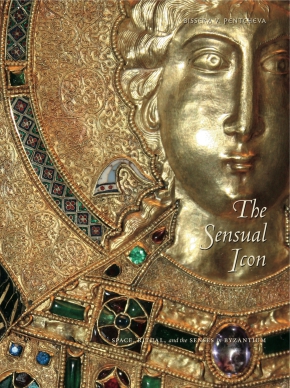

The Sensual Icon

Space, Ritual, and the Senses in Byzantium

Bissera V. Pentcheva

“The Sensual Icon is a major new contribution to Byzantine art history and will be an important turning point in our understanding of the aesthetics and reception of the icon in Byzantium.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

A Web site has been created for this book. To learn more about the work of Bissera Pentcheva, click here: http://www.thesensualicon.com/

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association

By the tenth century, mixed-media relief icons in gold, repoussé, enamel, and filigree offered a new paradigm. The sun’s rays or flickering candlelight, stirred by drafts of air and human breath, animated the rich surfaces of these objects; changing shadows endowed their eyes with life. The Byzantines called this spectacle of polymorphous appearance poikilia, that is, presence effects sensually experienced. These icons enabled viewers in Constantinople to detect animation in phenomenal changes rather than in pictorial or sculptural naturalism. “Liveliness,” as the goal of the Byzantine mixed-media relief icon, thus challenges the Renaissance ideal of “lifelikeness,” which dominated the Western artistic tradition before the arrival of the modern. Through a close examination of works of art and primary texts and language associated with these objects, and through her new photographs and film capturing their changing appearances, Pentcheva uncovers the icons’ power to transform the viewer from observer to participant, communing with the divine.

“The Sensual Icon is a major new contribution to Byzantine art history and will be an important turning point in our understanding of the aesthetics and reception of the icon in Byzantium.”

“The Sensual Icon is a dazzling book, rich in content, brilliant in argumentation, and impressively original. Tracing cross-currents of production, perception, and thinking about the sacred icon within a firm historical context, it proposes a radical reconceptualization of the major form of Byzantine artistic expression.

“A work of flawless scholarship and spirited imagination, The Sensual Icon animates a remarkable artistic legacy and the historical and theological forces that engendered it. Like Hans Belting’s Likeness and Presence, it is destined to guide a whole generation’s view of medieval art.”

“In this, far and away the most ambitious new account of the Byzantine icon, Pentcheva explores the powers and limits of visualization. A book sure to have resonance way beyond its field.”

“Bissera Pentcheva's stimulating The Sensual Icon: Space, Ritual, and the Senses in Byzantium . . . functions on the cutting edge of art historical method, drawing not only on recent trends in the study of visual and material culture but also [on] anthropology and film theory. . . . This is a volume that will transform the discipline of medieval art.”

“Pentcheva’s preferred direction is away from ‘lifelikeness’ towards the ‘living icon’, an image that ‘was literally ‘in-spirited’ (empsychos, empnous, from pneo and pneuma, ‘to breathe and breath’), receiving human breath and responding with a spectacle of shimmer and glimmer’ (p. 122). Her works trace the philosophical and sensual emergence of the living image, the eikon, no longer understood as the flat painted panel of the sixth to ninth centuries, nor only as the metal bas-relief icon that dominated in eleventh-century Constantinople, but rather as the ideas that shaped both.”

Bissera V. Pentcheva is Associate Professor of Art History at Stanford University. She is the author of Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium (Penn State, 2006).

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Imprinted Images: Eulogiai, Magic, and Incense

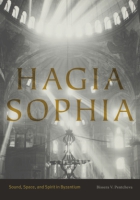

2. Icons of Sound: Hagia Sophia and the Byzantine Choros

3. Eikon and Identity: The Rise of the Relief Icon in Iconophile Thought

4. The Imprint of Life: Enamel in Byzantium

5. Transformative Vision: Allegory, Poikilia, and Pathema

6. The Icon’s Circular Poetics: The Charis of Choros

7. Inspirited Icons, Animated Statues, and Komnenian Iconoclasm

Epilogue: The Future of the Past

Appendix 1: The Icons in the Monastic Inventories of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries

Appendix 2: Byzantine Enamel Icons and the West, Eleventh–Twelfth Centuries

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

The Senses and Synaesthesis

Medieval objects were offered to the senses, their rich surfaces teasing the desire to touch, to smell, to taste, and to experience them in space. Treated as art, displayed in clinical and transparent glass cases, they lose their wider sensorial dimension and submit to our regime of the eye. The textured surfaces, flattened by the even electric lights, deflate to reveal a dead, immobile, taxidermized image.

