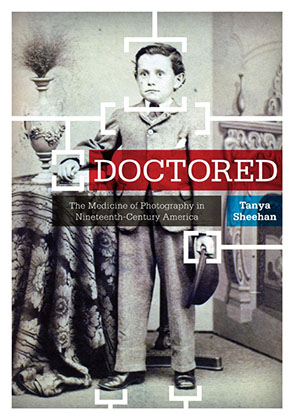

Doctored

The Medicine of Photography in Nineteenth-Century America

Tanya Sheehan

“In Doctored, Tanya Sheehan investigates the discursive intersections between photography and medicine in the late nineteenth century. Sheehan explores an understudied trove of professional photographic literature in order to understand the history of photography from its most popular practitioners’ point of view. This is a wonderful visual culture history.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“In Doctored, Tanya Sheehan investigates the discursive intersections between photography and medicine in the late nineteenth century. Sheehan explores an understudied trove of professional photographic literature in order to understand the history of photography from its most popular practitioners’ point of view. This is a wonderful visual culture history.”

“Doctored is a highly original and thoughtful study that illuminates the rich ties between nineteenth-century American portrait photography and medical practice. It illustrates how the nascent medium of photography gained legitimacy by forging ties to science and explores the deeply rooted belief in photography as a cure for social and even physical ills. The book makes a major contribution to our understanding of early photographic practice and its complex relationship to medicine, race, and class.”

“This remarkable book combines close readings of periodicals with theoretical acumen and interpretive insights, revealing the central role that medical metaphors played in American photographic culture in the nineteenth century. Conveniently embodying the desires and anxieties of both photographers and their clients, these medical metaphors were made manifest as much in advertisements, cartoons, and articles as in actual photographic portraits. Casting doubt on any hard-and-fast distinction between the social and the physical body, Doctored will change the way you think about this period of American history.”

“Tanya Sheehan’s Doctored is cultural history at its best, combining a magisterial examination of nineteenth-century photographic literature with a persuasive and nuanced argument about metaphor and photography’s discursive claims to professional expertise. A must-read for scholars of photography, art history, American studies, nineteenth-century cultural history, and urban studies.”

“Sheehan's Doctored adds an important confluence of science and art to published histories of photography. . . . With elegant endpapers and a unique but readable typeface, Doctored is a nicely constructed book. . . . The interdisciplinary nature of [Sheehan's] project makes it suitable not only for photo historians, but also for those interested in medical and scientific history, critical race studies, and cultural studies.”

“[Doctored] contributes as much to the history of ideas, or of language, as it does to the history of images.”

“Sheehan’s examination of medical photography in light of the larger dynamics of nineteenth-century photographic portraiture offers a way to integrate the history of medical photography with the history of Civil War photography.”

“In this highly original book, Tanya Sheehan showcases a vast, alternative narrative in which cameras were seen as scalpels, developing chemicals as therapeutic drugs, and photographers as ‘doctors of photography’ processing the ability to inspect, diagnose, and rehabilitate diseased and disordered bodies.

Doctored is a finely detailed examination of the social and historical factors surrounding photography’s use of medicine, grounded in latter nineteenth-century Philadelphia’s vibrant cultural brew.

Sheehan has given us an inventive book that illuminates our understanding of the body, both social and physical, and its role in the nascent years of photography.”

“In seeking to articulate and define their collective professional identity, nineteenth-century studio portrait photographers turned to medicine for inspiration, model, and metaphor. Tanya Sheehan masterfully and imaginatively presents this hitherto-unexplored avenue of defining photographic authority. . . . Doctored is decidedly a most welcome and handsome addition to the literature on the history of photography.”

“Sheehan’s book offers a breadth of perspectives on a very particular historical moment and theme that connects to the visual culture and social context of the time and enriches understandings of the historical emergence of photographic culture and its motivations.”

“Doctored, by Tanya Sheehan, draws fascinating connections between the early days of studio photography and established medical practices of the day. . . . [Sheehan] spends a great deal of time discussing the cultural history of Victorian Philadelphia, explaining not just the similarities between medicine and photography but also the general public view of photography and its impact on race relations as well as a person’s place in society. This book is just as much a historical account of Victorian American society as it is a history of the portrait photography industry.”

“Tanya Sheehan . . . provides a unique, innovative comparative study of the development of the relationship between portrait and medical photography in Philadelphia during the nineteenth century. . . . Sheehan effectively demonstrates how the past has strongly influenced the present, richly contextualizing the ‘doctoring’ of photographs.”

Tanya Sheehan is Associate Professor in the Art Department at Colby College.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Educating “Doctors of Photography”: Medical Models and the Institutionalization of Photographic Knowledge

2 Making Faces and Taking Off Heads: The Operations of Photography and Medicine

3 “Panes Curing Pains”: Light as Medicine in the Photographic Studio

4 A Matter of Public Health: Photographic Chemistry and the (Re)production of Healthy Bodies

5 Photo Doctors and Pixel Surgeons: The Medicine of Photography in the Digital Age

Appendix: Philadelphia Photographic Periodicals, 1864–1890

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Boys, come in and take your first medicine of photography.

—“The Humor of It,” Wilson’s Photographic Magazine (January 18, 1890)

In 1871, Henry Hunt Snelling made one of his first and most eccentric contributions to America’s premier photographic journal, the Philadelphia Photographer. Snelling explained that he had suffered from a persistent toothache for years, having undergone several unsuccessful dental operations and tried all of the available remedies. Then one afternoon, while he was working in his darkroom, a “good little invisible sprite” named “Doctor Photo” told him to put together a chemical prescription. This medicine, which relieved his pain completely, contained ether, iodide of potassium, bromide, and gun cotton—a combination that was “almost identical with the photographic collodion formulas of the present day.”1 After further experiment and a second visit from Doctor Photo, Snelling discovered that photography was in fact “the special physician” for a range of debilitating and seemingly incurable diseases that ravaged the bodies of photographers as well as the American public. The photographer, moreover, functioned as a “medium” whose divination of medical knowledge lent him the power to drive out the “evil” spirits of toothache, rheumatism, and neuralgia.

