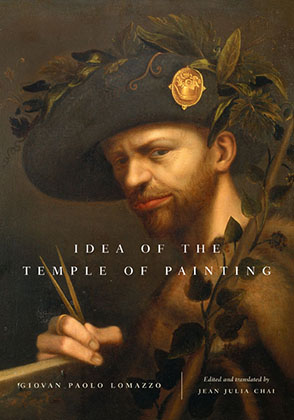

Idea of the Temple of Painting

Giovan Paolo Lomazzo, Edited and translated by Jean Julia Chai

“Chai’s nuanced introductory essay deftly places this late effort by the blind artist into both the context of Lomazzo’s life and interests (the mascot of his deliberately unfashionable academy was a wine porter), and the complicated strands of 16th-century society and books. An abstruse author with a taste for allegory and the occult, Lomazzo, hitherto scarcely available in English, is presented with sympathy and clarity. Highly recommended.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Chai’s nuanced introductory essay deftly places this late effort by the blind artist into both the context of Lomazzo’s life and interests (the mascot of his deliberately unfashionable academy was a wine porter), and the complicated strands of 16th-century society and books. An abstruse author with a taste for allegory and the occult, Lomazzo, hitherto scarcely available in English, is presented with sympathy and clarity. Highly recommended.”

“Carefully edited and practically organized, [Idea of the Temple of Painting] aims at opening the writings of Lomazzo to new audiences, and opens fresh avenues to approach this versatile author’s ideas.”

“What is startlingly new in both the Trattato and the Idea is Lomazzo’s theory of human movement and expressive emotions, and this contribution is expertly evaluated by Chai. She rightly says that Lomazzo’s ‘choosing the right expression’ in his theory of ‘represented emotions’ ‘was not just a matter of proper decorum; it included dialoguing with the divine’. . . . Today, with Chai’s guidance, we can read this author as an artist fascinated by the imagined and represented human body—and its subtle control through the pseudosciences of astrology and physiognomy—and the artistic and ecclesiastical decorum of the day.”

Jean Julia Chai is a translator and lives in Paris. She received her Ph.D. in art history from Harvard University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

On the Translation

Introduction

1 The Temple of Painting: A Mnemonic Image

2 Artist, Academician, and Dreamer

3 Discernment in Painting

4 From Moto to Maniera

5 An Aesthetics of Fascination

6 The Delayed Reaction

Idea of the Temple of Painting

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

The Temple of Painting: A Mnemonic Image

Imagine walking into a small, round classical temple and immediately being stopped short—blinded by a cascade of light streaming in from above that reflects off the surface of a marble floor. As our eyes grow accustomed to the interior space, seven colossal statues emerge from the shadowy walls. They serve as columns to support the entablature, and, above that, a dome and fenestrated lantern. We examine the face of one figure and gradually discover the features of Michelangelo: high prominent forehead, beady little eyes, broken nose, scraggly beard, and cropped hair. Cast in lead, the Florentine master carries the tools of his trade and stands proudly on an elaborately carved pedestal that depicts artists formed from his alter ego, Saturnine characters gone bad—anxious, tedious, envious, desperate types—who warn the visitor against any similar folly. Continuing along the wall of the edifice, we next encounter a statue of Gaudenzio Ferrari, a sixteenth-century Piedmont painter of the finest kind who worked extensively in Milan. His Jovian aspect forms a pleasant contrast to the greedy, tyrannical counterparts engraved on his pedestal. The third statue, made of iron, represents Polidoro da Caravaggio. And so we proceed around the perimeter of the circle, identifying the other statues, one by one, as Leonardo, Raphael, Andrea Mantegna, and Titian, each cast in a different metal and mounted on a decorated pedestal displaying the dark flip side of each artistic temperament. Where are we? Who are these artists? We are standing in the ideal Temple of Painting conceived by Giovan Paolo Lomazzo in 1590. These eminent masters are the gods he chose to govern this art.

