The Warsaw Ghetto in American Art and Culture

Samantha Baskind

“This vivid approach to an important event will be appreciated by students and scholars of the Holocaust as well as general readers.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

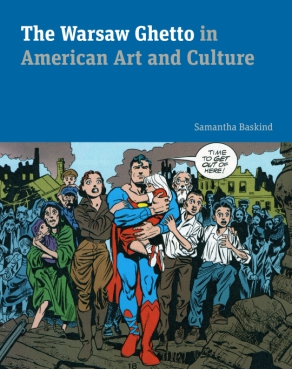

Samantha Baskind explores seventy years’ worth of artistic representations of the ghetto and revolt to understand why they became and remain touchstones in the American mind. Her study includes

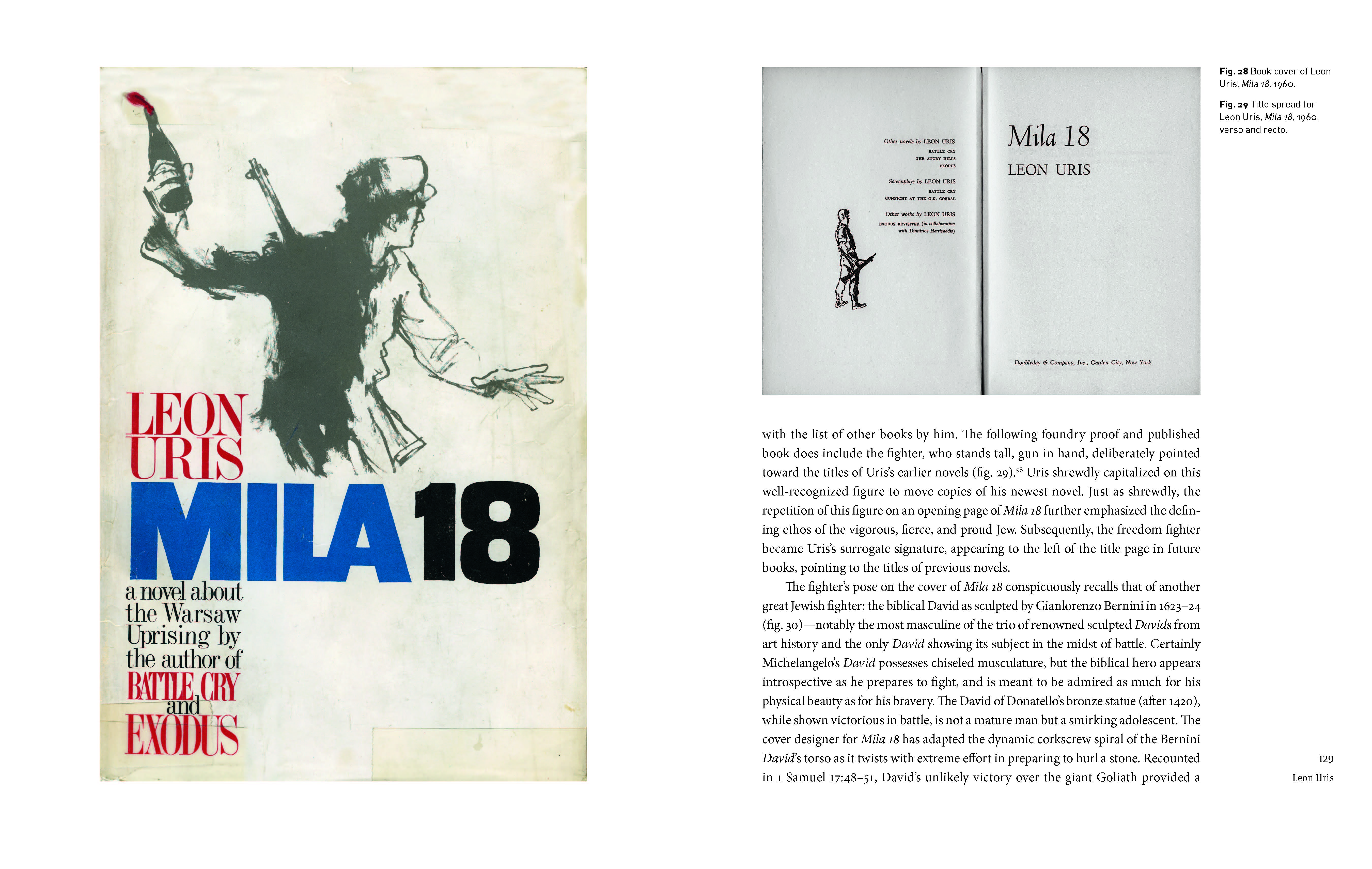

iconic works such as Leon Uris’s best-selling novel Mila 18, Roman Polanski’s Academy Award–winning film The Pianist, and Rod Serling’s teleplay In the Presence of Mine Enemies, as well as accounts in the American Jewish Yearbook and the New York Times, the art of Samuel Bak and Arthur Szyk, and the poetry of Yala Korwin and Charles Reznikoff. In probing these works, Baskind pursues key questions of Jewish identity: What links artistic representations of the ghetto to the Jewish diaspora? How is art politicized or depoliticized? Why have Americans made such a strong cultural claim on the uprising?Vibrantly illustrated and vividly told,

The Warsaw Ghetto in American Art and Culture shows the importance of the ghetto as a site of memory and creative struggle and reveals how this seminal event and locale served as a staging ground for the forging of Jewish American identity.“This vivid approach to an important event will be appreciated by students and scholars of the Holocaust as well as general readers.”

“As she painstakingly draws the map of American culture produced against the backdrop of the Warsaw Ghetto, Baskind analyzes the broader contours that all the individual projects in various media reveal in tandem about this corner of the American art scene. . . . . Baskind has produced a daring work of scholarship on American art.”

“A profound, broad-ranging, multimedia analysis of American responses to the armed Jewish uprising against the Nazis in Warsaw. . . . Baskind provides insightful interpretation grounded in meticulous research and supported by detailed, elegant, and illuminating visual analysis.”

“Her open and nonjudgmental treatment of many different artists who have depicted the ghetto over the past seventy years is a welcome addition to the historical discussion of the Holocaust in American culture. Future scholars should build on this book’s success, adding to Baskind’s wide-ranging guide to American art and literature on the Warsaw Ghetto with more historical consideration and discussion.”