Focusing on the Byzantine icon, this study plunges into the realm of senses and performative objects. To us, the Greek word for icon, eikon, designates portraits of Christ, Mary, angels, saints, and prophets painted in encaustic or tempera on wooden boards. By contrast, eikon in Byzantium had a wide semantic spectrum ranging from hallowed bodies permeated by the Spirit, such as the stylite saints or the Eucharist, to imprinted images on the surfaces of metal, stone, and earth. Eikon designated matter imbued with divine pneuma, releasing charis, or grace. As matter, this object was meant to be physically experienced. Touch, smell, taste, and sound were part of “seeing” an eikon.

By the ninth century the relief icon, rather than painting, had emerged as the privileged image. It materialized in a rich array of mixed media: metal repoussé figures imprinted on gold and silver, decorated with gemstones and exquisite filigree. These luxury eikones became animated under the agitated light of flickering candles, whose flames were in turn stirred by drafts of air or human breath. Dense layers of fragrance and smoke from burning incense enveloped the icon, while polykandelia (metal disks with multiple oil lamps or candles) and wrought-metal grilles cast lace shadows moving across its face. This luminous, umbral, and olfactory richness was enhanced by the reverberation of music and human prayer. The phenomenal changes affecting and reflected from the icon’s material layers activated the polymorphous appearances of the eikon. In turn, these phenomenal transformations inundated the human senses to the point of saturation, arousing an internal agitation (pathema). Experiencing this pathema, the faithful projected their own psychological stirrings back onto the surfaces of the icon, seeing in the passing phenomenal changes, the shifting shadows and highlights, a manifestation of inner life, of indwelling spirit, transforming the inanimate object into empsychos (animate, inspirited) graphe.

It is the Byzantine relief icon that holds the legacy of tactile visuality, sensually experienced. Because the Eastern Orthodox liturgy maintained its late antique tradition of saturation of the senses, the objects embedded in its rite gave rise to a sensorially rich performance. This synaesthetic experience is characteristic of Byzantium, yet it is rarely discussed in medieval studies. Such links as are made between the senses and the spiritual are often drawn on the basis of the writings of Abbot Suger (b. ca. 1081–d. 1151). Medievalists have tended to characterize Byzantium in terms of strict spirituality, dematerialization, emaciated saintly bodies, and gaunt faces. By contrast, this book uncovers the opposite: the deep sensuality of this Eastern Mediterranean culture, manifested in its palatial and ecclesiastical ceremonies.

My article “The Performative Icon” mapped a new direction of Byzantine studies toward phenomenology and aesthetics. In the display and performance of the Byzantine mixed-media icon, all five senses were engaged, leading to synaesthesis. Viewed in its original setting of shifting daylight and flickering candles and oil lamps, the icon’s surfaces of gold, enamel, and precious stones changed appearance. It is this spectacle that defined the synaesthetic perception of Byzantium, sight experienced also as touch, hearing, smell, and taste.

In both my article and the present study I use “performative” to characterize the spectacle of shifting phenomenal effects on the surfaces of icons and architectural décor, and explore how this spectacle of change in solid, reflective, and umbral contours effects the vividness and vivacity in a subjective but culturally specific vision of paradise. At the same time, I stay close to the original meaning of “performative” as defined by John Austin, who argued for the simultaneity of utterance and action. For instance, when a speaker says “I swear,” he also simultaneously performs a vow. Stanley Tambiah explored “performative” as an anthropologically inflected term pertaining to ritual. He argued that utterances pronounced in the course of a ritual transformed spectators into participants. I apply the linguistic/anthropological definition of “performative” whenever my analysis focuses on the epigrams on icons.

More important, this book uncovers the existence of a Byzantine equivalent of “performative”: the Greek word teleiotes. It derives from the noun teleiosis, which stems from the Eucharist and defines the moment in which the Spirit turns the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. Teleo (the verb) and teleiosis express the process of bringing to completion, to perfection, and to fulfillment, but they also refer to “enchantment,” “initiation in the mysteries,” and the “performance of sacred rites.” Thus the “performative” as a concept in Byzantium is first and foremost a teleiosis, defined by the Eucharist; it is a performance of sacred rituals leading to transformation. Here a metamorphosis takes place under the action of the Spirit, changing the morphe/appearance through contact with the divine, bringing the worldly to completion and perfection, albeit fragile and evanescent. Teleiosis is not just a simple performance, but an entry into mysteries and enchantment. As appearances change, perception transforms. I have coined the term telestike eikon based on what performance meant for the Byzantines. It is a modern term rooted in the Byzantine conceptual and spiritual modeling of the icon after the Eucharistic rite.

Within the sphere of the visual (and here I purposefully use “visual” as opposed to “visible”), “performative” bears the marks of the phenomenal; it refers to the spectacle of changing surfaces under perennially shifting ambient conditions. In focusing on the interaction between object and subject, between icon and viewer, between poetry as seen and poetry as pronounced, I uncover the power of the icon’s spectacle to transform the viewer from observer to participant, communing with the divine.

