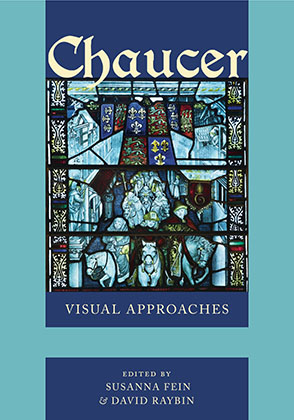

Chaucer

Visual Approaches

Edited by Susanna Fein and David Raybin

“Chaucer: Visual Approaches offers a diverse and stimulating set of essays that challenges its readers to consider anew Chaucer's way(s) of seeing his world and our way(s) of 'seeing' Chaucer. Professors Fein and Raybin, scholars of lively mind and commendable dedication to the service of their profession, have once again put Chaucerians in their debt by shepherding this innovative collection into print.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Basing their approach on contemporary understandings of interplay between text and image, the contributors examine a wealth of visual material, from medieval art and iconographical signs to interpretations of Chaucer rendered by contemporary artists. The result uncovers interdisciplinary potential that deepens and informs our understanding of Chaucer’s poetry in an age in which digitization makes available a wealth of facsimiles and other visual resources.

A learned assessment of imagery and Chaucer’s work that opens exciting new paths of scholarship, Chaucer: Visual Approaches will be welcomed by scholars of literature, art history, and medieval and early modern studies.

The contributors are Jessica Brantley, Joyce Coleman, Carolyn P. Collette, Alexandra Cook, Susanna Fein, Maidie Hilmo, Laura Kendrick, Ashby Kinch, David Raybin, Martha Rust, Sarah Stanbury, and Kathryn R. Vulić.

“Chaucer: Visual Approaches offers a diverse and stimulating set of essays that challenges its readers to consider anew Chaucer's way(s) of seeing his world and our way(s) of 'seeing' Chaucer. Professors Fein and Raybin, scholars of lively mind and commendable dedication to the service of their profession, have once again put Chaucerians in their debt by shepherding this innovative collection into print.”

“With arresting and beautiful illustrations and powerful explorations of ‘intervisuality’ by leading scholars, Chaucer: Visual Approaches is a welcome expansion of the way we see both Chaucer’s works and Chaucer’s world.”

“This richly illustrated new collection of essays demonstrates the great range of ways in which visual images are significant to Chaucer’s writings. Dealing with images drawn in words, evoked by words, and made by words on the page, the essays remind us of the scope for original work in this exciting area. The collection has illuminated for me some of the imaginative processes that take place as we read.”

“Susanna Fein and David Raybin, consummate Chaucerians, have drawn together one of the most compelling collections of essays I have seen on Chaucer in recent years. . . . Essay after essay, including each of their own, shapes a sparklingly original argument based on a wealth of visual material: the profusion of images, new arguments, and deeply researched manuscript observation offers insights on every page. We do not just read Chaucer freshly, we see his imagination at work and are sent back to his writing to rediscover its rich colors for ourselves.”

Susanna Fein and David Raybin are joint editors of The Chaucer Review and coeditors of Chaucer: Contemporary Approaches, also published by Penn State University Press. Fein is Professor of English at Kent State University, and Raybin is Distinguished Professor of English Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface . Chaucer: Visual Approaches / Susanna Fein and David Raybin

Acknowledgments

I. WAYS OF SEEING

1 Intervisual Texts, Intertextual Images: Chaucer and the Luttrell Psalter / Ashby Kinch

2 Creative Memory and Visual Image in Chaucer’s House of Fame / Alexandra Cook

3 “Quy la?”: The Counting-House, the Shipman’s Tale, and Architectural Interiors / Sarah

