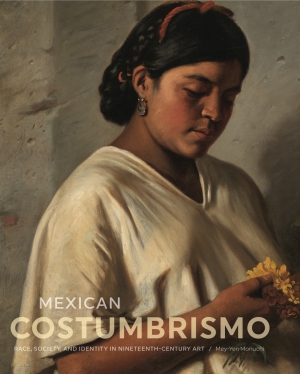

Mexican Costumbrismo

Race, Society, and Identity in Nineteenth-Century Art

Mey-Yen Moriuchi

“This meticulous study of images of everyday social customs in nineteenth-century painting, literature, and photography in Mexico makes an outstanding contribution to the field of art history. Moriuchi’s analysis enriches our understanding of the relation between the aesthetic and the political during Mexico’s tumultuous and pivotal period of nation formation. Her conclusions have important implications as well for the art-historical study of the preceding colonial era and of twentieth-century Mexican modernism.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

In contrast to the neoclassical work favored by the Mexican academy, costumbrista artists portrayed the quotidian lives of the lower to middle classes, their clothes, food, dwellings, and occupations. Based on observations of similitude and difference, costumbrista imagery constructed stereotypes of behavioral and biological traits associated with distinct racial and social classes. In doing so, Mey-Yen Moriuchi argues, these works engaged with notions of universality and difference, contributed to the documentation and reification of social and racial types, and transformed the way Mexicans saw themselves, as well as how other nations saw them, during a time of rapid change for all aspects of national identity.

Carefully researched and featuring more than thirty full-color exemplary reproductions of period work, Moriuchi’s study is a provocative art-historical examination of costumbrismo’s lasting impact on Mexican identity and history.

E-book editions have been made possible through support of the Art History Publication Initiative (AHPI), a collaborative grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

“This meticulous study of images of everyday social customs in nineteenth-century painting, literature, and photography in Mexico makes an outstanding contribution to the field of art history. Moriuchi’s analysis enriches our understanding of the relation between the aesthetic and the political during Mexico’s tumultuous and pivotal period of nation formation. Her conclusions have important implications as well for the art-historical study of the preceding colonial era and of twentieth-century Mexican modernism.”

“Rooted in casta imagery of eighteenth-century New Spain as well as the works of nineteenth-century foreign traveler-artists in Mexico, Moriuchi’s study demonstrates that such visualizations of racial and social diversity informed the twentieth-century concept of mexicanidad in the art produced by Mexican modernists. For students and scholars, this book significantly advances the scholarship on the visual cultures of Mexico.”

“Mexican Costumbrismo represents a considerable step forward in the bibliography on Mexican (and, by extension, Latin American) art of the nineteenth century. Moriuchi’s firm grasp of the art, social, and literary history of Mexico in the transitional era from colony to republic serves to create a nuanced, richly documented, and stimulating panorama of daily life and its imagery in a variety of visual genres. Moriuchi intelligently argues that seemingly straightforward scenes of ‘picturesque' customs are often allusions to far more complicated sets of social circumstances.”

“This thoughtful, fine-tuned study peels apart the layers of costumbrista painting, literature, and photography to reveal their centrality to discourses of nationhood and national identity in Mexico in its unstable first century of independence. Keenly sensitive to the ways in which race, class, and gender were both represented and misrepresented by costumbrismo’s artists and consumers, Moriuchi’s book demonstrates the complexity and relevance of a genre that well merits fresh attention.”

“Mey-Yen Moriuchi’s book is a noteworthy contribution that expands our understanding of a significant genre of art production in nineteenth-century Mexico and wider Latin America. Its comprehensive approach makes it a valuable resource for specialists as well as for scholars and students unfamiliar with nineteenth-century Mexican art.”