“The Warsaw Ghetto uprising has long captured the imagination of novelists, poets, and artists. Samantha Baskind's wide-ranging and highly original study of the uprising's impact on American art and culture is a major contribution to our understanding of Holocaust memory.”

“In her penetrating exploration of how the Warsaw Ghetto has been represented in American culture over a seventy-year arc, Samantha Baskind reveals the ever-evolving significance of the ghetto and its uprising in real political and aesthetic time. With grace, a keen eye, and deep insight, she traces how new and changing media shape and reshape these events for contemporary audiences. Brilliantly illustrated, this is an excellent contribution to discussions of ‘the Americanization of the Holocaust’ and the Holocaust in visual culture—highly and warmly recommended!”

“[An] admirably readable account.”

“The Warsaw Ghetto uprising has resonated for more than seven decades with American Jews, looming in their consciousness ever since those wrenching days of April 1943. In spoken words, graphic images, and dramatic presentations it has played a powerful role in how they communicate among themselves about the great catastrophe of the Nazi era and how they present that cataclysm to the larger American public. A singular contribution, Samantha Baskind's book deftly and richly links the uprising to the inner politics of American Jewry and to its complex engagements with U.S. politics more broadly.”

“Baskind’s book is a tour de force: eloquent, wide-ranging, and engaging. This is important work, taking up a necessary challenge to document the cultural representations and refractions of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising over more than seventy years, showing it to be a rolling marker of postwar Jewish American identity.”

“Baskind creates a midrashic exploration of the ongoing story of the uprising, its relevance to future generations, and the ways in which it has come to inform Jewish cultural identity.”

Samantha Baskind is Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University and author of Jewish Artists and the Bible in Twentieth-Century America, also published by Penn State University Press.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. “You Must Be Prepared to Resist, Not Give Yourselves Up like Sheep to Slaughter”: Heroism, the Muscular Jew, and the Warsaw Ghetto, 1943–1950

2. “I Was Responsible to the People Who Had Played Out That Terrible Hour in History”: Rod Serling, Millard Lampell, and Familial Conflict Behind the Walls

3. “I Am a Jew and What Am I Going to Do About It”: Leon Uris, Mila 18, and Muscular Judaism

4. “I Would Like to Paint One Million Jewish Icons”: Samuel Bak’s Painted Memorials and the Traumatic Loss of the Youngest Generation