Stanbury

4 The Vernon Paternoster Diagram, Medieval Graphic Design, and the Parson’s Tale /

Kathryn Vulić

II. CHAUCERIAN IMAGESCAPES

5 Standing under the Cross in the Pardoner’s and Shipman’s Tales / Susanna Fein

6 Disfigured Drunkenness in Chaucer, Deschamps, and Medieval Visual Culture / Laura Kendrick

7 The Franklin’s Tale and the Sister Arts / Jessica Brantley

8 Miracle Windows and the Pilgrimage to Canterbury / David Raybin

III. CHAUCER ILLUSTRATED

9 Translating Iconography: Gower, Pearl, Chaucer, and the Rose / Joyce Coleman

10 “Qui bien ayme a tarde oblie”: Lemmata and Lists in the Parliament of Fowls /

Martha Rust

11 The Visual Semantics of Ellesmere: Gold, Artifice, and Audience / Maidie Hilmo

12 Drawing Out a Tale: Elizabeth Frink’s Etchings Illustrating Chaucer’s “Canterbury

Tales” / Carolyn P. Collette

Notes

Bibliography

Editors and Contributors

Index of Manuscripts

General Index

CHAPTER ONE

INTERVISUAL TEXTS, INTERTEXTUAL IMAGES: CHAUCER AND THE LUTTRELL PSALTER

Ashby Kinch

One of the most striking of English Gothic manuscripts, the Luttrell Psalter (London, British Library MS Additional 42130) consists of a calendar, the psalms and canticles, and a litany with collects, and the Office of the Dead. It is closely related in key stylistic traits and shared content with deluxe manuscripts from East Anglia—the Ormesby and Rutland Psalters—and from London workshops—the Smithfield Decretals and the Taymouth Hours. The Luttrell Psalter was produced in two campaigns by five different artists who occasionally worked in tandem. Only fourteen lines of text appear on each large page (360 × 245 millimeters), providing ample space for marginal illustrations, which appear on 200 of the 309 folios. The staggering scope of the marginal illustration was a conscious design principle, unique in its period. Due to the abundant scenes of daily life that appear in the margins, images culled from the Luttrell Psalter have been a mainstay of popular publications on the daily life of medieval England for over two centuries. Modern authors draw especially from the manuscript’s representations of games (e.g., fols. 157r, 158v, 159r, 161r), agricultural practices (fols. 170r–173v), and feast preparations (fols. 204r–208r). Students of Chaucer are familiar with scenes from the Luttrell Psalter, as reproductions of its marginal images regularly appear in books aiming to illustrate “Chaucer’s World,” even though work on the Luttrell Psalter was begun in the 1330s (before Chaucer was born) and abandoned by 1345.

This habit of decontextualizing medieval manuscript images (and the Luttrell Psalter is by no means unique in serving this illustrative function) obscures the complex conditions under which such a deluxe manuscript was produced, received, and transmitted. By contextualizing both the psalter itself, as well as its use and abuse in modern scholarship, Michael Camille’s Mirror in Parchment corrects some of the critical imbalances resulting from the “assumption that pictorial representations are an unmediated and direct expression of the ‘real.’” This tendency can be seen in even so astute a critic of the visual arts as V. A. Kolve, whose Chaucer and the Imagery of Narrative transformed the way Chaucerians look at images. At a key moment of definition, Kolve uses this very term—”unmediated”—to characterize the difference between Chaucer’s “narrative images” and what he terms “symbolic images.” The latter, he states, are “known from other medieval contexts, both literary and visual, where their meanings are stipulative and exact, unmediated by the ambiguities and particularities of fiction.” The idea of an “unmediated” image enables Kolve to approach visual material as static cultural evidence, which does not require sophisticated interpretation when placed alongside the “ambiguities and particularities” we so cherish in Chaucer. Indeed, in later work Kolve claimed that the Luttrell image of a carter on folio 173v “records medieval life free of transcendent system, fitted catch-as-catch-can into the uncommitted space of the manuscript’s borders” (Fig. 1.1). While the interpretive energy Kolve generates in his astute and penetrating readings of Chaucer justifies to some extent this neutralization, the Luttrell Psalter is neither “free of transcendent system” nor are its images “fitted catch-as-catch-can.” The manuscript is designed to showcase a particular transcendent system, chivalric power, as realized in the local English village context in which that power was manifest. Its images are thoroughly mediated by this context, as well as by the craft practices of medieval illustration that generate their own “particularities” or, in Paul Binski’s phrase, forms of “serious intelligence.”

<insert fig 1.1 around here>

As several decades of excellent scholarship on the Luttrell Psalter have revealed, the overlapping contexts of devotional reading, aristocratic display, and regional politics provide powerful tools by which to analyze the surprising and endlessly fascinating links among image, text, and the social and political world of pre-plague England. Despite its affiliation with contemporary illustrated devotional manuscripts, the Luttrell Psalter is an idiosyncratic production that catered to the tastes, interests, political aspirations, and anxieties of its patron, Sir Geoffrey Luttrell, who appears in a famous arming scene on folio 202v, beneath the caption “Dominus Galfridus Louterell me fieri fecit” (Lord Geoffrey Luttrell had me made) (Fig. 1.2). The magisterial execution of this image and a companion feast scene eleven folios later, on 208r (Fig. 1.3), have been the focus of recent scholarship because these scenes represent an ideology of lordship, providing insight into how a specific patron attempted to sacralize his lordship by means of imagery. These images suggest that he is both the divinely sanctioned dominus who realizes God’s plan for order in a chaotic world, and also a humble penitent who seeks comfort in an all-powerful God. The feast image realizes the correspondence between dominus and Dominus in a particularly effective way by echoing the form and design of a Last Supper image occurring in an earlier section of the manuscript (fol. 90v), here with Luttrell occupying the place of Christ. These images place Luttrell in the literal and symbolic center of a domestic ideology that links material, domestic, and spiritual economies. This conceptual subtext, built upon a key intervisual echo within the manuscript, loses its force when excerpted from the manuscript context, as in Roger Sherman Loomis’s A Mirror of Chaucer’s World, where he uses the feast image to illustrate the greed of friars.

