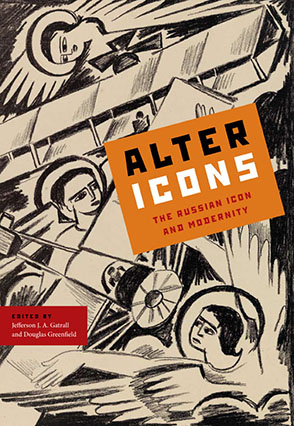

Alter Icons

The Russian Icon and Modernity

Edited by Jefferson J. A. Gatrall, and Douglas Greenfield

Alter Icons

The Russian Icon and Modernity

Edited by Jefferson J. A. Gatrall, and Douglas Greenfield

“This elegant volume, replete with full-color plates and multiple illustrations, demonstrates that far from falling into ‘decline,’ ‘decay,’ or ‘loss’ from its encounter with modern aesthetics, the Russian icon continues to serve its ‘intermedial,’ ‘liminal’ function, remaining a phenomenon of the paradoxical ‘living tradition’ that is Orthodoxy. By definition both material and spiritual, the icon finds a place in museum or poem as well as church, marketplace as well as film. And, as elucidated here, the obraz serves itself up as a subject for scholarly investigation as easily as an object of religious devotion. Kudos to the authors, editors, and publisher.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

In addition to the editors, the contributors are Robert Bird, Elena Boeck, Shirley A. Glade, John-Paul Himka, John Anthony McGuckin, Robert L. Nichols, Sarah Pratt, Wendy R. Salmond, and Vera Shevzov.

“This elegant volume, replete with full-color plates and multiple illustrations, demonstrates that far from falling into ‘decline,’ ‘decay,’ or ‘loss’ from its encounter with modern aesthetics, the Russian icon continues to serve its ‘intermedial,’ ‘liminal’ function, remaining a phenomenon of the paradoxical ‘living tradition’ that is Orthodoxy. By definition both material and spiritual, the icon finds a place in museum or poem as well as church, marketplace as well as film. And, as elucidated here, the obraz serves itself up as a subject for scholarly investigation as easily as an object of religious devotion. Kudos to the authors, editors, and publisher.”

“This groundbreaking book will be necessary reading for anyone invested in the icon—not only those concerned with its history in Russia but also those concerned with its widest ramifications in modernisms of the East and West. The essays examine from diverse viewpoints the largely unexplored centrality of the material icon in the imperialist Russian period as well as in the twentieth century. Not a passive object or simple mirror, the icon was an agent in these centuries that worked simultaneously for tradition and the avant-garde, for individual craftsmanship and mass production, for church devotion and museum ideologies, and more. These essays demonstrate not icons’ gradual disappearance and displacement, but rather the indispensability of the icon for any understanding of Russian culture, of its conflicting and complicated modernisms.”

“Well illustrated and designed, this book is a significant contribution to the study of Russian culture.”

“Icons can have profound political and social implications, and while the focus of the eleven chapters in this book is on the icon in modernity, there is enough material outlining the icon’s journey from medieval to the early modern to be of interest to any scholar of historical trends over the past millennium. . . . As many other reviewers have noted, this book is ground-breaking for its analysis of the traditional as well as innovative role of icons during a period where they were in danger of being eclipsed by the state apparatus. . . . After reading this work icons will never look the same.”

Jefferson J. A. Gatrall is Assistant Professor of Russian at Montclair State University.

Douglas Greenfield is Assistant Professor in the Intellectual Heritage Program at Temple University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Jefferson J. A. Gatrall

Part I: Empire of Icons

1. Strength in Numbers or Unity in Diversity? Compilations of Miracle-Working Virgin Icons

Elena Boeck

2. Between Purity and Pluralism: Icon and Anathema in Modern Russia, 1860–1917

Vera Shevzov

3. Nicholas II and the Russian Icon

Robert L. Nichols

Part II: Curators and Commissars

4. Anisimov and the Rediscovery of Old Russian Icons

Shirley A. Glade

5. Moments in the History of an Icon Collection: The National Museum in Lviv, 1905–2005

John-Paul Himka

6. How America Discovered Russian Icons: The Soviet Loan Exhibition of 1930–1932

Wendy R. Salmond

Part III: Intermedial Icon

7. Polenov, Merezhkovsky, Ainalov: Archeology of the Christ Image

Jefferson J. A. Gatrall

8. Avant-Garde Poets and Imagined Icons

Sarah Pratt

Part IV: Projections

9. Florensky and the Binocular Body

Douglas Greenfield

10. Florensky and Iconic Dreaming

John Anthony McGuckin

11. Tarkovsky and the Celluloid Icon

Robert Bird

Afterword

Vera Shevzov

Selected Bibliography

Contributors

Index

Introduction

Jefferson J. A. Gatrall

The Russian icon has led a storied existence since entering the modern world. The vicissitudes of passage have shaped even what it means to be an icon. Within the Orthodox community, of course, the icon did not cease to be a venerated image, as it had been in Russia since the eleventh century. Yet over the past two hundred years, the icon fell into new hands. Once under the care of their latter-day handlers, icons began to migrate en masse from churches and monasteries to museums, public exhibitions, and private collections. By the 1930s, the combined efforts of archeologists, art historians, restorers, curators, and collectors had succeeded in reconstituting the Russian icon as a globally recognized art form, one with distinct schools and its own history of styles. At the same time, the means of producing icons also changed hands. In the final decades of tsarist Russia, traditional icon painters, working in provincial centers, faced competition at both the high and low ends of their trade: while painters from the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts were winning a lion’s share of major new church commissions, Moscow factories were churning out household icons at reduced cost for mass consumption. Lastly, if the Russian icon has had its modern defenders, it has also endured modern waves of iconoclasm, notably in the wake of the 1917 Revolution and during World War II. Indeed, a number of medieval icons that were sold or smuggled abroad for safekeeping during the Soviet period are only now returning to Russian soil, notably the Tikhvin Mother of God, an icon whose legendary peregrinations—from the paintbrush of Saint Luke to fourteenth-century Rus—include, in modern times, exile to Chicago in 1944 and repatriation to the village of Tikhvin in 2004.

Alterability has been a conspicuous feature of the icon’s modernity. Modernity here refers not simply to a series of events unfolding through an empty chronological time; on the contrary, modernity defines itself against a past that it has created in its own counterimage. As the icon took on new forms and meanings, and as it attracted an increasingly diverse array of acolytes, the boundaries of its modernity, its fateful before and after, were continually redrawn. Not only does the demarcating line between the modern and the premodern shift with each new way of seeing; the icon itself alternately falls on one side or other of this moving divide. In one view, the icon embodies tradition, both as a monument to a medieval worldview and as a bulwark against an advancing modernity. In another view, the icon partakes of a living culture, one whose rituals and outward aspect adapt to changing times, whether in line with a dominant mainstream or as a viable alternative. For one side, the icon’s modernity is a contradiction in terms; for the other, it is its ineluctable condition. Even more difficult to track are those underlying structures in the longue durée that have slowly and anonymously shaped the icon’s material culture. In this respect, those historical stretches when the icon seems to disappear from view are as significant as the dazzling and recurring spectacles of its rediscovery.

