of the early modern era. By the time Burton began his definitive study, however, melancholia had long been a fixture of common wisdom, having already evolved into a hallmark of privilege and fashion associated with learning and gentility. Simultaneously, the pathology of melancholia was renewed as a subject of profound interest among the academic community, even as the idea of melancholia became a fixture of everyday life. Artists and physicians were especially cognizant of the bodily and mental symptoms associated with black bile. By means of specific physical attributes, gestures, and facial expressions, a man’s health, intellect, piety, and social status could be both diagnosed and represented.

Methodology

Today, artists and physicians may meet occasionally over cocktails, but the two professions were once co-dependent. The medieval fusion of art and medicine was born of practical necessity, as the raw materials for both were bought from common suppliers and manufactured by the same means. In many cities, doctors and painters alike belonged to the guild of Saint Luke the Evangelist, who, though a physician, was inspired by a vision of the Virgin to paint her portrait. By the time the cultural phenomenon of melancholia peaked in the seventeenth century, both artists and physicians inhabited court circles, aristocratic households, and the fringes of university life. Consequently, many artists had a fairly sophisticated knowledge of medicine, especially if they aspired to gentlemanly or academic status.

The segregation of knowledge in present-day academia stands in stark contrast to Saint Luke’s disciplinary synthesis. In fact, early scholarship did not treat the study of religion, philosophy, medicine, and literature as isolated pursuits, and substantive contributions to one or another field were not limited to narrowly focused specialists. The modern perception of art as predominantly emotional and creative, and of science as essentially logical and rational, did not exist. Such cultural expectations account, in part, for why the field of art history has been slow to draw upon the full panoply of early scientific knowledge, including its occult and magical elements, for interpretive tools. The religious truths and antique paradigms that once gave life to such obsolete pursuits as alchemy and astrology were discarded long ago by modern scientific rationalism. As a result, much of the existing scholarship on the relationship between art and science has arisen from a desire to understand and document the origins of modern disciplines—those universally accepted today as “scientific”—such as cognitive science, chemistry, anatomy, and botany. In the early modern era, however, these sciences were in the embryonic stages of development and had not yet been codified as specific disciplines.

This book did not start out to be a self-consciously “interdisciplinary” study, though it ultimately took this form after a decade of research. My intent was to be guided by my own specific interests and training and to follow the questions where they led me. I soon discovered that they led me everywhere, for the topic of melancholia is of enormous importance to many fields. However, the pitfalls of this approach are legion. Academic disciplines have evolved over time into well-defined entities, each with its own descriptive language, favored methodologies, and fashionable debates. As a result, scholarly studies devoted to melancholia, though vast in number, are also discipline-specific, often sharing few common secondary citations. It would seem that although the historical and cultural importance of melancholia is recognized across the broad scholarly spectrum, isolated disciplines take little notice of one another. For every statement made in one field, an army of specialists in other far-flung disciplines stand ready to confirm or dispute it.

Contributing to this disciplinary isolation is the fact that academic fields do not interpret historical circumstances and images in the same way. Melancholia may be a household word to a literary scholar who studies Shakespeare’s plays or a musicologist investigating Dowland’s songs. By contrast, the visual conventions, iconographical tools, and interpretive metaphors that art historians take for granted may be alien to scholars trained in other disciplines. By using early modern texts and images as supporting evidence, and avoiding the often unwieldy verbal apparatus of critical theory and protracted stylistic analysis, this book presents the melancholic persona as the product of an accessible and pervasive intellectual paradigm that remained remarkably consistent throughout two thousand years of discourse.

Art history lags behind other academic disciplines—comparative literature or the history of medicine, for example—in the recognition of melancholia as a powerful interpretive signifier. Even scholarly studies devoted to the social status of the artist as communicated in self-portraits (the subject of chapter 5) do not mention the pervasive melancholic topos. This lacuna also informs the study of seventeenth-century Dutch art, which I present as the triumph of the melancholic persona. Led by the pioneering work of such scholars as Dirk Bax and Eddy de Jongh, which emphasize vernacular textual sources, specialists in this area often seek a one-to-one relationship between word and image, such as exists in the proverb and emblem traditions. This rich methodological model, which privileges vernacular texts above all others, has provided crucial insights into the motivations of Dutch artists. But it has also led to intense disagreement about the extent to which these artists were influenced by intellectual trends in other countries, particularly England.