<insert figs 1.2 and 1.3 around here>

The Luttrell Psalter, like many of its contemporary devotional manuscripts, is also designed to generate maximum cognitive effect. As Lucy Freeman Sandler has noted, images in psalters functioned

to provide a heightened and intensified experience of reading, through the discovery of all the riches both apparent and concealed in the words. If the words give rise to the images, the images disclose the depths of meaning in the text.

English Gothic manuscripts are distinguished from their Continental counterparts in part by the range and diversity of narrative material running through the margins, often in bas-de-page sequences that encourage readers to link images on consecutive pages, and thus to construct narrative structures that function independently of the text they illustrate. To read these images well requires not only the ability to develop connections between marginal images and the text on the page—a “vertical” relationship that places the text in a privileged position—but also to read “horizontally” for the relationships between and among manuscript images. Attending to this intervisual context provides some of the manuscript’s most interesting interpretive moments. These reading practices also bring literary and visual studies together through the concept of intervisuality, built upon an analogy with intertextuality. As Camille writes, intervisuality

means not only that viewers seeing an image recollect others which are similar to it, and reconfigure its meaning in its new context according to its variance, but also that in the process of production one image often generates another by purely visual association.

This sense of the complex relationship between text and image in marginal imagery (as well as between image and image) has resulted in a shift of critical attention away from the sociological model of the margin (based on the metaphorical mapping of “center” and “periphery” onto the manuscript page) to a perceptual or cognitive model (based on the kinds of reading and thinking induced by marginal imagery). Recent essays by Laura Kendrick and Binski have argued that the sociological theory of the margin has its roots in modernist aesthetics, which unnecessarily forecloses some of the dynamic interplay between and among images throughout the manuscript page, which is better explained by means of concepts like varietas drawn from medieval aesthetic practice. An open approach to the margins also accounts well for the fact that not all of the so-called “marginal” material is morally coded as “outside.” In addition to the grotesques and babewyns that draw our attention, much of the marginal imagery in the Luttrell Psalter belongs to conventional religious narratives. There are, for example, an extended sequence of saints (fols. 29r–60v, 104r–108v); a Life of Christ (fols. 86r–96v); and scenes from the Life of the Virgin, including miracles (fols. 97r–105r). And some of its most powerful marginal imagery clearly belongs to the positive self-assertion of its patron as a figure of both political power and devotional humility. Kathryn Smith has argued recently that the cognitive engagement of the reader with the manuscript page begins at the margin, which constructs the “zone of the page most intimately connected to the body of the reader/viewer” and thus offers a “frame that structures the apprehension of its contents and the filter through which they are viewed.”

This new approach to the manuscript margin as a frame provides an important conceptual analogue that facilitates a comparison of manuscript art to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Building on the pioneering insights of Elizabeth Salter nearly fifty years ago, Kendrick has developed the most sustained case to date that Chaucer may have derived aesthetic principles from the margins of illustrated devotional books. She argues, in particular, that Chaucer may have found there the idea of linking material so as to develop a running gloss on central textual matter, which becomes, in essence, an “interludic” space that comments on the text. We can assume that Chaucer’s social station and personal investment in books provided him with access to a wide array of contemporary, recent, and older illustrated books. Many such books would have been products of artists and workshops in Paris and Bruges, or books he saw on his trips to Italy. But Chaucer would have found in fourteenth-century English book illustration ample, interartistic analogues for the technique of playing out ideas through his frame material, which requires the reader to connect ideas found in a separate cognitive spaces, similar to the margins and core of the manuscript page. We cannot know, of course, whether Chaucer ever saw the Luttrell Psalter—likely, he did not. But I argue here that a sophisticated analysis of the aims, practices, and shared motifs of Chaucer and the artists of the Luttrell Psalter can enrich our understanding of the multimodal aesthetic practices of late medieval visual art and literature. While Chaucerians have tended to approach illustrated manuscripts as an abstract category from which to derive broad Gothic aesthetic principles, I think there is more critical traction to be gained by close scrutiny of a single manuscript like the Luttrell Psalter, seeing it as a close analogue for a literary artist like Chaucer, because it can be approached as a complex work of art with integral design principles.

This chapter aims to demonstrate that a focus on the Luttrell Psalter as a mediating agent rather than a simple “mirror” reveals an imagetext that engages its reader in sophisticated intervisual play analogous to the complex mediations Chaucer performs in the Canterbury Tales. I do not give interpretive priority to the text over the image, or vice versa, but approach both as “composite arts,” in W. J. T. Mitchell’s phrase, based on the assumption that “all media are mixed media, combining different codes, discursive conventions, channels, sensory and cognitive modes.” We have to challenge ourselves continuously to think of text and image as intrinsically linked—that is, as cognitive doubles of one another—in order to avoid the problem of neutralizing the image in favor of the text, or vice versa. Despite the fact that literary and visual objects are of equivalent value in most current theoretical models of visual study, scholars tend in practice to view one as the privileged site of interpretation, with the other becoming static evidence of a common culture, not subject to developed interpretation. In the first part of this chapter, I will demonstrate this point by highlighting instances where greater attention to the comparative object opens the two imagetexts to fuller understanding, particularly by recognizing the sophisticated ways in which both Chaucer and the artists of the Luttrell Psalter engage in highly mediated play with the boundaries of their aesthetic projects. In the second part, I turn to historical context as a means to conduct a critical examination of chivalric identity as represented in the Luttrell Psalter through an intervisual analysis of the repeated appearance of the Luttrell arms in the manuscript. The psalter’s representation of chivalric identity links it with the historical Chaucer through his testimony in the infamous Scrope-Grosvenor case in the Court of Chivalry. This under-utilized episode from Chaucer’s biography demonstrates the entanglement of Chaucer and the Luttrell Psalter in a broader visual culture whose forms merit further study.