Current criticism on the concept of modernity opens further vistas for surveying the icon’s recent history. Following a standard division in the critical literature, the icon can be said to have experienced both a social modernization and a cultural modernity, each with its own subdivisions and periodization. In terms of modernization, the icon, like any other commodity in imperial Russia (1721–1917), was subject to such processes as the international flow of capital or the industrialization of production. More so than aesthetics or theology, for instance, analysis of changing media technologies across Europe helps account for the Russian icon’s remarkable material transformations—wood panels, paper prints, tin plates—from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. As a sacred object, in contrast, the icon circulates within a system of cultural or “religious” capital that is seemingly irreducible to the economic base, in a Marxist sense, or that retains a certain autonomy from what Pierre Bourdieu terms the “field of power.” This autonomy is never absolute, however. Even within the economy of the sacred, large social processes have had a demonstrable impact on the aggregate value of icons and their rituals. In particular, the Russian icon presents a compelling case study for the ongoing secularization debate in the humanities and social sciences. For Max Weber, writing in the early twentieth century, modern Western culture, through a long process of intellectualization, had arrived not so much at increased knowledge as at the “disenchantment of the world” (Entzauberung der Welt), that is, the decline of magic and mysticism as forms of substantive reason. In the Russian context, the conjunction of modernization and secularization has clear heuristic appeal, whether in relation to state campaigns to regulate or suppress icon veneration from Peter I (r. 1682–1725) to the Soviet period or in terms of the evolving views of specialists and the general public regarding the icon’s otherworldly orientation—its evocation of a divine prototype, its magical powers of protection and healing, and so on. The post-Soviet revival of Russian Orthodoxy, including the return of icons to the pageantry of state power, nevertheless exemplifies the challenges currently facing classic secularization theory. The veneration of icons, like so many traditional church practices, survives and even flourishes in modernity, appearing to disconfirm secular projections. This state of affairs lends potential support to attempts at reconceiving modernity as either “incomplete,” obsolete (postmodernity), untenable (antimodernity), or heterogeneous (multiple modernities).

Moreover, even within secular ideologies and institutions there would seem to be ample room for the sacred and the profane—the binary that Émile Durkheim considered “fundamental to all religious organization.” As icons were withdrawn from the church, literally and figuratively, new values—art, nation, the people—began to accrue to them. Although very much of this world, these values were arguably no less sacred than the Orthodox dogmas and lay beliefs that they displaced. In terms of the conventional periods of cultural modernity, perceptions of the Russian icon, from the Enlightenment to postmodernism, have changed in response to international trends in the arts and letters. Modernism in particular vastly expanded the icon’s artistic horizons. From the 1880s to the 1930s, the Old Russian icon, long neglected by a Western-educated gentry, was transformed from a parochial craftwork into a world masterpiece, from an antiquarian curio into an avant-garde aesthetic model, and from a medieval cult object into a modernist prism for seeing the world anew. The enduring success of this aesthetic revaluation is perhaps matched only by the icon’s repositioning as a national symbol. As the subtitle of our volume indicates, the modern Russian state—in its imperial, Soviet, and post-Soviet incarnations—represents the specific site of the critical interventions undertaken in the chapters that follow. For our contributors, the Russianness of the “Russian icon,” far from being taken for granted, represents a central problem for analysis. In a variation on the Romantic cult of the medieval, the icon emerged in the nineteenth century as an emblematic expression of the peasant’s traditional worldview and, by extension, the true essence of what it meant to be Russian. Especially in the wake of major upheavals—the French invasion of 1812, the 1917 Revolution, or the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union—Russia’s political and cultural elite have repeatedly conferred on the icon and its folk traditions a leading role in competing formulations of national identity.

No less important to investigate are the ways in which modernity has realigned the icon’s interfaces with the profane, both in the sense of the commonplace and the contaminating. In the latter sense, a marked anti-Western orientation can be included among the icon’s modern values. From the anti-Enlightenment sermons of clergy to the antirealist manifestos of the avant-garde, the icon’s modern defenders have sought to protect it from Western influences while at the same time defining its most authentic attributes in opposition to those same influences; at the limit of this binary logic, the icon becomes what the West is not, and vice versa. Opposition to the West does not necessarily imply an antimodern outlook, however, as if Western Europe were the sole global source of modernity, or the backward East its vast inassimilable Other. The trend in postcolonial and transnational studies over the past two decades toward “counter,” “alternative,” or “multiple modernities” offers useful models for rethinking the often contentious identity politics surrounding the Russian icon. In decoupling the West and the modern, it becomes easier to observe the formation of alternative modernities in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and even Europe. For a Western theorist such as Theodor Adorno, aesthetic modernism found much of its justification in an uncompromising critique of social modernization and its reified cultural by-products. The turn to the icon in Russian modernist aesthetics likewise represents not a retreat into the premodern but an alternative path of resistance, one in which traditional templates are not so much given as dreamed into being.

No single anthology could retrace all the winding paths of the icon in the modern period. Through a range of methods and subject matter, this volume seeks to introduce the modernity of the Russian icon as a distinct field of interdisciplinary inquiry.

Hidden and Revealed

The theme of “discovery” figures prominently in most accounts of the Russian icon’s recent history. Two events stand out in particular. The first surrounds the scientific restoration of Andrei Rublev’s Old Testament Trinity (Troitsa) (c. 1425–27) in 1904–6 (pl. 2). At the time, this icon—in which the three visitors to Abraham (Gen. 18:1–8) are depicted as a Christian allegory of the Trinity—was still housed in the place for which it had been originally painted, namely, the Trinity Cathedral in Sergiev Posad, northeast of Moscow. The icon hung on the lower left side of the cathedral’s iconostasis—the distinctive wall of icons, usually with several rows, separating the nave from the sanctuary in Eastern Orthodox churches. Rublev’s Trinity would have faced the laity during services. Yet despite its well-defined visual role in one of the holiest sites in Orthodox Russia, the icon appeared, for a certain type of viewer at the turn of the century, as if hidden from view. The icon had been repainted at least three times, while layers of protective varnish (olifa), which darkened with time, had been regularly applied over the years. Moreover, as was common for most revered icons, a gilded metal casing, or oklad, overlay most of the icon’s surface. Under the direction of Vasily Gurianov, restorers removed this gilded frame and began the painstaking task of scraping away centuries of overpaint and varnish. What they found underneath was the astonishing vibrancy of Rublev’s original colors—the light pinks, blues, and greens adorning the three figures, with bright yellow and gold replacing drab brown in the background. In a sort of secular apocalypse, a false veil of outmoded church practices had been pulled away to reveal true art, as Gurianov and his colleagues became the first moderns to see the genius of a long-neglected master, one whose name—hitherto little known beyond clergymen and antiquarians—soon attained national and international renown.

The partial cleaning of the Trinity prompted a flurry of further restoration projects, not least a hunt through rural Russia for lost and unattributed works of Rublev. Such wealthy patrons as Ilya Ostroukhov and Stepan Riabushinsky employed a new generation of ikonniki, hereditary icon painter-restorers, to work on icons in their private collections, while the church made available many icons under its control. The fruits of these combined restoration projects were presented in March 1913 at the Exhibition of Old Russian Art, which took place in the decidedly secular setting of Delovoy Dvor (literally, “business court”) near Red Square in Moscow. The exhibition introduced fifteenth- and sixteenth-century icons, cleaned and unframed, to critical acclaim as well as to a large and highly receptive public. The icons of these two centuries were presented as a uniquely Russian artistic legacy, at once distinct from earlier Byzantine models and not yet overrun by the norms of the Western Renaissance. In an influential review, the art critic Nikolai Punin wrote, “This exhibition is an event. More than that, a revelation to us all! Has not a new artistic consciousness begun in Russia?”