Melancholia’s descriptive paradigm was not limited to any particular language, country, or time. It would therefore be impossible to prove that an artist intended to illustrate literally any of the descriptive quotations found in the following pages. The snippets of text from all manner of written sources that appear here are intended only to provide period commentary on familiar and embedded cultural constructions. Likewise, the bibliographical citations that support this book do not claim to be comprehensive. A list of studies devoted to Rembrandt alone, an area that has burgeoned in the wake of the four-hundredth anniversary of his birth in 2006, would fill an entire volume. The endnotes in this book are therefore limited to representative sources, even if that means that some worthy studies, less germane to the topic at hand, go uncited. This is true also of the illustrations, which were chosen to represent and typify many others that mutually reinforce one another. I am confident that readers will call to mind other parallels and examples, once they become aware of melancholia’s multiple frames of reference.

The concept of melancholia was universal. This book therefore accepts Lisa Jardine’s lucid demonstration of the early modern connections between England and Holland, which shared artistic, intellectual, dynastic, and political values. I treat the cultural construct of melancholia as yet another example of the mutual concerns of the two nations. Seventeenth-century Holland absorbed the cutting-edge beliefs that informed the rest of European culture, and that incomparable Dutch painters transmitted to a sophisticated international audience. More broadly speaking, evidence of Holland’s important role as a major player on the international stage is readily apparent in the global concerns of Dutch merchants and intellectuals. The pan-European awareness of melancholia is one more example of the seamless exchange among European nations in the early modern era. In order to recognize its powerful social and cultural implications, we must first discard what Jardine calls “history’s customary petty nationalism” and recognize melancholia as a cultural commodity that knew no geographical or linguistic borders.

Organization of the Book

The first inclusive study in English to address the premodern phenomenon of melancholia and its visual representations was Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl’s monumental Saturn and Melancholy (1964). Intended to provide background and discussion of Dürer’s Melencolia I, this book chronicles the evolution, over two millennia, of the iconography of melancholia in its philosophical, religious, and scientific contexts. Informed and dazzled by this lofty study, the field of art history accepts Dürer’s seminal engraving as a personal declaration of genius and a reflection of the artist’s intellectual and professional aspirations. Succeeding generations of scholars have continued to debate its general theme and iconographical fine points. But none has approached the thoroughness and persuasiveness of Saturn and Melancholy, which pooled the brilliance of three of the most prominent intellectuals of the mid-twentieth century. Specialized studies on melancholia in art have appeared in recent years, and the topic is finding its way into academic conferences. The most important recent example of this nascent interest is the comprehensive exhibition Mélancolie: Génie et folie en Occident, mounted in Paris and Berlin in 2005. The accompanying catalogue dissolved disciplinary barriers within a broad conceptual framework, linking themes ranging from portraiture to landscape and dating from the ancient to contemporary eras, under the common rubric of melancholia. I am guided by the creativity and inclusiveness of this exhibition in my presentation of melancholia from multiple yet compatible points of view.

This book focuses on three exemplary male archetypes of the melancholic persona: the hermit, the lover, and the scholar, as represented in art from approximately 1500 to 1700. Aspects of each of these three types were subsumed within a fourth theme, the artist’s self-portrait, which combined the qualities of piety, passion, and wisdom associated with saints, gentlemen, and intellectuals, respectively. I begin by unapologetically accepting Saturn and Melancholy’s historical and iconographical accounts, and by fully acknowledging the subject of Dürer’s print as representing the melancholic persona. I demonstrate how succeeding generations of artists expanded what were, to their minds, standard astrological and humoral symbols in order to create and define an elite identity that did not depend on noble blood or material wealth. By manipulating physiognomic elements such as complexion and bodily pose, as well as formal qualities of light, color, and ambiance, artists appealed to an early modern audience, whose gaze was trained to discern the invisible internal self by external appearances. What we now call “body language” was justified by scientific concerns such as optics, botany, and brain anatomy, as well as the now obsolete disciplines of humoral medicine and astrology. I maintain that the look of melancholia was purposefully achieved by means of several calculated stylistic and iconographic choices.