5. “Our Children, Our Children Must Live”: Joe Kubert, Comics, and the Saving Remnant

Epilogue: “Will the World Know of Us? Will the World Know?”: The Warsaw Ghetto in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Notes

Bibliography

Index

From the Introduction

On Passover eve, April 19, 1943, Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto mounted the now- legendary revolt against their Nazi oppressors. Modest numbers and meager weapons notwithstanding, a small group of Jewish militants held off two thousand well-armed SS men for twenty-eight days, even though the entire Polish Army had fallen to the Nazis in a comparable amount of time after the blitzkrieg invasion of September 1, 1939. From that fateful day until the current moment, the courageous actions of the partisans who resisted during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising—along with the preceding deprivation and despair of ghetto life—have captured the American imagination. To be sure, this central locale and its seminal culminating affair have metamorphosed into a potent emblem of the war and Jewish life in Europe that is nearly as prominent as Auschwitz. If the Holocaust is known as unqualified evil, with Auschwitz serving as a synecdoche, then the Warsaw Ghetto serves simultaneously as the epitome of courage and the ultimate in squalor. This book explores these two leitmotifs, among others, inherent in many projects about the Warsaw Ghetto. The range of evocative material newly exposed measures more precisely than before exactly how, over generations, the ghetto has been staged by American artists. Paying close attention to the ghetto’s varied meanings in American life, I investigate how its story has been told, retold, and remembered across creative boundaries, including fine art, book illustration, film, television, radio, theater, fiction, poetry, and comics.

The structure of this study is mostly chronological, arranged also for thematic coherence. Five chapters examine different artistic “versions” of the Warsaw Ghetto, stressing the various ways representations, cutting across seven decades, have conveyed the agenda of a particular moment, in part by interrogating how we know and depict the past. While analyzing what diverse cultural conceptions reveal about how Americans remember the ghetto, and by extension the Holocaust, I unpack the interests of each creator, noting especially the maker’s proximity to the events (e.g., as survivor, resident of America during the Holocaust, child of a survivor). Tracing the vicissitudes of the Warsaw Ghetto’s deployment in culture, my goal is to offer an index to the concerns of American Jews and their attitudes about the Holocaust. To that end I pursue the following questions: What is the creative imprint of the ghetto and its catastrophic history? How are artistic representations of the ghetto linked to shifting conceptions of Jewish American identity and life in the Diaspora? How does art enter social and political consciousness? How is art politicized, or even depoliticized, and interpreted by a diverse viewing public? Why has this seminal moment and place in European history, thousands of miles away, been claimed by Americans, and so persistently, for more than half a century? Throughout, I consider how creation and interpretation are affected when memory, politics, and aesthetic concerns intertwine in the making of art. Thus, my project sheds new light on the importance of the Warsaw Ghetto as a site of memory, trauma, and creative struggle and illuminates its under-appreciated role as a litmus test of postwar Jewish American identity. For readers who do not know about the Warsaw Ghetto and the insurrection that took place there, this book will not only apprise them of it but will place it for them in time and in art.

To set the stage for what is to come, I begin with a historical profile of the Warsaw Ghetto and initial details about the uprising. At the outbreak of World War II, Jews made up around one-tenth of Poland’s population and one-third of Warsaw’s, the largest Jewish community in Europe. Numbering approximately 400,000, Jews lived, worked, and contributed to the thriving city. Before the ghetto’s assault on Jewish dignity, Warsaw was a tranquil place where Jews could mark their days by their worldly engagements as much as by age-old tradition. With the onset of war, initiated by the Nazi blitzkrieg invasion and Poland’s rapid fall and surrender in late September 1939, Jews were immediately persecuted. The Germans slowly introduced a growing number of unnerving restrictions: Jewish bank accounts were frozen, businesses publicly marked, and identifying armbands mandated. On November 15, 1940, Warsaw’s Jews were quarantined in a ghetto three and a half miles square, comprising only 2 percent of the city’s space, with all entrances sealed the next day. Soon they were more strongly isolated behind red brick walls more than ten feet high and reinforced with barbed wire. Living in a mere one hundred square blocks and in only 27,000 tiny apartments, Jews were confined in startling numbers: 240,000 in September, 360,000 by November, and over 470,000 by the summer of 1941. Everyday life in the overcrowded ghetto consisted of begging and destitution. Dead bodies lay in the teeming streets, along with starvation and widespread disease, not to mention fear of an unprovoked attack or deportation.