In retrospect, a better case could be made for considering the 1913 exhibition the final in a series of pivotal discovery events. Over the past two decades—due in large part to Gerold Vzdornov’s masterly 1986 monograph on nineteenth-century icon scholarship—the beginning of the icon’s rediscovery has been considerably pushed back in time. Long-lost murals were being unearthed in Russian cathedrals as early as the end of the eighteenth century; restoration of ancient churches in Kiev and elsewhere was under way by the 1840s; museum collections of ancient icons were organized in Moscow and St. Petersburg in the 1860s; the first exhibition devoted to ancient Russian art took place not in 1913 but in 1898; and so on. This protracted and largely unheralded process of scholarship and restoration laid the groundwork for the more celebrated turn-of-the-century rediscovery. In his review of the 1913 exhibition, Punin grudgingly grants earlier scholars priority of discovery, observing that their research found no response in the “artistic strivings of their contemporaries”: “Scholars studied, while we remained cold.” As these comments suggest, Punin and other commentators, not without some justification, distinguished the modernist rediscovery from its nineteenth-century precursors by its aesthetic emphasis. Before the 1880s, and especially during the height of realism, the art of icon painting had few apologists. Recent literary critics have pointed to the icons that adorn the classic realist novel, from A Sportsman’s Sketches (1852) to War and Peace (1869) to The Brothers Karamazov (1881). Icons also appear frequently in the genre and historical paintings of Russian realist painters in the 1860s and 1870s. Yet it remains a matter of debate the extent to which Fyodor Dostoevsky, the early Lev Tolstoy, or first-generation Itinerants (peredvizhniki) conceived of the icon specifically in aesthetic terms, let alone as an artistic model for their own work. Even Fyodor Buslaev, in his groundbreaking General Remarks on Russian Icon Painting(1866), draws on realist criteria to account for the icon’s “low level of artistic development”: “It’s as if it were afraid of reality.”

This question of precedence aside, the 1913 exhibition played an undeniable role in repositioning the icon at the forefront of Russian avant-garde art. Running parallel to the efforts of restorers, or even slightly behind (in the logic of avant-gardism), a significant number of Russian artists, critics, and poets were turning to the icon as a source of artistic inspiration. Thanks to research begun in the 1970s by such art historians as John Bowlt in the United States and Olga Tarasenko in Russia, the avant-garde’s extensive engagement with the icon is now widely recognized. For the avant-garde, the icon represented both a new myth of origins and a future horizon. On the one hand, as Alexander Rodchenko put it in 1919, “Russian art has its origin in the icon”; in other words, the Russian avant-garde traced its genealogy not to the derivative canvas painting of the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, an eighteenth-century Western import, but to an indigenous, nonrealist art form. On the other hand, in the studios of Neoprimitivist, Cubist, Suprematist, and Constructivist artists, the icon was reconceived as a paragon of abstractionism. Such leading artists as Mikhail Larionov, Vladimir Tatlin, and Kazimir Malevich, in their common cause against realism, appropriated different formal aspects of the icon, from its hieratic and free-floating figures to its flattened perspective and monochrome coloring. Natalia Goncharov’s religious compositions, including Coronation of the Virgin (1910) and Evangelists (1911), as well as her set and costume designs for the ballet Liturgy (1915) (pl. 12), proved especially provocative in their deformations of traditional Russian and Byzantine iconography. On a number of occasions, the Holy Synod, the governing body of the Orthodox Church in imperial Russia, led efforts to block the exhibition of Goncharova’s works because of their perceived blasphemy. In her iconlike paintings, Goncharova plays on the angular and anatomically irregular figures of the Virgin, saints, and angels, employing a color scheme evocative of the cleaned Old Russian icon. On this last point, she had the tacit blessing of Henri Matisse, a global authority on all things primitive, who had enthused about the “wealth of pure color” he discovered in the icons of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Despite resistance at times from the official church, the avant-garde did find fellow travelers in the burgeoning Russian religious renaissance—a revivalist movement in Orthodox theology. Evgeny Trubetskoy, Pavel Florensky, and Sergei Bulgakov, among others, contributed to the development of a critical vocabulary for understanding the Russian icon as an Orthodox alternative to the paradigms of Western visual art. As recent translations by Wendy Salmond and Robert Bird attest, Florensky’s writings, notably “Reverse Perspective” (1920) and “Iconostasis” (1921), have had an enduring impact on not just icon studies but the general field of Russian visual culture. In images organized through reverse perspective—a term coined in 1907 by Oscar Wulff—parallel lines appear to diverge from the picture plane, rather than converging on a vanishing point, as in linear perspective. In making this new term his own, Florensky expanded reverse perspective from a formal feature of Orthodox art into an indictment of the Western Enlightenment, including its positivist science and realist art. In gazing at a Russian icon, the viewer does not preside, in the “predatory and mechanical” manner of perspectival vision, over a lifeless mirror of the material world. On the contrary, the viewer submits to, and is transformed by, the beauty of a higher reality, as if the viewer were the icon’s vanishing point and the icon board heaven’s window. As for his opinions of Rublev, Florensky could not have been more anti-Cartesian: “There exists the icon of Holy Trinity by Saint Andrei Rublev; therefore, God exists.”

In sum, over the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Old Russian icon reappeared in its full glory. That restorers, artists, or exhibition visitors could rediscover the artistry of the Old Russian icon at all nevertheless says at least as much about what they were looking for as it does about what they saw. Without detracting from its importance, the cleaning of Rublev’s Trinity serves as a convenient metaphor for a far more pervasive, and multifarious, revaluation: the view of Old Russian icons as works of art. In this revaluation, the roots of which predate the modernist rediscovery, the spirit of modern science dovetailed with a no less modern artistic sensibility, as new specialists—restorers, archeologists, art historians, collectors, and curators—furnished material for the formal experiments and manifestos of artists and culture critics.

Moreover, if the Old Russian icon was a discoverable object, something whose true essence could be revealed, then this is because it had somehow disappeared from view. The notion that the icon had been long hidden pervades the writings of its modern discoverers. As in the case of Rublev’s Trinity, this disappearance could be quite literal. In “What Do Icons Teach?” (1916), the critic and writer Maximilian Voloshin describes the icon’s rediscovery as something akin to an exhumation: “Pious barbarians, who understood nothing about the beauty of tone or colors, each year covered icons with a layer of varnish. . . . Varnish was the tomb that preserved this ancient art and transported it untouched to this day.” Voloshin here pits a secular modernity against the superstitions of a backward populace. Many art historians assumed this enlightened position in relation to the Orthodox Church, which was accused of letting its own ancient icons rot and perish. As old icons darkened from soot and varnish, to the point of illegibility, clergymen were in the habit of relegating them to the status of “black boards” (chernye doski); as such, they were consigned to storage, where they could be fetched for fuel or used to patch holes in church walls.

In a 1930 article, Alexander Anisimov, a leading Soviet icon scholar, argued that the task for his field was “to establish on a really scientific basis, chronologically dating for the main periods, the history of Russian Icon-Painting, its bloom, its over-refinement, and, finally, its decay.” Crucial to that task was the need to save Old Russian icons from the church. The institutions responsible for the icon’s storage, maintenance, study, and valuation indeed underwent a profound secularization, in a very literal sense, as control over the most ancient of Russian icons passed to a new class of secular priests (cleris sæculum). The migration of icons from churches to museums was already well under way by the reign of Nicholas I (r. 1825–55). In the wake of the 1917 Revolution, when the new Soviet government began to seize church lands in a systematic manner, this migration became a rout. Rublev’s Trinity, for example, was relocated to the Tretiakov gallery in 1929, where it still remains. For the Orthodox Church, the icon had been an object that could be cleaned, repainted, encased, and even destroyed, all according to codified rituals. The application of varnish took place annually on the first Sunday of Lent, while in the wake of the seventeenth-century schism in the church, elaborate and austere public ceremonies were developed for defacing and burying icons that failed to conform to newly instituted iconographic standards. In the church, the icon is sacred, yet not of its own power; rather, what infuses the icon with sacred value is the absent prototype it evokes. In the museum, by contrast, the body of the icon itself becomes inviolate, subject to rituals of preservation no less sacred for being secular. These rituals serve to set the icon apart from the profane circulation of everyday goods. Whereas old churches generally went unheated, the icons’ new environment was carefully controlled for light, humidity, and temperature. It was likewise necessary to remove the profane traces of the icon’s material history, so as to restore it, inasmuch as this was possible, to the authenticity of its original created state. In the museum, the value of icons depends less on the identity of their holy figures than on that of their creators, whether “the people” (narod) at large, particular schools, or, more rarely, individual artists—artists whose names curators and art historians often took great pains to ascertain.