Chapter 1, “Saturn’s Privileged Realm: Meaning and Melancholy,” introduces the concept of melancholia as it evolved from antiquity through the seventeenth century, when it became a fashionable disease. This chapter is not intended to offer a comprehensive historical account but rather isolates and draws out specific strands, represented in the works of art that are the focus of succeeding chapters. Common throughout its long history is melancholia’s association with the planet Saturn, the element earth, and the bodily humor of black bile. Because the condition could be either hot or cold in nature, melancholia was ambivalent in its very definition. This brief history emphasizes the inherently oppositional nature of melancholia, embodied in such contrary qualities as light and dark, hot and cold, active and passive, order and chaos, good and bad, elite and popular. These conflicting qualities were maintained over two thousand years of discourse, being first articulated in Greek humoral theory and recurring in Arabic astrology, Christian morality, medieval chivalry, and Renaissance Neoplatonism. The curiously dichotomous nature of melancholia—which conferred joy and grief, pain and privilege, sin and virtue on its victims—exerted a powerful influence in the wake of Dürer’s emblematic Melencolia I (fig. 1).

The historical information provided in this chapter underscores the premise of the book, which is that, in the two centuries following Melencolia I (1514), the condition came to be perceived and portrayed in art not only as a marker of privilege but also as a stylish disease. In the seventeenth century, the cultural construction of melancholia was international in nature, having been reborn in the secular universities of England and northern Europe. From there, it was transmitted to the popular sphere by means of “crossover” texts such as Robert Burton’s massive compendium The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), becoming a dominant topos in music, literature, and art. In a larger sense, the pervasive imagery of melancholia that followed reflects society’s evolution from a medieval mindset to a modern one.

Chapter 2, “Privileged Piety: Religious Melancholy,” explores the melancholic model that prevailed in art before Dürer’s engraving and persisted beyond it. Christianity derived the concept of the pious and melancholic holy man from Aristotle, who linked creative genius and prophecy with the state of enthousiastikon (possession or inspiration). Before Renaissance philosophy and science invented new secular models, the saturnine qualities of privilege and intellect were associated with extreme piety. But Christian morality also attributed the sins of avarice, sloth, and sorrow to the prevalence of black bile in the body, which explained the physical lethargy, misanthropy, and incapacitating mental depression characteristic of melancholics. This chapter examines the widespread Renaissance cult of the intellectual, first embodied by the scholarly Saint Jerome, which corresponds to the increased fascination with melancholia in humanist circles and a parallel movement in art.

Dürer depicted Jerome at least fifteen times, and the generic theme of the pious hermit was renewed in the Counter-Reformation age, when theologians supported a return to the rugged asceticism of the early church fathers. In the seventeenth century, references to early modern scientific theories supplemented the traditional iconography of Saturn and melancholy inherited from the medieval tradition. Pre-Enlightenment theories of brain anatomy, which defined melancholia as an infection of the faculty of reason, are suggested in Dürer’s Lisbon St. Jerome (fig. 21). Succeeding generations of artists improvised on Dürer’s theme, combining physiognomic and anatomical references to melancholia with astrological allusions to Saturn. Seventeenth-century paintings of hermits augment the accouterments of Jerome’s study—books, hourglasses, dividers, skulls, etc.—with botanical references, which serve as iconographical reinforcements of saintly piety, deprivation, and solitude. Rembrandt, however, was Dürer’s truest protégé, despite the passage of more than a century. By marshaling all the drama of his virtuoso printmaking technique, Rembrandt tangibly evoked the profoundly dark vision of melancholia first suggested by the shadowed eyes of Dürer’s muse.

Chapter 3, “Privileged Passion: Love Melancholy,” examines “erotomania,” or love melancholy. Unlike modern evocations of romantic love as an idyllic state, erotomania was considered an illness requiring a cure. Its physical and mental symptoms were instigated by the heated fires of erotic yearning. The melancholic lovers in English miniature portraits are the focus of this chapter. They represent a study in contrasts—wretched yet ecstatic; heated by the internal flames of passion yet pale and cold to the touch; morose yet appealing. The fashionable young men and women in these portraits, who lock their gazes intently with our own, seem to express a sort of delicious misery as they revel in their suffering.

The elegant lovers who pine and sigh their way through English courtly culture were men of sensitivity and depth who wore their passion as a badge of privilege. The bold gaze of the women in these miniature portraits, by contrast, defies the rules of proper female behavior, which warned of directly engaging the eyes of men. Several conventions are integral to our understanding of this startling departure from artistic tradition, including the chivalric concept of love at first sight, the hypnotic effect of the beloved’s gaze, and the power of an image to substitute for the beloved. Early scientific tradition explained these representations as active instigators and fortifiers of passion, harnessing the interdependent association of eyes, heart, brain, and passions in the cognitive thought process. The very act of looking was considered capable of kindling the mutual fires of love by reinforcing the appearance of the beloved in memory. The sometimes unnerving emotional intensity of these portraits, and the physical response they inspired, was intended not for strangers but for one person only—the lover. This chapter interprets these private and personal portraits as more than inert, beautiful objects of contemplation that recorded the unique appearance of an individual. They were also active instigators of what could be termed a type of consensual, visual sex involving the viewer and the portrait subject.

