Walter Pach (1883–1958)

The Armory Show and the Untold Story of Modern Art in America

Laurette E. McCarthy

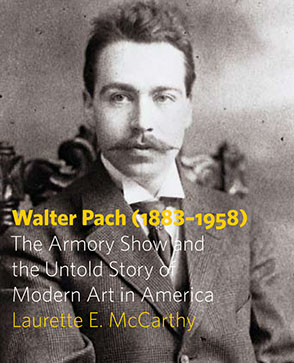

Walter Pach (1883–1958)

The Armory Show and the Untold Story of Modern Art in America

Laurette E. McCarthy

“Laurette McCarthy, a specialist in early twentieth-century American art and its European background, has produced a detailed study of one of the neglected figures of the period—Walter Pach. Pach was a brilliant mirror of the age, an influential critic, essayist, historian, lecturer, dealer, agent, and, not least of all, painter. McCarthy has dealt convincingly with all these facets, drawing on a good deal of unpublished documentation that has never before been tapped. Her book is a compelling biography that deals not only with the facts of Pach’s life but also with his engagement with the aesthetic and social themes of his time.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund

“Laurette McCarthy, a specialist in early twentieth-century American art and its European background, has produced a detailed study of one of the neglected figures of the period—Walter Pach. Pach was a brilliant mirror of the age, an influential critic, essayist, historian, lecturer, dealer, agent, and, not least of all, painter. McCarthy has dealt convincingly with all these facets, drawing on a good deal of unpublished documentation that has never before been tapped. Her book is a compelling biography that deals not only with the facts of Pach’s life but also with his engagement with the aesthetic and social themes of his time.”

“Drawing on a wealth of primary sources, Laurette E. McCarthy’s meticulously documented biography of Walter Pach is an important contribution to the history of American modernism.”

“This book fills one of the most gaping lacunae in the literature on modern art, for it provides a vivid, enlivened, and accurate portrait of one of the most influential yet overlooked figures in the history of American art. Through his writings, lectures, and relentless efforts to educate, for nearly a half century Walter Pach worked tirelessly behind the scenes to introduce modern European art to an essentially unaware and uninformed American public. It is safe to say that without his promotional efforts—particularly as they pertain to the organization and staging of the celebrated Armory Show of 1913—the development of modern art in America might well have taken a very different course, one far less exciting and intellectually stimulating. Today, artists, critics, curators, and historians—indeed, anyone involved in the field of modern and contemporary art—are in one way or another indebted to the path he charted for us, and specifically to the decisions that shaped our aesthetic future and contributed significantly to the advancement and understanding of modern art in America.”

“No student of modern art should miss this thorough and fascinating study of one of the most important figures of the time, still little known except to specialists.”

“This is the 1st full length monograph about Walter Pach, a very important person in the development and promotion of modern art in America. Most of those interested in art know of the ‘Armory Show’, the 1913 exhibit in an armory in New York City, actually entitled ‘International Exhibition of Modern Art’. Many do not know that the importance of the show was the international aspect and that the only way this happened at all was because of Walter Pach. . . .A good read, using material from archival sources, with many illustrations, this book should be of interest to those who wonder how the European artists got their start in America.”

Laurette E. McCarthy is an independent scholar and curator.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

Acknowledgments

1. Family Background and Influence

2. Art Student Days

3. The Formative Years

4. The Armory Show

5. Pach the Artist, 1903–1919

6. Modern Art Exhibition Organizer

7. Society of Independent Artists

8. Liaison, Agent, Dealer, and Advisor

9. Writings on Modern European and American Art

10. Lectures on Modern European and American Art

11. Latin American Art and Artists

12. Historian

13. Return to Naturalism, 1919–1958

14. Final Decade

Epilogue

Appendix: Chronology

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Walter Pach (1883–1958) was one of the most intriguing and influential figures in the history of twentieth-century art and culture, yet very little has been written about him and much of it is incorrect. He had the uncanny ability, and good fortune, to be at the right place at crucial moments in the history of art and he seized the opportunities presented to him to have a profound effect on modern art in the United States, Europe, and Mexico.

Born and raised in Manhattan, Pach was first exposed to art through his father, Gotthelf, an owner of Pach Brothers Studio, one of the most prestigious photography firms in the United States. The studio captured the images of the prominent social, theatrical, and political figures of the day and was the semiofficial photographer for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While his father photographed the collections in the museum, Pach marveled at the art on view. This youthful experience, as well as other encounters with art at antique shops on the city’s Lower East Side, profoundly influenced Pach’s decision to become an artist and critic.

