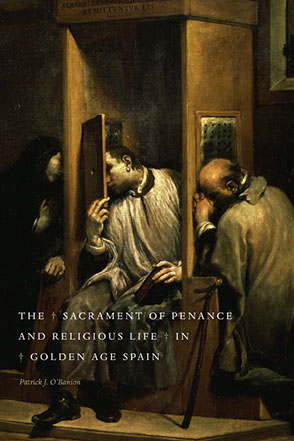

The Sacrament of Penance and Religious Life in Golden Age Spain

Patrick J. O'Banion

$78.95 | Hardcover Edition

ISBN: 978-0-271-05899-3

$39.95 | Paperback Edition

ISBN: 978-0-271-05900-6

DOI: 10.5325/j.ctt7v5ct

Available as an e-book

248 pages

6" × 9"

5 b&w illustrations/1 map2012

The Sacrament of Penance and Religious Life in Golden Age Spain

Patrick J. O'Banion

“Patrick O'Banion's work addresses the most understudied—and most misunderstood—of all the sacraments: penance. It resists older scholarly models that discuss the sacrament of penance exclusively in terms of power and oppression and instead seeks to examine the active participation of the faithful. Therefore, while O'Banion looks specifically at early modern Spain as a case study for examining the role that the sacrament played in the spiritual lives of ordinary people, his conclusions have broader implications for understanding devotion and practice in the Catholic world.”—Erin Rowe, University of Virginia

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

The Sacrament of Penance and Religious Life in Golden Age Spain explores the practice of sacramental confession in Spain between roughly 1500 and 1700. One of the most significant points of contact between the laity and ecclesiastical hierarchy, confession lay at the heart of attempts to bring religious reformation to bear upon the lives of early modern Spaniards. Rigid episcopal legislation, royal decrees, and a barrage of prescriptive literature lead many scholars to construct the sacrament fundamentally as an instrument of social control foisted upon powerless laypeople. Drawing upon a wide range of early printed and archival materials, this book considers confession as both a top-down and a bottom-up phenomenon. Rather than relying solely upon prescriptive and didactic literature, it considers evidence that describes how the people of early modern Spain experienced confession, offering a rich portrayal of a critical and remarkably popular component of early modern religiosity.“Patrick O'Banion's work addresses the most understudied—and most misunderstood—of all the sacraments: penance. It resists older scholarly models that discuss the sacrament of penance exclusively in terms of power and oppression and instead seeks to examine the active participation of the faithful. Therefore, while O'Banion looks specifically at early modern Spain as a case study for examining the role that the sacrament played in the spiritual lives of ordinary people, his conclusions have broader implications for understanding devotion and practice in the Catholic world.”—Erin Rowe, University of Virginia

“Safeguarded by a seal of silence, the sacrament of penance will always maintain its secrets. Patrick O’Banion’s thoughtful and readable study, however, provides numerous insights into this practice and its uses by lay Catholics in early modern Spain. His careful reading of a wide variety of sources, notably Inquisition records, reveals the manifold ways in which Spaniards embraced the sacrament but also navigated their way through a complex, dynamic, and surprisingly flexible confessional culture. This impressive book will be of great interest to scholars of religious change, state building, and the construction of individual and collective identities in the early modern Catholic world.”—Jodi Bilinkoff, University of North Carolina at Greensboro“O’Banion’s thoughtful study is on balance a skillfully executed and welcome addition to the growing literature on religious practice in early modern Spain.”—David Coleman, American Historical Review“The fourteenth-century Bohemian priest John of Nepomuk was allegedly martyred for his refusal to break the seal of the confessional. Even today U.S. law recognizes the right of a priest to withhold evidence confided to him in the sacrament of confession. How then is it possible for historians to reconstruct the experience of sacramental confession for early modern Spaniards? Patrick J. O’Banion draws on manuals for confessors and penitents, synodal statutes, and Inquisition records to give a glimpse of confession’s function and practice in The Sacrament of Penance and Religious Life in Golden Age Spain. . . . O’Banion has succeeded in explicating a vital part of religious life in early modern Spain.”—Amy Nelson Burnett, Church History“Confronting the problem of gaining access to the secrets passed between priest and penitent, Patrick O’Banion turns first to the treatises and manuals produced by theologians and practitioner clerics. We know from ample study in recent decades that proscriptive texts have much to tell us about the thought worlds of clerics. They also illustrate those clerics’ beliefs about what constituted proper thought and action on the part of penitents. O’Banion goes beyond a textbook review of the how-to books by taking a special interest in what they reveal about power relations between confessors and penitents. From text to text, for example, what writers considered normative shows considerable variety. In this finding is revealed a core two-part truth: ‘penitents did not necessarily have the same objectives as the church’ and, thus, ‘local confessors were forced to mediate between institution and individual.’ Much about the sacrament was negotiable.”—Michael Vargas, Bulletin of Spanish StudiesPatrick J. O’Banion is Assistant Professor of History at Lindenwood University.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations and Conventions