My interest in the phenomenology of icons was triggered by the experience of these objects at the 2004 exhibition Byzantium: Faith and Power, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There the gilded silver rinceaux of flowers and leaves in the revetments of the large iconostasis icons as well as the delicate enameled cabochons drew my attention to the exuberant materiality of Byzantine metal surfaces. The revetments of these painted icons of the Late Byzantine period evoked the dynamic glitter of the pre-1204 repoussé relief icons. The aesthetic play of visible and invisible was successfully carried from relief to metal-revetted painting. Yet this book focuses only on the Middle Byzantine luxury relief icons.

In the mixed-media icon of the Middle Byzantine period, the face hammered out in gold dazzled with its blinding scintillating glitter, which thus blurred the icon’s visibility and barred access to its form. In a different way, yet similar in its overall aesthetic, the Late Byzantine painted icon covered in metal revetments denied full access to the eye (fig. 1). The figure and face of the saint were submerged in darkness, an absence, an abyss of blackness, opening before the shimmering glitter of twisted gilded silver rinceaux. Rather than an imprint of absent form, the painted icon became the chasm of darkness surrounded by a halo of lustrous metal.

The revetted icons from the Peribleptos church in Ohrid brought to the Metropolitan Museum in 2004 became the inspiration for my research in phenomenology of Byzantine art. I started this project by focusing on poetic inscriptions, which led me to the Middle Byzantine luxury icons, the subject of the current book. My interest is not exceptional, however, for scholarship on Western medieval art has also recently shown an interest in materiality, a direction well exemplified by the work of Herbert Kessler, Jean-Claude Bonne, and Brigitte Buettner.

A relief icon of the Theotokos in Treviso exerted an even more profound impact on my thinking. I owe thanks to Claudio Rorato and the nuns of the Monastero della Visitazione, who showed me their Madonna: a wooden relief icon covered in gilded revetments. I arrived at the monastery one gray December morning. My innocuous request that we switch off the electric lights and instead bring candles opened a gateway to a Byzantine teleiosis: a completion, perfection, mystery. We moved this flickering candle up and down, left and right, across the surface of the relief icon. In response, the shadows cast over the eyes of the Mother of God changed, manifesting a sense of animation, miraculously imbuing her face with liveliness. Mary’s moving gaze set a current through my body. For the first time, I experienced what we easily call “object” as living and present. It is to this liveliness and vividness created through phenomenal effects that I now turn in the pages of this book, intending to explore how the icon’s performance unfolded in space.

The Performative Paradigm: Hierotopy

The Byzantine icon has been a subject of study mostly with respect to its style, iconography, and liturgical function, and even then the emphasis has always rested on the painted icon. By contrast, this book uncovers the forgotten life of the relief icon and explores its sensual presence. The chronological frame begins with the cults of the column saints, the stylites, of the fifth and sixth centuries and culminates in the twelfth century, before the Crusader capture of Constantinople in 1204. The focus lies on the interaction that takes place in the physical space between viewer and object.

My study explores its subject from the position of the aristocratic patron who commissioned and witnessed the sensual spectacle of the Byzantine metal relief icon. It is this Constantinopolitan aristocracy of the Middle Byzantine period that stands behind my generic terms “spectator,” “viewer,” and “faithful.”

In Byzantine visuality, which was defined by the theory of extramission, the eye was active, sending off rays that touched the surfaces of objects. The viewer’s gaze sought the tactility of the icon’s textures. At the same time, the radiance reflected from the gilded surfaces rendered perceptible the rays that the “animated” image itself sent off to touch and in a sense capture the viewer. The space between icon and beholder was activated by the exchange of the gaze.

Otto Demus most prominently brought up the subject of interaction between image and viewer in his Byzantine Mosaic Decoration, of 1948. He discussed monumental mosaics as “space icons.” According to him, these images reconstituted themselves before the gaze of the beholder. The mosaics were not static compositions; the changing atmosphere in the church, the shifts in the intensity of light and clarity of air, and movement and distance from the images affected the way the scenes appeared to the viewer. Often the action was completed within the actual physical space of the mosaics themselves. For instance, the exchange of greeting between the archangel and the Virgin in the scene of the Annunciation at Daphni takes place in the void before the squinch (fig. 2). The two figures inhabit its corners, while their exchange traverses the air in between. The Byzantine “picture space” thus opened in front of the image rather than behind it. In contrast to the familiar Renaissance model of painting as a window opening onto a vista, the Byzantine spatial icon sought to invade the physical space in front of it; its figures, pressed to the very surface in their static poses and fixed gazes, could unfold their stories only in the space of the beholder.