Other scholars attributed the modern disappearance of the Russian icon to the invidious effects of Western influence. In his authoritative Russian Icon (1927), Nikodim Kondakov writes that “two centuries of neglect, beginning in Peter’s time, have sundered the Russian people from the last flourishing period of icon-painting and destroyed a greater number of examples than all the town fires or devastations of the countryside.” Kondakov, writing from exile in Prague, attributed the decline of icon painting from the late seventeenth century onward to the increasing Westernization of educated Russian society, of whom the clergy represented only one small part. Suffering from an “excessive admiration of everything Western,” educated Russians “ceased to care for [icons], forgot them, and no longer looked after them . . . they were put away into store.” This culpable neglect affected even where icons were made. Icon painting, once centered in Moscow and Novgorod, “hid itself in the depths of the Russian countryside,” that is, in the towns of Palekh, Kholui, and Mstera in the Vladimir province, where the icon, once a high art form, had degenerated into a “handicraft or kustar' product.”

Most important, the educated elite—with certain noteworthy exceptions—failed to protect the art of icon painting from the corrosive influence of the Renaissance. From the end of the sixteenth century onward, the Russian icon gradually began to lose its aesthetic purity. In churches and the homes of the aristocracy, icons took on naturalized figures, darker hues, decorative flourishes, and rudimentary elements of perspective. In describing such icons, Kondakov uses the common term “Frankish” (friazsky), a style he criticizes as an “unsatisfactory compromise” between “late Greek” and “Western art.” For the twentieth-century theologian Leonid Ouspensky, such Western stylistic corruptions are inseparable from an underlying “secularisation of religious consciousness”: “In the XVIIth century the decline of Church art sets in. . . . Loss of the consciousness of the dogmatic meaning of art inevitably led to the distortion of its very foundations and no artistic gift, no exquisite technique proved able to replace them.” The icon’s long “neglect” (Kondakov), “decline” (Ouspensky), or “decay” (Anisimov) reaches its nadir only in the nineteenth century. Yet on both aesthetic and theological grounds, the Russian icon’s earlier exposure to the Western Renaissance set in motion this tragic fall into modernity.

A double chronology of hiding and revealing thus underlies the logic of the icon’s modernist rediscovery. Modernism made possible the widespread recognition of the Old Russian icon as an art form. By the very terms of aesthetic modernism, however, the modernity of the icon would seem to have begun much earlier. One set of modern forces—secular scholarship, the science of restoration, avant-garde aesthetics—precipitated the recovery of a lost artistic patrimony. Yet a second set of modern forces—Westernization and a secular disregard for native religious traditions—had resulted in its long hiding. Most classic monographs on “the Russian icon”—Rovinsky (1857), Kondakov (1928–33), Lazarev (1983)—do not extend past the seventeenth century. This volume begins where the standard historiography of the Old Russian icon ends. Between these two chronologies, in the period of the icon’s supposed neglect and disappearance, lie important yet understudied chapters in the icon’s modernity.

Icon and Identity

From the point of view of cultural practice, it is hard to imagine an object less in need of discovery than the icon in imperial Russia. For the Orthodox and non-Orthodox alike, icons were everywhere. As the pioneering icon scholar Ivan Snegirev explained in an 1862 article, holy faces, watching over the faithful from the cradle to the grave, were always in the visual field: at church, at home, at work; on city gates and bridges; in the marketplace; interceding for soldiers on land and at sea; presiding at births, marriages, and deaths; and mediating family disputes. More recently, Oleg Tarasov, in his cultural history Icon and Devotion(1995), has underscored the challenges that the “burden of numbers” poses for the study of imperial-era icons, millions of which were produced annually from the mid-nineteenth century onward in Palekh, Kholui, and Mstera: “It seems certain that in no other place or period was icon production so massive.” These imperial icons may not have fit as well as their Old Russian predecessors in modernist canons of art history; yet at the time, their mass production ensured a constant rate of replacement at levels that more than made up for any loss of aging models. By their near ubiquity, icons cast a sacral veil (pokrov)—to borrow a familiar symbol of intercession in Mother of God icons—over everyday life in imperial Russia.

This veil did not extend evenly to all corners of the empire, however. In the wake of the iconoclastic controversies of the eighth and ninth centuries in Byzantium, icon veneration was affirmed in Orthodox dogma as a requirement for all members of the true church. In imperial Russia, the icon continued to confer the sign of Orthodoxy on those who venerated it. In her research on Russian Orthodoxy in the prerevolutionary period—the “largest Orthodox culture of modern times”—Vera Shevzov makes the compelling case that icon veneration, even more so than attending mass or receiving the Eucharist, played a dominant role in fostering an “ecclesial identity” among the laity; thus peasants in rural areas who might not step inside a church for years at a time or see a bishop once in their lifetime identified with the sacred community of the church by means of icons. In an Orthodox household, one or more icons were generally placed in the so-called beautiful corner (krasnyi ugol) of the main room, ideally on a small, elevated shelf facing the entrance from the east and lit by a prayer candle. At the same time, homes that lacked an icon corner bore the mark of its absence. The non-Orthodox included “those of other faiths” (inovertsy)—Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, members of polytheistic religions—as well as dissenters, such as the Dukhobors and Tolstoyans, who in rejecting icons as idolatry rendered manifest their break with official Orthodoxy. The role of the icon in identity formation extended as well to rites of inclusion and exclusion at the threshold between the Orthodox and the non-Orthodox. Thus missionaries incorporated icons in the baptismal ceremonies of new converts at the far reaches of empire, while as part of an annual rite commemorating the Orthodox victory over the iconoclasts, anathemas were proclaimed in parish churches, not least against those who, in old ways and new, mock or profane holy images.

Through prayers, blessings, hymns, and other rituals, all subsections of the Orthodox community, from the tsar and the Holy Synod to the vast peasant laity, participated in the veneration of icons. Yet different constituent groups identified with the icon for different reasons, not all of which had Orthodoxy as their foremost concern. In sermons and ecclesiastical writings, local and national clergy, in endless variations on the same theme, promulgated the incarnational theology adopted at the Seventh Ecumenical Council in Nicea (787); just as the Word became flesh (John 1:14), so, too, holy beings or “prototypes”—Christ, the Mother of God, and the saints—may be legitimately venerated through their human likeness in icons. To confuse the image for its prototype constitutes idolatry, that is, the worship of graven images (Exod. 20:4–5), while to pray before the wrong kind of image borders on heresy. The ability of the church to police correct usage was nevertheless limited in practice. In Likeness and Presence, Hans Belting argues that Christian traditions of image veneration, both Catholic and Orthodox, ultimately derive from popular rites foreign to the “church’s institutions”; theology, at first unable to ban the people’s favorite cult images, instead settles “for issuing conditions and limitations governing access to them.” Be that as it may, the Russian Orthodox Church remained a relatively decentralized institution in the imperial period, with standardized rites supplemented by a patchwork of local practices. Thus individual parishes tended to have their own “revered” (osobochtimye) icons, icon processions, and favored saints, and while the laity did look to the clergy to consecrate any new “miracle-working” (chudotvornye) icons in their midst, the church lacked a single standard for adjudicating all claims, and official disapproval did not necessarily curb rumors surrounding a popular icon’s magical appearance or healing powers.

