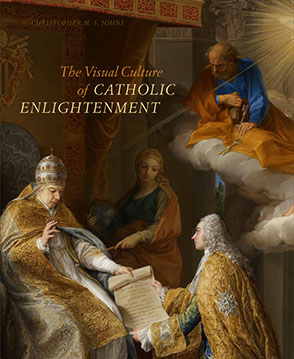

The Visual Culture of Catholic Enlightenment

Christopher M. S. Johns

“This groundbreaking book defines in depth and breadth the parameters of the Catholic enlightenment in eighteenth-century papal Rome, revealing the extent of the Church’s engagement with the secular enlightenment through papal initiatives for religious and more secular reforms that had a direct impact on the visual arts, the sciences, and many facets of culture. A remarkable range and variety of such projects are studied in a broader cultural context, including fascinating subjects such as the pope’s coffeehouse in the Palazzo del Quirinale, the founding of the Capitoline Museum, the restoration of the Arch of Constantine and the Colosseum, and the cult of the saints, to name but a few. In this lucidly written and richly researched book, Christopher Johns re-creates a complex historical fabric through the interweaving of art and culture during a period when Rome was the epicenter of the Grand Tour and Enlightenment Europe. The Visual Culture of Catholic Enlightenment should find a prominent and permanent place on the shelf of every student and scholar of eighteenth-century European visual culture.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“This groundbreaking book defines in depth and breadth the parameters of the Catholic enlightenment in eighteenth-century papal Rome, revealing the extent of the Church’s engagement with the secular enlightenment through papal initiatives for religious and more secular reforms that had a direct impact on the visual arts, the sciences, and many facets of culture. A remarkable range and variety of such projects are studied in a broader cultural context, including fascinating subjects such as the pope’s coffeehouse in the Palazzo del Quirinale, the founding of the Capitoline Museum, the restoration of the Arch of Constantine and the Colosseum, and the cult of the saints, to name but a few. In this lucidly written and richly researched book, Christopher Johns re-creates a complex historical fabric through the interweaving of art and culture during a period when Rome was the epicenter of the Grand Tour and Enlightenment Europe. The Visual Culture of Catholic Enlightenment should find a prominent and permanent place on the shelf of every student and scholar of eighteenth-century European visual culture.”

“This is a wonderfully comprehensive and stimulating book on the reforming impulse of the Catholic Church in the middle decades of the eighteenth century and its impact on art and visual culture, particularly in Rome. Christopher Johns addresses the question ‘What was Catholic enlightenment?’ from the disciplines of cultural, intellectual, and art history, and his research has resulted in a delightful book that will be of considerable interest to a wide variety of readers. Jansenism, sumptuary laws, enlightened Catholic ideas about the connection between faith and science, and coffee drinking in the middle decades of the eighteenth century are but a few of the topics he discusses. Art and architectural historians with an interest in Settecento Rome will find the book particularly interesting.”

“This magisterial study reveals the artistic vibrancy and intellectual ferment at the heart of the Catholic enlightenment. It upends old notions of the Church as a passive spectator of cultural change and reveals the myriad and dynamic ways in which the Roman hierarchy engaged the new ideas, new sensibilities, and new institutions that transformed Europe during the eighteenth century.”

“This magnificently illustrated book, which also explores notions of Italian Jansenism, makes us aware that eighteenth-century popes recognized the advantages of engaging with certain aspects of Enlightenment thinking and explains why utility was such a prominent topic of the Enlightenment era, not only in hagiography, but also in urbanization and architecture. . . . It should interest not only every student and scholar of eighteenth-century visual culture, but historians of the Church as well.”

“This is a wonderful, odd, challenging book. Wonderful because it is learned, informative, and engaging. Odd because it brings together ideas, events, and institutions that often are thought of as disparate and even antithetical. Challenging because by means of patient argument and accumulation of evidence, Christopher Johns disturbs many long-held assumptions about his subjects. . . . Johns opens our minds and eyes to creative acts, ideas, and works that have long been overshadowed by theories and events that seemed to have little or no positive relation to the religion of the time. This is not only a good book to look at, but a very good book to read.”