My book explores the same interaction but anchors the discourse on the luxury mixed-media eikon. Its excessive materiality addresses itself to the hands and mouth of the supplicant. The two Byzantine terms used to define the interaction of the faithful with the image are aspasmos (kiss) and proskynesis (pros-, “toward,” -kyneo, “kiss,” encapsulating the acts of prostration and kiss); both indicate a body-centered ritual. The proskynesis, which disrupted the air through human movement and breath, set off the optical dazzle (photismos) of the icon; the photismos also grew through the lighting of candles and oil lamps before the image. The shimmering, glittering effect of light reflected from the metal surface, increased also by the breathing and movement of the faithful before the panel, gave rise to a sense of animation of the image. The body of the faithful was thus fully engaged in the spectacle of the icon’s performance. Similarly, according to the Greek aspasmos, the faithful “touched the icon with eyes and lips.”

Anthony Cutler has drawn scholarly attention to this tactility of vision in his discussion of Byzantine ivories. The surface of these icons shows signs of rubbing at places where Byzantine hands and lips would have touched the plaque in devotion. Tactile visuality may also account for the prevalence of relief icons among the surviving objects produced in Byzantium after Iconoclasm; their number far exceeded that of panel paintings. The textured surface of repoussé silver gilt, or ivory, and steatite appeals to the “touch of the eyes and lips.” Even encaustic offers more relief than the layering of tempera on a painted wooden panel. The encaustic image is created by pushing the soft surface of wax with a palette knife, compressing and elevating, and thus molding a relief texture. This book emphasizes the predominance of relief icons and further explores the significance of the surface of these objects of devotion.

Tactility and the disruption of visibility (the rendering of images indecipherable in the dazzle of gold) are essential aesthetic principles of the Byzantine display of the Holy. While the haptic aspect dominated both Byzantine and Western medieval art of the early period, a change gradually spread in the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, separating the two cultures. Western visuality eventually shifted to intromission. In this theoretical model it was the object that sent out rays, which in turn penetrated the membranes of the eye. The external information received was soon processed, categorized, stored, and internalized in the five chambers of the brain. Intromission placed new demands on the image; rather than a tactile surface and an object comprehended only in its relation to and interaction with the viewer, the Gothic image became self-sufficient, an optical, illusionistic likeness. Visibility became a necessity; relics previously hidden behind metal sheaths and opaque gemstones now were displayed in glass and crystal containers. The sacred was visually available. By contrast, the Byzantine image retreated further into the tactile invisibility of the sacred (a surface that could be touched and sensually experienced, yet an image/face drowned in the dazzle of gold) (fig. 1). The painted surfaces of Late Byzantine icons were hidden in the shadow of the raised and glittering metal revetments and the silk covers enveloping the image.

Byzantine tactile visuality rested on an aesthetic of exuberant surfaces. These present a taste for sensual pleasure stimulated by an abundance of textures, glittering light effects, the sweetness of honey and incense, and sound. Yet Byzantium does not appear in the discussion of sensual pleasure in medieval studies. Not surprising, this omission has provoked the following comment from Cutler:

Delight in the polychrome incandescence of gemstones, in the affective power of the precious metals, is an aesthetic perfectly understood by scholars when they read Suger of St. Denis, but too little considered when they contemplate Byzantine commissions. Objects like the gem-encrusted, gold, and enamel lectionary cover in the treasury of the Lavra monastery on Mount Athos, embody that photismos, the spiritual illumination that was a perennial Christian obsession.

It was the sensual splendor of Byzantium that seduced the envoys of Vladimir of Kiev into accepting the Eastern Orthodox faith when in 988 they experienced the liturgy in Hagia Sophia: “We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty and we are at a loss how to describe it. We only know that God dwells there among men.”

Sensory experience has only recently become the subject of scholarly exploration. Liz James introduced it in her seminal book Light and Colour in Byzantine Art (1996), which explores the perception of color in Byzantium and argues that the Byzantines valued the optical effect of brightness and saturation over hue. James’s more recent article “Sense and Sensibility in Byzantium,” on the corporeal experience of the space in Hagia Sophia, continues this topic.

Similarly, Rico Franses’ “When All That Is Gold Does Not Glitter,” a study on the perception of gold in Byzantine mosaic and miniatures, draws attention to the performative aspect of Byzantine art. The objects of Franses’ study have light-reflecting elements (gold backgrounds and chrysography in the depiction of highlights) and light-absorbing ones (colored stone tesserae and paint). This binary creates a dynamic, polymorphous meaning, which issues from the figure’s shifting visibility, caused by the glittering effect of gold. The perception of hue is overwhelmed by the optical dazzle of the gold. As Franses writes:

In comparison with Renaissance paintings, then, which constantly require high levels of light to be fully appreciated, and simply fade into the darkness without any further ado when those levels drop, these [the Byzantine] are the most flexible of images. They are not simply polysemic, . . . but polymorphously polysemic, entirely changing their appearance and meaning in response to ambient light conditions. They are, to this observer, the most subtle art and the most theologically complex pictures because they do not simply represent theology, but enact it.