Under Peter I (r. 1682–1725) and his successors, the church hierarchy, motivated in part by an Enlightenment distrust of superstition, struggled to contain the sacred within officially approved channels, confiscating nonsanctioned icons, submitting miracle-working icons to empirical tests, and blocking the veneration of church icons in public spaces. During the course of the nineteenth century, official responses to popular forms of icon veneration nevertheless became gradually more accommodating. As Shevzov observes, church intellectuals, in Russia and elsewhere, were actively relocating the institutional center of their respective sacred communities in the “people”; as Patriarchs of the Eastern churches explained to Pope Pius in an 1848 encyclical, “Neither Patriarchs nor Councils could introduce novelty among us, because the protector of religion is the very body of the Church, the people themselves.” In Russia, this conceptual shift toward the peasant laity, as formulated by both secular and clerical authorities, contributed to a fin-de-siècle flourishing of popular rituals and legends involving icons. Thus the number of rural icon visitations, in which revered icons are led from church to church or to private homes, measurably increased, while prominent church leaders, offering their protection and theological support, often welcomed reports of new miracle-working icons beyond the few dozen that the Holy Synod officially recognized.

Top-down campaigns to regulate icon veneration, in contrast, had a mixed record at best. From 1653 to 1656, to note a major example, Patriarch Nikon of Moscow, with the approval of Tsar Alexis I (r. 1645–76), forced through a number of liturgical revisions in an attempt to bring Russian practices in line with Greek Orthodox models, including on matters of iconography. Thus the spelling of Jesus’ name on icons was changed from Isus to Iisus, and the number of fingers used in making the sign of the cross increased from two to three. At church councils in 1656 and 1666–67, those who refused to support the revised rite—and its accompanying iconography—were anathematized, a judgment that the state backed with force of arms. This combined front nevertheless failed to prevent, and even arguably accelerated, the formation of independent “Old Believer” churches (as the dissenters came to be collectively known). Under Nicholas I (r. 1825–55), state authorities redoubled their efforts to suppress Old-Believer practices, in the process confiscating large numbers of “heretical” icons from before and after the schism. Yet by the mid-nineteenth century, the fate of Old Believer icons was no longer exclusively a matter of church and state. For a small group of scholars and private collectors, Old Believers had performed an invaluable national service not only in protecting pre-Nikonian icons from official acts of iconoclasm but also in continuing to paint new icons using the methods and iconography of the “old style.” Wealthy Old Believers discretely amassed private icon collections, and scholars of varying religious persuasion relied on Old Believer sources to rewrite the sacred history of the icon along national and secular lines. Even within the government Old Believer icons found allies; thus, instead of being ritually destroyed, as had been the norm two centuries earlier, many confiscated icons from the Ministry of Internal Affairs ended up in state museums.

For all sides concerned, a national reframing of the icon’s significance furnished common ground for a new connoisseurship. At a pragmatic level, discussion of the schism remained tightly censored. In Dmitry Rovinsky’s Survey of Icon Painting in Russia Through the End of the Seventeenth Century (1856), for instance, the first general monograph of its kind, religious censors expurgated all references to Old Believers. Yet in a larger sense, a unified national narrative—one grounded in a common valorization of Russia’s folk heritage—displaced an otherwise still very real controversy over exclusive icon traditions of the Old Believers and the official church. In terms of semantics, “Russian” (russkoe) and “old Russian” (drevnerusskoe) emerged as master qualifiers for “the icon” (ikona or obraz) in publications and exhibitions, a development no less significant than the prevalent substitution of “art” (iskusstvo) and “painting” (zhivopis') for “icon painting” (ikonopis') a half century later. In 1905, after an edict on religious tolerance permitted Old Believers to open their churches, fresh caches of pre-Nikonian icons were made public and restored by specialists. The 1913 Exhibition of Old Russian Art not only brought together icons from both sides of the schism; neither “Orthodox” nor “icon” even appeared in the exhibition title.

The 1913 exhibition, which was enthusiastically supported by Nicholas II (1895–1917) and proved a highlight of the celebrations for the Romanov dynasty’s tercentenary, also illustrates the role of the state in nationalizing the icon. This role can further be tracked in relation to Ukrainian Church art. The Russian and Ukrainian branches of the Orthodox Church, both descended from Kievan Rus, had for nearly two hundred years existed independently prior to the Russian acquisition of eastern Ukraine in the 1620s–1640s. Among the precipitating causes of Nikon’s liturgical reforms had been the need to harmonize Moscow’s liturgy with that of the Ukrainian Church. Inasmuch as they were thought to resemble Greek models, Ukrainian icons ended up on the opposing side of the schism from those defended by predominantly Russian Old Believers. Despite the official favor that the Ukrainian liturgy enjoyed following the schism, decisions affecting Ukrainian churches were increasingly made by state authorities in Russia. In 1686–87, the Kievan Metropoly became subordinate to the Moscow Patriarchate, while in 1721, Peter I abolished the Moscow Patriarchate and replaced it with the Most Holy Governing Synod in St. Petersburg, the new imperial capital, effectively rendering the Orthodox Church a department of the state. By the mid-nineteenth century, as in the case of Old Believer icons, the restoration of Ukrainian churches in Kiev was contributing in significant ways to a growing appreciation of icons in Russia. In the fall of 1842, Nicholas I visited the Monastery of the Caves (Pechers'ka lavrato) in Kiev to inspect frescoes in the eleventh-century Dormition Cathedral, which recently had been repainted under the auspices of the Kievan metropolitan. Unhappy with what he saw, the tsar ordered that all church renovations henceforth be approved by the Holy Synod. As Vzdornov notes, the tsar’s displeasure, for better or worse, marked a key moment in the transition from repainting to restoration in the empire. With Nicholas I’s approval, Fyodor Solntsev, a Russian painter from the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, employed secular techniques in the restoration of the Dormition Cathedral and, shortly thereafter, the even more ancient and revered Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev.

Under Nicholas I, “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality”—a formula developed by Sergei Uvarov, his minister of education—became the official doctrine of the Russian Empire. A coincidence of Orthodoxy and nationalism, on one hand, and the collaboration of state, church, and academy, on the other, can be observed in many church commissions at the time. For major construction projects, the Holy Synod generally turned to academy-trained painters (zhivopistsy), who enjoyed a higher level of professional prestige than did traditional icon painters (ikonopistsy) from Palekh, Kholui, or Mstera. In two prominent cases—Saint Isaac’s (1818–58) and Christ the Savior (1838–81), the largest cathedrals in St. Petersburg and Moscow, respectively—teams of academy painters applied Western-style religious painting more or less directly onto the walls of Orthodox churches. By contrast, in a Russian iteration of Pre-Raphaelitism, the focus toward the end of the century noticeably shifts from the Renaissance to Byzantium. Thus Viktor Vasnetsov studied Old Russian icons as well as the Byzantine frescoes and mosaics of Rome and Istanbul in preparation for designing the murals of the Saint Vladimir Cathedral in Kiev. Built from 1885 to 1896, this cathedral was commissioned to commemorate the nine-hundredth anniversary of the conversion of Rus to Christianity in 988 under Vladimir, Grand Prince of Kiev and a canonized saint (pl. 8). Vasnetsov lent visual form to an official reading of church history that positioned Russia as the rightful heir to Kievan Orthodoxy, the first church of the East Slavic peoples, and he himself emerged as the leader of a reform movement within Orthodox iconography, as his Byzantine-inspired murals were widely reproduced in lithograph form and in other churches.