Any Jew caught outside the congested ghetto without a pass was subject to death. Trapped within their walled prison, Jews suffered from insufficient clothing and nourishment; in 1940 the daily food ration was 413 calories and the following year only 253. Deteriorating conditions and inadequate sanitation led to rampant disease, especially typhus. The Judenrat (Jewish council), headed by Adam Czerniakow, ruled the ghetto and was compelled to impose Nazi decrees on their coreligionists, including the excruciating order that they choose who would be deported to death camps. By spring 1942, liquidation had begun as the Final Solution gained currency; from July to September 1942, 265,000 Jews were deported to Treblinka, where most suffered a brutal, genocidal death, and thousands of others were sent to slave-labor camps. In January 1943, only 60,000 Jews remained in the ghetto when a second series of mass deportations began. Realizing that the noose had tightened and they had little left to lose, a number of Jews mounted a small resistance, allowing some deportees to escape. Heartened by this success, even as one thousand Jews died fighting and desperation swept through the ghetto, the rebels united factions and organized the larger revolt, now known as the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

When German troops entered the ghetto for the final liquidation on April 19, approximately 50,000 remaining residents were in hiding. With scant weapons, many homemade, the Jewish insurgents surprised the Germans, who retreated after a dozen men were wounded or killed. To force out the Jews, the SS set fire to the ghetto on the third day of fighting. Stubbornly clinging to a desire to die with honor, about 750 partisans staved off the Nazi juggernaut until May 16. Twenty-three-year-old uprising commander Mordecai Anielewicz perished in a bunker at Mila 18, either after a German gas attack or by his own hand. A few survivors managed to escape to the “Aryan” side through sewers, including deputy commander Antek Zuckerman, but most either died in the ghetto or soon after their transport to Treblinka. As a capstone to the Germans’ hard-earned victory, General Jürgen Stroop ordered his troops to destroy the Great Synagogue, on Tłomackie Street, with the commander managing the detonator himself. The uprising, a final effort to save the heart of eastern European Jewry, has since come to stand as the Holocaust’s archetypal act of resistance, not only in the United States but also throughout the world.

While versions of the Warsaw Ghetto have been constructed in America differently at different times, it is not quite so in Israel, which privileges the uprising and airbrushes the ghetto experience. Evidence of the uprising’s importance to the self-conception of post-Holocaust Israeli Jewry is manifest in the date and name proposed to commemorate the largest genocide in history: April 19, the start of the ghetto’s rebellion. Israelis rejected that date for several reasons, not least of which is its proximity to Passover. Originators in Israel felt that Passover, a joyous holiday that celebrates Jewish emancipation, and Yom Hashoah (Hashoah means “the catastrophe” or “utter destruction”), a solemn day that memorializes the destruction of European Jewry, should remain separate. Held annually on the twenty-seventh day of Nissan (April or May), Yom Hashoah shifts in the American calendar because of the lunar nature of the Hebrew year. Although the event was separated from the date of the uprising, the opening ceremony in Israel takes place in Warsaw Ghetto Square, located at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum and official site of commemoration. The day’s full name, Yom HaZikaron laShoah Ve-laG’vurah, translates as “Day of Remembrance of the Holocaust and the Heroism,” thereby recollecting devastation and valor equally, even though the latter pales in comparison to the former. Yad Vashem’s full name also links death and the Jewish fight for life: The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority. What I am getting at is that there are some points of connection between American and Israeli interests in the ghetto, notably the heroics of the fight. American responses, though, are driven by diverse goals and ideals, whereas the Israeli response to the uprising has been mostly homogeneous—stressing the uprising to the exclusion of ghetto life. More fixed, local concerns guide Israelis. From the start—and especially during the founding years with Israel under siege—Zionist ideology depended on the negation of the so-called weak, diasporic, old Jew and the exaltation of the sabra: the bold, pioneering, new Jew. The Warsaw Ghetto uprising suitably supported that cause. In contrast, the United Nations has no connection with, or need for, the uprising and thus in 2005 established January 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day, a date coinciding with the Soviets’ liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