Glenn Peers too has focused on the role of light in evoking divine presence in the man-made icon. He explores the twelfth-century painted and metal-revetted panels of the Annunciation at Ohrid, discussing them as Gesamtkunstwerken. His analysis of the Mandylion of Genoa also draws attention to the sacred as signified through the dazzle of the metal revetment when juxtaposed to the darkness of the painted holy face at the center. Elsewhere Herbert Kessler has explained the Mandylion face submerged in darkness as an expression of the negative theology of Pseudo-Dionysios. Having registered the absence of light as the invisibility of God’s face, the eye defined this shadow as an anticipation of what the pious would see at the end of time.

Alexei Lidov’s volume on hierotopy marked new ground in Byzantine studies. His concept (from hiero-, “sacred,” and -topos, “space”) concerns the spatial dynamics of sacred ritual unfolding in urban scapes, architectural interiors, icons, liturgical objects, and miniatures. Hierotopy is a collection of essays by different authors. Lidov wrote the introduction and an article on the Hodegetria. He insisted on the existence of “image paradigms”: culturally specific systems that enabled the structuring of space to stir the subjective experience of the divine. “Hierotopy” is defined as human creativity, like that of film production, engaged with the structuring of a performance unfolding in a vast temporal and spatial framework. As such, hierotopy touches upon multisensory experience and materiality functioning under changing ambient conditions. Performance is thus crucial to hierotopy, for the “image paradigms” reveal themselves in the moments of action, of restructuring two-dimensionality into three-dimensionality. Lidov also mentions the interaction between object and viewer, and the activation of the space between them, concepts that recall those Demus derived when studying Byzantine mosaics. He also suggests the reading of spatial experience in preface miniatures such as those of the James Kokkinobaphos manuscript (Vat. Gr. 1162, fol. 2).

Earlier on, I had developed the same idea in my analysis of the preface illumination of the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzos (Sinai, Cod. Gr. 339, fol. 4v), where I argued that the formal structure of the miniature functioned as a visual ekphrasis. The cubist arrangement of architectural forms enabled simultaneous interior-exterior views, the encounter with dome and sanctuary, thus simulating the experience of a corporeal movement through space. More recently, Robert Nelson has written about a similar spatial dynamic, an unfolding ritual encoded in the miniatures of an eleventh-century lectionary (Florence, Laurenziana Med. Palat., Cod. Gr. 244).

Nicoletta Isar has offered a potent new approach to architectural space and spiritual experience by identifying and exploring the concepts of chora (space in a flux of becoming) and choros (circular, revolving movement/dance). Focusing on the sixth-century ekphraseis of Hagia Sophia by Prokopios and Paul the Silentiary, Isar argues for the dominant use of the terms chora, choreuo, and choros in the construction of the notion of expanding, moving space: the space of liturgical action, of the Eucharist. Chora is a space of contraction and expansion; choros, enacted by people and light, is captured in the circular plans of ambo and ciborium, in the circular disks of light, and finally in the priestly circumambulation of the altar. Through this layering of circuits, the dance of the human and material simultaneously withdraws and advances in order to make space for divine energy to become perceptible, offering a space for participation and fusion with the divine. I have taken Isar’s idea further in identifying chora in the Byzantine icon, exploring the spatial dynamics of the eikon, and defining its circular choros as a site of participation in the divine. Chora/choros is thus intertwined with the concept of grace/charis, the circle being the performative paradigm of charis, a circuit of human participation in the divine.

The Medium of Icons: Painting Versus Relief

Medium—relief, enamel, metal, painting—and the perceptual experience of it form the two major themes in this book. The sensual splendor of the Constantinopolitan eikon depended on and stemmed from the opulent display of variegated surfaces, of materials skillfully shaped, metamorphosing under the influence of changing light and air. In recent decades studies on Byzantine icons have never seriously raised the question of medium. Traditionally, the word eikon has been identified with painting in tempera or encaustic on wooden boards. But this begs the question whether painting was the dominant form in Constantinople and, even if it was, whether the icon medium was site specific, that is, dependent on the location of the city. Did the icon of Constantinople differ from the one in Rome or at Sinai? This book offers an unexpected answer.

Robin Cormack introduced the contextual approach to icons, discussing their production and perception through the record of saints’ lives. He reconstructed a vision of Byzantine society based on its icons. Nancy Ševčenko’s work on the so-called decorated icons has also sharpened my interest. Relying on the cataloguing of objects in monastic typika, she has identified kekosmemene as painted panels covered with bejeweled silver-gilt revetments. The identification of the eikon with the painted image has continued in recent studies on the icon published in the collections edited by Maria Vassilaki and by Liz James and Antony Eastmond. At the same time, these publications have introduced new theoretical and technical approaches.