That Snelling had practiced photography for decades, written one of the earliest practical manuals on daguerreotypy, and edited two widely read photographic journals meant that readers of the Philadelphia Photographer, many of them commercial photographers, would have recognized him as an aging but reputable authority on photography.2 They were therefore prepared to read Snelling’s story not as the musings of a madman prone to hallucinations in his darkroom but as yet another of his serious meditations on the state of photography as a practice and profession. The story with which Snelling introduces his article encouraged such a reading, specifically by setting up Doctor Photo as an embodiment of commercial photographers’ aspirations for themselves and their work. Artists, he recalls, once “turned up their noses” at the idea that photography could rival painting, but now they “throw aside their prejudice, and choke down their pride, and seek the aid of the camera” in demonstrating to the public that their painted representations are artistic and true to nature; scientific investigations of nature have likewise been greatly aided by photography, proving that it is equally and intimately connected to “legitimate” sciences. What we find in Doctor Photo, Snelling concludes, is an entirely new social function for the medium, or what he calls the beginnings of “a phase . . . of photography not hitherto touched upon” that would radically redefine its relationship to art and science and transform the social identities of those who practiced it. Within this new phase of “photography as a physician,” the precarious health of Americans would come “entirely under the control of photography,” allowing the photographic profession, like Doctor Photo himself, to operate as a single body with potentially unrivaled authority.3

As fantastic as Snelling’s argument may seem to modern readers, the relationship between photography and medicine that his article proposes was by no means uncommon in nineteenth-century America. As photography was becoming increasingly popular in American cities at midcentury, commercial portrait photographers began constructing medical metaphors to describe the space of the urban photographic studio, the materials central to studio practices, and the physical and social effects of photographic operations. This practice became so pervasive in early photographic literature, in fact, that one rarely finds an issue of a trade journal without references to the photographer as “doctor,” his apparatus as “surgical,” or his chemicals as “diseased” patients. Portrait photographers also looked to medicine as a model for their institutional structures and their interactions with the studio public, which suggests to the cultural historian further similarities between doctors’ and photographers’ ways of knowing the body, the social value they attached to such knowledge, and the authority they sought to gain from it.

This book explores the ways in which these medical metaphors and models helped shape the social identities of urban studio photographers and the cultural identity of portrait photography between the late 1850s and 1890. By analyzing the trade and popular literature of photography and medicine alongside their visual and material culture, Doctored shows how the language and idea of “medicine” worked to strengthen the professional legitimacy of the commercial photographic community at a time when it was not well established. While photographers disagreed about what it meant to be part of a “profession,” many of their patrons assumed that they were “merely” mechanical laborers and that photography was a strange, and at times terrifying, technology. Faced with such internal and external challenges, those who took portraits for a living sought to become part of a cohesive group with a collective commitment, as one of them put it, to “elevating the character of the profession in the eyes of the public.”4 They found in their conception of medicine a means of representing themselves as professionals worthy of public respect and even social dependence.

The incorporation of medical metaphors and models into early photographic discourse did much more than promote the professionalization of commercial photographers, however. It lent them a specific kind of knowledge and authority—namely, the authority to manipulate, diagnose, treat, and ultimately heal the body—at the same time that it defined their field of operation, and that of photography itself, as the physical and social health of America’s urban public. Although the diverse social groups that inhabited America’s cities saw their bodies as vulnerable to physical disease, moral corruption, and various forms of social contamination throughout the nineteenth century, cultural historians have demonstrated that those perceptions were heightened during the period of this study, as Americans responded to regular epidemics of disease, vastly accelerated industrialization, steady waves of immigration and the racial and ethnic conflicts they fueled, as well as the carnage and consequences of civil war. While many cultural institutions, social reformers, and commercial entrepreneurs promised to foster a nation of healthy bodies that conformed to the ideals of whiteness and respectability, urban studio photographers, through their persistent relationship to medicine, portrayed themselves and their practices as both technically and socially suited to rehabilitating the “disordered” and “diseased.” Calls for photographers to study anatomy or to keep their studios clean, for instance, shaped their public image as educated and scientifically trained professionals who produced pleasing portraits of healthy subjects. Descriptions of the camera as scalpel and photographic chemicals as therapeutic drugs defined photography’s rehabilitative powers in terms of its unique ability to touch, penetrate, and even become the bodies of its subjects.

Rethinking Photographic Authority

For more than a century, historians of American photography have represented its first fifty years as a period when the fledgling medium strove to become a legitimate art. Their narrative begins with the 1840s, when photography’s first critics labeled it a mechanical process that did not require in its practitioners the intellect and imagination of fine artists. Determined to earn public recognition as legitimate producers of “high” culture, commercial photographers fought back in the decades that followed by increasingly incorporating the rhetoric and aesthetic conventions of the fine arts into their practices and establishing institutional structures based on artistic models, including photographic exhibitions, societies, and periodicals. They also made every effort to distinguish themselves from the hoards of amateur photographers who appeared on the American scene at midcentury, since amateur work, while generally respectful of aesthetic principles, threatened the legitimacy of photography as a serious artistic practice.5 After decades of struggle, the narrative concludes, American photographers ultimately won their battle. In the hands of full-fledged artists, photography entered the twentieth century as a widely recognized independent art form.

This story of the legitimization of photography as art began to take shape as early as the 1860s, when the preeminent Philadelphia daguerreotypist Marcus Aurelius Root proposed its trajectory in The Camera and the Pencil, or The Heliographic Art (1864).6 Root intended his book to provide practical instruction to his fellow commercial photographers, reflect on the status of photography in its first quarter-century, and outline his aspirations for the medium in the decades to come.7 Its use of the terms “heliography” (sun painting) and “solar pencil,” discussion of painterly concepts such as “expression” and “harmony of color,” and frequent quotation of such canonical painters as Raphael and Reynolds are a few of the ways in which Root emphasized the aesthetic character of the photographic medium and the artistic skills required of those who practiced it. His promotion of photography as a fine art was also supported by the commercial studios that bore his name (fig. 1). According to the photographs and prints of the Root Gallery that were made around the time The Camera and the Pencil was published, Philadelphians who rounded the southeast corner of Fifth and Chestnut streets would have seen the book’s claims confirmed in the form of a veritable “art gallery” whose second-floor windows were lined with reproductions of finely painted portraits that depicted equally fine ladies and gentleman.

Root’s artistic bias, which he shared with many of his contemporaries, articulated an important element of early portrait photographers’ aspirations for themselves and their work in the decades after photography’s invention. It continued to dominate historical surveys and practices of American photography into the twentieth century, from the writing of critics Charles Caffin and Sadakichi Hartmann and the pictorialist aesthetic they championed to the later modernist art histories of Beaumont Newhall and John Szarkowski, which celebrated the “art” of Alfred Stieglitz and his circle.8 Although these authors replaced the object of Root’s self-interest (commercial portraiture) with that of their own circles (landscape, amateur, and self-proclaimed “art” photography), they retained the daguerreotypist’s commitment to narrating the history of photography in terms of its development as a fine art. Early commercial photographs and their “artists” have once again become important subjects of critical analysis in recent decades, demonstrating that the historiography of American photography has yet to experience a sea change that would allow for other narratives of legitimization to structure the history of the medium.9 As Doctored demonstrates, however, a competing narrative did unfold in American photographic literature and defined urban studio practices in the second half of the nineteenth century. The portrait photographers who contributed to and consumed this literature became the architects and objects of a pervasive discourse aimed at legitimizing photography not exclusively as art but as a science of the body.

