On Antique Painting

Francisco de Hollanda, Translated by Alice Sedgwick Wohl, with introductory essays by Joaquim Oliveira Caetano and Charles Hope and notes by Hellmut Wohl

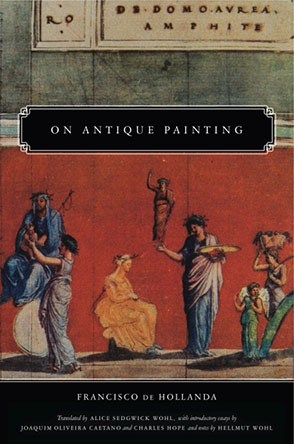

On Antique Painting

Francisco de Hollanda, Translated by Alice Sedgwick Wohl, with introductory essays by Joaquim Oliveira Caetano and Charles Hope and notes by Hellmut Wohl

“As the only English translation of this significant Renaissance treatise, On Antique Painting marks a contribution not only to the field of Portuguese literature but also to the study of humanism during the Renaissance.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“As the only English translation of this significant Renaissance treatise, On Antique Painting marks a contribution not only to the field of Portuguese literature but also to the study of humanism during the Renaissance.”

“Alice Sedgwick Wohl’s translation of Francisco de Hollanda’s De pintura antigua reintroduces an important voice to the larger discourse on Renaissance art theory and criticism. The Portuguese visitor was an alert witness to the aesthetic discussions taking place in sixteenth-century Rome; these he recorded in a series of dialogues in which Michelangelo was a dominant participant—and the reason the dialogues themselves have received much attention in modern scholarship. The dialogues, however, constituted Book II of Hollanda’s larger project, which was intended as a defense of the nobility of the art of painting and a program for realizing that goal. In the forty-four chapters of Book I, the author addresses all the major themes in the discussion of the art, but Hollanda’s most ambitious recapitulation of Renaissance aesthetics has been relatively neglected in art-historical scholarship. This new translation and critical edition will inspire reevaluation of Hollanda and the significance of his project.”

“On Antique Painting belongs to a tradition of English translations of important primary sources in Renaissance art history and theory, including Leon Battista Alberti's On Painting and Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists.”

“Alice Wohl’s long-awaited translation of Francisco de Hollanda’s On Antique Painting in its entirety (which includes not only the four dialogues, but the treatise!) is an excellent contribution to the distinguished Penn State series of translations of primary sources in Renaissance and Baroque art. A valuable contribution to the study of Renaissance art history, literature, theory, and many other topics of interest, including the culture of Renaissance Portugal and the classical revival of the Renaissance, this translation should renew interest in Michelangelo’s fascinating and controversial role in Hollanda’s dialogues. Introductory essays and endnotes provide the reader with a rich context for the understanding of this important work.”

“[Alice Sedgwick Wohl] is alive both to literal sense and to the difficulties posed by usage and stylistic conventions as employed in a language written four and a half centuries ago. With Hollanda she has taken on an especially difficult task, and has succeeded with colours flying. We now have for the first time in English the whole of Hollanda’s treatise. . . . We are all indebted to Sedgwick Wohl and her collaborators for an invaluable contribution to Renaissance studies.”

“The manuscript of Francisco de Hollanda’s Da pintura antigua (completed in 1548) is lost, or still to be identified. It was, however, translated into Castilian in 1563, and a copy in Portuguese was made in 1792, both probably using the same manuscript in Madrid, itself either the original or an early copy sent from Portugal to Spain. Alice Sedgwick Wohl has collated the texts of both versions in making her excellent translation from the Portuguese, occasionally following the Castilian text where ambiguities or lacunae appear in the Portuguese copy, but always noting the variant reading when she does so. She is an experienced, sensitive and reliable translator. . . . She is alive both to literal sense and to the difficulties posed by usage and stylistic conventions as employed in a language written four and a half centuries ago. With Hollanda she has taken on an especially difficult task, and has succeeded with colours flying. We now have for the first time in English the whole of Hollanda’s treatise. . . . We are all indebted to Sedgwick Wohl and her collaborators for an invaluable contribution to Renaissance studies.”

“Scholars of early modern culture and the history of art owe [Wohl] thanks. That her translation is clear and elegant, painstakingly attentive to the two early manuscripts available today, and sensitive to Hollanda’s ideas and milieu substantially increases our debt to her.”