From A. W. Carr’s vast oeuvre on Byzantine icons and Marian devotion in Constantinople, Cyprus, and Sinai, I shall only draw attention to two seminal articles: one on Komnenian Iconoclasm, the affair of Leo of Chalcedon (1082–95), and the second on the way the charismatic Marian icons presented the divine through the visual rather than the textual. In both studies, Carr opens the discourse on the materiality of icons, redirecting attention back to the figure of the Mother of God and reading the visual field as a Marian body:

Our approach to icons hitherto has been very logocentric. It has been so visually: we have focused on the Child. And it has been so theoretically: we have focused on linguistic theory. I wonder if this is a valid approach to an image like this [icon of the Mother of God holding and presenting the infant, who has assumed a twisted body posture that proleptically evokes his Passion]: if the strong fleshy Christ does not bring with it a stronger focus upon his Mother and with this a performance that is neither acoustic, as it was for Nelson, nor transubstantial, as it was for Vikan [who viewed the icon as Eucharistic bread], but presentational: a quiet offering of what can only be seen. This is not to say that the icons of the Kykkos type represent the Presentation but rather that presentation is as basic a matrix for them as speaking is for images of the Pantokrator.

Carr’s approach stands in contrast to the standard logos-centered treatment of the subject, where the icon is reduced through the semiotic lens to the word: the icon as an open book one reads, as a pictorialization of voice. Carr argues for the need to shift the emphasis in scholarly discourse on Byzantine icon theory from the word to the body: a shift from dominance of Christ’s image to that of the Mother of God.

Carr concludes that as a result of associating the iconic with Mary’s body, sight becomes dominant, tying the icon to an emerging pictorial naturalism. Hans Belting has offered this interpretation in his fundamental book Likeness and Presence. He argues that a naturalist style of painting developed in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, pictorially engaging the icon with poetry, rhetoric, and new pietistic trends in monasticism. Belting identifies the Greek term empsychos graphe, “animated painting,” with naturalism and argues for the cultural perception of this style by twelfth-century contemporaries as “new” (kainourgos). He thus saw a shift from the perception of the icon as divine presence to that of the icon as art.

Henry Maguire has independently shown how the tradition of depicting the Crucifixion, as recorded in painted icons and frescoes, bore this marked shift from awesome truths to human suffering, thus inaugurating a move toward naturalism.

Some have challenged Belting’s interpretation about the rise of pictorial lifelikeness. Yet these critiques never challenged the dominance of painting. My own question with regard to kainourgos concerns medium. To date, we have tended to identify the Constantinopolitan icon production mostly with painting. Belting’s “new style” empsychos graphe rests on the evidence of the painted icons of Sinai. This study, on the other hand, demonstrates that Constantinople (of the ninth–twelfth centuries) was not tied to a hierarchy that privileged painting. Instead, it identified with the luxury mixed-media icon.

The relief icon made of metal acquired a privileged status in Byzantium after Iconoclasm (730–843). This move away from painting and toward relief was signaled in the Iconophile treatises of the early ninth century. The writings of Theodore Stoudites in particular defined the icon as an imprint (typos) of likeness (homoiosis) on a material surface. This mechanical reproduction of an intaglio secured the correct and inalterable transmission of homoioma. And since likeness was the true link, binding icon to prototype, its preservation ensured the legitimacy of the man-made image.

The importance of the relief icon has escaped notice in modern scholarship because the painted image is the dominant example in the two extant collections in Rome and Sinai. On the heels of the Getty Center’s 2006–7 exhibition “Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai,” it is necessary to raise the question, How has Sinai changed our perception of the Byzantine icon? All of its collection consists of icons painted on wooden panels in tempera or encaustic. Ranging from the sixth to the twentieth centuries, these offer an unprecedented opportunity to study the history of the medieval pictorial tradition. Yet at the same time, they have seduced scholars into equating the Sinai painted panel with the normative Byzantine icon. Few scholars have raised their voices against this treatment of the Sinai collection as characteristic of the lost Constantinopolitan icon production. Kurt Weitzmann, however, expressed this concern in his book The Icon, in 1978:

A history of the icon from the sixth through the ninth centuries according to style and content cannot yet be written because of the extreme scarcity of the material, which has been preserved almost exclusively at Mount Sinai, where it escaped the destruction of the Iconoclasts. Even where the tenth century is concerned, the history of the painted icon is still an enigma, since only a handful of examples have come to light, once more at Mount Sinai, although a substantial number are preserved in other media such as ivory. A coherent picture of icon painting begins to emerge only with the eleventh and twelfth centuries. But from this period as well, the majority of extant icons are in the possession of Saint Catherine’s Monastery, and this easily explains why our study relies heavily on this unique collection. Only from the thirteenth century onwards are a very considerable number of icons known from various parts of the Orthodox world—Greece, other Balkan countries, and Russia.