Introduction

1 How to Be a Counter-Reformation Confessor

2 How to Behave in Confession

3 Regulating the Easter Duty

4 Confession on Crusade

5 Confession at the Intersections of Society

6 Confession and the Newly Converted

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

There is a corresponding increase both in the priest’s power . . . and of his knowledge. . . . The power and knowledge of the priest and church are caught up in a mechanism that forms around confession as the central element of penance.

—Michel Foucault

During the summer of 1581, the inhabitants of Los Sauces on the island of La Palma in the Canaries alerted the Inquisition that one Pantaleón de Casanova had, for some years, shirked his annual duty to confess. The witnesses were sworn to secrecy, but perhaps Casanova got wind of trouble; on 10 September he tried to remedy the situation by confessing to a Franciscan friar on Tenerife Island. “How long has it been since you last confessed?” the friar asked. “Well,” responded the layman, “I didn’t make my annual confession this year, but usually I do, just like the Holy Mother Church commands.” Casanova described how an episcopal representative had threatened him with excommunication unless he separated from the woman with whom he was living. “Since I didn’t want to throw her out,” he told the friar, “I didn’t confess. Instead, I left Los Sauces.” Now he was trying to “leave for Spain and get off this island.”

Casanova found the Holy Office as unimpressed by his attempts to avoid prosecution as it was unhappy about his repeated failures to confess. It considered him “suspect of heresy for having remained aloof from the sacraments of penance and the Eucharist for so long.” Many of his neighbors testified against Casanova. Not even his parish priest (cura) could offer protection; he had never confessed the defendant.

The sacrament of penance, one of the seven sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church, which served as conduits of grace between God and the faithful, had its roots in sinful humanity’s need to be reconciled with a holy deity. That need for forgiveness went beyond merely addressing the actual sins that people committed on a daily basis, for everyone was born separated from God as a consequence of Adam’s rebellion. This state of original sin necessitated the cleansing waters of baptism, which infused grace and made the recipient a beneficiary of Christ’s meritorious sacrifice on the cross. Baptism cleansed sinners of the guilt (culpa) they incurred from original sin and satisfied the punishment (poena) they deserved. It also removed the stain of guilt and paid the penalty for any actual sins committed before baptism. It granted entry to the church and made the recipient a child and friend of God. But the temptations of the world, the flesh, and the devil frequently lured Christians from the righteous path. Sins committed after baptism not only incurred new guilt but demanded additional punishment.

Yet, according to the Roman church, not all sins were equal. Some were venial and could be expiated simply by confessing them to God and making restitution. They did not demand priestly intercession in the sacrament of penance. But more serious sins, which killed the grace infused at baptism, were mortal; those who committed them became “children of wrath and enemies of God.” The culpa for such offenses could only be remitted sacramentally. While the early church had allowed penance only once in a lifetime, during the Middle Ages it became possible to receive the sacrament multiple times. Indeed, in the famous decree Omnis utriusque sexus the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) had obliged all Christians who had reached the age of accountability (about age seven) to confess their mortal sins to their own priest (proprio sacerdoti, typically understood to mean their parish priest) at least once a year before receiving the Eucharist. When they did so, penitents needed more than just a desire to avoid suffering eternal punishment, or attrition. While fear of hellfire might draw the sinner toward confession, the sacrament itself was necessary to transform attrition into contrition, sorrow for having offended God combined with the intention of not persisting in the sin.