In his reading of The Friar’s Tale, Kolve argues counterintuitively for the carter as a key narrative image, a place where the marginal figure suddenly becomes central to the meaning of the story by crystallizing the idea of the “man in the middle.” To illustrate the common tradition of the carter, Kolve extracts an image from the Luttrell Psalter (Fig. 1.1), about which he writes,

A steep hill is to be inferred. All available energy and attention, from man and beast alike, is concentrated on that task. The picture bears no discernible relation to the psalm text around which it moves, and it invokes no moral or theological context.

While Kolve is right that the image does not invoke an immediate moral context, nor a direct relationship to the text on this particular page, this image is the culminating moment of an important cycle of images of agricultural labor that have to be read narratively across the bas-de-page of consecutive folios, in which sowing, reaping, harvesting, and finally transporting the crop are depicted (fols. 170v–173v). All of these images flow from left to right, providing a key visual marker of narrative progress until we arrive at the carter, who drives his cart from right to left. And if we look with our eyes and not our abstractions, we see there is no hill in the image, inferred or otherwise: one nineteenth-century reproduction goes so far as to add a line to this image in order to make it “realistic.” But the image can be better explained as a visual joke on the limits of the page: the horses rear up because they have hit the margin of the book. This self-conscious attention to the limits of design is enhanced by our attention to the other page of the opening (fol. 174r), which has a radically different mise-en-page, with a heavy ornamental border and an illuminated initial, because Psalm 97 marks a conventional division in psalter texts. The artist reverses the direction of the carter on the prior page in order to signal overtly the precise point where a limit is imposed by the design of the book itself. The idea of working against the limitation of space and design plays out in a number of images in this section of the manuscript, where the artist develops a metacommentary on the design constraints created by the prior border campaign. Indeed, the concept of spatial constraint becomes a visual theme throughout: fillers that occur on almost every page often show figures who are squeezed into the available space and whose animal bodies push against these constraints. Laborers in a bas-de-page on folio 172v (Fig. 1.4) confront the invasion of their workspace by the foliate vines that descend from line fillers, which were completed prior to the marginal illustrations in a separate campaign. One woman drops her scythe as she bends back in surprise, her eyes angled up at the foliation. On the other side of this opening, on folio 173r (Fig. 1.5), men are stacking sheaves of wheat, the topmost laborer looking up as he realizes that a piece of descending foliage blocks his upward progress. The constraints of the design sequence, including its clash of styles, are converted into elegant moments of bravura where art confronts the limits imposed on it both by social reality and artistic constraint.

<insert figs 1.4 and 1.5 around here, opposite one another>

This visual play with the materials and processes of art emphasizes precisely what Kolve denies, namely, the mediating consciousness of the artists, who attend in full awareness to the new world created in the margins. The book might “mirror” the interests of Sir Geoffrey Luttrell, who exerts his authority over a working feudal estate, but it also highlights the artificiality of the representation and thus draws direct attention to the mediating labor of the artists. The Luttrell artists produce what amounts to a new artistic ecology, which they manipulate to great effect, providing a doubled world that occupies the middle space between social reality and artistic imagination. Foliate borders grow into polymorphic babewyns, who double their human counterparts by incorporating humanoid features, as well as doubling themselves in the forms of twinned heads emerging from common bodies, mirror bodies attached to a common head, and a number of other variants that display a fascination with the visual motif of duplication and difference (see fols. 84r, 187v, 188r, 191r, among many others). Horses balance on tenuous vines, their feet resting on two slightly different horizontal planes (fol. 159r) or on the backs of babewyns (fol. 41r). The aesthetic self-consciousness, which draws readerly attention to the shifting relationships between verbal and visual forms, enhances the devotional subject’s reading of the psalter text by creating a conceptual interface that maximizes cognitive engagement. Working from this premise, scholars have discovered dozens of word-image puns—broadly known as imagines verborum—in the Luttrell Psalter, whereby the text of the psalms is abstracted into component words and phonemes, which generate secondary meanings that are reworked by the images (often ironically) to refer to novel and unexpected scenarios. These imagines verborum are now subject to multiple modern interpretations based on the accepted principle that an image might mean more than what it “says” on the visual surface. We are reminded constantly that the text is always mediated by the visual engagement of the reader with the page.