Alice Sedgwick Wohl is an independent scholar and translator.

Joaquim Oliveira Caetano is Curator of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon.

Charles Hope is the retired former director of the Warburg Institute in London.

Hellmut Wohl is Professor Emeritus of Art History at Boston University.

Introduction

Note on the Early Years of the Portuguese Empire

Alice Sedgwick Wohl

Francisco de Hollanda (1517–1584): The Fascination of Rome and the Times in Portugal

Joaquim Oliveira Caetano

Francisco de Hollanda and Art Theory, Humanism, and Neoplatonism in Italy

Charles Hope

On Antique Painting

Book I

Prologue

Chapter I: How God Was a Painter

Chapter II: What Painting Is

Chapter III: On the First Painters

Chapter IV: Which Was the Fatherland of Painting

Chapter V: When Painting Was Lost, and When It Was Rediscovered

Chapter VI: How the Holy Mother Church Preserves Painting

Chapter VII: What the Painter Must Be

Chapter VIII: What Sciences Are of Use to the Painter

Chapter IX: By What Means the Painter Must Learn

Chapter X: The Second Thing from Which He Must Learn

Chapter XI: The Difference of Antiquity

Chapter XII: Why Antique Painting Is Celebrated and What It Is

Chapter XIII: How the Precept of Antique Painting Spread Through the Whole World

Chapter XIV: Concerning Some Precepts of Antiquity, and First, Concerning the Invention

Chapter XV: Concerning the Idea, What It Is in Painting

Chapter XVI: In What the Power of Painting Consists

Chapter XVII: Of the Proportion of the Body

Chapter XVIII: On Anatomy

Chapter XIX: On Physiognomy

Chapter XX: Precept for Antique Figures Standing Still

Chapter XXI: On Antique Figures That Move or Walk or Run or Fight

Chapter XXII: On Antique Figures That Are Seated and [Those That Are] Recumbent

Chapter XXIII: On Antique Equestrian Statues

Chapter XXIV: On the Ornament and Costume of the Ancients in Their Images

Chapter XXV: On Painting Animals

Chapter XXVI: On the Composition of Antique Historias

Chapter XXVII: On Painting Sacred Images, and First, Images of Our Savior

Chapter XXVIII: On Painting Images of the Invisible

Chapter XXIX: On the Divine Image

Chapter XXX: On Other Images of the Invisible, Such as the Virtues

Chapter XXXI: On Invisible Forms Such as the Vices

Chapter XXXII: On Painting Purgatory and Hell

Chapter XXXIII: On Painting Eternity and Glory, and the World

Chapter XXXIV: On Light or Brightness in Painting

Chapter XXXV: On Shade and Darkness in Painting

Chapter XXXVI: On Black and White

Chapter XXXVII: On the Colors

Chapter XXXVIII: On Decorum or Decency

Chapter XXXIX: On Perspective

Chapter XL: On the Point at Which the Painting Converges

Chapter XLI: On Foreshortening

Chapter XLII: On Statuary Painting or Sculpture

Chapter XLIII, Part 1: On Painting as Architect

Chapter XLIII, Part 2: On Painting as Architect

Chapter XLIV, Part 1: On All the Types and Modes of Painting

Chapter XLIV, Part 2: On All the Types and Modes of Painting

Table of Some Rules for Painting

Book II

Prologue

First Dialogue

Second Dialogue

Third Dialogue

Fourth Dialogue

Table of the Famous Modern Painters Whom They Call Eagles

Proverbs About Painting

Remembrance

Appendix A: Chronology of Popes and Rulers

Appendix B: Works by Francisco de Hollanda

Glossary

Bibliography

Subject Index

Index of Names and Places

Introduction

Note on the Early Years of the Portuguese Empire

Alice Sedgwick Wohl

Manuel I the Fortunate came to the throne of Portugal in 1495 and soon took up the program of maritime exploration initiated some eighty years earlier by his great-uncle Henry the Navigator. The Portuguese had by then explored the Atlantic islands and the west coast of Africa; Bartolomeu Dias had rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488; and Manuel’s predecessor, John II, had laid plans for a voyage to India to be led by Vasco da Gama’s father. Now, under Manuel’s sponsorship, Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon on July 7, 1497, in the carrack São Gabriel, accompanied by three other boats. The flotilla arrived near the trading port of Calicut on May 19, 1498, but on the return trip two boats were lost and the two others were separated. In the end, it was the caravel Berrio, commanded by Nicolau Coelho, that sailed back up the Tagus on July 10, 1499, with a small cargo of spices and precious goods, while Vasco da Gama did not arrive until early September. Their return spelled the end of the Venetian Republic’s domination of trade routes between Europe and Asia.