Examining the centrality of medicine to this discourse introduces new ways of thinking about the sources of and challenges to photographic authority in the period of its initial formation. I speak here of two kinds of photographic authority: professional, which is closely tied to the body of the photographer, and representational, which implicates the body of the sitter. To do so is itself to challenge several widely held assumptions in the critical historiography and theory of photography, including the notion that neither a sociological nor a historical analysis of photographic authority is possible. As Allan Sekula and John Tagg proposed in the 1980s, portrait photography’s character has been (re)produced through the historically specific institutions, discourses, and practices in which the technology has been embedded.10 The idea that a photograph is existentially bound to its referent and thus a marker of the real is, as a result, not an essential characteristic of the photographic medium; rather, it is a cultural belief constructed in a particular time and place that powerfully effaces the work that has brought it into being.11 Adopting this methodological position, Doctored assumes that a consideration of social and historical phenomena—from the rise of a new professional and consumer culture to the redefinition of citizenship that took place during the Civil War and Reconstruction periods—is inseparable from any critical history of photography. Building upon recent scholarship on early commercial photography in the field of American studies, this book sets out to show how these changes to the American cultural landscape informed studio photographers’ use of medical metaphors and models while contributing to the larger analogies between portrait photography and medicine that emerged from them.12

Doctored also challenges a tendency among historians of photography, even those attentive to social context, to define photographic authority exclusively as the so-called objectivity of the photographic image. This book demonstrates that in nineteenth-century America the perceived rehabilitative powers of portrait photography were just as important as its “reality” when it came to defining the medium. Public perceptions of those powers, moreover, depended as much on the appearance, knowledge, language, and skills of portrait photographers as they did on photography’s apparent ability to heal the body; as a result, analyzing photographers’ bodily performances and professional discourse becomes crucial to understanding the authority of their visual practices.13 To that end, Doctored focuses on photographers’ actions and statements within commercial photographic literature and the urban portrait studio. It shows how medical metaphors and models encouraged studio patrons to trust “doctors of photography,” and the character of their portraits, in a period when middle-class Americans wanted to see doctors as honorable gentlemen whose manipulations and treatment of the body could remedy their perceived ills.

It is important to recognize, however, that not all doctors conformed to this ideal type in the nineteenth century, when American medicine was regularly challenged as a profession and ineffective as a practice. These historical facts alone called into question the power of all medical references when they were most prolific in photographic discourse, or at least rendered that power ambivalent in certain contexts; what is more, the specific types of medicine to which studio photographers compared their practices were very often the objects of popular criticism. In fact, a satirical print published in the American comic magazine Puck in 1881, titled Death’s-Head Doctors.—Many Paths to the Grave (fig. 2), includes in its illustration of quackery the medical models most commonly invoked in early photographic literature, the same models that are examined in this book: operative medicine (in the form of surgical amputation), phototherapy (General Pleasonton’s blue-glass cure), and pharmacy and therapeutics (a variety of pills and potions). Many of photographers’ business practices, moreover, associated them less with orthodox or “regular” physicians than with “irregulars”—those who, in the world of Puck, promoted homeopathy, hydrotherapy, folk remedies, magnetic cures, and patent medicines. Like these popular practitioners of alternative medicine in nineteenth-century America, few portrait photographers spent enough time with a “patient” to establish an ongoing relationship or history; photographers were also excellent salesmen who promised miraculous and pain-free results, generally believed that newer materials were necessarily more effective than old ones, made an elaborate show of their credentials, and relied on the authority of others for their credibility.14

Photographers certainly ran the risk of representing their operations as socially destabilizing and even life-threatening by explicitly or implicitly associating them with irregular medicine, much of which the professional medical community of the period deemed quackery. Doctored argues that the massive popularity of these popular remedies among the American middle class nevertheless had the potential to provide studio photographers with the kind of authority they sought. In a period when American medicine was undergoing a widespread professional crisis, what mattered was that photographers’ medical models incorporated the appearance and rhetoric of science while satisfying middle-class desires for easily accessible, allegedly fast-acting, and relatively inexpensive rehabilitations of the body. It was this same social group that eagerly consumed and put stock in alternative medicines—the group, in other words, that photographers were most concerned to attract to their studios and hoped would believe in the rehabilitative powers of their practices.

Informing these explorations of photographic authority is another important intervention in the historiography of photography, one that recasts the relationship between photographic portraiture and medicine in nineteenth-century America as mutually constructive. Focusing on clinical photographs of doctors and their patients, previous scholarship has represented photography as instrumental to medicine, particularly to medicine’s emergence in the modern period as an authoritative epistemology and practice, which was tied to the development of its professional and scientific character.15 Doctored revises, and in a sense reverses, this order of things by understanding medicine as central to the “marketplace strategies” of commercial portrait photography—strategies that medical historian John Harley Warner has described as directed toward the acquisition of “cultural authority and professional success.”16 While Warner and others have represented American doctors in the mid- to late nineteenth century as attempting to buttress the authority of their unstable profession through their use of photography, this book shows how studio photographers’ reliance on medical discourse worked to bail them out of a similar professional crisis; this, in turn, helped stabilize the authority of medicine as well as shape the scientific character of the photographic medium, which medical historians have argued made it such an attractive tool for nineteenth-century doctors.17 Professional borrowings, such as those between portrait photography and medicine, therefore had doubly creative potential, in that complex negotiations gave shape to both sides of the relationship.

Just as important as the instrumental character of that relationship, which is embodied by the genre of clinical photography, is the presence of the “medical” in all forms of commercial portrait photography in the nineteenth century. As several theoretically informed histories of medical imaging have proposed, a genealogical relationship existed between self-consciously medical and vernacular portraiture as well as between photographic technologies and medical practices, which accounts for their similar ways of representing the body as diseased and hence as an object to manipulate, analyze, and control.18 Doctored takes these observations as a starting point, extending their implications to the historically and culturally specific study of studio photography in American cities. At stake in its mobilization of the history of medicine and critical theories of the photographic image is a new understanding of photography’s “medical” roots as constructed in a particular time and place and operating outside, but always in relation to, the spaces, apparatuses, and procedures of modern medicine.

The Work of Medical Metaphor

In its close readings of early photographic literature, Doctored assumes that medical metaphors represent more than a creative use of language and actually serve as a means of structuring thought and action. George Lakoff and Mark Johnson advanced this view in their highly influential study Metaphors We Live By (1980), which argues that the “primary function of metaphor is to provide a partial understanding of one kind of experience in terms of another kind of experience.” That is to say, while portrait photography and medicine refer to different “experiences,” in the second half of the nineteenth century the former was “partially structured, understood, performed, and talked about” in terms of the latter. When we speak of the medicine of photography, moreover, we are referring not only to a particular linguistic expression but to an ontological and epistemological mapping from the “conceptual domain” of medicine to the “target domain” of photography.19 This restructuring could be expressed in many varieties of figurative language, and indeed it was in the historical period Doctored examines, most often taking the form of traditional metaphors, similes, analogies, and personifications.20

Important to my analysis of these forms is Lakoff and Johnson’s claim that metaphorical concepts are only ever partial—that is, they highlight selected aspects of an experience or concept and hide others—since it accounts for the coexistence of the multiple metaphors for photography observed by its historians; each of these brought to light different characteristics of the medium that spoke to competing, culturally specific ideas about what it could be and do. As Geoffrey Batchen demonstrates in his survey of the labored efforts to name photography before 1839, its inventors constructed a “mass of metaphor” before settling on the albeit uneasy combination of “light” and “writing” that foregrounds the medium’s simultaneous connection to nature and manual production.21 Alan Trachtenberg has similarly approached the figurative language in early critical responses to the daguerreotype in the United States, observing that the common notion of the “photograph-as-mirror” articulated the daguerreotype’s affinity with the black arts as well as its capacity to stand for both “truth and deception.” 22 My own work points to the ways in which the medicine of photography largely downplayed the medium’s connections to natural forms, fine-artistic practices, and magic while emphasizing others that resonated with the desires and anxieties of those who produced and consumed it between the late 1850s and 1890. This metaphor specifically implied a vision of photography as a technology or material that operates within the field of the body by acting directly upon bodies; it further assumed an investment on the part of photography and its practitioners in the eradication of disease and the promotion of health.