The circular wall behind the seven statues is divided into five equal tiers signifying the theoretical parts of painting. Proportion sits at the base, supporting movement, color, light, and perspective, in that order. Above the frieze and cornice soars the dome. Its two levels represent the practical parts of painting: composition and form. We pause a moment to take this all in. Visually, the artists occupy the space vertically, while the parts of painting divide it horizontally. Seven governing artists or styles intersect with seven parts of painting. Based on his planetary disposition, each artist has his own way of handling proportion, movement, color, light, and all the other parts of painting. Thus each part has seven different manners or styles. The Saturnine proportions used by Michelangelo, for instance, differ from the Jovian ones of Gaudenzio Ferrari, and even more from the Venusian measurements employed by Raphael. Likewise, Polidoro da Caravaggio’s Martian colors are not those of Leonardo or Titian. The intersection of style with pictorial elements finds form in the art of these seven masters. All of painting is exemplified by their irreducible styles. Our first impression of the Temple is of a harmonious, well-built monument, airy and luminous, uncluttered by decoration, and focused on highlighting its seven noble inhabitants. For the design, Lomazzo acknowledges having been inspired by Giulio Camillo in L’Idea del theatro. He praises the famous theater and admits—in a moment of rare modesty—“compared to that construction, mine is much humbler and cruder.”

Camillo’s theater was indeed a grand affair. It pretended to contain nothing less than the entire universe. Adapting a Vitruvian plan, Camillo described a vast auditorium divided by seven aisles, each devoted to one of the seven planetary gods. Each aisle had seven rows that rose progressively higher, representing everything from the supercelestial world, located at floor level, to the elemental world, with human activities in the upper tiers. On every row and in every aisle, a door painted with a significant memory image recalled to the viewer a specific location in the universe. From the stage, one surveyed the marvelous spectacle of forty-nine mnemonic paintings that encompassed every color and facet of creation, revealing, through an underlying order, hidden correspondences among the far distant corners of the cosmos. The memory theater enabled the human mind to grasp the universe. But that was not all. It had its hermetic secrets as well. For the mnemonic images also functioned as talismans, attracting astral forces down into the theater. And as they energized the memory, these powers unified it with the higher images or First Causes, thereby intimately associating the viewer with the divine.

Lomazzo never saw the actual wooden theaters Camillo had built in Venice and Paris during the early 1530s. The Venetian version was said to have been large enough to accommodate two people at the same time. In addition, it held thousands of pages from Cicero, Virgil, Boccaccio, and Petrarch, filed away in coffers under the appropriate image—should the viewer’s memory ever fail him. The invention of this theater made Camillo a renowned celebrity. Yet however admired by the king of France, the great man returned to Italy in 1543 without a pension. The Marchese del Vasto, governor of Milan, seized the opportunity to have such a brilliant mind at court. Enjoying the governor’s personal favor, Camillo thrived in the Lombard capital, impressing aristocrats and intellectuals alike, until his sudden death in 1544. Published posthumously in 1550, his L’Idea del theatro (based on the lectures delivered to Del Vasto over the course of five mornings) initiates the reader into the essential mysteries of the theater. So when Lomazzo compares his Temple to Camillo’s construction, it is no fortuitous choice but an allusion to a well-known monument, alive in the literary imagination of the Milanese public and one they had adopted as their own.

Precisely how are the two structures similar? And to what extent did Lomazzo intend to carry out the comparison? Though “humbler” in scope, the Temple of Painting is also a microcosm organized around the dominating influence of the seven planetary gods. It too operates as a kind of mnemonic machine, inviting the apprentice to enter and actually experience the architectural environment, which unfolds before him the marvels of the pictorial universe. His attention is drawn to the impressive metallic sculptures, richly figurated pedestals, and horizontal divisions of the walls that designate the major elements of his art and, like memory images, provide the key to unlocking immense stores of knowledge and penetrating its deepest secrets. Apart from the structural resemblance, the Temple also shares the theater’s metaphysical aspirations. Universal lighting from above indicates a divine presence that filters down the walls, through the parts of painting, into the seven chosen masters of the Temple. The Neoplatonic belief in a descending cosmic influence implies a harmonious correspondence between every link in the chain. This means, from an aesthetic point of view, that harmony is necessary among all the parts in order for painting to receive beauty or grace from above, ultimately resulting in the coherent expressive styles of all the governors. While not talismans in Camillo’s sense, the statues nonetheless possess a certain aura, derived from traces of the divine, channeled into them by the flow of planetary influence that relates and unifies all of painting according to these seven styles.

Unlike the theater, the Temple places particular emphasis on the manners of the different planetary temperaments. Saturnine temperaments like Michelangelo’s generate a style that expresses “profound contemplation, intelligence, gravity, judgment,” while Venusian personalities like Raphael’s emanate “sweetness, loveliness, kindness, desire,” or Martian types, “spiritual strength, the passion of animosity, the power to act, and the immutable vehemence of the soul.” Through these means, Lomazzo offers a psychological explanation for the variations in stylistic expression, opening the door to the possibility of multiple styles, and ultimately, individual expression. For this reason, the Temple of Painting is more than a mere mnemonic device. It not only displays the whole range of artistic styles but also encourages the novice—using discernment (or discrezione)—to determine his own manner, expressive of his own temperament. As an afterthought, Lomazzo adds the artist’s discernment as an eighth part of painting and locates it on the floor of the Temple as the foundation of all. In so doing, he obliges the debutant painter who enters the sacred edifice to exercise a certain self-reflection that will enable him to discover his individual style and eventually define a place in the universal order.