Mey-Yen Moriuchi is Assistant Professor of Art History at LaSalle University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

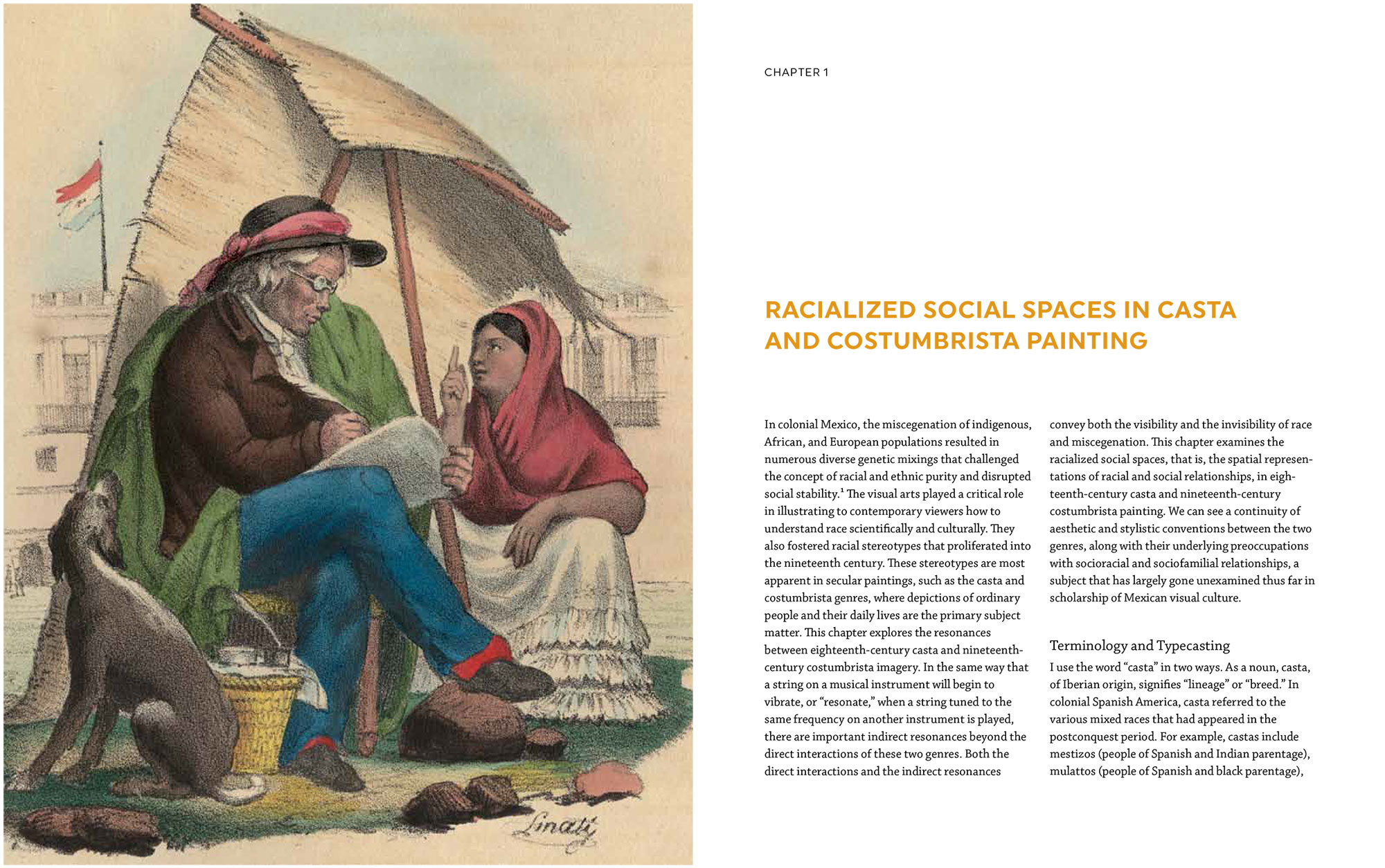

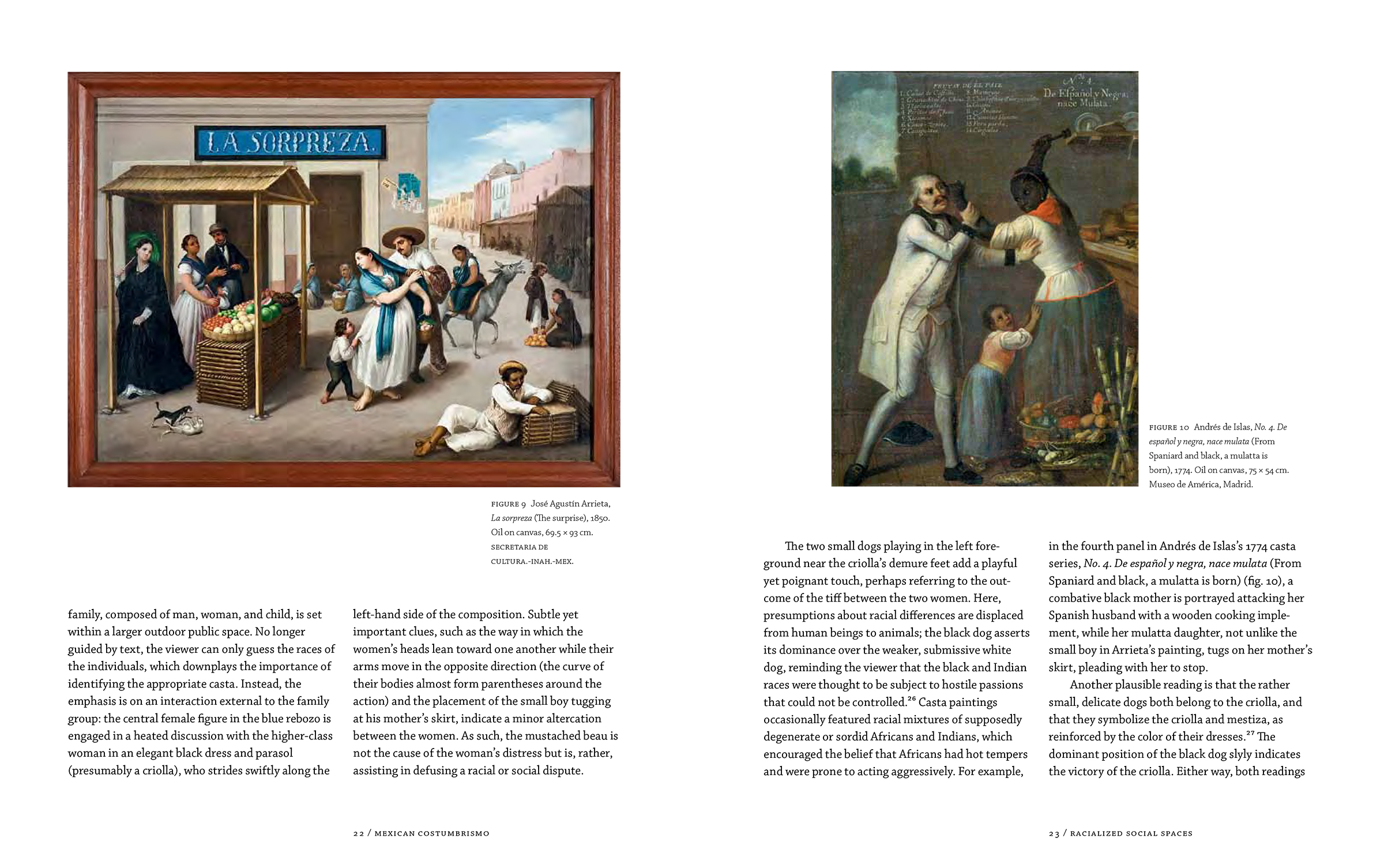

1. Racialized Social Spaces in Casta and Costumbrista Painting

2. Traveler-Artists’ Visions of Mexico

3. Literary Costumbrismo: Celebration and Satire of los tipos populares

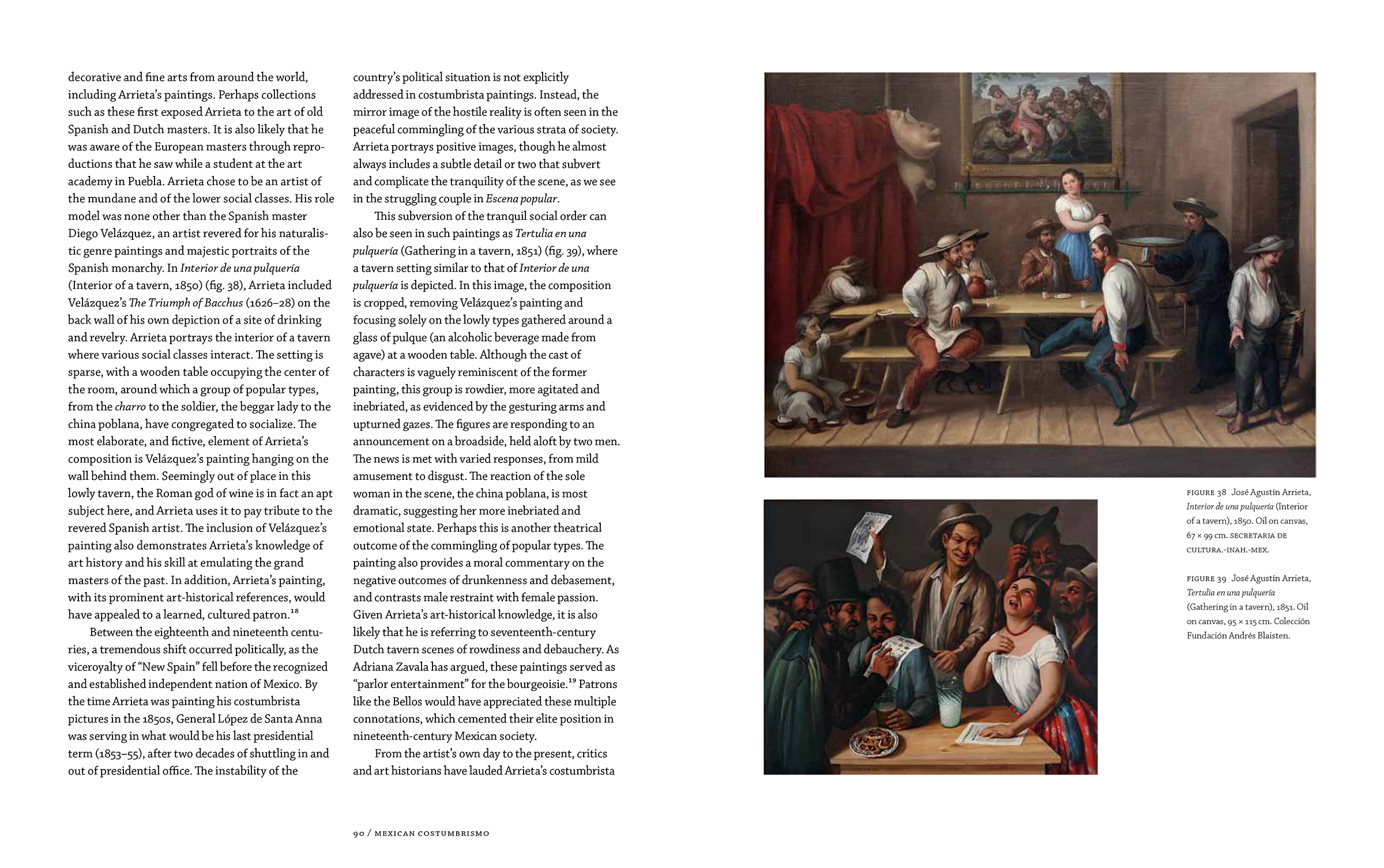

4. Local Perspectives: Mexican Costumbrista Artists