“The Visual Culture of Catholic Enlightenment will surely prove to be the fundamental text on its subject and, broadening our understanding of the Enlightenment more generally, makes an important contribution to many areas of scholarship.”

Christopher M. S. Johns is the Norman and Roselea Goldberg Professor of History of Art at Vanderbilt University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Rome and the Catholic Enlightenment in Historical Context

Ecclesiastical Reform and the European Public: Italian Jansenism and the Catholic Enlightenment

Sanctity and Social Utility: Making Saints in the Era of Catholic Enlightenment

The Papacy and the Patrimony I: Corsini Cultural Initiatives on the Capitoline Hill

The Papacy and the Patrimony II: The Expansion of the Capitoline Museums Under Benedict XIV and Clement XIII

Enlightened Administration and Polite Conversation: Clement XII and Benedict XIV on the Quirinal Hill

Roman Spaces of Catholic Enlightenment: Sacred Sites and Institutions of Social Utility

Popes, Episcopacy, and the “Good Bishop” of Catholic Enlightenment

Epilogue: Two Portuguese Earthquakes and the End of Catholic Enlightenment

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Rome and the Catholic Enlightenment in Historical Context

In reading your book entitled “la carità cristiana,” I learned what it is to be a Christian.

—Giuseppe Maria Crespi

Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665–1747), the celebrated painter of the Bolognese school of painting, in a letter to Lodovico Antonio Muratori (1672–1750), the leading Italian intellectual of the first half of the eighteenth century, paid tribute to one of the most influential texts of Catholic enlightenment. Muratori’s book, which appeared in 1723, was a clarion call by the modest priest from Modena for a system of Catholic charity based on individual assistance to the poor, sick, and disabled that constituted a better imitation of Christ than traditional pieties that emphasized endowments for chapels, masses for the dead, and gifts of property to the Church. Crespi, in his early seventies when he wrote to Muratori and doubtless thinking seriously about the nature of good works essential to Catholic salvation, found the arguments of Christian Charity persuasive. The survival of Crespi’s letter is fortunate, for it gives a surprisingly rare glimpse into the spiritual life of an eighteenth-century Catholic artist. An important premise of the present book is that artists—as well as the individuals and institutions that patronize them—live in society and engage, with varying intensity, in the broader cultural, social, spiritual, economic, and political contexts in which they live and work. The reforming impulse of the Catholic Church in the middle decades of the Settecento and its impact on art and visual culture, broadly defined, is the subject of my study.

To approach this complex theme coherently requires an answer to the question, What was Catholic enlightenment? Until relatively recently, most scholars considered the notion either oxymoronic or illusory, because the Catholic Church, according to received wisdom, was a tireless and indefatigable enemy of modernity. The eighteenth-century Papacy, however, recognized the advantages of engaging aspects of progressive thinking, and many in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, both in Italy and abroad, were sincerely interested in making the Church more relevant in the modern world and, above all, in reforming the institutions that governed society. Rather than a cogent ideology with a clearly identifiable agenda, Catholic enlightenment was more an attitude about how things could be made better for a larger segment of the body politic. Compromise, conciliation, and moderation were its defining characteristics, and it attempted to absorb as much of the new intellectual and social energy of the age of reason as was possible for an institution and belief system based on divine revelation and historical privilege. Thus Catholic enlightenment shared many of the assumptions and goals on which the broader, secular enlightenment was based.