In short, those branches of Orthodoxy that were nonconforming (Old Believers), non-Russian (Ukraine), or even pre-Russian (Byzantine) were to varying degrees assimilated into emerging narratives about the Russian icon. Despite the central role assigned to the Russian people in such narratives, the church and the intelligentsia nevertheless maintained a certain ambivalence toward popular means of icon production. In his 1866 monograph, Buslaev praises the “artistic ideals” of the traditional Russian icon painter, an ascetic folk figure who does not “consciously strive toward refinement” or “artificial poetry”: “in such ideals . . . the Russian people expressed its understanding of human worth.” These same ideals had enabled Russian icon painters, at least until the seventeenth century, to “remain true to Byzantine traditions”: “our ancient icon painting has the indisputable advantage over Western art inasmuch as fate guarded it . . . from that artistic upheaval commonly known as the ‘Renaissance.’” Traditional icon painters appeared to have accomplished this extraordinary feat of preservation through an ethos of similitude: the icon reveals the likeness of its prototype; new icons, as copies of copies, preserve that likeness by transcribing it from other icons. For midcentury icon scholars across Europe, research on Greek icon-painting manuals and Russian pattern books (podlinniki), which provided verbal or pictorial schemas for canonical holy figures, further explained the perceived stylistic continuity of the Eastern icon over the centuries and across the Orthodox world. In Russia, where pattern books were still in use, the 1869 publication of the pre-schism Stroganov podlinnik had the telling, if unintended, consequence of reinforcing a growing stereotype of the icon painter as a mere copyist. In Leskov’s The Ensealed Angel (1873), a popular novella about a desecrated Old Believer icon, one icon painter pointedly rejects such a view: “It’s an offense to us to think that we simply use set patterns as if they were stencils. In the pattern book [podlinnik], we’re given a rule, but how it’s followed is left to the freedom of the artist.”

As these comments suggest, a reliance on sanctioned models seemed at odds with the criterion of originality dominant in secular canons of high art. Elizabeth Valkenier, for example, observes that first-generation peredvizhniki painters, for all the populism of their subject matter, did not borrow from such peasant art forms as the lubok, a type of woodcut used for making anything from domestic icons to shop signs. Indeed, lubochnyi(“lubok-like”) served as a derogatory term for coarse art among professional painters and critics. In a similar manner, as Robert Nichols has shown, icon scholars and enthusiasts from Moscow and St. Petersburg tended to be appalled at the ominous signs of mass production they found on visiting provincial icon centers. In order to keep up with overwhelming demand, icon painters in Palekh, Mstera, and Kholui were increasingly forced to sacrifice individual craftsmanship in favor of a collective division of labor; in a given workshop, where the underpaid workers often included women and children, each icon was constructed in a piecemeal fashion, passing from one station to the next. In a 1901 report “on the contemporary state of Russian folk icon painting,” Kondakov laid out for Nicholas II the extent to which the craft of icon painting had deteriorated due to the ignorance and poverty rampant in such workshops. Even worse, foreign firms in Moscow were producing tintype icons by means of metal presses and chromolithography, a practice that Kondakov and his allies subsequently campaigned, without success, to have banned. In the age of mechanical reproduction, the painting of Western Europe confronted its perspectival double in the photograph; the icon, a sacred copy, instead attained a sort of reductio ad absurdum in the canning factories of Moscow.

On the eve of modernist rediscovery, the art of icon painting, for a small but influential minority, was in desperate need of revival. The diverging fates of the Old Russian icon and the imperial icon were inextricably linked at the turn of the twentieth century. The cultural elite celebrated the folk traditions of the first, even as they abhorred the means through which the second was made available to the masses. Five years after Kondakov’s report, Gurianov, an award-winning icon painter in his own right and a fellow proponent of the craft’s revival, published the results of the cleaning of Rublev’s Trinity. Upon removing the icon’s metal casing, and before witnessing Rublev’s underlying colors, Gurianov recounts his “surprise” at the sheer artlessness of the overpainting: “We saw an icon painted in the new Palekh manner of the nineteenth century.” In the landmark restorations of Old Russian icons, not only did the hidden become revealed, but something that had been everywhere visible became unworthy of view. The imperial icon was the first layer modernism scraped away.

Reframings

The meaning of the icon depends on its contexts. These contexts include the spaces in which icons reside and move, the processes of production and maintenance they undergo, as well as their discursive environment—the words written about them, spoken in their presence, or inscribed on their surface. On the importance of language in particular, semiotics concurs with theology. Boris Uspensky and Leonid Ouspensky, in otherwise very different monographs, both emphasize the writings of the Church Fathers in constituting the icon’s meaning and content. The icon’s potential for meaning is nevertheless not foreclosed by any single interpretative structure, be it a body of dogma or a system of signs. On the contrary, the removal of old frames clears the way for new ones. With a shared attention to dynamic processes, as well as a critical orientation toward one-sided narratives of loss, the authors in Parts I and II of this volume explore the changing meaning of icons in their modern contexts.

In a chapter on Mother of God icons, Elena Boeck brings fresh insight and theoretical sophistication to the long-standing problem of the Russian icon’s relationship to Western images. As Boeck demonstrates, cross-cultural exchanges proved conducive to the production of entirely new iconographic types. At the turn of the eighteenth century, disparate images of Mary from across Christendom—which were making their way to the Russian market via print media—laid the foundation for the emergence of compendia icons, a type unknown to earlier Byzantine iconography. In such icons, multiple miniature miracle-working icons are displayed in a well-ordered grid, each icon labeled to indicate its provenance. Such an arrangement, in its concern for cataloging and universality, betrays a taxonomic impulse typical of the Enlightenment. As modern innovations, Russian compendia icons are not intended to be perceived as miraculous in themselves; rather, their purpose is to affirm existing traditions of miracle-working icons. As Boeck argues, the first compendia icons appear to have participated in eighteenth-century campaigns against the church reforms of Peter I, including his efforts to put purportedly miracle-working icons to the test. By the end of tsarist Russia, in contrast, the compendium icon had fully entered the Orthodox mainstream, becoming a patriotic expression, officially sanctioned, of Russia’s favored status beneath the Mother of God’s veil.

Vera Shevzov pursues this emphasis on the politics of tradition within church liturgy, documenting the modern evolution of the annual celebration of icon veneration on the first Sunday of Lent, a feast day known as the Triumph of Orthodoxy. As Shevzov argues, icons are framed not only materially but also rhetorically, that is, according to the sacred language of liturgy. Since its inception in ninth-century Byzantium, the liturgical rite that was conducted for the occasion of this feast linked icons with the “triumph” or “victory” of the Orthodox faith. It did so by reiterating the incarnational theology on which the veneration of icons was based; by remembering those who defended images and this theology; by condemning iconoclasts and their views; and by lauding the emperor and patriarch or local bishop as the defenders of Orthodoxy. In the mid-eighteenth century, church officials streamlined and standardized this rite in order to make its celebration uniform throughout Russia. Reading these revisions in light of the modern account of the icon’s history, Ouspensky concluded that the new rite obscured the confessional content of the icon, thereby reflecting the general decline to which the icon in modern Russia was subject. Through close analysis of the modern celebration of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, Shevzov maintains instead that while the content of the new rite did indeed focus less on the icon, it did not lose sight of it. Rather, the icon’s theological meaning was liturgically recast, enabling latent meanings to come into relief.