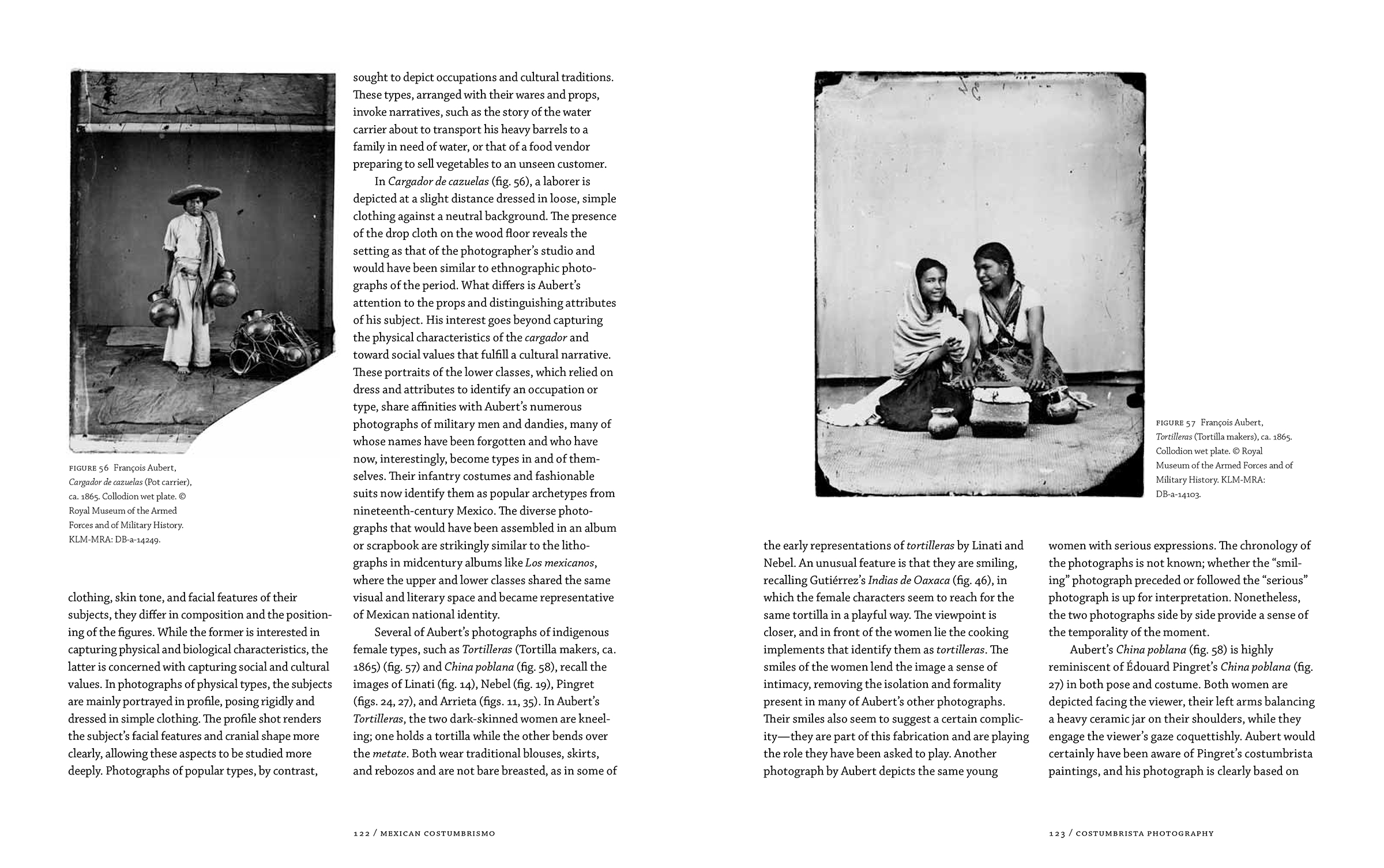

5. Costumbrista Photography

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

From the Introduction

In 1854, a group of Mexican writers published an illustrated collection of essays titled Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos (Mexicans painted by themselves) that described a variety of stock figures meant to represent Mexico’s diverse populace. Inspired by European books about popular social types and trades, such as Heads of the People, or Portraits of the English (1840–41), Les français peints par eux-mêmes (1840–42), and Los españoles pintados por sí mismos (1843–44), the Mexican collection contributed to a transnational debate in the nineteenth century about what constituted a nation and who represented it. In the frontispiece of the Mexican album (fig. 1), various social and racial types gather in front of a large white sheet upon which the title of the book is printed in block letters. The sheet forms an informal screen and alludes to a magic lantern show, an early type of image projection that displayed painted pictures or photographs. The magic lantern screen, and the man who points toward the assembled characters, suggest that in the following pages we will find representations of the types being advertised in the frontispiece. These renderings will reveal a sense of who and what make up the nation that is imagined to be Mexico.