Such meta-artistic play, which draws special attention to the conditions of artistic creation, is a given for most readers of Chaucer, a writer who regularly foregrounds the boundary between fiction and reality as part of an overall strategy to complicate a reader’s unfiltered sense of his literary world. We could hardly read the Canterbury Tales without this concept, which is crucial to its generative ironies and to Chaucer’s practice of engaging tough contemporary cultural problems within the safe space of literary play. When we recognize that some of this same mediating work is being done in the Luttrell Psalter and its contemporary manuscripts, we have a broader context for understanding the ability of Chaucer’s audience to engage with his navigation of the boundaries between source and retelling; text and voice; and narrative and social agents (including the reader). Chaucer’s writing is, right from the beginning, both hybrid and intensely self-conscious of its status as a mediated object, shot through with the writing of others, with which he ambivalently grappled. He directly involves his readers in that process by reminding them of their part in the mediating process.

Awareness of the layered mediation of Chaucer’s writing heightens our critical attention to his appearance as an intertextual reference in Camille’s book-length study, where Chaucer plays roughly the same role that the Luttrell Psalter plays for Kolve: a body of neutral, cultural evidence free of mediating context. For example, the Luttrell Psalter contains a comic image of an ape riding a goat while holding an owl on his arm (fol. 38v), parodically imitating images of knights hunting with falcons that are often depicted in marginal art, including that of Luttrell itself (fol. 41r). Camille’s fascinating discussion of the image stresses its relationship with a distinctive English aphorism, “Pay me no lasse than an ape and an oule and an ase,” which appears in a Latin register of legal writs beneath a similar image (an ass is substituted for the goat). Chaucerians might recall that the phrase “of owles and of apes” appears in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale (VII 3092), which Beryl Rowland first glossed by pointing to the pejorative connotations of both animals in marginal imagery, including the Luttrell image. For Camille, Chaucer is merely a witness to the association of this image with the irrational: “A juxtaposition of such elements meant something irrational—‘owls and apes’ in Chaucer’s words.” But to call these “Chaucer’s words” is more than a little misleading: the narrative context, which is always paramount in Chaucer, is a highly “embedded” quotation. Chauntecleer’s debate with Pertelote about the significance of dreams leads him to list examples of dreams that had prophetic significance, including a man who refuses the cautionary warning of a friend’s dream and proceeds with a planned sea journey that results in his death. It is not Chaucer, but this unnamed rationalist, cited as an authority by a talking rooster in an argument with his best-loved chicken, who rejects the significance of (seemingly) absurd dreams. Whatever Chaucer might have thought about “owls and apes” (or asses for that matter), the intervisual circuit that runs through English visual culture links the Luttrell Psalter and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in an open inquiry about the value of the absurd image. Both instances of this image are part of a verbal-visual dreamspace in which a reader is expected to expend cognitive energy. If it is true that “Men dreme of thyng that nevere was ne shal” (VII 3094), it is also true that such dreams can be engines of creativity, as Chaucer’s earliest poetry attests. By no means is this context-dependent reference to “owls and apes” a simple statement on the “irrational,” but an open invitation to follow the dizzying turns of interpretation that precede and follow.

The concept of mediation is also at stake in Camille’s citation of a passage from the Franklin’s Tale during a discussion of the Luttrell Psalter’s Castle of Love image (fol. 75v). Camille places the image in the context of “fantasy battles” performed at court, “the kinds of fantasies described in Chaucer’s ‘Franklin’s Tale’ in more positive terms as the work of ‘tregetours’ or magicians.” Whether the image is “positive” depends, of course, on one’s take on the Franklin’s Tale’s outcome, since the “magyk natureel” (V 1125) that drives the plot is far from unambiguously good. The reference to tregetoures appears in Aurelius’s brother’s speech, as he, distraught at his brother’s lovesickness, seeks a remedy. That process begins with the narrator exploring the brother’s inner thoughts as he conducts an almost desperate search “in remembraunce” (V 1117)—necessarily patchy—of his time in Orléans, where “a book he say / Of magyk natureel” (V 1124–25). But Chaucer habitually complicates textual reception, so we immediately discover that the book was not his, but belonged to his felawe, who, as it happens, should not have been reading it all since he was studying law. And, of course, the brother is not given the book, but steals a glance when his felawe is away, as he “Hadde [it] prively upon his desk ylaft” (V 1128). The reader’s realization of the brother’s highly vitiated knowledge frames our response to his “remembraunce” of the work of tregetoures, this time mediated from oral transmission, not personal experience (“have I wel herd seye”; V 1142). Chaucer goes out of his way to indicate that this man’s confidence—

“I am siker that ther be sciences

By whiche men make diverse apparences,

Swiche as thise subtile tregetoures pleye”

(V 1139–41)—

is not well justified: he overlooks all of the contexts that mediate his partial and fragmentary knowledge. And everywhere in the Canterbury Tales where such naive engagement with texts takes place, we are alerted to the moral or social dangers of bad reading. For Camille, the narrative context of both the story and the larger project evaporates, replaced by a notion of Chaucer’s “reportage” of courtly games. The visual culture that links Chaucer with these tregetoures does not adequately convey the nuance of the passage’s fascinating reflection on the perils of mediated knowledge without further interpretation.