Between 1903 and 1913, Pach was a young man of two worlds: New York City and Europe. Although he lived with his parents in Manhattan most of these years, he spent many of the summer months between 1903 and 1910 in Europe, as a student and as an agent for William Merritt Chase’s and Robert Henri’s summer sessions abroad. In addition, he lived in Paris from the fall of 1907 until July 1908, from September 1910 through June 1912, and from August 1912 until January 1913. While living in Paris, Pach became a true insider in the contemporary art scene and developed close friendships with the most vanguard artists, writers, and thinkers of his time, including Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Marcel Duchamp, Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Constantin Brancusi, Alexander Mercereau, Jo Davidson, Patrick Henry Bruce, and others. These relationships were vital for the development of Pach’s art and aesthetics. He also came to know many of the prominent collectors in Paris, including the Stein families, and he was on first-name basis with the leading contemporary art dealers, among them Ambroise Vollard, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Joseph Brummer, Eugène Druet, Stéphan Bourgeois, and Felix Fénéon of Galeries Bernheim Jeune. These connections helped shape Pach’s multiple careers as an organizer of exhibitions, a liaison between European artists and dealers and American galleries and collectors, and a critic.

These contacts proved invaluable when Arthur B. Davies and Walt Kuhn came to Paris in the fall of 1912 to select works for the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show. Pach served as the European agent for the show and was instrumental in securing the loan of paintings, sculptures, and prints from European—particularly Parisian—artists, collectors, and dealers. Without him the exhibition would have been a completely different event. It was Pach, after all, who selected Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 for inclusion in the Armory Show, a decision that helped change the course of modern art in the United States. He was the only individual present at the exhibition every day and at each of its three venues; in this way he had a profound impact on visitors to the show. He became, in effect, the voice and the face of modern art for many Americans. As a publicist, chief salesperson, and lecturer during the exhibition’s run, Pach helped promote and disseminate to a large audience the ideas behind the modern art on view.

From the 1910s through the 1940s, Pach continued in his role as champion of modern art—European, American, and Mexican. In October 1914, after war broke out on the continent, Pach risked life and limb to travel to Paris to secure loans from European artists for exhibitions back in New York. He was the European representative for the Montross, Carroll, and Bourgeois galleries in Manhattan throughout World War I, serving as intermediary between them and such artists as Matisse, André Derain, Odilon Redon, Raoul Dufy, and the Duchamp brothers. Pach helped organize numerous groundbreaking exhibitions in the United States, including the first large-scale shows of works by Paul Cézanne and Matisse. He was, in fact, Matisse’s first agent in the United States, until 1924, when Matisse’s son Pierre arrived in Manhattan and was met at the dock by Pach. Besides supporting foreign art, Pach encouraged the New York galleries to promote the work of contemporary Americans such as Maurice Prendergast, Morton L. Schamberg, and Joseph Stella. He was an advisor to the prominent art collectors John Quinn and Walter Arensberg, helping them amass two of the earliest and most significant collections of modern art in the United States and introducing them to French artists—Duchamp, Gleizes, Francis Picabia, and Jean Crotti—who resided in Manhattan during World War I. In 1917, Pach helped found the Society of Independent Artists in New York and in 1923 organized the first exhibition of contemporary Mexican art in the United States, showing works by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros, among others.

In addition to his roles as an agent and liaison, Pach devoted a substantial amount of his career to his work as a critic, and his importance in this arena lies in the credibility with which his opinions were met and the diversity of forums in which he presented them. His vast knowledge of art history, his understanding of the theories of art upon which works by the fauves, cubists, and futurists, among others, were based, and his personal relationships with the most advanced artists and thinkers of his day made him the perfect candidate to promote transnational modernism in the United States. Pach appealed to a broad a sector of the public through presenting his ideas in popular magazines, newspapers, and specialized journals in the United States, France, and Mexico; he published in Scribner’s Magazine, the Century, the New York Times, the Dial, the Freeman, the Nation, the New Republic, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, L’Art et les Artistes, L’ Amour de l’Art, México Moderno, Cuadernos Americanos, and Letras de Mexico. His books include Georges Seurat (1923); The Masters of Modern Art (1924); Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Sculpteur, 1876–1918 (1924); Ananias, or the False Artist (1928); Vincent van Gogh, 1853–1890: A Study of the Artist and His Work in Relation to His Times (1936); Queer Thing, Painting: Forty Years in the World of Art (1938); Ingres (1940); The Art Museum in America (1948); and The Classical Tradition in Modern Art, published posthumously in 1959. Pach was the first to translate Eugène Delacroix’s Journal into English, and he translated noted French art historian Élie Faure’s five-volume work, History of Art (1921–1930). Through his literary work, Pach became friends with many of the leading lights in the literary and intellectual worlds of New York and Paris, including Wallace Stevens, Van Wyck Brooks, Lewis Mumford, and Alexandre Mercereau.