First lauded by Jews in multiple publications, the uprising eventually became mythologized by, and for, a broader American audience. Take the American Jewish Yearbook’s coverage just months after it occurred, which in four short paragraphs self-consciously used the word “heroic” twice. With little information yet known, the author reports on the “heroic leaders of the ghetto uprising” and characterizes the battle as “a daring, if futile thing for the Jews to undertake against the overwhelming superiority of the enemy. But even from the garbled and clouded reports received so far, we can piece together a heroic story that will forever light up the dark and sordid tale of the Nazi-built Warsaw ghetto. . . . If, after achieving their ‘victory,’ the Nazis proceeded to liquidate the ghetto, it must have caused ironical laughter somewhere—but it was not the Nazis who laughed.” Soon thereafter an article in the Evening Star, then the premier newspaper in Washington D.C., printed an article histrionically titled “Homage to the Christian Poles and the Maccabean Jews of Warsaw!” The title itself exalts Jewish heroism by invoking fighting Jews of yore, complemented by the author’s melodramatic prose: “In the heart of Warsaw the most unmartial of peoples, the most helpless and lost, had turned their prison into a fortress and were prepared to the last child to make their tormentors pay dearly for every life. The wailing walls had become stockades. . . . The battle represents one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of religious and racial strife . . . the Jews, by their battle, sent out a call to all men: endure no longer! fight!” The Jewish periodical Menorah Journal, heartened by this outside report, reprinted the article before the table of contents of the summer issue.

Whereas the New York Times dispassionately accounted for the insurrection as it occurred, the paper a year later printed an editorial lauding the fight with awe and respect: “It is not only Jews who, this week, observe the first anniversary of the Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto. All faiths and creeds thrill at the heroic story. All the free world stands uncovered in profound respect for those brave men, women and children who, almost barehanded, fought the tanks and the guns of the Nazi beast through thirty-five days of horror and died rather than yield. . . . Warsaw will be a beacon for humanity for centuries to come.” Chapter 1 looks at related early cultural manifestations of the uprising, wherein the valor and self-determination of the partisans were eagerly eulogized to several ends. As depicted in radio plays, stage plays, and even fine art, the revolt was used as a vehicle to spur America to further action, its portrayers hoping to bolster support for trapped Jews in Europe by demonstrating that Jews took “heroic” responsibility for themselves and were not impotent, helpless sheep led to slaughter. A compelling tool of propaganda, the ghetto also offered an opportunity to demonstrate—to prove—Jewish suffering and therefore Nazi crimes.