Chapter 4, “Privileged Work: Scholarly Melancholy,” applies the intellectual purview of melancholia to depictions of students and scholars. The popular subject of the forlorn thinker, dressed in academic robes and working amid his books, is the twin of the melancholy hermit who cogitates in his dreary cave. In art, the implements of Saint Jerome’s study fill the temporal environments of both mature scholars and youthful students, providing a saturnine context for both youth and old age. When depicting the scholar’s habitat, painters employed the limited color scheme of melancholy earth, using exaggerated tenebroso to suggest Saturn’s perpetual night. Students and sages alike exhibit dark faces and shadowed eyes, as they strike melancholia’s familiar gestures amid the accouterments of their profession. The traits of misanthropy, lethargy, and avarice provide subcontexts for several scenes of scholars in their dingy studies, suggesting the compatibility of melancholia with vanitas. Reinforcing this connection is the Leiden still-life tradition, which depicts piles of well-worn books, skulls, timekeeping devices, and musical instruments. These works, distinctive in their sobriety and painted entirely in monochromatic tones of ocher and brown, convey the earthy realm of melancholia both in palette and in the choice of assembled objects.

Several seventeenth-century portraits expand the traditional iconographical purview of melancholia by alluding to Saturn’s realm in original ways. By jettisoning traditional material symbols—books, globes, hourglasses, etc.—they favor more subtle allusions to the psychic qualities of melancholia. Portraits of men noted for their intellectual accomplishments—poets, philosophers, and connoisseurs—show them peering distractedly from amid deep shadows, their eyes shaded and sometimes obscured by the brims of their hats. As in the murky environs of Saint Jerome’s study, this visual ploy purposely evokes the melancholic’s clouded vision, caused by burned, black vapors interposed between the brain and eyes. The attributes of melancholia, suggested by the physiognomy, costume, and pose of these sitters, reinforce the nobility of spirit, piety, and intellectual acumen that distinguished early modern gentlemen.

Chapter 5, “A Privileged Profession: Artists and Melancholy,” demonstrates how aspects of the hermit’s solitary martyrdom, the lover’s aristocratic passion, and the scholar’s misanthropic intellect merged to create a fourth subject, the artist’s self-portrait. Artists’ professional and personal identification with melancholia was heralded by Dürer, who appropriated the intellectual status of the melancholic in both life and art. In the centuries that followed, artists continued to advocate for membership in the brotherhood of Saturn, portraying themselves as proudly succumbing to its dominance. Contrasting starkly with earlier portrait traditions, which favored neutral facial expressions, artists frown, scowl, and sulk despairingly, locking eyes with the viewer from shadowed depths. Blessed and damned by genius, such self-representations display melancholia’s dynamic and ambivalent qualities.

Artists, most of whom were not of noble blood, and whose fortunes were tied to the economic realities of supply and demand, substituted innate, God-given talent as a criterion for their evaluation by society. In their efforts to expand the medieval mercurial perception of the artist as anonymous craftsman, they searched for ways to emphasize the integrity and uniqueness of their profession. The melancholic pose fulfilled popular expectations of how artists should look and, most important, how their work defined and enhanced their social roles and capabilities. Changes in theories of brain anatomy further aided artists in their bid for professional integrity. The displacement of the rational faculty by increased emphasis on the visual nature of imagination in melancholia allowed artists to claim the discipline and rational objectivity of scholars while remaining susceptible to the noble passion of melancholia. As a result, artists could claim the privilege of melancholia without the stigma of insanity.

Seventeenth-century fashion mandated the evocation, by costume and gesture, of the glamour and mystery associated with melancholia. Painters assume the ideal of a scholarly courtier in many self-portraits, donning the melancholic “uniform” of broad-brimmed hat and felt cloak or even academic caps and gowns. Saturn’s psychic haze is eloquently suggested by the purposeful manipulation of light and shadow, which invites the viewer to perceive the world through melancholic eyes. Artists of every European nationality employed this visual strategy in portraits that depict faces half-lit, with eyes obscured by shadow. This ploy, often enhanced by surroundings of murky darkness, suggests melancholia’s ambivalence and bipolarity. Considered in this context, self-portraits demonstrate that early modern artists had a hand in their own labeling as men of quality, learning, and piety.