Contemporary theories of metaphor also have much to offer in understanding how and why particular figurative conceptions of photography come into being. The idea that metaphors are not arbitrary but are grounded in physical experience, for example, has led scholars to observe their basis in material fact; the daguerreotype is a mirrorlike reflective surface that reverses the image it represents, just as the proliferation of “light” metaphors in writing on photography continues to be based on the medium’s means of production.23 The primary texts discussed in this book likewise identify basic points of connection between the material practices of commercial portrait photography, which involved dressing, posing, and lighting bodies in the studio, and the wide range of corporeal manipulations associated with medicine, from administering oral, topical, and indeed light treatments to bandaging wounds and amputating diseased limbs. These preexisting connections provided the motivation and groundwork for the emergence of the medicine of photography, which in turn created new relationships between portrait photography and medicine that affected how the former was perceived, talked about, and practiced in nineteenth-century American cities. Cast in Lakoff and Johnson’s terms, medical metaphor had a hand in defining photography as a coherent idea and in shaping the “realities” of photographic experience by guiding the thoughts and actions of studio photographers and their patrons in both conscious and unconscious ways.24

Doctored further draws upon scholarship that recognizes the important contributions metaphorical concepts can make at key moments in the history of a technology. Reflecting on changes in the medium of film at the turn of the twentieth century, for example, Tom Gunning has observed that the “introduction of new technology in the modern era employs a number of rhetorical tropes and discursive practices that constitute our richest source for excavating what the newness of technology entailed.”25 Attending to the figurative language associated with the advent or redefinition of a new medium, in other words, enables the historian to see what was novel, surprising, and even strange about it. Gunning’s observation also suggests that the timing of medical metaphors for photography was anything but random; indeed, seen from a technological perspective, they first emerged in commercial photographic discourse precisely as new formats like the carte de visite and the tintype were making studio portrait photography increasingly available to a broad American urban public, and when that social group was struggling to make sense of the medium’s aesthetic conventions and effects on the body. While photographers’ investment in the photographic marketplace differed substantially from that of studio patrons, in the decades after the medium’s invention they, too, disclosed the strangeness of their practices through metaphor, often in the form of medical humor; the epigraph with which this introduction begins is one of many such examples that the reader will encounter in the pages that follow.

Building upon anthropological and sociological studies of metaphor, Doctored acknowledges a degree of self-interestedness on the part of commercial portrait photographers in the construction of photography as medicine. Their expressions of this metaphorical concept, in other words, constituted creative acts typical of a social group that desires power, specifically one seeking to establish its professional legitimacy and incorporate its practices into a well-defined system of knowledge with widely recognized social value. Within this scenario, the commercial photographic community attempted to further its professionalization by aligning itself with a social structure that dominant culture deemed “natural” and granted considerable authority; analogies facilitated this process by transferring aspects of the preexisting group onto the burgeoning group and proposing a resemblance between the two.26 The primary objects of analogy for many aspiring professions in modern America were, in fact, the social relations they associated with medicine, relations that doctors worked hard to naturalize through a similar set of procedures throughout the nineteenth century. JoAnne Brown speaks of this trend in The Definition of a Profession (1992) by observing that social workers, engineers, and psychoanalysts have all practiced what she calls a “linguistic mimicry and modeling” of medicine during their respective periods of professionalization. The subjects of her case study, American psychologists of the early twentieth century, “compared themselves to medical doctors, mental and social problems to bodily disease, and their methods, such as the ‘IQ’ test, to diagnostic instruments like the thermometer, the x-ray, and the blood count.”27 Viewed in this context, commercial photographers can be seen as participating in a widespread professional practice in modern America by adopting language ordinarily associated with medical men.

While acknowledging that many groups found in medicine a language in which to articulate and promote their social aspirations, Doctored is also concerned to elucidate the peculiar character of medical metaphor making in the history of photography. One aspect of this character has already been touched upon—namely, the fact that photographers compared their practices to both orthodox and alternative forms of medicine, including popular treatments that the American medical profession, then and now, would consider quackery. As the chapters in this book argue, different forms of medicine became associated with different kinds of work in early portrait studios—manipulating bodies, operating the camera, adjusting the lighting conditions under the skylight, retouching negatives, developing prints—and thus enabled the construction of different kinds of photographic authority. In addition, unlike the actors in Brown’s case study, both studio photographers and their patrons regularly challenged the apparent dissimilarities on which their metaphors were based. Unsurprisingly, photographers’ representation of photographic knowledge and operations as more like those of doctors than not functioned as a powerful professional strategy. The public’s interpretation of the medicine of photography as a literal comparison between two identical objects, by contrast, tended to emphasize the absurdity of this concept, threatening to undo the positive work it could perform for the commercial photographic community. The construction of photographic authority thus involved a continuous (re)invention of the basis of medical metaphors and careful management of their complex and multifarious meanings—a difficult if not impossible task.

In addition to collecting and characterizing the many explicit metaphors made by those who encountered photography in nineteenth-century America, I see the job of the cultural historian as seeking out the deep structural similarities between different cultural practices within a given historical period, constructing a shared group of rules that orders their subjects (a discourse), and defining the system that enables and governs the particular set of relations between their distinct elements and statements (a unity of discourse).28 As Michel Foucault argued in The Order of Things, these similarities are “hidden” from historical actors not because of their intellectual inability to perceive them but because analogies have been crucial to the establishment of systems of knowledge and representations of the social order throughout the modern period; this work was necessarily unconscious at the time of their production—or, if conscious, the awareness was “superficial, limited, and almost fanciful.” Adopting this Foucauldian paradigm, Doctored proposes figurative relations of its own to demonstrate that studio photographers and medical doctors in the nineteenth century often “employed the same rules to define the objects proper to their own study, to form their concepts, to build their theories.”29 These points of connection, I argue, helped establish photography as a discrete concept and institution while contributing to the formation of a cultural discourse on the diseased and disordered body in urban America.