Catholic enlightenment in the eighteenth century, although it manifested an idea of reform with a long history in the Church, differed fundamentally from past reforming tendencies, especially those advocated by the Council of Trent that initiated the Catholic Reformation, in its commitment to increasing accommodation and compromise with Catholic rulers. This spirit of “throne and altar,” highly problematic in many respects, was necessitated by the political weakness of the Holy See. Most Settecento pontiffs recognized the absolute necessity of cooperating with the secular governments to promote and protect the Church’s spiritual mission, which many progressive Catholics believed more important than the Secular Power, the term for the pope’s position as ruler of most of central Italy. The Roman hierarchy, as it came to understand the need for reform and spiritual renewal to preserve the Church’s authority in an increasingly secular era, began to feel an urgent need to get the house in order. Moreover, progressive reformers, having achieved the prominence in ecclesiastical government that was a major feature of enlightened Catholicism, were in a position to influence policy directly, both in Rome and throughout Catholic Europe. Although reforming efforts had mixed success, scholars’ recognition of the initiative in and of itself helps to position the papacy nearer the center of European enlightenment. The Roman version of the phenomenon differed little from its counterparts in other parts of Catholic Europe.

As the historian Dorinda Outram has pointed out, European enlightenment can no longer be considered an invention of a small group of French male writers; it cannot be identified with “a coherent intellectual programme.” Scholarly scrutiny of the enlightenments of the European and even global “periphery” underscores the atypical nature of the French version of enlightenment that Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) noted in his Lectures on the History of Philosophy (1825–26). In these, he argued, for example, that church and state became equal targets of French intellectual critique because France had not experienced the Reformation in the same way as Germany, and thus Germany’s enlightenment was more tolerant of the institutional status quo. Even in Scotland, where the mainstream of enlightenment was at its anticlerical and even atheistic extreme, an established group of Catholic writers shared a religious view of social progress similar to that of enlightened Catholic intellectuals in France, Germany, Austria, and elsewhere. The Italian historian Franco Venturi argued long ago that mainstream reformers and enlightenment elements of reforming Catholicism in Italy shared some interests, although his anticlericalism ultimately caused him to dismiss Catholic enlightenment reforms as insufficiently radical. The reform espoused by enlightened Catholicism sought neither to reinvent society nor to sweep away traditional institutions but to reform them from within.

French enlightenment ideas were disseminated throughout Europe, but the traditional notion that they were synonymous with those of the philosophes is erroneous. The Hapsburg court of Maria Theresa (r. 1740–80) in Vienna is a case in point. Moderate French Catholic authors of the preceding generation, such as Jacques Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704) and François de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon (1651–1715), were just as influential there as Voltaire and Denis Diderot (if not more so), and the rigorist tendencies so pronounced in French Jansenism (which Voltaire loathed) influenced ecclesiastical reform under Maria Theresa and her co-ruler and son, Joseph II (r. alone 1780–90). Most Catholic monarchs championed the “Christian Philosopher,” a characterization rejected by Peter Gay as oxymoronic. Separating progressive ideas from religious motivation gives an incomplete idea of ancien régime attempts to create a more reasonable government that existed, in theory, to make its citizens more prosperous, secure, and happy.

Reform Catholicism and Catholic enlightenment in Italy were influenced by the weight of history and the perceived need to adapt to an emerging worldview no longer willing to accept papal claims to authority based solely on tradition. By the mid- eighteenth century only Piedmont and Naples, among the Italian states, had any real political and military clout in European dynastic dramas. The others had to rely on strategic alliances to preserve their independence. Because the Papal States remained neutral in conflicts between Catholic princes, an attitude of appeasement and accommodation necessarily carried the day. Pontifical strategies based on cultural politics to bolster Rome’s position had been developing since the end of the seventeenth century, but Catholic reform to be carried out in conjunction with the secular rulers came later, reaching its apogee under Benedict XIV (r. 1740–58). It would be cynical to argue that the papal version of enlightened Catholicism was engendered only by fear and political impotence, although those were doubtless factors. Much more significant, however, were the legacy of reform begun at the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century and the formal rejection of papal nepotism in the bull issued by Innocent XII (r. 1691–1700) in 1692.