In 1584, Lomazzo published a massive encyclopedic treatise on painting entitled Trattato dell’arte della pittura, scoltura et architettura (which Julius von Schlosser would later call the Bible of Mannerism). The seven chapters of this work were each devoted to one of the seven parts of painting. Idea of the Temple of Painting, appearing six years later, was meant to serve as its introduction or—in the author’s words—its “abstract and summary.” In fact, the two treatises were conceived at the same time. Earlier versions of Idea of the Temple of Painting originally formed sections of the Trattato, but these pages were subsequently edited out, revised, and printed in 1590 as the separate volume we know now. The invention of the Temple of Painting conceit was the reason for the distinct, new work. It condensed all the amassed knowledge about painting—the contents of the Trattato—into a single charged image accompanied by a text that provided, like Camillo’s L’Idea del theatro, the basic operating instructions. Moreover, it theorized the knowledge about painting, giving it a metaphysical dimension that justified its place in the world. Together, these two treatises contain all of Lomazzo’s essential ideas about art and all his formal writing on the subject. An unpublished manuscript known as the Libro de sogni (ca. 1563) offers some interesting youthful impressions; Della forma delle muse (1591) may be considered an addendum to the Trattato. Otherwise, a collection of poems, Rime ad imitazione dei grotteschi (1587), reveals his personal preferences among local and contemporary artists, as does the Rabisch (1589).

Lomazzo’s greatest contribution to the history of art is his special treatment of expression and, in its more developed form, self-expression. While Leonardo’s influence, very much alive in Milan, introduced Lomazzo to the possibilities of portraying emotion and movement in art (moto), his firsthand experience of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment made him truly conscious of how forcefully the artist’s personal expression could be conveyed through human figures represented in motion. In the Trattato, Lomazzo describes movement as the “part the most difficult to attain in all art, and also the most important and necessary to know,” exhaustively cataloguing the gestures, facial expressions, complexions, postures, and comportments appropriate to every emotion that might serve the practicing artist. Based on the privileged role movement plays in communicating the artist’s personal temperament, Idea of the Temple of Painting justifies an infinite variety of individual styles by sublimating the representation of emotion into the expression of the painting as a whole.

It is precisely this shift from representation to self-expression that makes the present treatise so important: it illustrates a transfer in interest toward the artist himself. By the mid-sixteenth century, the painted subject becomes increasingly a pretext for self-representation and hence affirmation of the artist. This introduction will demonstrate how Lomazzo’s theory supports such a shift. He clearly favored a fantastic, invented imagery to a purely mimetic one—what we will describe as a preference for artificial resemblance over the direct imitation of reality. In the absence of models, the artist is forced to rely entirely on his own discernment or visual judgment. Nowhere is this more necessary than in the difficult portrayal of movement and emotion. And nowhere, consequently, is the expression of his individual temperament more evident. In painting, the figural action not only tells the story but best expresses the artist’s personal style, setting the mode (as in music) with which all the other elements comply. The depiction of emotion, moreover, fascinates the spectator like no other part of painting: it moves him to experience and imitate what he sees. It is here that Lomazzo’s contribution has been truly felt, not only in the systematic study of emotions but also in the employment of theory to justify self-expression. His continuing legacy in the seventeenth century attests to his enduring influence in this domain.

However, it is not exclusively in hindsight that the outstanding merits of Idea of the Temple of Painting have been recognized. Lomazzo himself was fully aware of its importance and considered it the crowning achievement of his life. He saw to its publication just before the onset of a long illness that ended in his death on January 27, 1592. Fearing censure while Milan remained under the religious control of Archbishop Charles Borromeo, Lomazzo judiciously delayed its printing. He meant for the book to survive. More than another manual of precepts for artists, this final treatise addresses the purpose of art and its role in the world order. Such investigations naturally brought the author’s Christianized Neoplatonic views to bear on the matter, as well as his more clandestine beliefs in the magical writings of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim. This rare philosophical position is what defines his aesthetics and gives it, especially in this treatise, its unique voice and boldly original form.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.