One important analogy that this book proposes between portrait photography and medicine concerns the ways in which these technologies continually negotiated what anthropologist Mary Douglas has described as “two kinds of bodily experience”: the physical and the social. In Douglas’s terms, we can say that the human body in commercial photographic and medical discourses functioned similarly as “an image of society,” such that its physical boundaries, potential, and weaknesses corresponded to ideas about social boundaries, potential, and weaknesses on both an individual and a collective level.30 Or, to return to Foucault’s model of cultural history, we can see photographers’ and doctors’ struggles to control the bodies in their care—to ensure that they realized their maximum potential, maintained their health, shored up their boundaries, and ultimately remade their appearances—as expressions of social control and commentaries on the social order.31 Bringing these paradigms into dialogue with each other, Doctored interprets the representations of sitters’ bodies in early photographic discourse as vulnerable, unruly, and in need of rehabilitation in relation to a disordered public body during and after the American Civil War. Efforts to control bodies in urban portrait studios through specific rhetorical and mechanical means, moreover, attempted to remake individuals, the city, and the nation, and to establish a professional body of photographers as a powerful agent of social change.

This connection between physical and social health brings portrait photography into dialogue with American political discourse, which has long been rich in medical metaphor. In the years during and immediately after the American Revolution, political leaders and theorists such as Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, and Thomas Paine frequently portrayed American society, and particularly its system of government, as a body prone to illness that could benefit from the therapeutic effects of the war, the subsequent creation of the American Republic, and the maintenance of a strong Constitution. According to the historian Martha Banta, these representations can be divided into two categories, “that of infections requiring quarantine to check their spread and that of therapies based either on heroic methods of interference or on devices that credit the self-limiting nature of disease.”32 They are common, moreover, in the political writings and speeches that Banta surveys as well as in the visual culture of the period. So we find that in 1774 Paul Revere famously distributed a British etching titled The Able Doctor, or America Swallowing the Bitter Draught, which depicts a British minister forcing the tea tax down the throat of a half-naked, female America, while less than a decade later Thomas Jefferson compared the “mobs of great cities” to “sores” that weaken the human body because of their lack of support for “pure government”; “degeneracy” in the “manners and spirit of a people,” Jefferson added, “is a canker which soon eats to the heart of [a republic’s] laws and constitution.”33 Such references remained popular in the nineteenth century, especially at the time of the Civil War, when Abraham Lincoln compared slavery to a cancer on the nation that had to be excised with extreme care, lest the afflicted patient bleed to death under the “surgeon’s knife.”34 Picking up on Lincoln’s fondness for medical metaphor, the American editorial cartoonist Thomas Nast published in an 1862 issue of the New-York Illustrated News his visual commentary on the socially therapeutic benefits of the president’s proposal for a gradual and voluntary emancipation of black slaves in the southern states (fig. 3). Depicting Lincoln holding a cup to the mouth of an African American in his sickbed, Doctor Lincoln’s New Elixir of Life suggests that the “elixir” of emancipation would bring social healing to the South and its black population, and ultimately to the national body.

It was at the same moment that Lincoln and Nast were reinvigorating the tradition of imag(in)ing America as an ailing body that urban portrait photographers were increasing their trade in medical metaphors, portraying their profession, their patrons, and even their materials as “bodies” in urgent need of “medical” care. In strikingly similar ways, “photographic” and “political” communities in the Civil War and postbellum periods envisioned an intimate relationship between the individual and the collective, such that the health of a photographer, middle-class sitter, politician, or American citizen was shaped by and contributed to that of the photographic profession, the middle class, the political process, and the nation itself, respectively. In addition to noting photographers’ explicit references to the war and other threats to the U.S. government in their trade literature, Doctored sets out to demonstrate that much of their medically inflected writings were deeply political, in the sense that they reinforced dominant contemporary constructions of class, race, and nation.

Philadelphia: A Middle-Class City

Doctored reconstructs the historical and cultural foundations of the medicine of photography within the specific context of mid- to late nineteenth-century Philadelphia. Along with Boston and New York, Philadelphia in this period was home to the country’s preeminent medical institutions.35 In the field of American medicine, however, it had long been a city of firsts: most notably, the Pennsylvania Hospital was the nation’s first hospital (1751); the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (1765) and Jefferson Medical College (1824) were its first and second medical schools, respectively; the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (1767) is its oldest professional medical organization; the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (1821) was the first American institution to offer a professional pharmaceutical education; and the American Medical Association, founded in Philadelphia in 1847, was the country’s first national medical society.36 These institutions both attracted and fostered some of the most celebrated figures in modern American medicine, including Benjamin Rush, Philip Syng Physick, Samuel Gross, David Hayes Agnew, William W. Keen, S. Weir Mitchell, and many others, who together made invaluable contributions to every branch of medicine.

In the words of one of American photography’s earliest historians, Julius F. Sachse, Philadelphia was also “the birthplace of photographic portraiture as well as the mother city of modern photography.”37 Most histories of the technology’s development credit Philadelphians with making the first American daguerreotype in October 1839 (Joseph Saxton), inventing the bromide process that made daguerreotype portraiture possible (Paul Beck Goddard), and shortly thereafter producing the world’s first (surviving) photographic portrait (Robert Cornelius). Philadelphia photographers also opened the first photographic studio in America, and perhaps in the world, in 1840 (Cornelius again) and established one of the earliest photographic societies in 1860 (the Photographic Society of Philadelphia), in addition to publishing the first historical account of the medium in the United States in 1864 (Marcus Aurelius Root), and the country’s most widely read photographic journals before the turn of the century (Edward L. Wilson).38 That the city was unique in witnessing the technical development of both medicine and portrait photography in the nineteenth century, along with the professional advancement of doctors and studio photographers, makes Philadelphia and its institutions an ideal site of investigation for this study.

Much of Doctored focuses on the geographical, commercial, and cultural heart of Philadelphia now known as Center City, which is bounded by Vine Street to the north, South Street to the south, the Delaware River to the east, and the Schuylkill to the west (see wards 5 through 10 in fig. 4). During the period it considers, this area contained businesses and private residences primarily in three- and four-story brick row houses situated on a rigorously ordered grid of horizontal and vertical streets. An engraving of Chestnut Street published in Baxter’s Panoramic Business Directory of Philadelphia (fig. 5) shows us just how many photographers operated on a single block of one of the most fashionable commercial streets in Center City in 1859. Amid shops that sold gas fixtures and housewares, a gentleman’s clothing store, importers of women’s hats and dresses, a manufacturer of spectacles, and a commercial penmanship service, Philadelphians encountered as many as four portrait studios: (from left to right) Germon’s; the firm of Fredericks, Penabert and Germon; Spieler’s; and Dinmore’s. Many of the city’s best-known and most respected portrait photographers established their businesses elsewhere on Chestnut, among them Marcus Aurelius Root, the Langenheim and McAllister brothers, Samuel Broadbent, Montgomery P. Simons, James McClees, and F. A. Wenderoth; other high-profile photographers, such as W. L. Germon and Frederick Gutekunst, operated on nearby Arch Street, while clusters of both large and small-scale studios could be found on Market, Walnut, Vine, Eighth, and Ninth. In addition to signaling the vigor with which Philadelphia photographers promoted their work, the advertisement for George Rau’s Photographic Rooms printed on the map in figure 4 reminds us that portrait photography was also flourishing in the districts, boroughs, and townships just outside Center City; situated at 922 Girard Avenue in the Penn district (ward 20), Rau’s studio was perhaps the most prominent photographic establishment to serve this busy commercial street. In 1854, when the Act of Consolidation incorporated the Penn district, along with twenty-eight other wards, into the boundaries of the “city,” bringing them under the control of a centralized government, more than three hundred photographers worked in Philadelphia, most of them commercial daguerreotypists; by 1890 approximately 120 photographic studios were in operation, producing portraits in a wide variety of formats.39