Tridentine reform and enlightened Catholicism shared many goals. Both were deeply concerned with eliminating simony in the awarding of Church offices, increasing the number and quality of seminaries that trained parish priests, deploying the arts to promote piety and provide visual models of sanctity, and enforcing canonical rules regarding episcopal residency. Catholic enlightenment reform, unlike its Tridentine predecessor, however, emphasized anti-nepotism, improvement of the working relationship with Catholic monarchs, and social rather than more strictly theological issues. Moreover, eighteenth-century ecclesiastical reform responded not so much to a Protestant challenge as to the need to secure the Church’s relevance. Appeals to culture, the arts, and history were more significant in the era of enlightenment than they had been in the Counter-Reformation.

Anyone who has been to Rome is cognizant of the historical legacy everywhere in evidence. Italians took (and still take) great pride in their position as the home of Western antiquity’s greatest empire, and the popes self-consciously claimed the mantle of imperial authority. While some felt that the weight of tradition had enervated the peninsula, others—like the economist, philosopher, and art historian Lione Pascoli (1674–1744)—looked to the past as a promise of future progress, claiming that “the world is still young and full of possibilities.” Pascoli and others began to understand the shifting nature of historical judgments—for example, the disparagement of the modern Italian school of painting—and predicted that in time artists such as Giovanni Battista Gaulli (1639–1709) and Carlo Maratti (1625–1713) would get their due. Catholic reform also drew inspiration from its venerable past, and those seeking reform viewed it not as the pursuit of a perpetually unattainable goal but as an active agent of change in contemporary efforts to create a better world.

Because many Catholic intellectuals embraced reform and posited a broad array of ideas for transforming the Church from within, some attention to the nuances of the adjective “moderate” is required to assess the remarkable accomplishments of these individuals. Two prominent figures help make my point: Celestino Galiani (1681–1753) and Lodovico Antonio Muratori, the recipient of the letter from Crespi quoted in the epigraph to this chapter. Galiani, one of Italy’s leading proponents of Newtonian thinking and empirical science, was also a papal diplomat and abbot general of the Celestine Order. Clement XII (r. 1730–40) named him bishop of Taranto in the kingdom of Naples, where he spent the last twenty years of his life. Galiani, with an unusually well developed understanding of the strong link between political authority and cultural reform, was in a key position, as the abbot of a major Catholic order and a trusted advisor to the king of Naples, to promote progressive ideas. In his best-known treatise, La scienza morale, he came as close to a Lockean privileging of human reason as was possible for a professed Catholic. (John Locke’s publications were all on the Holy Office’s Index of Forbidden Books by the time Galiani’s publication appeared.) The Celestine savant had also been influential as a teacher in Rome during the pontificate of Clement XI (r. 1700–1721), numbering among his pupils Silvio Valenti Gonzaga (1690–1756), who later became cardinal secretary of state under Benedict XIV. In tribute to his mentor, the gout-stricken cardinal journeyed to Naples to attend Galiani’s funeral in 1753, only three years before his own.

Compared with Galiani, who engaged with scientific progress and cultural reform, Muratori represented the more moderate cadre of Catholic reformers, emphasizing clerical discipline, institutional responsibility to society’s underclass, and a tireless war against the “excesses” of popular piety and superstition. Both thinkers believed that reform was essential to the survival of traditional institutions. Muratori, however, was more interested in empiricism’s implications for the study of history than in contemporary science. Arguably Settecento Italy’s most respected historian, Muratori, like his contemporary Pascoli, took great pride in Italian cultural achievements under the aegis of the Church. His Annali d’Italia, a twelve-volume study of post-antique Italian history, published in Milan from 1744 to 1749, is one of the discipline’s foundational texts. It is based on the new empirical methodology that looked to archival documentation, works of art, and cultural artifacts for “truth.” The Italian Annals is still an essential source for the study of Italian medievalism, but Muratori’s numerous publications on spiritual and ecclesiastical topics had a greater impact on enlightened Catholic thinking.