Other voyages ensued, and in 1500 Pedro Álvares Cabral, straying west on his way to India, encountered the coast of Brazil and claimed it for Portugal. Between 1503 and 1515 the naval commander Afonso de Albuquerque achieved a monopoly for Portugal of all maritime routes in the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. The expansion of commerce was accompanied by the formation of an empire that at its height stretched from Brazil to Southeast Asia and northward to China. Portugal reaped unimaginable riches: Afonso de Albuquerque reckoned that revenues from the spice trade alone came to a million gold cruzados a year, while trade in gold, silver, copper, sugar, brazilwood, and slaves brought in another eight hundred thousand.

To demonstrate his country’s achievements, King Manuel sent a spectacular embassy to the newly elected pope, Leo X. Led by the naval commander Tristão da Cunha, with the poet and chronicler Garcia de Resende as secretary-treasurer, the embassy arrived in the outskirts of Rome in February 1514, and on March 12 a procession of 140 persons and forty-three exotic animals and birds entered the city to parade the wealth of the Indies through the streets. The centerpiece was the white elephant Hanno, bearing a castellated silver platform and on it a casket with gifts of gold, jewels, and precious cloths. The pope became so attached to Hanno that he attended him when he lay dying in June 1516 and commissioned Raphael to paint a memorial fresco on a gate in the walls of the Vatican. Now vanished, the fresco and accompanying epitaph are known only from a drawing made by Francisco de Hollanda nearly twenty-five years later in his album Antigualhas (Escorial, Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo, inv. 28.I.20, fol. 31v).

But as Portuguese maritime expansion approached its zenith, the seeds of the decline that was to take place in Hollanda’s lifetime were sowed. To begin with, in 1496, as a condition of his marriage to Isabella of Aragon, the eldest daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, Manuel expelled the Jews (including some fifty thousand who had suffered expulsion from Spain in 1492). This caused intense social and religious disorder in the short term and more enduring harm to culture, finance, and the economy. Then the royal monopoly of trade that Manuel instituted in 1506 severely crippled the merchant class, which had been the mainspring of the voyages of discovery and the expansion of commerce. Instead of being invested in industry and agriculture, funds now went to the Crown, the aristocracy, and the church. Manuel’s son John III, who began his reign in 1521 as a liberal Renaissance prince, promoter of humanism, and patron of architecture and the arts, ended it in 1557 as a fervent defender of the Counter-Reformation. In 1536 he introduced the Inquisition, and when the first inquisitor showed little enthusiasm, he appointed his brother, Cardinal-Infante Dom Henrique (later King Henry I), as Grand Inquisitor. In 1540, through his ambassador Pedro de Mascarenhas, he applied to Pope Paul III for six Jesuit missionaries to send to his Indian dominions. Ignatius of Loyola designated Francis Xavier to join Mascarenhas, who was leaving for Lisbon the following day, March 11, 1540, with Francisco de Hollanda in his train. A year later Francis Xavier set out from Lisbon for India and never returned to Europe: he died on an island off the coast of China late in 1552, having, according to his Jesuit biographers, converted more than seven hundred thousand people to Christianity.

The two institutions—the Inquisition and the Jesuit Order—soon dominated Portuguese life and thought, altering the cultural climate abruptly and totally. The Inquisition’s regulations and procedures were secret, its jurisdiction covered every aspect of society, and any denunciation would set its terrible machinery in motion. The Jesuits were given authority over education, with significant consequences for intellectual activity, and, as tutors and confessors to the royal family and the aristocracy, they also gained influence over family and personal life. At the same time, commerce and the empire continued to expand under John III, with the missionary activities of Francis Xavier and the Jesuits keeping pace, and trade relations were established with China and Japan. The empire was under constant threat, however, from the Ottoman Turks in North Africa and the Indian Ocean, and from the French and pirates in the Atlantic, necessitating naval defenses at sea and the construction of fortresses on land to protect the trade routes. Portugal slipped into deficit and decline, and the period of dynamic development was over long before Philip II arrived in 1580 to claim the throne, inaugurating sixty years of union with Spain.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.