The years following independence in 1821 were critical to the development of social, racial, and national identities in Mexico. The visual arts played a decisive role in this process of self-definition. This book seeks to reorient our understanding of this crucial yet often overlooked period in the history of Mexican art by focusing on a distinctive genre of painting and literature that emerged between approximately 1821 and 1890 called costumbrismo, of which Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos is an example. Costumbrismo designates a cultural trend in Latin America and Spain toward representing local customs, types, costumes, and scenes of everyday life, and it offers a powerful statement about shifting terms of Mexican identity that had a lasting impact on Mexican history. Costumbrismo emerged in the nineteenth century as the nation’s leaders tried to stabilize the country both politically and economically. Mexico struggled to create an independent nation in the wake of Spanish colonialism, a period of approximately three hundred years; American intervention (1846–48), when the United States acquired Mexican land that now makes up the southwestern and western United States; and the French occupation under Emperor Maximilian (1862–67). Many nations formulated their national identities during the nineteenth century, but in Mexico the need for new imagery may have been truly urgent, as these political aggressions by foreign powers increased the desire for independence on the part of criollos, as people of Spanish descent born in the Americas were known.

Following independence from Spain, approximately forty different political leaders ruled Mexico. The first empire, under the self-proclaimed emperor Augustín de Iturbide, lasted only eighteen months. A series of revolts and wars and their accompanying political turmoil characterized the rest of the nineteenth century. Over a nine-year period, from 1824 to 1833, there were seven presidents. Only one, Guadalupe Victoria, served a complete four-year term. One of the most famous leaders of this era was General Antonio López de Santa Anna, who towered over Mexican politics for nearly forty years and shuttled in and out of the presidency from 1833 to 1855. Benito Juárez led La Reforma (the reform era), bringing free-market capitalism, private property rights, and an end to the prominent role of the Roman Catholic Church in economic affairs. His liberal policies provoked the aforementioned French intervention in 1862 and Emperor Maximilian’s ascension in 1864. Juárez and the Liberal Party’s return to power during the Restoration (1867–76) ultimately could not secure stability for the nation. Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship rounded out the end of the century. His reign over Mexico from 1877 to 1910, known as the Porfiriato, was characterized by its pursuit of “order and progress” and positivist policies.

While this political turmoil plagued the nation, costumbrista artists captured the ordinary and mundane in their representations of daily Mexican life. Political strife was generally not the focus of their everyday scenes, yet undercurrents of social negotiation and identity construction permeate their compositions. Costumbrismo’s quotidian subject matter has contributed heavily to its relative obscurity in Mexican art history and subsequent scholarship. It has largely been dismissed as picturesque and inconsequential. The nineteenth-century Mexican academy favored neoclassical ideals and conservative artistic training. According to tradition, costumbrista and genre painting were surpassed in prestige by the more intellectually stimulating genres of history painting, portraiture, and even landscape. Like seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish genre artists or nineteenth-century French realist painters, costumbrista artists sought to portray the everyday lives of the lower and middle classes: their clothes, food, dwellings, and occupations. Costumbrista artists endeavored to represent what they saw rather than cater to traditional academic standards. I argue that their work contributed to the documentation and reification of social and racial types—reinforcing and reimagining cultural norms by pictorializing the costumes and comportment of everyday individuals in their surroundings.

It should be noted that Mexican identity in this context was an elite construct dominated by men. It was an ideal in the service of maintaining an existing social and racial hierarchy, which in turn created a false sense of unity. This notion of Mexican identity suggested that “all citizens,” despite differences in class, gender, and race, supported the national project and the status quo. This positioning of identity situates itself “within, not outside representation,” as Stuart Hall observes. In constructions of cultural identity, Hall notes, ties to the historical past, language, and culture are in the process of becoming, not being. It is not so much a question of “who we are” or “where we came from,” but rather “what we might become, how we have been represented and how that bears on how we might represent ourselves.” These identities, though rooted in tradition and “reality,” arise in the imaginary and are also partly constructed in fantasy.

Costumbrista images are based on observations of similitude, essentially constructing stereotypes of behavioral and biological traits associated with various racial and social classes. However, this classification of similarities is consciously dependent on concurrent claims of difference and isolation. The apparent paradox of similarities that depend on difference, and how this paradox affects nineteenth-century notions of representation and identity formation, are at the heart of this book. As human beings attempt to understand the vast world we inhabit, we organize objects, people, and concepts on the basis of affinities and differences. In theories of difference, difference is explained in relation to its opposite, sameness. Identity and sameness can be both synonyms and antonyms of difference. As Mark Currie points out, “the dictionary defines identity as both ‘absolute sameness’ and ‘individuality’ or ‘personality.’ The slippage here derives from an ambiguity about the points of comparison and antithesis that are in operation. ‘Identity’ can clearly mean the property of absolute sameness between separate entities, but it can also mean the unique characteristics determining the personality and difference of a single entity.” Or, as Hall argues, “identity is always, in that sense, a structured representation which only achieves its positive through the narrow eye of the negative. It has to go through the eye of the needle of the other before it can construct itself.” Identity construction is in constant negotiation with the Other, and revolves around the process of “othering.” It entails a self-reflection of the individual with respect to a greater, differentiated society. In my examination of costumbrismo, I investigate this dialectic between individual particularism and what can be generalized about an “otherized” community.