Chapter 6, “Wine, Women, and Song: Melancholy Mediated,” focuses on bucolic nature, erotic stimulation, and the music of stringed instruments as remedies for melancholia. These things commonly appear in genre scenes of the artist’s atelier, scholar’s study, and gentleman’s home, where they provide environmental support for the acquisition of balance in their bodies, minds, and lives. Such controlled glimpses of comfortable, cultivated work spaces correspond to descriptions of the ideal gentleman-scholar’s studiolo. In these paintings, antisaturnine elements are displayed almost as talismans, emphasizing their tangible powers against the health hazards of privilege and passion. The presence of musical instruments in these scenes does not indicate vice or vanity, as has been suggested. Unlike art, the practice and theory of music belonged to the venerable quadrivium of medieval knowledge and was always numbered among the liberal arts, a position to which art could only aspire. Expensive musical instruments were essential components of a cultivated life, and the ability to perform music was a prerequisite for gentlemanly status. The violins, lutes, and harpsichords that populate the artist’s studio thus represent music’s ability to heal the soul, encourage sobriety, and achieve humoral balance. Their sound was a powerful antidote to negative passions, and their medical effectiveness was made even more potent by the act of performing.

As embodiments of instinct, emotion, and instability, women were alien entities in the male domain of melancholic genius. In genre paintings, women are relegated for the most part to the safe roles of useful servants, good companions, erotic stimulants, and pretty, decorative objects. Like the rich foods, expensive musical instruments, and elaborate domestic furnishings that often surround them, virtuous, attractive, well-kept women reinforce the wealth, privilege, and righteousness of the haute bourgeoisie. In marriage portraits that depict scholarly husbands surrounded by the accouterments of melancholia, faithful, genial wives provide the necessary balance essential for the attainment of health and well-being. Furthermore, the sanguine planet Venus ruled women’s socially sanctioned roles as wives, mothers, and muses, as well as the metaphorical female realms of beauty and nature. Physicians routinely prescribed venereal stimuli as purges against Saturn, and women were the most powerful purveyors of this power. Their presence among the musical instruments, landscapes, and domesticated dogs in the saturnine study reinforces these spaces as healing environments.

The Epilogue to this book, titled “Melancholia Denied and Revived,” briefly summarizes the evolution of the concept of melancholia after the seventeenth century. Medically, the basic paradigms in support of humoral theory and astrology were gradually replaced by facts derived from empirical investigation. Thus the special qualities of the melancholic personality noted from Aristotle onward—rebelliousness, uniqueness, and superiority—were no longer fashionable by the late eighteenth century, which championed liberty, equality, and fraternity. Eighteenth-century artists gradually jettisoned the concept of the rebellious, misanthropic genius in favor of the mild-mannered courtier. The superior man presented a sedate, cool, and impartial façade, suggesting the tempered blood that flowed within him. Consequently, portraits from this era display a sense of ease and urbanity, devoid of the dark, tenebrous tones that defined Saturn’s domain.

In the nineteenth century, the recognition of mental illness as a specific category of disease gained ground, culminating in the Freudian revolution of the fin de siècle. But even as medicine advanced to the status of an elite profession, art looked backward, steeped in historic revivalism. In one of the great pendulum swings of history, the eighteenth-century gallant was displaced by the rebellious romantic who shunned society while also believing himself above it. In this revivalist fervor, Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy flourished anew, as artists harnessed its ancient truths in support of the romantic antihero. But nineteenth-century creators did not consider themselves passive casualties of warring planetary influences and spontaneous humoral imbalances; rather, they were active initiators of their own victimization. In their borrowing of time-honored stylistic and iconographic strategies, artists appropriated the past even as they proclaimed their utter originality. Their self-portraits employ the full gamut of traditional melancholic iconography, inspired anew by subsequent editions of Burton’s popular treatise.

Today, the melancholic persona persists as an embodiment of withdrawn, alienated genius, crafted in response to the violent and depersonalizing forces of the modern world. Despite advances in art and science, the topos of the dispirited intellectual continues to function metaphorically as a locus for society’s fears and tensions, as it has for more than two millennia. Although Dürer may have intended his iconic engraving as an expression of his personal struggle, its message reached far beyond its time and place to inspire creative artists for generations. Melencolia I was not the culmination of an idea but the beginning of one.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.