Throughout this passage, the Sinai collection takes center stage in exemplifying the history of the icon. With objects from the sixth through the twelfth centuries, the Sinai wealth rules indomitable over a landscape of loss. No other collection can match the number and diversity of paintings kept at St. Catherine’s. And the Sinai painted icon has thus emerged as the norm.

Yet was this really the case with the icon tradition in Constantinople before the thirteenth century? Was panel painting the dominant form there as well? Only Weitzmann, acting upon his earlier research and publications of Byzantine ivory plaques, suggested the possibility that the painted icon might not have been the norm in the Byzantine capital in the ninth and tenth centuries. In fact, the relief icon in metal, enamel, and ivory appears to have occupied a higher place in the Byzantine aesthetic hierarchy. Weitzmann wrote: “That there remain so very few painted icons from this period [in Constantinople] may be due less to a large-scale destruction than to the fact that icon production was, to a larger extent than we today realize, entrusted not to painters, but to carvers of marble, stone, and ivory, as well as to workers in metal and enamel.” I only discovered Weitzmann’s words after I had, in 2006, published my own hypothesis about the prominence of the relief icon in Constantinople and made a trip to the Republic of Georgia, where I saw the rich medieval collection of metal relief icons. There I encountered for the first time the staggering, almost life-size format of some of these objects.

The metal icons of Georgia form a significant group that has never been carefully explored in Western scholarship. Giorgi Chubinashvili published a large corpus in Russian in 1959. In it he assembled all extant pieces kept in the storage spaces of Tbilisi museums. Through analysis of form and style he dated the icons, arranged them into centuries, and transcribed and translated into modern Georgian and Russian some of the donors’ inscriptions. This monumental work has rarely been taken into consideration in subsequent scholarship in the West, not surprisingly due to the difficulty of mastering Russian and Georgian. Yet these two volumes are crucial for any exploration of image theory or sculpture in not just Eastern art but medieval art in general. Moreover, Georgia is unique as a place of continual new discoveries of medieval art. The relative remoteness of the country and of the mountainous region of Svaneti, where many of the relief icons dwell, as well as the long isolation of the Communist period, has delayed study of the icons. The metal panels of Georgia may constitute the fastest growing field of Eastern medieval art in the next decades; yet they demand from scholars expertise in Russian and Georgian (the latter both medieval and modern). This field is open for a future generation of scholars.

Hans Belting in his otherwise encyclopedic Likeness and Presence never considers the significant corpus of medieval Georgian metal icons. Therefore, he ends up with a history of the painted icon. His book has become the norm for any subsequent study of the icon, but it is a norm constructed on incomplete evidence. The necessary corrective is to introduce and explore the relief icon in the East.

Changing Appearances: The Byzantine Concept of Animation

By exploring the aesthetic hierarchy of media and uncovering the rising importance of bas-relief in Byzantium, this study will uncover how medieval lifelikeness and animation were expressed through performance of shifting appearances rather than pictorial or sculptural naturalism. We have inherited an art history shaped by the Renaissance and in particular by figures such as Alberti, who secured the dominance of painting with these words:

The virtues of painting, therefore, are that its masters see their works admired and feel themselves to be almost like the Creator. Is it not true that painting is the mistress of all the arts or their principal ornament? If I am not mistaken, the architect took from the painter architraves, capitals, bases, columns and pediments, and all the other fine features of buildings. The stonemason, the sculptor, and all the workshops and crafts of artificers are guided by the rule and art of the painter. Indeed, hardly any art, except the very meanest, can be found that does not somehow pertain to painting. So I would venture to assert that whatever beauty there is in things has been derived from painting.

According to Alberti, painting interpenetrates and binds together all other forms of art. It exceeds these crafts and becomes high art. This perception of painting as the queen of all the arts has a continuous strong hold on our imagination, to the extent that we are still predisposed to equate the Byzantine icon with tempera or encaustic painting on wooden panels. We have retrojected a false dominance of the painted image over the relief icon in the earlier periods and thus fabricated a memory of the past that fits better in our post-Albertian aesthetic system wherein painting is seen as the privileged medium.

For Alberti, the value of painting stemmed from its veracity. It showed objects on a flat surface while preserving through perspective and chiaroscuro an impression of three-dimensionality and substance. Because it achieved such a high level of illusion through superior human skill, painting became the queen of all the arts. As a Byzantinist, I would not explore the reception of Alberti’s text or the multiplicity of views regarding depiction or the comparative merits of painting versus sculpture discussed in the paragone of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Suffice it to acknowledge that Alberti defended a position that eventually became dominant, and it catapulted painting to the pinnacle of high art.

