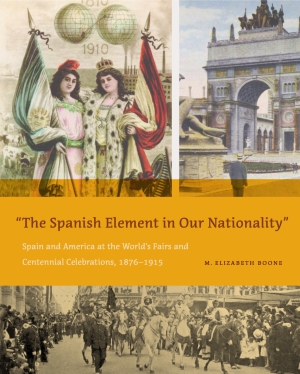

“The Spanish Element in Our Nationality”

Spain and America at the World’s Fairs and Centennial Celebrations, 1876–1915

M. Elizabeth Boone

“The Spanish Element in Our Nationality”

Spain and America at the World’s Fairs and Centennial Celebrations, 1876–1915

M. Elizabeth Boone

“Special attention is devoted to Spanish art in the 19th century—presented through remarkable plates and photographs—including paintings, architectural displays, and rare materials.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Written histories invariably record the Spanish financing of Columbus’s historic voyage of 1492, but few consider Spain’s continuing influence on the development of U.S. national identity. In this book, M. Elizabeth Boone investigates the reasons for this problematic memory gap by chronicling a series of Spanish displays at international fairs. Studying the exhibition of paintings, the construction of ephemeral architectural space, and other manifestations of visual culture, Boone examines how Spain sought to position itself as a contributor to U.S. national identity, and how the United States—in comparison to other nations in North and South America—subverted and ignored Spain’s messages, making it possible to marginalize and ultimately obscure Spain’s relevance to the history of the United States.

Bringing attention to the rich and understudied history of Spanish artistic production in the United States, “The Spanish Element in Our Nationality” recovers the “Spanishness” of U.S. national identity and explores the means by which Americans from Santiago to San Diego used exhibitions of Spanish art and history to mold their own modern self-image.

“Special attention is devoted to Spanish art in the 19th century—presented through remarkable plates and photographs—including paintings, architectural displays, and rare materials.”

“With ‘The Spanish Element in Our Nationality,’ M. Elizabeth Boone confirms her role as the leading interpreter of the complex interactions between the United States and Spain as revealed in the visual arts. This thoroughly researched analysis of key international expositions held between 1876 and 1915 demonstrates the nuances of these trans-Atlantic relations and provides insight into Hispanic/Latinx identity and presence in the United States over a century later.”

“Pioneering in every respect, this handsomely-illustrated volume offers unique insights into the extent to which political circumstances, combined with long-standing racial and religious prejudices, frustrated Spain’s campaign for recognition of the artistic and creative genius of its people at various world’s fairs. The volume is a must for anyone interested in Spain’s modern history along with those concerned with attitudes towards the place of both Spanish and Hispanic culture in the United States.”

“A meticulously researched and engagingly written account of the genesis, the promotion, and also the avoidance of Spanish identity and culture, including in Spain’s former colonies. This impressive book is a major contribution to transnational cultural studies, demonstrating Boone’s deep and nuanced command of Spanish, Latin American, and U.S. art and culture.”

“The Spanish Element in Our Nationality mines a wealth of visual and textual evidence from the later 19th and early 20th century world’s fairs in order to convincingly demonstrate Spain’s marginalization in the construction of an American identity that leaned more heavily toward England. While well-versed in theoretical approaches to its subject and detailed in unraveling the complexities of Spain’s reception at world’s fairs, Boone’s book remains grounded in a careful examination of the fine arts and material culture, and how the visual arts functioned politically in an international context.”

“A wonderfully detailed investigation of the shaping of Spain’s national-ethnic identity through several key international exhibitions with art in the United States and Latin America. Drawing upon unpublished archival sources, the engaging study analyzes the strategies of, and the international stakes for administrators, statespersons, and critics from different nations. This book offers readers an indispensable understanding of the politics of display in the creation and reception of these exhibitions.”

“This book is groundbreaking and an important tool in helping us all get a richer, more complete, and much more realistic view of the Spanish past and contributions to making the United States what it was to become.”

“This book offers the interested reader an excellent gateway to think visual cultures in dialogue with the objective of the nations at the time of the composition of collections that synthesized national imageries and, at the same time, to discover which elements were included and excluded in the consolidation of those canons. From my perspective, it is, in turn, a contribution to think the construction of national patrimony in a way that is more dynamic and attentive to quite different elements and actors.”