In most cases, the priest subsequently either absolved the sinner of guilt or pronounced the confessant excommunicate, but some serious offenses, known as reserved sins, were passed on to higher ecclesiastical officials. The judicial power by which priests declared the forgiveness or condemnation of sinners was rooted in the power of binding and loosing given by Jesus to Peter in Matthew 16:19, according to the Roman church’s reading of that passage. As Peter’s successor, the pope wielded authority on earth to bind and loose spiritually by absolving or excommunicating. He delegated this power to bishops and priests, who meted out God’s justice and mercy in the forum of confession in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

While culpa could be absolved, sinful actions still required restitution in the form of poena. Although offenses committed against a supremely exalted and holy God deserved eternal punishment, the atoning sacrifice of Christ had satisfied divine justice on their behalf. Yet the damages caused by both mortal and venial sins had to be set right in the here and now as well as in eternity, and this meant addressing the demands of temporal punishment. It was for this reason that confessors assigned penances or acts of satisfaction (opera satisfactionis). These might be horizontal communal acts, like restoring stolen goods or reconciling with a neighbor. They might be directed vertically through the saying of prayers such as the Our Father and Hail Mary or in the completion of pilgrimages and fasts. Or they might combine the horizontal and the vertical by, for example, obliging the sinner to attend public masses while holding lighted tapers or wearing penitential garb. Through these opera satisfactionis sinners endured punishment for their sins.

Yet it often happened that believers, whose sins had been absolved in confession, died before making full restitution of the temporal punishments those sins demanded, by failing to complete acts of satisfaction or completing them imperfectly. Thus the church came to understand the need for a doctrine of purgatory. Sinners who had been restored to good fellowship with God but who had not yet been completely purged of the remnants of sin spent time in this antechamber to heaven. Only Christians entered purgatory, and everyone in purgatory eventually went to heaven, but only after making full restitution for sins and undergoing a process of refinement.

In premodern Europe, the boundaries between the here and the hereafter were often permeable, and so it was possible for those living on earth to aid their loved ones in purgatory, just as it was possible for the heavenly host to assist earthly or purgatorial pilgrims. By endowing masses, praying for the intercession of saints, and gaining indulgences for the dead, friends and relatives could speed the souls of beloved sinners on their way to heaven. Those who did so hoped that, when they died, others would act in a similar fashion on their behalf.

We can speak, then, not merely of a sacrament of penance, which was necessary for getting into heaven, but of a great penitential economy that suffused culture and was foundational to religious life. This system underwent dramatic challenges during the early modern period, especially from Martin Luther’s rapidly spreading reform movement, which denied the confession’s sacramental character, viewed acts of satisfaction as works righteousness, and attacked the doctrines of indulgences and purgatory. But as the story of Pantaleón de Casanova suggests, even in stoutly Roman Catholic Spain, people had variegated experiences with the sacrament of penance.

To be sure, Casanova made a mess of his confessional obligations, but his story emphasizes the complex reality of the sacrament in an early modern context; it could put confessants in a real bind. In Casanova’s case, in order to receive absolution, he would have had to put his mistress out. Failure to do so meant excommunication, spiritual (and often social) separation from the community of believers. The sacrament thus engendered moral reform by exposing sinful activity—here, illicit sexuality and interaction with a potential heretic, for his lover was a descendant of converted Muslims, a morisca. Community life also exerted strong influence upon the confessional experience. Family, friends, and neighbors often provided ill-treated penitents with invaluable support, but here the inhabitants of Los Sauces turned against one of their own. Finally, the episode gestures at the defendant’s (unsuccessful) attempt to circumvent the system of penitential regulation by confessing outside his parish and trying to get “off this island.”