The Luttrell Psalter’s Castle of Love image is, in turn, enriched by this more complex view of Chaucer’s own mediating practices, as it triggers a range of associations with the dialectic between secular and religious forms of self-understanding—understandings that are woven into many contemporary illustrated manuscripts to which the Luttrell Psalter is related, including the Queen Mary Psalter, the Smithfield Decretals, and the Taymouth Hours. Smith has recently made a convincing case that the inclusion of the secular image-cycles of Beves of Hampton and Guy of Warwick in the bas-de-page of the Taymouth Hours is predicated on “the complex interplay of courtly, chivalric, devotional, and penitential themes in this pictorial-textual ensemble.” The Luttrell Psalter similarly relies on a reader being able to move nimbly among different frames of reference. One opening that performs this work quite explicitly makes a provocative connection between daily life and an image of popular sanctity. The reader attending to links between images in the ¬bas-de-page of folios 60v–61r naturally connects the display of Saint Francis’s stigmata with the image of bloodletting across the book gutter (Figs. 1.6, 1.7). While imitation of the saints could take extreme forms in medieval culture, this image provocatively suggests that the medical act of opening one’s veins has a sacral character that links us with Francis, and, indirectly, with the wounds of Christ. Is the sacral aura of the stigmata reduced by the comparison? Perhaps, perhaps not, but the cognitive work triggered by the juxtaposition functions to stimulate a devotional self-reflection that the image of Francis on his own might not. Imitatio Christi is displaced from the unapproachable sacred realm into the lived social life of the devotional reader.

<insert figs 1.6 and 1.7 around here, opposite one another>

Becoming attuned to the intervisual dialogue of the manuscript provides new interpretations of individual images while also generating a pattern of thinking analogous to the Canterbury Tales that accumulates new concepts as it advances. A well-known image on folio 60r, of a woman beating her kneeling husband with a distaff, occurs, for example, in a sequence of images of martyrs (fols. 29r–60v). Taken out of context, the image is a simple misogynist joke, not unlike the contemporary images of domestic inversion from misericords, for example. But, in context, this Luttrell image parodies a specific sequence of martyrs executed by sword, which includes Saint Thomas Becket, Saint John the Baptist, and, later, Saint Bartholomew (fols. 51r, 53r, 108r). And before we arrive at the wife beating her husband, we encounter another variation: a kneeling figure appears with a cut already on his neck and the name “Lancastres” written in a contemporary hand beneath the sword, which is wielded by the executioner (fol. 56r). The image refers to the execution of Thomas, earl of Lancaster at Pontrefact Castle in 1322, where it took several blows to sever his head. As a key member of the baronial opposition to Edward II, Thomas of Lancaster’s death quickly led to attempts to canonize him. Clearly, his appearance here among martyred saints is meant to affirm his significance as a “second Becket” and thus connects Sir Geoffrey Luttrell to the disaffected nobility who rebelled against Edward II. This highly mediated image adopts the iconography of martyrdom to bolster a particular political identity in a vexed environment of conflicting loyalties, as mid-level aristocrats like Luttrell anxiously considered their relation to the monarchy, and thus their conventional notions of chivalry, founded on the tension between self-assertion and submission. The text of the psalms regularly adopts the position of submission to the all-powerful Lord, and the devotional reader is encouraged to reflect on that model in his own social life. That submission is ironized by the text from Vulgate Psalm 31 (a penitential psalm), verse 4, which appears just adjacent to the image of the woman beating her husband: “For day and night thy hand was heavy upon me” (“Quoniam die ac nocte gravata est super me manus tua”). The image constructs the angry wife as a domestic analogue of an all-powerful God, but the joke only registers because forms of real vulnerability are acutely manifest in the other martyr images. The visual typology of martyrdom thus moves across several conceptual domains—spiritual, political, domestic—generating an intensive reflection on modes of male vulnerability, particularly concentrated on the vexing question of chivalric male identity forming and justifying itself under the threat of violence.