Crucial to my understanding of the photographic profession, its public, and its material and rhetorical practices is the social fabric of the city. Although intended to facilitate the enforcement of law and order, the consolidation of Philadelphia in 1854 brought social tensions to a city already troubled by economic depression and labor strikes as well as racial and ethnic conflicts. In the 1840s Philadelphia had experienced a massive population increase due to the immigration of rural Americans from Pennsylvania and the mid-Atlantic states, runaway slaves and free blacks, and poor immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and other European countries who settled in the city and county of Philadelphia. The strain this increase placed on Philadelphia’s resources and the clash of social identities and values that it produced encouraged the city’s “native” white Protestants to assert their dominance over “nonnative” groups through legislation, public protests, and a series of violent race riots. Their efforts to preserve the racial and economic homogeneity of “the birthplace of America” were largely unsuccessful, however, as “nonnative” immigrant groups continued to be attracted to, and to help shape, the rapid urbanization and industrialization of Philadelphia in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. It was out of these patterns of social movement and conflict that Philadelphia became the world’s fourth-largest city in this period, experiencing a sevenfold increase in its population that can be accounted for only in part by the act of 1854. Before the turn of the century, Philadelphia’s population doubled again, exceeding one million.40

For the majority of “native” Philadelphians, the consolidation of the city that took place in the period of this study meant joining together its separate parts with very little possibility of constructing a unified organic whole. They envisioned a solidification and strengthening of the city, and by extension of the nation, that involved excising parts they deemed weak or unwanted and reorganizing those that remained. Behind this vision stood a fantasy of respectability that was synonymous with whiteness and health and that informed every aspect of the dominant culture and public life in Philadelphia, as it did in many other large American cities of the period. The visual representations of Philadelphia’s commercial district in directories like Baxter’s are only one means by which desires for social “sanitization” found popular and insidious expression; one cannot help but marvel at the armies of uniformly white, top-hatted, and petticoated bodies in these images, given the mix of social types that historically occupied the homes, businesses, and streets of the great American metropolis. One of the goals of this book is to present commercial portrait photography as a rising profession and practice that gave material form to this vision of the city and its people as ideally white and middle class, in part through its sustained dialogue with medical discourse.

Social historians, from Stuart Blumin to John Hepp IV, have portrayed Philadelphia not only as a typical “middle-class city” but as one that exemplified middle-class urban culture in modern America.41 This is not to say that the city’s many lower-class and elite inhabitants did not significantly shape its rich history and culture, but rather that life in Center City was organized in the nineteenth century around the values and desires, as well as the daily routines and social networks, of the middle class. According to Blumin, a “relatively coherent and ascending middle class,” a distinct social position between the “poor and ‘inferior’ inhabitants of the city” and the “members of the mercantile elite,” began to take shape in the early nineteenth century and was fostered by decades of industrialization, urbanization, and institutionalization. In Philadelphia and other large northeastern cities, Blumin explains, membership in this growing middle class depended both on one’s economic wealth and on the nature of one’s work, given that a social stigma was associated with even the most skilled forms of manual labor. Like other categories of identity, of course, class was also socially constructed and publicly performed through one’s daily interactions in the theater of the city; it both defined and was defined by “a specific set of experiences, a specific style of living, and a specific social identity.”42

The urban portrait studio was one social space in which Philadelphians could participate in the construction of their own gendered and raced class identities in relation to the ideal norms of the dominant social group. In part, their participation was conscious, in the sense that many commercial photographers and their patrons were keenly aware that their work habits, social interactions, and physical appearance called perceptions of their identity into question. Photographers acted upon this knowledge by taking measures to professionalize their work and self-image, linking the elevation of their social status with that of idealized medical men; sitters, in turn, trusted these would-be professionals to portray their bodies and “selves” as legibly respectable and, in most cases, visibly white. Returning to the engraving in Baxter’s, one might argue that every shopkeeper on that stretch of Chestnut Street was in this business of self-(re)making. While most provided clothing and home furnishings suitable for men and women of proper social standing, commercial portrait photographers manipulated lighting and exposure, prop and pose, offering Philadelphians of all economic and ethnic backgrounds seemingly truthful, permanent, and circulatable visual records of their “white middle-class” selves. How conventional studio portraits in the nineteenth century, from daguerreotypes to cabinet cards, helped construct the social identities of their sitters is a question that historians of early American photography have recently been keen to explore.43 Their responses have invigorated new interest in commercial photography and its practitioners, photographers’ trade literature, and the material practices of the portrait studio, at the same time that they have laid the groundwork for new areas of inquiry. Stepping into this space, Doctored asks how photographers were implicated in and affected by the processes of identity formation that scholars have associated with the production of commercial photographic portraiture. How were photographers and sitters able, both in their own ways, to manipulate those processes to further their own social elevation (or not)? Finally, how was the identity of the photographic medium itself constructed as a result and in relation to other technologies of the body that functioned as instruments of physical and social rehabilitation in modern American culture?

The National City and the Civil War

The preoccupation with rehabilitation that runs through this book and the commercial photographic discourse it explores speaks directly to the vital role that Philadelphia played in the Civil War. As J. Matthew Gallman recounts in his in-depth social history of wartime Philadelphia, the city was the Union’s second-largest and a major contributor of men, materials, and other much-needed support. Most “able” Philadelphians who were white, male, and between the ages of eighteen and forty-five—between eighty and a hundred thousand out of a total 138,000 men in this group—served in the Union army.44 Many who did not enlist, including a significant group of white middle-class women, participated in the war effort by raising funds through the city’s many volunteer societies. Their largest project, in terms of physical and economic scale, took the form of the Great Central Fair in June 1864, which aimed to assist the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) in its mission to provide supplies for and oversee the proper care of Union soldiers. Held in a temporary exhibition space in Logan Square—“constructed and decorated,” art historian Elizabeth Milroy has observed, “to elicit patriotic fervor and national pride”—this event attracted more than four hundred thousand visitors to its display of domestic and manufactured goods, military and farm equipment, artworks, and curiosities donated by the residents of the Delaware Valley.45 In addition to raising more than a million dollars for the USSC, the Great Central Fair created a utopian national space—literally bedecked in red, white, and blue—in which every Philadelphian (who could afford the not insignificant price of admission) imagined that he or she was contributing to a northern victory through material production and consumption (fig. 6).