In early modern Spain, the sacrament proved trying in other ways as well. Many felt conflicted about revealing deeply guarded secrets to fallible confessors, particularly when they played an active role in a community’s social life. Although priests were bound to confidentiality by the seal of confession, a priest might (maliciously or inadvertently) let slip a few words that could damage a penitent’s reputation. Especially for women, confession entailed the possibility of sexual solicitation and subsequent public scandal. To heretics and even to the misinformed, the sacrament posed a threat because confessors used the encounter to determine parishioners’ orthodoxy. Many early modern churchmen came to view confession as the linchpin in a program to reform the religious lives of laypeople, since priests used the encounter to examine, catechize, and correct. Ecclesiastical superiors ordered confessors to deny absolution to penitents who could not recite the appropriate prayers or who had not sufficiently scoured their conscience in preparation for the sacrament. For the numerous reserved sins, among them heresy, public blasphemy, and sexual solicitation in the confessional, the church obliged priests to remit penitents to the pope, the bishop, or the Holy Office.

Confessants had their own agendas, of course. Most saw confession as a necessary stop on the road to salvation and so they participated in it. Some formed deep spiritual friendships with confessors. As the early modern church pressed penitents to meet their confessional obligations and ratcheted up expectations about what constituted a complete and fruitful sacramental encounter, most laypeople in Spain responded by meeting those expectations. They did a better job of completing their mandatory annual confession and often participated in the sacrament at other times during the year as well. Most memorized the prayers of the church and the Ten Commandments and learned how to make the sign of the cross properly, when to kneel, and how to demonstrate proper humility in the confessional. This did not mean, however, that confessants became merely passive participants in the encounter. Laypeople knew what scandals could arise from confessing embarrassing sins or sins that demanded public penance. They valued their good standing in the community and vigorously guarded their honor. If they rarely refused outright to engage in the sacrament, they often took part warily. Some deceived their priests, leaving embarrassing or entangling sins undisclosed, but confessants knew that doing so tempted the justice and mercy of God.

Such inconveniences make it all the more remarkable that during the early modern period the sacrament of penance became more attractive to laypeople. In fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Spain, the sacrament lacked both rigor and force. While the idea of penitence was deeply embedded in religious culture, auricular confession was a marginal component of religious life. Yet in the decades that followed it moved to the center, becoming a prominent component of lay devotion. In terms of popularity, proliferation, emphasis, and theological, material, and liturgical development, Spain’s siglo de oro proved to be a golden age for confession.

This gold, however, contained a certain quantity of dross, for during this period Spanish confessional practice, while in theory well regulated, rarely adhered to the letter of the law. After the Council of Trent (1545–63), the kings of Spain urged bishops and archbishops across the Iberian Peninsula to convene provincial councils and episcopal synods, which formulated intricate programs for enforcing penitential compliance at the parish level. All baptized Christians were to confess annually to their parish priest, normally at Lent before receiving the Eucharist—the Easter duty. If the number of penitents proved overwhelming, the cura could draft other episcopally licensed confessors to meet the demand. Curas were to keep registers (matrículas or padrónes) in which they recorded which parishioners had fulfilled their paschal obligations. The names of those who failed to do so were read aloud at Mass and posted in their church for all to see. Parish priests were to pronounce the obstinate excommunicate and annually forward matrículas to the bishop. This would make apparent whether the local minister had been shepherding his flock conscientiously and open the way for bishops to pursue recalcitrant sheep with more severe measures. Prolonged refusal to confess would result in a denunciation to the Holy Office on charges of heresy (for obstinately disobeying the precepts of the church), an inquisitorial trial, and, at least theoretically, relaxation to the secular arm and death.

This system was clear and rigid. It recalls Keith Thomas’s description of the sacrament: “The personal confession and interrogation of every single layman was potentially an altogether more comprehensive system of social discipline than the isolated prosecution of relatively notorious offenders.” Likewise, confession’s dependence upon the communication of information to authority figures conjures Michel Foucault’s depiction of the relationship between knowledge and power. Foucault suggests that confessors and their ecclesiastical superiors wielded power because they had knowledge; this conjunction of knowledge and power facilitated social discipline. Thomas Tentler has similarly argued, “Knowledge supports the authority of the priest. He is in control because he has the requisite information to conduct the confession with confidence.”