I also examine the dialectic between universality and difference. In the nineteenth century, political leaders and the cultural elite in the West assumed that what was universal was European. This perceived universalism operated as a technology of empire through its assumption of the characteristics of those in politically dominant positions. As part of the language of identity construction, costumbrista imagery engaged this dialectic of universality and difference, transforming the ways in which Mexicans saw themselves and how other nations saw them.

Costumbrismo, as a cultural and artistic movement, played a significant role in the construction of racial and social types and was thus integral to the formation of modern notions of Mexican identity.

I consider costumbrismo as a product of the “coloniality of power.” Aníbal Quijano coined this term to describe the legacies of European colonialism in postindependence Latin American societies. Racial, political, and social hierarchies that had been imposed during European rule survived in the form of social and racial discrimination that is embedded in contemporary social orders. Quijano argues that the sistema de castas (caste system) imposed during the colonial era, which was based on phenotypes and skin colors and which privileged the Spaniards over indigenous races, endures in postcolonial societies. Costumbrismo’s creation and popularity was formulated within a persistent categorical and discriminatory discourse. In this book, I investigate the images of traveler-artists who portrayed Mexican types from a foreign perspective, and I consider these as integral to the formation of a national Mexican identity. These works of the 1840s and ’50s were important models for the writings and images created by Mexican artists during the costumbrista movement. Mexican writers and artists sought to reclaim as their own the social and racial types that had captured the curiosity of traveler-artists. In representing their daily surroundings and the popular inhabitants of these everyday spaces, local artists and writers wanted to claim what was national and Mexican. These artists and writers were, however, from the privileged classes, and they provided the dominant perspectives of outsiders looking in, despite their attempt to disrupt a hegemonic center-periphery model.

Terms and Terminology

A few words need to be said regarding terms, in particular with respect to the words “costumbrismo,” “type,” and “typecasting.” Costumbrismo was essentially an instance of typecasting—a means of creating stock characters or archetypal figures (types) that could be used and reused to represent certain personality traits, behaviors, races, occupations, and social statuses. Figures could be distinguished by their dress, facial expressions, bodily gestures, accessories, and settings. As a result, acute attention to detail and an exacting realist style characterize much of the genre.

Los tipos populares and les types populaires describe the results of this typecasting phenomenon in Spain and France, respectively. “Popular types,” the term’s direct translation into English, does not have the same ring, common usage, or connotations as its Spanish and French equivalents. Nevertheless, it is the most direct translation, and I use the term “popular types” to refer to the characters that became popularized and nationalized in the public’s eye.

The term “costumbrismo” was not used until 1895, in an article by the Spanish novelist and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno. The term “costumbrista” appeared for the first time in 1915 in the Diccionario de la lengua española by José Alemany y Bolufer, in reference to those who wrote about costumbres (customs), not to an actual type of text or image. In the nineteenth century, essays and images of everyday life were described as cuadros de costumbres (pictures of customs) or bosquejos de costumbres (sketches of customs). Costumbrismo became very popular in the nineteenth century, sharing affinities with both romanticism and realism, though antecedents of the genre can be found in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Though costumbrismo referred to the literary or pictorial interpretation of everyday life, culture, and mannerisms in Spain and Latin America, this tendency toward social observation was prevalent throughout Europe and originated in England and France. Walter Benjamin, in The Arcades Project, coined the term “panoramic literature” to describe the essays, periodical literature, and books dedicated to observing and dissecting society. The nineteenth century saw a surge in the desire to capture one’s quotidian surroundings and to use such observations to make generalizations about behavior, identity, and nation. The use of social types to represent a nation’s identity was a transnational endeavor.

(Excerpt ends here)

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.