Chaucerians may well “hear” in this image an echo of the Monk’s Prologue, in which Harry Bailly complains about the way his wife Goodlief tongue-lashes him, culminating in a mock-monologue in her voice that ends, “By corpus bones, I wol have thy knyf. / And thou shalt have my distaf and go spynne!” (VII 1906–7). The fit of image to text is not perfect, but yet close enough to have rung a bell with Camille, who cites the couplet without interpretive comment. Whether or not Chaucer knew this image or an image like it—or, indeed, drew the entire idea from a textual convention—what these images create is a circuit of meaning running through the Luttrell Psalter and Chaucer’s text, a circuit that links artists with sophisticated tools at their disposal for drawing out a subtle set of ironies. While we may be reluctant to assume that the artists of the Luttrell Psalter, working for a powerful patron, had the leeway afforded by an author as crafty as contemporary scholarship imagines Chaucer to be, we need the salutary reminder that part of the work devotional books were meant to accomplish is a humbling submission to God in the recognition of one’s sin. Based on her work on early fourteenth-century devotional books, Smith has called for further attention to the way that marginal images might force us to theorize “a more variegated late medieval noble subjectivity,” which must of necessity include a recognition that such subjectivity is constructed in and through conflicts in identity, not simply through affirmations.

Such conflicts appear even in the most assertive images of self-presentation like the famous arming scene. For readers of medieval romance, the scene appears familiar, evoking the ancient topos of the mounted warrior heading off on a quest. The image is, however, highly unusual in devotional books and has been largely explained as an attempt by Sir Geoffrey, well past his military prime, to assert his lordship in a period of anxiety. His marriage to his wife Agnes Sutton, depicted here handing him his helmet, fell under scrutiny because it violated the acceptable degrees of consanguinity and threatened to invalidate any offspring of his son’s marriage to Beatrice Scrope, depicted here handing him his shield. His dynastic ambitions are literally written on the bodies of the two women. Agnes Sutton’s dress is blazoned with the arms of both the Luttrell family and the Suttons (whose arms also appear on fol. 41r on a gilded shield beneath a gilded helm with a fanned crest). Beatrice Scrope’s dress is similarly blazoned with the Luttrell arms and the Scrope arms, appearing here and in the margin above a bear-baiting scene (fol. 161r). Heraldic insignia circulate social identities and, along with them, social histories of alliances between families. But the elision of Sir Geoffrey’s son Andrew from the arming scene in favor of a focus on the women—who translate the abstract notion of heraldry in embodied form through children—reveals how masculine chivalric identity depends on female bodies.

With the benefit of historical distance, we can see that such anxieties, far from isolated, were endemic to the culture of chivalry in late medieval England and form a social infratext for both the Luttrell Psalter and Chaucer’s own engagement with what Lee Patterson called the “crisis of chivalry.” Patterson’s reading of Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale includes a pointed examination of an infamous case of the lengths to which knights went to defend the most obvious instance of their symbolic knighthood: their arms. The Scrope-Grosvenor case, which dragged on for six years (1385–91) and led to 450 depositions, brings Chaucer and the Luttrell Psalter into conversation with one another and highlights a fascinating intervisual narrative in the Luttrell Psalter. Chaucer gave testimony in the case in 1386, as did Andrew Luttrell, age 70, son of Sir Geoffrey, and both did so in favor of Richard Scrope, who won the case in 1390. But the case was not definitively settled until there was an unusual meeting of the baronial peers at which Robert Grosvenor was obliged to recite an agreement in which he abjured any statement in prior depositions impugning Scrope’s honor. Patterson’s discussion centers on “not just the highly public, ceremonial nature of the honor exchanges that constituted chivalric culture but the wholly social, even material sense of selfhood that it presupposed.” The anxiety of losing control of one’s heraldic identity is foregrounded in the Scrope-Grosvenor case because, as Patterson points out, “noble identity depends upon a system of signification . . . that is always open to misuse.”

As it happens, the Luttrell Psalter provides a fascinating narrative of such “misuse” of the Luttrell arms, which appear four times in the manuscript before their grand appearance on folio 202v and, again, in the feast scene on folio 208r. Taken together, these six instances provide a narrative focused on the fracturing of chivalric identity in the dispersal of arms through surrogates before they are recombined in the person of Sir Geoffrey. On folio 59r, they appear in their smallest form on a pennon attached to a trumpet, seeming to be almost a visual afterthought. On folio 157r (Fig. 1.8), a servant bearing a larger pennant with the Luttrell arms—the first step in an amplification of their visual significance—leans forward in pursuit of a cross-legged figure with bellows on his head holding a helmet. This latter figure, who appears in the manuscript in other guises, is a trickster, his crossed legs suggesting a mockery of the poor servant who desires to recapture his lord’s helmet, which has escaped his possession. On folio 163r, the arms appear on a hybrid, who dons a helmet, as though the helmet had remained in the marginal world because the trickster had passed it along to him. On folio 171r, a shield with the Luttrell arms held by a man sitting atop a bird appears alongside Vulgate Psalm 94, which Ellen Rentz astutely points out was read daily as the standard invitatory psalm.