Despite the fact that a battle never took place on city soil, Union troops were continuously present there, many of them in desperate need of medical care. Early in the war, the U.S. government had designated Philadelphia as a primary site at which it would treat the sick and wounded owing to its size, its geographical location on the Union’s southern border, and its major port and railroad lines. As the president of the USSC proclaimed before a large audience of Philadelphians in 1863, no city in the country had “been nearer to the seat of the war, and more directly in contact with the great highway to the army. Every soldier almost who has been to the war, at least in the Eastern Department, has been obliged to cross your threshold.” The welcome and care that each received there, he continued, left “the stamp of this city on his heart,” thanks to the efforts of volunteers who provided hundreds of thousands of soldiers in transit with meals, clothes, beds, and bathing facilities in refreshment saloons as well as in shops and taverns converted into temporary medical facilities.46 When these facilities were unable to accommodate the injured pouring into the city from the battlefield, a network of military hospitals was created. The largest of its institutions, Mower General Hospital, was built across from the Reading railroad depot in Chestnut Hill, eclipsing the already sizable Satterlee General Hospital, located in West Philadelphia. By the end of the war in 1865, Philadelphia’s nearly two dozen military hospitals had offered six thousand beds to the 157,000 soldiers who received medical treatment in the city.47

The regular sight of wounded, disfigured, and otherwise ailing bodies in virtually every corner of Philadelphia during and after the Civil War had an enormous impact on its citizens, institutions, and cultural practices. Historians have examined this impact by pointing to the preoccupation with corporeal disorder in medical and popular literature of the period, which imagined an intimate relationship between physical, psychological, and national disease.48 Many of these scholars have pointed to the intimate relationship between these types of disease in the writings of S. Weir Mitchell, who performed surgical operations during the war at Philadelphia’s Filbert Street Hospital before devoting himself to the study of postoperative nerve diseases at Turner’s Lane General Hospital. In “The Case of George Dedlow,” a fictional first-person narrative based on Mitchell’s experiences in these institutions, the title character reflects upon his experience of losing his limbs to gunshot wounds and gangrene, which lands him in Philadelphia’s “Stump Hospital” on South Street. Through the eyes of a quadruple amputee who imagines that he is nothing more than “a useless torso, more like some strange larval creature than anything of human shape,” Mitchell observed the “horrible variety of suffering” that the battlefield inflicted upon Union soldiers, their families, and the national body they fought to preserve.49

Commercial photographers also responded to this widespread perception of bodies in pieces during and after the war, taking as their aim not only the depiction of the wounded but the restoration of physical and national health. As Alan Trachtenberg and Joan Burbick have argued, publicly exhibited battlefield photographs representing the “mutilated remains” of fallen heroes forced the middle-class Americans who viewed them to confront the corporeal realities of the conflict and imagine the redemption of a dismembered United States. Reflecting upon Matthew Brady’s Antietam photographs in 1863, the physician-photographer Oliver Wendell Holmes saw in these images a powerful means of representing war as “repulsive, brutal, sickening, [and] hideous” that pointed to both the cause of and treatment for America’s ills. “Where is the American, worthy of his privileges,” he wrote in the Atlantic Monthly, “who does not now recognize the fact, if never until now, that the disease of our nation was organic, not functional, calling for the knife, and not for washes and anodynes?”50 Clinical photographs of soldiers who survived the conflict—the victims of fractured and shattered bones, disfigured flesh, and infected tissues—similarly performed a dual documentary and therapeutic function. Portraying grotesquely injured soldiers before and after medical intervention, the photographic studies undertaken for the Army Medical Museum, considered in chapter 2, demonstrated that debilitated military bodies, along with the nation they both symbolized and served, could return to a state of health.51

What Doctored adds to existing scholarship on Civil War photography that takes such images as its subject is a fuller understanding of the ways in which the “everyday” practices of urban commercial portraiture aimed to contribute to the national project of rehabilitation. At the broadest level, the chapters that follow reframe the boom in the commercial photographic industry that took place in Philadelphia between 1860 and 1866—a staggering 450 percent increase in the total manufacturing output for photographs and materials—as connected to the contributions photographers and their patrons imagined photography could make to the war.52 More specifically, they interpret the commonly acknowledged relationship between medical and vernacular studio portraiture in the 1860s and ‘70s as much more than a matter of shared aesthetic conventions by observing that their points of connection stem from a similar way of envisioning bodies—as diseased, disordered, but essentially operable—that would dominate the cultural imagination of the postbellum city.

Bodies of Literature

The primary evidence that Doctored mobilizes to this end consists of a vast yet understudied body of photographic literature produced and/or consumed by Philadelphians in the second half of the nineteenth century. Because they constitute the most widely read texts on the subject of American photography at the time, I focus on the photographic trade journals founded and edited by Edward L. Wilson (1838–1903). Wilson began his work in the field of photography in the early 1860s, when he assisted Frederick Gutekunst in his internationally known Philadelphia studio; he went on to make enormous contributions to the professionalization of photography in the United States by co-founding the largest publisher of texts for the American photographic community, organizing the National Photographic Association in 1868, overseeing the production and display of photography at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876, and writing several important photographic manuals between 1881 and 1893.53 During this time Wilson was able to exert perhaps his greatest influence on the development of the photographic profession in his role as editor of the Philadelphia Photographer, the two periodicals it absorbed (the Photographic World and the Photographer’s Friend), its annual review (Photographic Mosaics), and its successor (Wilson’s Photographic Magazine).

Described in the appendix to this book, Wilson’s journals were published for most of their existence in Philadelphia and were read by most of the city’s practicing photographers. The Philadelphia Photographer in particular also had a large circulation within other urban photographic centers in the United States, such as New York, Boston, Chicago, and St. Louis, whose photographic societies published reports of their activities in its issues. Like Wilson’s other publications, the journal additionally printed international photographic news contributed by foreign correspondents. To speak of the “Philadelphia photographic community” that Wilson helped construct in the second half of the nineteenth century is to speak of a nearly all-white and all-male fraternity of photographic studio owners and operators, instructors and students, as well as suppliers and buyers who lived and worked within and beyond the boundaries of consolidated Philadelphia. The individual photographers and studios named in Doctored therefore have ties to a variety of geographical locations but share a common connection to Philadelphia through their consumption of and contributions to the city’s photographic literature.

It should come as no surprise that relatively little attention has been paid to this body of writing in the histories of photography, given that scholars have long privileged self-consciously artistic over commercial photographic production. As Steve Edwards explains in his recent study of the relationship between art and industry in English photographic discourse, moreover, the “strange, hybrid literature” that includes Wilson’s journals can be “difficult to unpack,” given that it often articulates competing positions and interests and juxtaposes artistic theories with what modern readers might see as banal and technical minutiae.54 Published anonymously or under pseudonyms and generally lacking “critical moments of rupture,” articles in these journals also deny scholars the opportunity to attribute eloquent, paradigm-shifting statements to individual authors whose names can be found on (or easily added to) the growing list of “master” photographers that has constituted the (art) history of photography since the early twentieth century.

Like Edwards, I aim to construct a different kind of photographic history, one that privileges the “incessant, everyday speech of photographers” articulated in their trade literature.55 The chapters that follow read texts in this genre as one might critically interpret works of fiction—that is, by offering close readings of their narrative structures, points of view, themes, characters, style, and figurative devices. To read photographic literature as fiction, in other words, does not involve denying its basis in “reality” or its importance in disseminating factual information about the practice of photography, whether that information concerns cyanide poisonings in the darkroom or the technical difficulties that photographers faced when lighting dark-complexioned sitters. Rather, it involves asking, how were these “facts” constructed through any number of literary elements in the text? And how can such formal analysis inform, while being informed by, an understanding of the social and historical contexts in which the text was conceived, published, and consumed?