“The Spanish Element in Our Nationality is a welcome contribution during an important historical moment, when the US relationship to its Hispanic heritage and present-day culture is being reconfigured. July 29, 2020, marked the establishment of the National Museum of the American Latino with the approval of the US Congress, as part of the omnibus spending bill. Drawing on the visual culture of the nineteenth-century World’s Fairs, Boone’s book puts in perspective the historical origins of the tension between the US and its Spanish roots.”

“‘The Spanish Element in Our Nationality’ is a must-read revisionist project of great urgency for Americanists, Latin Americanists, and Iberianists who wish to better understand the interconnectedness of their cultural histories and to shape more inclusive scholarship.”

“[The Spanish Element in Our Nationality] is an informative work and a mustread for individuals interested in art history, world’s fairs, immigration to the United States, and US-Spanish-Latin American relations at the turn of the twentieth century.”

“[“The Spanish Element in Our Nationality”] illuminates American ideological objectives in the representation of national pasts through international and commemorative fairs and, perhaps more importantly, invites us to be alert to other ways and moments in which the United States shares a history and aesthetics with Spanish and Latinx cultures.”

M. Elizabeth Boone is Professor of the History of Art, Design and Visual Culture at the University of Alberta. She is the author of Vistas de España: American Views of Art and Life in Spain, 1860–1914.

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Inventing America at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial

2 Defining (and Defending) Spain in Barcelona and Paris, 1888 and 1889

3 Marginalizing Spain (and Embracing Cuba) at the 1893 Columbian Exposition

4 Reasserting Spain in America at the 1910 Centennial Exhibitions

5 Using Spain to Ignore Mexicans at the 1915 California Fairs

Notes

Bibliography

Index

From the Introduction

Walt Whitman was right. “We Americans,” wrote the poet and essayist in his 1883 essay “The Spanish Element in Our Nationality,” “have yet to really learn our own antecedents, and sort them, to unify them. They will be found ampler than has been supposed, and in widely different sources. Thus far, impress’d by New England writers and schoolmasters, we tacitly abandon ourselves to the notion that our United States have been fashion’d from the British Islands only, and essentially form a second England only—which is a very great mistake.” “To that composite American identity of the future, Spanish character will supply some of the most needed parts,” continued Whitman, in recognition of Spain’s relevance to United States. He was writing in honor of the 333rd anniversary of Spanish settlement in Santa Fe, in the U.S. Territory of New Mexico, but scholars, among them historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto, are only now beginning to “show that there are other US histories than the standard Anglo narrative.” This book aspires to a similar goal. The thirteen colonies that banded together to form the United States of America in 1776 had indeed been colonial possessions of the English, but to define a nation that now encompasses much more than a singular strip of Atlantic coastline in such narrow and universalizing terms ignores the contributions of the many others who also participated in the founding moments and complex histories of the nation. This book seeks to understand one such underrecognized history of the United States—the Spanish—in order to facilitate the embrace of a diverse, more just, and multinational future.

How an English-only definition of U.S. national identity developed is jokingly explained by D. S. Cohen and H. B. Sommer in their irreverent history of the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, titled Our Show: A Humorous Account of the International Exposition. “If the late Christopher Columbus, Esq., could have foreseen, as an indirect result of his little excursion in the spring of 1492, the infliction of the following pages upon posterity, Mr. Columbus, very likely, would have stayed at home.” Spain, the country that financed Columbus’s historic voyage across the Atlantic, came to exactly the same conclusion, staying home from the San Francisco World’s Fair some forty years later, in 1915. In 1876, the Spanish government installed an impressive display of agricultural and industrial products, financed the construction of three buildings, and shipped a valuable collection of paintings from the national museum to Philadelphia for exhibition on the grounds of Fairmount Park. Seventeen years later, in 1893, the Spanish sent to Chicago’s Columbian Exposition another large display of fine art, designed two richly ornamented architectural spaces for the exhibition of manufactured and agricultural goods, and collaborated with the United States on the construction of three full-sized replicas of Columbus’s ships, the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. But in 1915, despite repeated invitations, a highly publicized fact-finding visit to San Francisco by the Spanish commissioner of tourism and culture, and a direct appeal to the Spanish king, the Spanish decided not to participate in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The Spanish were likewise absent from the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, organized that same year as a fantasy Spanish city sited in a part of the United States that for more than three centuries, until Mexico won independence in 1821, had been part of Spain’s extensive colonial empire. The question of why Spain stayed home from the California fairs is a complicated one, and the ways in which Spain and the United States subsequently constructed their histories, in comparison with and in contrast to each other, provide one important point of explanation.