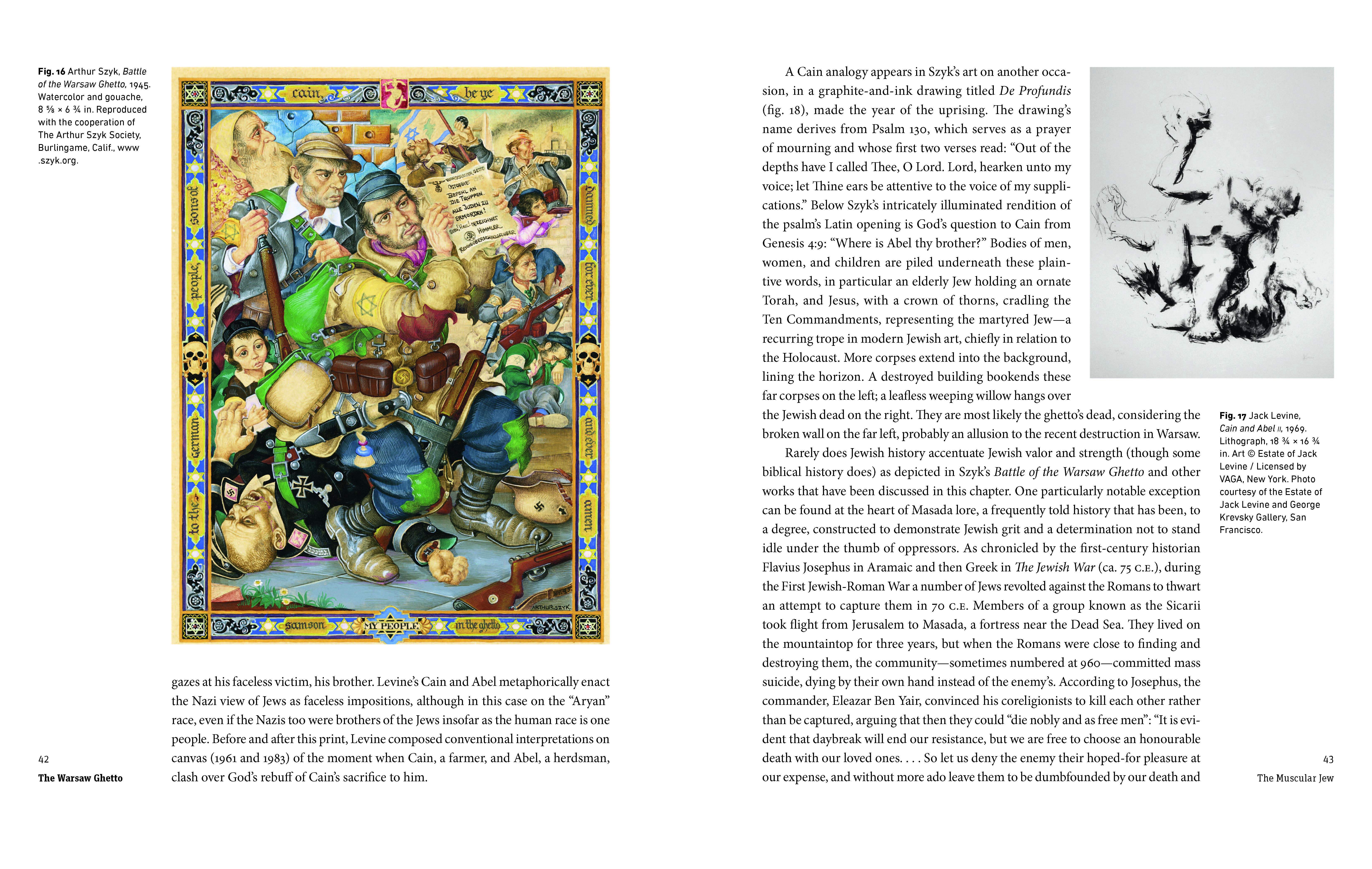

Unsurprisingly, American cultural producers have over the years paid close attention to the ghetto’s idealized muscular Jews, but the ghetto has served as much more than a platform to instill pride and extol courage in the face of overwhelming victimization. As an opportunity to call attention to the Jewish experience outside the concentration camps, the Warsaw Ghetto provided artists with malleable material for their work. While artist Arthur Szyk, author Leon Uris, and others made the resistance and the heroic fighting Jew their primary focus—the subjects of chapters 1 and 3—survivor Samuel Bak, in a series of paintings based on the iconic photograph from the Stroop Report of a little boy in the Warsaw Ghetto with his hands held up (whom for ease of reference I call throughout this book the Warsaw Ghetto boy, as he is commonly named elsewhere), does not address the uprising at all. As described in chapter 4, Bak’s paintings speak to issues of innocence, memorialization, and mercilessness and likewise stand as creative expositions of the permanent breach in his life—one of a number of examples that reveal how children fit into the ghetto’s story. Chapter 5 continues this theme by examining how the Warsaw Ghetto figures into comics, chiefly those that feature the survival of children to demonstrate, however feebly, that a vestige of hope survives even if few Jews do. The writers discussed in chapter 2—Rod Serling, Millard Lampell, and John Hersey—set their sights on family relationships, with the uprising as mostly a footnote in their conceptions. None of this trio was interested in tidy narratives; they crafted layers and contradictions for which the general American public, accustomed to Anne Frank’s naïve idealism and simplified characterizations, was somewhat unprepared.

Films like Roman Polanski’s Academy Award–winning historical drama The Pianist make especially evident the severe deprivation in the insular ghetto, but the disease-ridden ghetto finds prominence in almost all of the projects herein. Some representations aim explicitly to shock and overwhelm in their barbarity, like Charles Reznikoff ’s sweeping poem Holocaust and Joe Kubert’s graphic novel Yossel: April 19, 1943, both unrelenting in detail and devoid of any catharsis. As further considered in chapter 5, expressly in an extended discussion of Yossel, some artists exploit the emotional power of the Holocaust by depicting children. Whether confronted with children’s suffering and death or with their unlikely survival—and thus the fleeting glimmer of hope that survival stirs—readers and viewers are reminded of all that was lost. My claim, which I hope this study demonstrates, is that the Warsaw Ghetto cannot be simplified as only the example of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust, and that many other stories inhere in the history of the largest ghetto under Nazi dominion.

(Excerpt ends here)

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.