Because Doctored situates portrait photography in relation to other technologies and discourses, literatures other than “photographic” serve as valuable objects of analysis. This is especially the case for Philadelphia’s medical literature, which is as eclectic as the medical metaphors and models through which nineteenth-century portrait photographers and their patrons imagined photographic practices. The examples discussed in the following chapters range from journals such as the Philadelphia Medical Times, which circulated widely among members of the American medical profession, to clinical handbooks for surgeons and medical students that were published in the city, to advertisements for locally produced pharmaceuticals, to treatises on alternative and home remedies written by well-known Philadelphians. The city’s popular literary and domestic magazines, notably Arthur’s Home Magazine (1852–87) and Lippincott’s Magazine (1868–1915), also contain discussions of both portrait studio and medical practices that speak to the social values and experiences of their predominantly urban, white, middle-class readers.

As a book focused primarily on figurative relationships between photography and medicine expressed in written texts, Doctored reproduces an admittedly unusual collection of images; many of these belong to the category of commercial visual culture and some fall outside the traditional category of “photography.” It reads, for instance, the engraved illustrations that fill Philadelphia’s photographic literature in the second half of the nineteenth century as important evidence of the material culture of the city’s early portrait studios. While such images, like the written descriptions that accompany them, can provide valuable information about the physical objects and experiences in photographic studios, they are, of course, themselves complex texts that require interpretation. When published in the context of a photographic journal or textbook, an engraving of an operating room or darkroom can express an idealized vision of the work and bodies it depicts and hence compete with other, at times satirical representations of studio interiors that appeared in the popular press. Studying the space of the early portrait studio thus requires a critical navigation of re-presentations that can only ever produce a highly mediated “reality” of that environment.

Although it is attentive to “photographic culture” in a variety of forms and contexts, Doctored remains fundamentally interested in the enormous number of photographic portraits produced by Philadelphia studios between roughly 1860 and 1890. In making such a claim I do not intend to mislead the reader, who might expect to find copious reproductions and formal analyses of these portraits in a book where relatively few are to be found. Rather, I mean to suggest that all of the written and visual texts I examine tell us something about what studio portraits could mean to photographers and sitters who persistently compared studio portraiture and medicine. The albumen portraits that do appear in the book, moreover, are interpreted as the visual products of such modeling and metaphor making. And so a group portrait of the National Photographic Association’s founding members speaks to the medical roots of photographers’ professional self-image, a carte de visite of a young boy held stiffly erect by a posing stand tells us about the complex surgical connotations of the photographic “operation,” and a cabinet card depicting a family of three shows us how white skin functioned in both photographic and medical discourses as a sign of good health.

Outline of the Book

Doctored begins by investigating the ways in which early portrait photographers, concerned about their precarious social status, turned to American medicine as a professional and epistemological model beginning in the 1860s. Chapter 1 shows how this model informed the structure of photographers’ trade literature, the aims and practices of their first national union, and proposals for schools to train young men to enter the burgeoning profession. By exploring the specifically medical roots of photographers’ institutionalization strategies, this chapter emphasizes the centrality of science and the field of the body to establishing portrait photography’s cultural identity and authority. At the same time, it acknowledges that photography’s relationship to medicine was a matter of much debate through the 1880s, as the leaders of the Philadelphia photographic community vigorously explored its nature and limits.

This discussion sets the stage for an analysis of the medical foundations of photographers’ material practices in the portrait studio. Chapter 2 looks at the many resemblances between photography and “operative medicine” that took shape around the time of the Civil War. Perceptions of these similarities resulted in part from the bodily discomfort studio patrons associated with photographic “operations.” While sitters often likened the posing stand to dental instruments, in expressing apprehension about their painful effects on the body and threats to bourgeois respectability, photographers portrayed their operations as relying upon a diagnostic way of seeing that was associated with surgical practices of the period. Adopting the guise of surgeons, photographers imagined that they could penetrate deeply into the body, distinguishing the normal from the pathological, with the aim of physically and socially remaking their subjects. Additional analogies between photography and anesthesia, which were as much assertions of photographers’ professional character as comments on the physical experience of posing in the portrait studio, rationalized photographers’ power to radically reconstruct the “face” of the American public.

The remainder of the book examines how photographers adopted the values of public health reform in an effort to further their professionalization and contribute to the postbellum project of restoring national fitness. Chapter 3 considers how portrait photography’s reliance upon light lent the technology significant therapeutic potential at a time when many middle-class Philadelphians believed that bathing in a combination of blue light and sunlight could cure everything from hair loss to nervousness. At the height of the blue-glass craze, which coincided with the end of Reconstruction, the standard use of blue glazing in photographers’ skylights motivated the idea that a visit to the portrait studio could be a similarly healthful and restorative experience, one that potentially rid sitters’ bodies of any deviations from the ideal of whiteness. The chapter’s discussion of phototherapeutics, both in and out of the studio, is fundamentally concerned with perceptions of race as an unstable social category in the decades after the war. Technologies of light were ravenously consumed at the same time that they were satirized and discredited in this period, I argue, because they promised a mass “whitening” of the nation’s urban population.

Unlike the operation room (or glass house) of the commercial portrait studio, which was generally modeled on an ideal domestic interior, the photographic laboratory was widely viewed as a bustling, unhealthy space of labor and production. To ensure its physical and social well-being, the commercial photographic community had to carefully manage the interactions among the chemical operations performed in that environment, the toxic substances employed, and the bodies that occupied the portrait studio. Chapter 4 explores how these perceptions of the photographic laboratory took shape after the war, specifically in relation to measures to sanitize American cities and treat urban epidemics. Not only were photographers trained by their trade literature to perform emergency and preventive medicine in response to the perilous effects of darkroom work, but, as Snelling’s “Doctor Photo” reminds us, those texts also ironically transformed the serious health risks associated with photographic chemistry into an occasion for praising the unparalleled healing powers of photographers and their materials. In these ways, photographers could be seen as gentlemen of science and major actors in public health reform throughout the postbellum period, while photography could function as a technology whose unmediated access to the body allowed it to cure the seemingly incurable.

The final chapter enlarges the book’s historical and geographical focus to discuss the recent reemergence of medical models and metaphors in digital photographic discourse. Since the 1980s, digital camera technologies and image manipulation software have revolutionized the art of “doctoring” photographs for fine artists, commercial operators, and amateur snapshooters. These groups, moreover, have frequently portrayed themselves as “photo doctors” and “pixel surgeons” who perform a set of virtual medical procedures on the bodies of their subjects. Taking these representations as its subject, chapter 5 reframes the discussion of Philadelphia’s commercial photographic community in Doctored as a prehistory of the medicalization of digital photography in our contemporary “makeover culture,” revealing how “old” cultural practices continue to shape conceptions of “new” media in the twenty-first century.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.