Spain, between the years 1876 and 1915, was effectively written out of the history of the United States, which placed the origin of the nation at Plymouth Rock rather than in Florida, New Mexico, or any other part of the United States with Spanish roots that actually preceded the arrival of the English. Cohen and Sommer performed a similar sleight of hand, garbling facts and deliberately mistaking the fifteenth-century Catholic queen Isabella I for Queen Isabel de Borbón, who had been deposed in 1868. Columbus, they wrote, “was simply a Brazilian sea captain, who believed there were two sides to every question, even to such a serious question as the world. Having taught Queen Isabella of Spain, who had not then abdicated, how to make an egg stand and drink an egg-flip, she gave him, under the influence of the latter, command of the steamer ‘Mayflower,’ with permission to row out and see what he could find. He landed at Plymouth Rock [and] discovered the city of Boston.” The United States was English, and the importance of Spain, along with the multiple Spanish settlements founded in territory eventually incorporated into the United States, was largely rewritten, if not entirely forgotten. Ponce de León, who traveled with Columbus on his second journey across the Atlantic, journeyed north to Florida in 1513; Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón founded a settlement on the coast of Georgia in 1526; Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca began his journey across Texas and through the southwest in 1527; and Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded the city of St. Augustine, the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in today’s continental United States, in 1565, all well before the 1620 landing of the Mayflower. Regional histories celebrate these events, but the national history of the United States minimizes their importance and buries them from sight.

The fairs and exhibitions that mark the five historical moments examined in “The Spanish Element in Our Nationality” are used to trace this process of erasure and may be productively considered in parallel, contradictory, and intertwining ways. The primary structure of the book is provided by the exhibitions mounted in the United States—in Philadelphia in 1876, in Chicago in 1893, and in San Francisco and San Diego in 1915, the basis of chapters 1, 3, and 5. Catalan, French, and Latin American celebrations were mounted in the years in between—in Barcelona and Paris in 1888 and 1889 and in Buenos Aires, Mexico City, and Santiago de Chile in 1910—providing the basis for chapters 2 and 4. Four of the celebrations took place in the United States (Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, and San Diego); five received official recognition as world’s fairs (Philadelphia, Barcelona, Paris, Chicago, and San Francisco); and five commemorated violent revolutions that resulted in independence and the creation of new nations (Philadelphia, Paris, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, and Santiago de Chile). Each chapter uses the exhibition of paintings, the construction of ephemeral architectural space, and other manifestations of visual culture to build on issues of national display and nationhood toward a more comprehensive understanding of why the Spanish exhibitions were mounted and how they contributed, or were denied the opportunity to contribute, to the invention of national identity in the United States. The project draws on current literature in U.S., Latinx, Iberian, and Latin American studies and pays particular attention to theories of exhibition display, national identity and memory, and the interpellation of religion, politics, and economics by art and visual culture. In addition, it brings to scholarly attention a body of work that is largely unfamiliar to English-speaking scholars; while Spain’s seventeenth-century golden age has received ample attention, its nineteenth-century artistic production is largely unknown.