The history of modern art and art criticism would have been quite different without the work of Walter Pach. He not only championed the art of his own time, but also had a comprehensive knowledge of art history. In his books and articles he discussed a wide range of subjects, from ancient Mexican and Native American art to early twentieth-century modernism. His views were not radical; however, they were perceived to be authoritative and reached a wide audience at home and abroad. His writings on modern, especially French, art were instrumental in winning its acceptance in the United States. In recognition of his enduring, and at times heroic, efforts on behalf of French art and artists, he was awarded the medal of the Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur in 1950.

Between 1907 and the 1940s, Pach lectured extensively on art in the United States and abroad. In 1918, he taught the first course on modern art at the University of California, Berkeley. During the summer of 1922, he lectured at the Universidad Nacional in Mexico City, where he met Rivera and Orozco. He later returned to Mexico City, again teaching at the university as well as at San Carlos Academy from July 1942 through July 1943. He conducted a course on modern French art for New York University students at the Louvre in the summer of 1926. In addition, he taught numerous art history classes at Bowdoin College in Maine and, in New York, at the Art Students League, Columbia University, New York University, and City College of New York (his alma mater). He was the first instructor of painting at Columbia Teacher’s College, Columbia University, in 1936–37. At the height of his influence—from the mid-1920s to the early 1940s—Pach crisscrossed the country, lecturing at most of the major U.S. museums, libraries, art galleries, and art institutions. During this crucial period in the history of modern art, Walter Pach was more of a household name across the United States than was Alfred Stieglitz.

Pach’s support of contemporary painters and sculptors did not change dramatically during his later decades. He continued to admire the paintings and sculptures of American colleagues such as Maurice and Charles Prendergast, William Glackens, John Sloan, John Flannagan, and Arthur B. Davies, and in various articles, and through the annual Society of Independent Artists’ exhibitions, he promoted their art. He also wrote essays on his favorite European and Mexican artists, including Picasso, Brancusi, the Duchamp brothers, Georges Rouault, Jacques Lipchitz, Rivera, and Frida Kahlo. He highly valued the contributions to contemporary art made by these artists; however, he could not accept the vanguard works of the abstract expressionists, viewing their paintings as “the hollowest of humbugs.” In his failure to grasp the importance of the newest American works, Pach fell woefully out of touch with the contemporary art scene, which has undoubtedly contributed to the neglect of his legacy.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Pach was active as an art consultant, for not only private collectors, but also museums. For example, it was Pach who arranged for the acquisition by the Louvre of Thomas Eakins’s painting Clara (now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay). He orchestrated the purchase of Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Socrates by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and was the chief advisor to the Shilling Fund, an organization, founded in 1937, designed to support the work of contemporary American artists. In this capacity, Pach was responsible for acquiring paintings and sculptures by his colleagues and then placing them in museum collections across the United States.

Despite all these activities, Walter Pach considered himself to be primarily an artist, and his art developed in accordance with the major movements of his day. His early works reveal a painter steeped in the tradition of the Old Masters and trained to portray objects in a representational manner. Confronted with European modernism, Pach changed his way of painting and attempted to incorporate the new theories into his own style. After he explored cubist and futurist elements in his pictures, Pach reverted to realism around 1919. The development of his art echoed the main tenet of his aesthetic credo—evolution. He consciously strove to learn from the past and to incorporate the lessons of the masters into contemporary works that gave voice to the spirit of his time. Although the style and content of Pach’s paintings, watercolors, and etchings were not very original, his art was significant in that it addressed the vital issues of the day.

Walter Pach moved effortlessly among the leading art, intellectual, and literary circles of New York, Paris, and Mexico City in the first half of the twentieth century. Working behind the scenes, he strove to promote an understanding of and appreciation for the art of many different nations and eras, but had the most profound impact on the acceptance of modern art in the United States. He believed in the power of art to shape and affect people’s lives and through his persistent crusade to make art a vital part of life, Walter Pach won the hearts and souls of artists, collectors, dealers, and art enthusiasts the world over and earned a pivotal place as one of the most seminal figures in the history of modern art and culture.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.