In a chapter on Nicholas II, Robert Nichols extends this focus on icon traditions to the imperial court. Specifically, Nichols demonstrates that the last emperor’s abiding preoccupation with miracle-working icons, far from representing a political anachronism, as has been commonly argued, contributed to a well-crafted national persona. As a future head of the church, Nicholas had been raised as a child with an appreciation for all forms of liturgical worship, and throughout his life he maintained a belief in the miraculous powers of icons. Nichols situates the tsar’s iconophilia within the context of an emerging twentieth-century aesthetics of power, one in which the cult of the medieval served as a thoroughly modern alternative to competing ideologies based on the principles of the Enlightenment. This synthesis of the old and the new is especially evident in Nicholas II’s behind-the-scenes involvement in the canonization of Saint Seraphim of Sarov, an early nineteenth-century elder (starets), whose freshly minted icon the tsar used to bless Russian troops as they departed for war with Japan in 1904. In keeping with his national persona, Nicholas also endorsed efforts to revive the traditional art of icon painting. For Nicholas and Alexandra, icons, particularly those of warrior saints, harked back to an earlier era when the tsar and the people were spiritually united, and thus embodied the faith, military strength, and established order key to Russia’s continued greatness.

Nicholas II’s new synthesis did not survive his reign, of course. After the collapse of the Romanov dynasty in 1917, control over pre-Petrine icons shifted decisively from the church to the museum. Shirley Glade, John-Paul Himka, and Wendy Salmond explore the causes and consequences of this process from three different starting points. In a chapter on Alexander Anisimov, Glade selects the work of a single scholar-champion (uchenyi-borets) to highlight the high stakes surrounding the rediscovery of the Russian icon in the first decades of the twentieth century. As a scholar and one of the founders of the Soviet science of restoration, Anisimov was an early and outspoken proponent of the view of Old Russian icons as artistic masterpieces. In 1912, he launched the first public attack on the Orthodox Church for its mismanagement of the icons in its care. Just a few years later, Animisov found himself fighting instead the indiscriminate iconoclasm unleashed by the revolution. In 1918, Anisimov was appointed scientific director for the newly founded Commission for the Preservation and Uncovering of Monuments of Ancient Painting. Thanks to the nationalization of church holdings in the 1920s, he and his colleagues gained unprecedented access to the most ancient icons in Russian cathedrals. Through numerous publications, Anisimov was instrumental in rewriting the history of the Russian icon and, by extension, Russian painting. Perhaps his single greatest feat was the restoration and scientific dating of the Vladimir Mother of God, among the first icons to reach Russia from Byzantium. While Anisimov’s thoroughgoing secularism may have corresponded well to the spirit of times, he eventually fell victim of Stalin’s purges, and his name was virtually forgotten.

In a chapter on the National Lviv Museum, John-Paul Himka chronicles the hundred-year history of a major icon collection against the background of recurrent political upheaval. At the time of the museum’s founding in 1905, the destruction of aging icons was commonplace in Catholic churches in Galicia. For such iconophiles as Andrei Sheptytsky, the archbishop of Lviv, it was a matter of great urgency to seek out endangered icons and place them under the auspices of the new museum. Like the city of Lviv itself, which was ruled successively by Austria-Hungary, Poland, Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and independent Ukraine, the museum found itself in the continual crossfire—at times literally—of opposing ideological forces. The shifting political landscape influenced everything from the makeup of the curatorial staff, many of whom suffered arrest and exile, to the location of the museum’s collection, a subject of bitter dispute as recently as 2005. Despite such hardships, secular scholarship on the icons of Galicia flourished at most stages of the museum’s existence. Himka’s research on the museum’s Ukrainian Catholic icons offers suggestive parallels for rethinking the museum collections of Orthodox icons elsewhere in the former Soviet Union as well. As with the Russian icon, the reconceptualization of the Ukrainian icon from sacred image to folk art proved amenable to Communists and nationalists alike, helping the museum’s collection outlive the regimes around it.

Among many other points of contact, Himka and Glade—focusing on a single scholar and a single museum, respectively—each chronicle the immense and protracted labor required to effect a revaluation of the medieval icon, which saw its perceived artistic worth rise slowly but steadily over the early decades of the twentieth century. In a chapter on the traveling exhibition “Masterpieces of Early Russian Painting,” Wendy Salmond follows this process of revaluation to its logical conclusion, examining how Soviet scholars, including Anisimov, repackaged the icon for the global art market. Working in conjunction with the State Trading Agency (Gostorg), Soviet icon scholars and restorers organized the first-ever exhibitions of Old Russian “painting”—that is, zhivopis', a term preferred to ikonopis' or “icon painting”—in Western Europe and the United States. Igor Grabar, the guiding force behind the enterprise, conducted numerous interviews with the foreign press, while the exhibition catalog showcased Soviet advances in the science of restoration. Focusing on the American stage of the tour in 1930–32, Salmond makes two provocative claims about the exhibition’s aims and results. First, its hidden agenda was to raise hard currency for the cash-strapped Soviet state by instilling an appreciation for the icon as a fine art in bourgeois collectors. Second, the exhibition version of the Russian icon’s rediscovery became the dominant narrative in the American academy. Ironically, as Salmond documents, the exhibition failed in its mercantile mission. In a larger sense, however, the exhibition did succeed in securing a permanent place for the Russian icon on the world stage. Salmond provides a timely genealogy of the international study of the Russian icon.

Since the seventeenth century, myriad ideological forces have been brought to bear upon the icon, from Enlightenment taxonomies to anti-Enlightenment anathemas and from an imperial cult of the medieval to a Soviet cult of science. In the process, the meaning of the icon has been repeatedly reframed: old icons must be restored, not repainted; preserved for posterity, not put to ritual death. Most crucially, the icon, once within the walls of the museum, becomes a painting, a work of art, even a masterpiece. Looking back, with whatever blind spots and vantage points such hindsight makes possible, the aesthetic value of the Old Russian icon, rather than representing the rediscovery of something long neglected and then rediscovered, can be recognized as modernity’s own seal of authenticity.

Intermedial Icon

Not only did Russian icons acquire new discursive frames in modernity; they also changed medium. In Icon and Icon Veneration (1931), to cite a telling example, the theologian Sergei Bulgakov transforms the icon into a new phenomenology by way of film: “In a lifetime, a person manifests an innumerable number of icons of his spirit, unfolding the endless film reel of his phenomenology.” For Bulgakov, the human form is like an icon, while the icon, in turn, is like a moving image (as opposed to a static portrait). Setting aside the intricacies of Bulgakov’s incarnational theology, his conjunction of icon and film here and elsewhere in his writings is symptomatic of a fundamental shift in the understanding of what constitutes an icon. In modern art and criticism, the notion of the icon began to refer not just to a certain type of holy image depicting the set figures of Christian iconography, one made by church-sanctioned producers and consecrated as worthy of veneration for the faithful. In addition, icons, whether whole or in part, readily morphed into word pictures, paintings, posters, photographs, and stage sets. They were projected on film, in dreams, from the retina of the eye, or, as in Bulgakov, into the recesses of the soul.

Beginning in the nineteenth century and culminating in the art of the avant-garde, the icon emerged from a long-standing, if only ever relative, artistic isolation and entered into an ever-widening scope of intermedial contacts with the secular arts. Intermediality, a term that has gained currency in word/image studies, can be defined as the network of relations, both internal and external, connecting cultural productions of one medium with those of others. In the case of the icon, its appropriation by other media could result in an eclectic syncretism or a totalizing synthesis (Gesamtkunstwerk), depending on the artist in question. Yet whether an artist accented or effaced its otherness, the Russian icon, in its new media, became both more and less than what it had been before. The authors in Parts III and IV of this volume critically examine the aesthetic and ideological ramifications of the icon’s protean intermediality in modernity.