Muratori’s Concerning Christian Charity, so much admired by Crespi, argued that lay institutions, which in Protestant countries did the work of caring for the poor and sick, were not effective in Catholic countries. Instead, the traditional Catholic system of almsgiving, confraternities, hospitals run by monks and nuns, and other pious establishments should be renewed and expanded. To Muratori, the secular workhouse could only stockpile the poor, whereas combining spiritual direction with physical sustenance would produce better citizens and better Christians. A sustained renewal of charitable initiatives, moreover, would energize Catholic elites, promoting class harmony. A year before his death Muratori published Della pubblica felicità oggetto de’ buoni principi (Concerning public happiness as the object of good princes), the century’s most fully developed argument for enlightened social paternalism based on the principle of public charity directed by the elite under ecclesiastical leadership. Muratori’s arguments assumed a vital role for both church and state in the improvement of society; the notion that they should be separate, a central tenet of much enlightenment thinking, would never have occurred to him.

Although many of Muratori’s publications were controversial and provoked negative reactions among the ecclesiastical hierarchy’s more conservative and traditional circles, their profound impact is undeniable. This is especially true of his most intellectually developed spiritual work: “Da ‘Della regolata divozione’ de’ cristiani” (Concerning a well-regulated Christian devotion), published in 1747. Many have characterized this fairly short book as the most influential text of Catholic enlightenment. Its effect on contemporary thinking about religious observance, popular devotions, cults, the responsibilities of the bishops, and the proper role of parish priests cannot be overstated. Among Muratori’s numerous complaints about popular piety was the foregrounding of devotions to the saints (especially local ones) and the Virgin Mary at the expense of God the Father, Christ, and the Holy Spirit. Such practices were in his view remnants of ancient pagan superstitions. Ringing church bells to ward off storms and other natural disasters is a characteristic example of the “disorders” he condemned. Devotion to the saints should focus on the imitation of their virtues and not on their divine “powers.” He endorsed Mary’s special role as an intercessor but bluntly pointed out that she is not Christ. Grace is given only by the Holy Trinity and may be achieved with or without the Virgin’s help. The Muratorian ne plus ultra of Christian devotion may be summarized thus: “Jesus Christ, therefore, is the true and real hope of Christians.”

In 1740 Pope Benedict XIV published a book on the Sacrifice of the Mass, the central sacrament of the Roman Catholic Church in which communion bread becomes the living body of Christ. It conforms closely to Muratorian ideas. Formal restraint, adherence to the proper performance of the various rites and ceremonies, and, above all, standardization were essential. The utmost decorum was to be maintained at all times. This special emphasis on the visible aspects of Church ceremonies was especially important for the arts because liturgical vestments, instruments, altar decorations, and other objects were given greater prominence than ever. Benedict’s treatise was published in Latin, because priests and other clerics were the intended audience. It was part of a broader enlightened Catholic discourse on the history of the liturgy that ecclesiologists—Oratorian, Theatine, and Maurist—were investigating. To underscore the vital importance of the Mass to progressive Catholics, the Lambertini pontiff established an academy devoted to the liturgy in its historical context in the early months of his pontificate.

Included in the enlightened Catholic project of reform and spiritual renewal was the investigation of Church history, using the most advanced methodologies to purge the institution of unsubstantiated traditions, bogus hagiographies, and devotional abuses. Reform Catholicism sought to make faith “reasonable” and more socially responsible. Self-criticism carried out in a scholarly manner was essential to the process. Debunking pious legends and false martyrs, among other desiderata, had to be pursued rigorously. The Roman abate (a cleric in minor orders supported by an ecclesiastical stipend, in French abbé) and diarist, Francesco Valesio, reported on one of the more egregious legends of contemporary Catholicism in an entry dated July 27, 1732. He criticized the Discalced Carmelites of Santa Maria della Vittoria for joining their shod brethren for the first time to honor the prophet Elijah, traditionally believed to have established the Carmelite Order. Valesio condemned what he called a “nonsensical exercise” in support of “this fable.” Although Benedict XIV was also deeply skeptical, the traditional belief was allowed to stand. Indeed, the Carmelites employed the sculptor Agostino Cornacchini (1686–1754) to make a colossal statue of Elijah for their niche in Saint Peter’s as one of the series of “portraits” of the founders of the religious orders begun by Clement XI in 1702 (fig. 1).

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.