<insert fig 1.8 around here>

All of this intervisual context, with the Luttrell arms scattered through the margins and out of Sir Geoffrey’s control, serves as preface for the synthetic image in which Luttrell himself appears astride his charger (Fig. 1.2). The overdetermination of the arms in this image suggests that he doth protest too much: his insignia appear on his helmet, pennon, pauldron, surcoat, saddle, horse’s embroidered surcoat, shield, and headpiece, as well as on the dresses of the two women. Smith notes that, while this image is the only framed miniature in the manuscript, it arises not from the center but from the margin, where it joins the sequence of arms that runs through the bas-de-page. In this image all of the various parts of the knightly assemblage that we have seen dispersed throughout the manuscript are reunited in a coherent, stable whole, represented in its most magisterial form. This image does powerful ideological work, suggesting that Sir Geoffrey’s chivalric splendor exerts centrifugal force, drawing his heraldic signs back to him despite their dispersal. This narrative possesses a coda, however, in the feast image, which conveys an important resonance with the psalter text that has so far escaped notice: it appears beneath Vulgate Psalm 114, “Dilexi quoniam exaudiet Dominus” (I have loved because the Lord will hear [the voice of my prayer]), the opening words of the Office of the Dead. This is not an accident. As the only part of the Church liturgy exactly reproduced in devotional books, the Office of the Dead was central to aristocratic devotional practices. Because of a deep cultural association of the Office of the Dead with the commemoration of ancestry, heraldic insignia often appear alongside the lead image —a highly legible placement adhering to an aristocratic ideology that viewed the transmission of arms as (in D. Vance Smith’s phrase) a form of “mortuary stockpiling.” The Luttrell Master utilizes the space behind the feast scene as a tableau in which the arms appear as a tapestry hung above the table, providing a symbolic link between Sir Geoffrey and his ancestors, on whose behalf he prays the Office of the Dead that advances their souls, even as he hopes for future progeny who will do the same. Luxury manuscripts call for visual attention, which can be converted into salvational coin in the devotional economy of late medieval culture. The presentation miniature and the feast scene thus stand as ideological bookends in which two faces of chivalric self-presentation—martial power and religious sanctity—are placed amid images of violence, dangerous and disruptive play, and a profusion of polymorphic forms that suggest a world exceeding its boundaries.

The Luttrell Psalter participated in a broad visual culture where heraldry penetrated into daily life in a wide variety of forms—from livery, to donor plaques in parish churches, to the arms hung above the residences and businesses of the muddled class of gentry who occupied London, which was Chaucer’s home for most of his life. Visual culture is not a lens that Chaucerians have utilized in their thinking about Chaucer’s testimony in the Scrope-Grosvenor case, but the poet’s engagement with his visual world is tied directly to the unique quality that Patterson observes in Chaucer’s deposition: “its urban setting, its circumstantial detail, and especially its narrative form.” In a passage that links him as a “witness” to the Luttrell Psalter through the mediating image of the Scrope arms, Chaucer traces an urban itinerary through Fridaystreet—which was near his home and thus, presumably, a familiar visual landscape—where his eyes alight on a “nouvelle signe” hanging above an inn. What is “nouvelle” is not the arms, with which he is familiar, but the “signe” hung in a place where he had not seen one before. The novelty here is a visual attraction breeding curiosity, generating a discussion with an unnamed person about the inn with the (presumed) Scrope arms. The cognitive dissonance that the encounter triggers for Chaucer mirrors Patterson’s sense of Scrope’s own crisis: a single set of arms should not refer to two people. When Chaucer discovers that the arms were “painted for Robert Grosvenor” and not Scrope—with the key word “depeyntez” repeated twice in the passage—we are reminded that heraldry requires a representational process (painting) and a medium (a body, place, or sign), which in turn mediates its social meaning. This “double” sign in turn triggers Chaucer’s own affective memory of his experience in battle at Rheims, twenty-seven years prior, where he first saw the Scrope arms amid the blazing heraldry of battle, at a time of somatic intensity certain to register in his memory. Heraldic signs do powerful work for this “experiencing subject” (in Patterson’s phrase), a circuit through whom the sign passes from battlefield to memory to present experience: “Geffray Chaucere esquier del age de xl ans et plus,” our forty-something poet who happens to be launching the Canterbury Tales.

The way in which the Luttrell Psalter and Chaucer talk to one another through an heraldic emblem provides an illustrative instance of the rich entangling of images and texts in the fourteenth century, a period of great artistic innovation. When image and text are grafted together, by the work of either culture or scholarship, they change form and become intermediated in ways that require new reading procedures. Further research comparing Chaucer’s literary production with aesthetic principles from manuscript illumination will enhance our understanding of his multimodal composition process, just as the rich tradition of scholarship on Chaucer’s literary experiment promises to deepen our understanding of the Luttrell Psalter. We will have understood British Library MS Additional 42130 only when we have fully parsed the elusive “me” in the caption of the book’s most famous image: “Dominus Galfridus Louterell me fieri fecit.” This “me” disconnects the book (as speaker) from the artist (as maker), diverting attention toward its patron, who is nonetheless “present” in the image only through the mediating brilliance of an implied artist. It is a profoundly Chaucerian moment, which is to say a moment of artful hide-and-seek that we have come to consider quintessentially Chaucerian.

NOTES

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.