Cultural production in the United States and its relationship to Spain and the former Spanish colonies during the long nineteenth century has likewise only just begun to receive the attention it deserves.5 Early scholarship on the United States, produced in a mid-twentieth-century period of national confidence, was devoted to rediscovering the lives and work of individual artists and differentiating them from their English (and later French) contemporaries. John Singleton Copley became known primarily for his portraits of Boston colonials, Thomas Cole for his Hudson River School landscapes of the New Eden, and artists such as Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer for what was described as an intrinsically realist style and local subject matter. The next generation of scholars began to expand the canon of artists, adding women and artists of color to the list and questioning the assumption that art in the United States had developed in isolation from the world at large. Links were drawn to history, literature, and other fields in the arts, humanities, and social sciences, and new theoretical models were used to broaden the methods of engagement with art and visual culture. Connections to the cultural traditions of Germany and Italy were fruitfully examined, as were cultural interactions with North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Placing the art of the United States in an international context is high on today’s art-historical agenda, yet links to Spain still leave much to be explored.

Except for the paintings of Francisco Goya and Pablo Picasso, artistic production in Spain over the long nineteenth century has also been largely ignored in English-speaking America. I began offering a course on nineteenth-century Spanish art (playfully calling it “everything that happened between Goya and Picasso”) in the late 1990s, and this book introduces some of these forgotten artists, architects, and other cultural workers to a broader public. Comprehensive information about nineteenth-century Spanish art and visual culture is typically available only in Spanish texts with few reproductions, often of poor quality. Exhibition catalogues and trade publications, which generally feature better illustrations but receive poor distribution outside Spain, fill in some of the gaps by focusing on themes such as Spanish painters in Paris and Rome, views of particular cities, history and literary painting, gardens, and even night scenes. A complete catalogue of nineteenth-century Spanish painting at the Prado finally appeared in 2015, but books and exhibition catalogues based on national collections fail to include those artists and art forms not recognized by official history. Readers interested in the role of Spanish women will find few sources, all of them in Spanish. Those interested in institutional history can refer to books written in English by Oscar Vázquez and Alisa Luxenberg, and scholars concerned with periodical illustration may look to the work of Lou Charnon-Deutsch, but the recovery and wider dissemination of the history of nineteenth-century Spanish art, design, and visual culture, to say nothing of its relationship to the United States, is still very much a work in progress.

Placing the United States and Spain in dialogue facilitates another important goal for contemporary historians of art: understanding cultural production in the United States in the context of the Americas more broadly. The historical relationship between the United States and the rest of the hemisphere is characterized by competition, collaboration, and change, and the need for dialogue increased during the nineteenth century as the many nations of America (including the United States) negotiated their borders and developed their own distinct national identities. As these identities became more firmly defined, and as the United States became more powerful and potentially threatening, early nineteenth-century hopes for hemispheric unity were replaced by visions of difference. Pan-Americanism, closely linked to U.S. imperialism, developed simultaneously with Latin Americanism, which sought to unite Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking nations into a coalition in defense of its own interests and independent of the United States. The United States, in defining itself as an English-speaking Protestant nation, became the antithesis of Spanish-speaking and Catholic Latin America. Although most of the Latin American nations, with the exception of Brazil, were republics, and although many had similarly rich mineral and agricultural resources, difference from the United States, rather than similarity, became embedded in their distinct national identities.

The erasure of Spain from the United States has entrenched this impression of difference. Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, a Mexican-born historian who writes as fluently in English as in Spanish, saves his most trenchant observations about this issue for those who read him in his native tongue. While the official histories of Europe have been taken apart, examined, and reconstructed, claims Tenorio Trillo, historians of America have failed to move beyond the nineteenth-century model of the nation-state. In Historia y celebración: América y sus centenarios, he rhetorically questions the merit of this approach and warns of its future consequences: “Could not North American history become the symbol of a new relationship between Mexico, Central America, Canada, and the United States? Could it not become the symbol of a relationship in which recognition of cultural differences does not impede the assumption of a common past and present? Although some historians find it intellectually easy and academically profitable in the short term to defend the differences between Mexican and U.S. civilization, this route in the long run is both risky and unsustainable.” As historians of art and visual culture in the United States embrace an internationalist stance, a thorough interrogation of the processes by which current notions of the United States have failed to acknowledge this country’s shared history with Spain and the rest of Spanish-speaking America becomes ever more necessary. If the United States is America, in the everyday parlance of English, then the capacious nature of that word needs to be more fully recognized.

Excerpt ends here.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.