When medieval, and especially Byzantine, art is put on the Procrustean bed of Alberti’s Pictura, it is found lacking; for it is not concerned with conveying an illusion of three-dimensionality and depth. Alberti’s privileging of painting has also led Byzantinists to dwell more on miniatures and panel-painted icons than on bas-relief and enamel. Yet is the Albertian lens suited for the Byzantine material?

In privileging painting, the Albertian aesthetic has taxidermized and immobilized the image, whose lifelikeness depends on the artist’s skill in pictorial naturalism, creating a picture fully available for view and examination. By contrast, the Byzantine aesthetic promoted the unstable, ever-changing appearance of an object, its variegated surfaces phenomenally affected by the shifts in ambient light, air movement, sound, and smell. The object lived, transforming in a changing space, veiling and unveiling its uncontainable materialities. In this aesthetic, multimedia icons anticipated, already in their production, the spectacle of animation achieved through physical light and shadow.

The unchangeability of the divine shape was paradoxically juxtaposed to the mutability of the material surface. Sight was thus polymorphous: an exchange and interaction of fiery rays on matter, changing the appearance of objects. In elevating the metal eikon as the ideal image, Byzantium simultaneously promoted the ancient concept of charis/grace as glittering metal. The luxury mixed-media eikones of Constantinople disassociated the image, and image-making, from the goals of pictorial naturalism. These relief icons offered a spectacle of charis: of the dance of shimmering glimmer. The object thus acquired presence and animation through movement and change reflecting the phenomenal shifts: tremulous shadows, flickering lights, wafts of smoke and fragrance. Zographia after Byzantine Iconoclasm changed from “painting from life” to “material imprint/seal imbued with Spirit”—empsychos graphe.

Etymology: Graeca sunt Verba

Begriffsgeschichte defines my methodology. I am interested in the spectrum of meanings of words and in how these different levels resonate once a word is put in context, how its colors/meanings fluctuate when subjected to the close proximity of other logoi. It is these layers of meaning of words that my analysis and translation put to the fore. As part of this deep engagement with etymology and semantics of words, I have been able to show how charakter and typos were a pair of opposites. Charakter designated the intaglio, capturing the “snow angel” left in matter by the departing divinity; or better, understood in magic terms, charakter was the embodiment of a spirit in a material substance. By contrast, typos was the imprint of charakter on matter.

My translation also challenges the meaning of enkaustes. Rather than read it according to tradition as “encaustic” wax painting, I have shown how the word in the inventory lists of monastic foundation documents is often used together with “gold” and “silver.” Enkaustes thus refers not to the melting of wax but to the warming of precious metals before they are hammered out. As such, the term identifies the metal repoussé eikones.

Similarly, the words the Byzantines used to designate enamel—cheumeuton, cheimeuton, elektrinon, and hyalon—show a particular cultural perception of this medium. Some of these terms capture the sheen of translucent ice; others refer to the mixture of metal alloys with gold; still others draw on the visual similarity between the radiance of glass and the brightness of translucent emerald. As such, the Byzantine vocabulary builds a perception of enamel as radiance and light; this conceptualization resonates with the Islamic mina, which refers to paradise, the celestial, and emerald. Yet both the Byzantine and Islamic terms are diametrically opposed to the Western term smalto, concerned only with the melting of metal alloys.

Using Begriffsgechichte, this study uncovers the meaning of empsychos graphe as animation, inspiritment; the Greek term captures the process by which pneuma/breath is imparted to matter. Through this process of empsychosis the faithful experiences the object, and the space in which it is set, as alive. I tend to use the English word “present” to define an object experienced by the faithful as living and breathing. At the same time, this very process of animation is deeply subjective, issuing from the interaction of viewer with matter in changing ambient conditions.

Translations are not transparent texts, even when done by philologists. As an art historian I bring a different sensitivity to these written sources. While there are shortcomings in my nonphilologist approach to the Greek texts, I have risked those in order to show the potential meaning of these passages as seen through the eyes of an art historian. All the existing translations have started from the point of view that eikon means “painting”; this is a worldview that colors the perception of the current literature. By contrast, guided by the understanding of eikon as a word encompassing the Eucharist, saintly bodies, and bas-relief, this project has tapped into the Greek sources and uncovered the shift from the pre-Iconoclast eikon as a magic site of the chiastic entwining of Spirit and matter to the post-Iconoclast icon as typos: an imprinted form on matter lacking pneuma but set up to receive and respond to human breath emptied out as prayer. I have started this process of rereading, inviting the philologists to join in and see with new eyes—the eyes of an art historian—so that we may collectively change the motto for the future generation of scholars from graeca sunt non leguntur to graeca sunt, translate!

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.