Jefferson Gatrall explores the different ways that late nineteenth-century Russian writers and painters attempted to modernize the iconography of Christ, tracking in particular a convergence of scholarly and artistic projects over the field of early Christian iconography. In preparation for his painting Christ and the Adulteress(1887), Vasily Polenov consulted catacomb frescoes as well as Byzantine icons and miniatures in a quixotic effort to reconstruct the physical appearance of the historical Jesus—a conspicuously modern Christ type. Polenov’s work parallels that of the archeologist Dmitry Ainalov, who in the 1890s conducted firsthand research on Byzantine mosaics in Italy, where, among other things, he singled out a fourth-century blond-haired, blue-eyed Christ as the oldest extant instance of the “historical type.” In the novel Julian the Apostate (1896), by contrast, Dmitry Merezhkovsky’s fourth-century protagonist, the last pagan emperor of Rome, encounters a host of Christ images from Constantinople to Cappadocia, none of which captures whole the true Face and yet all of which carry a potential trace of its original meaning. In different media and with disparate results, Polenov, Ainolov, and Merezhkovksy thus each extended the nineteenth-century quest of the historical Jesus to an updating of the iconography of Christ. In the process, they modernized the traditional link between an icon and its prototype: the true likeness of the historical Jesus, inasmuch as it is recoverable at all, must be sought in his earliest surviving afterimages.

In contrast with this iconographic focus, typical for nineteenth-century scholars and artists, the Russian avant-garde appropriated the icon’s formal properties to an unprecedented degree. In her chapter, Sarah Pratt detects and analyzes “invisible icons” embedded in select poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky, Velemir Khlebnikov, and Nikolai Zabolotsky. These icons are not legible on a cursory reading yet emerge from within the visual logic of each given poem. Moreover, different poems encode quite specific icon types—Christ Pantocrator, Our Lady of the Sign, and so on—without, however, being just poems about icons. In other words, none of these poems are ekphrases. Instead, they preserve the intermedial otherness of the icon through a complex semiotic operation. Borrowing Charles Sanders Peirce’s terminology, Pratt analyzes how each poem, as a “symbol” or third-order sign, both obscures and reveals the presence of an imaginary icon; that is, a first-order sign. This icon, as if buried beneath layers of text, forms one part of a “mixed-media palimpsest”; thus the poem does not cancel out its own semiotic thirdness but rather expands to accommodate the firstness of the icon. The reader, as an “interpretant,” is transformed into a viewer and, in an Orthodox sense, even a supplicant. At the same time, these invisible icons serve thoroughly heterodox purposes, whether to glorify Soviet Man (Zabolotsky), poetic language (Khlebnikov), or the poet himself (Mayakovsky).

Unlike traditional icon painters, who worked as members of the church, avant-garde poets and painters of iconlike art, whatever their individual belief systems might be, remained secular producers. Pavel Florensky, priest and polymath, worked from the opposite direction, bringing theology into dialogue with profane realms of knowledge in order to reconcile the icon’s dual claims as art form and sacred object. Douglas Greenfield and John McGuckin both situate Florensky’s theory of icons in relation to understudied aspects of his life and writings. Greenfield takes up Florensky’s philosophy of technology. Connecting Florensky’s thoughts on such eclectic topics as Aegean archeology, the physiology of the eye, puppet theater, and even Siberian permafrost, Greenfield sheds light on the neglected material substratum of Florensky’s theological interpretation of reverse perspective. For Florensky, tools not only reflect, as symbolic reagents, a given culture’s worldview; they also represent organ projections, literal extensions of the body. Florensky tellingly demonstrates the dual aspect of the symbol-tool in relation to a recently discovered binocular-shaped vessel from ancient Crete. In Florensky’s view, this symbol-tool belongs to the cult of a female deity and simultaneously evinces an advanced awareness of binocular disparity. As Greenfield argues, the icon, as a symbol-tool in its own right, expresses a similar awareness of the disparity between the images received by each eye. In his essay “Reverse Perspective,” Florensky contends that Western painting, in its dependence on linear perspective, presupposes a monocular worldview. By contrast, the icon, which integrates multiple perspectives on a given object over time, remains faithful to the doubleness of human vision, a superiority with both symbolic and technological consequences. The icon, as the projection of two eyes, not one, is a powerful tool for suprasensual perception.

In his chapter on Florensky’s theory of dreams, McGuckin makes the provocative claim that Florensky himself, through the totality of his words and deeds, represents both an icon and its commentary. In keeping with his own understanding of Divine Wisdom as a cosmic unity in diversity, Florensky undertook a personal journey through the empirical and theoretical sciences—from mathematics to art history to linguistics and beyond—in search of a synthetic worldview that could accommodate the heterogeneity of the material world. These studies, moreover, were inseparable from his vocation as an ordained priest. Even after the revolution, when he was forced to give up his position in the church, he remained a conspicuous witness to the spirit of ecclesiality, wearing his cassock to scientific lectures and even at party meetings. As McGuckin argues, this liminality, straddling the secular and the clerical, the spiritual and the material, also informs Florensky’s understanding of the icon. In his essay “Iconostasis,” Florensky, through the concept of iconic dreaming, presents an arch-psychoanalytical interpretation of dream to illustrate the liminality of icons. As in a dream state, the icon painter, in an ascending moment, enters an imaginary space in which the visible and invisible, the phenomenal and the noumenal, coexist. It is only in the descent toward waking, however, that the dreamer/icon painter, passing back across the threshold, lends revelation the form of symbolic imagery. The icon, indeed all true art, is materialized dream.

In the final chapter of this volume, Robert Bird emphasizes the circumspection with which Andrei Tarkovsky approached the icon in his 1969 film Andrei Rublev. In his writings, Tarkovsky does identify certain formal qualities common to film and the icon: both are imprints of absent originals, whether a negative image or a divine prototype; both are torn between the demands of image and narrative. At the same time, however, film is an utterly profane art form. As Tarkovsky observes, film was born at the fairground, and there is a long tradition of desecrating icons in Soviet cinema. Any attempt to capture icons on film runs the double risk of either profaning or aestheticizing the sacred. Tarkovsky instead uses the medium of film, as both narrative and image, to illuminate the religious significance, common to all sacred arts, of aesthetic experience. In Andrei Rublev, icons remain passive, background objects in the narrative of Rublev’s life. This narrative, though profane, nevertheless crucially situates his icons in the material world and provides occasion for their presence to become manifest—most paradoxically, in scenes where they are destroyed. Through the pauses in the fragmentary narrative of Andrei Rublev, Tarkovsky thus pushes film toward a transcendent image of that which must ultimately lie beyond its own grasp. The “celluloid icon,” as Bird puts it, does not replace the icon but rather marks the break where film, in a gesture of intermedial sacrifice, cancels itself out.

In the six decades between the cleaning of Rublev’s Trinity and the making of Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, the icon became a model of color and perspective, of human vision and the human visage, for the secular arts in Russia. Just as any backward gaze at the golden age of Rublev must pass through the lens of modernist rediscovery, it is now difficult, in retrospect, to think of the Russian icon apart from all its modern couplings. The icon is like painting, folk art, or a masterpiece. But the reverse is also true: painting, photography, film, poetry, prose, or even dream can become like an icon. Forgoing a return to the origin, the authors in this volume instead unravel the manifold operations through which the icon has been reframed and reshaped in the workshops of modernity.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.