The confessional may have had great disciplinary potential, and sometimes it afforded a Foucauldian combination of knowledge and power that enabled authorities to exercise control over confessants. The parish reality, however, rarely allowed confession such a robust function. This conclusion runs counter to expectations, particularly since Spain has so often been viewed as the acme of oppressive religiosity, rife with inquisitors, their lay cronies (familiares), seminary-trained priests, and the powerful arm of the secular state using religion to perpetuate entrenched authority. Nevertheless, the ramshackle settlements that grew up at the local level bore only a passing resemblance to the plans devised in the corridors of power. Priests rarely refused to comply with the demands of their superiors, and laypeople rarely viewed themselves as religious renegades, but the parish proved rather untidy and far too complex a context for synodal decrees to address adequately.

Still, Foucault was right to say that knowledge implied power, and the early modern confessional was a rich fount of knowledge. The power that flowed from it, however, did not flow in one direction, for the sacrament was as much a system of inclusion as of exclusion, as much an affair of the laity as of the clergy, as much a means by which laypeople were empowered as a method by which the powerful remained in control. In confession, power was negotiated, not forfeited.

This notion of negotiation has proved to be a handy tool for focusing attention on the dialogical nature of sacramental encounters. Priests never simply imposed Tridentine norms on confession at the local level, because no clear, authoritative Tridentine voice existed to tell a confessor how to interact with the bewildering diversity of penitents with whom he came into contact. This was not for lack of trying; theologians formulated a vast array of instructions, guidebooks, and practical advice for confessing early modern Spaniards. Ultimately, however, too broad a range of (often contradictory) decrees and advice existed. In the midst of this ambiguity, the confessor and, significantly, his confessants found it expedient to interpret and apply those prescriptions according to their best judgment. This flexibility in the relationship between dominant (clerical) and subordinate (lay) groups allowed confession to maintain popular legitimacy into the modern era.

There is another sense in which negotiation is a useful concept for studying penitential activity. Confessants negotiated the sacrament by navigating, often with practiced skill, the loopholes and gray areas in the system of confessional regulation formulated at the episcopal level. Rather than alienating people, this bureaucratization actually enabled them to engage that sacrament in new and creative ways. It became easier to circumvent specific priests, avoid entanglements with high ecclesiastical authorities, fulfill sacramental obligations, and redress grievances.

Councils could decree and bishops could legislate; kings and queens could demand obedience to church and state, but when a sinner knelt before a confessor in the confessional, they entered into a dialogue. The personalities, theological leanings, and social status of the priest and penitent, their feelings toward each other, their lineage, gender, ethnicity, and reputation, their familiarity with each other—all of these variables affected that conversation, but none of them fully determined its course. In most cases, the possibility existed that, if both parties played their parts well, the end would be a mutually satisfying process of reconciliation in which sins were confessed and absolution granted.

Historians and the History of Confession

Historians find themselves on much firmer ground for studying these complicated interactions than they were even a generation ago. A bumper crop of research on Roman Catholic Europe and its non-European mission fields has grown up alongside studies on Protestant and Orthodox regions and cross-confessional analyses. In meeting the challenge posed by John Bossy in 1975 to infuse real life into a “bloodless universe” of penitential summae and theological debate, scholars have focused the historical lens on how individuals, especially laypeople, experienced the sacrament in relatively delimited times and places.

Rather than read prescriptive treatises and decrees alone, historians have turned up new sources for the study of confession—saints’ lives, visitation reports, trial transcripts, parish records, written confessions, marginalia, wills, and such artifacts of material culture as confessionals, religious art, and church architecture. This has revealed an incredibly intricate world. The tortuous theological debates about sin and the forgiveness of sin became heated during the early modern period, but those who sought forgiveness in confession and those who administered the sacrament found themselves embroiled in controversies and debates every bit as intense, and often much more personal. While confession rarely led to bloodshed, it frequently raised blood pressures.

We have also come to realize confession’s intimate connection to other historical themes. Roman Catholic confession, for example, required that at least one of the parties involved be an ordained priest. But who were these priests, and how did they differ (or not) from their medieval predecessors? What about their relationships with the faithful whose souls they tended? These questions have led historians of confession to the topic of clerical formation, since the Council of Trent placed local clergy on the front lines of the reforming program; they became both its main targets and its chosen tools for effecting grassroots change. As the church’s local representatives, parish clergy needed a behavioral and educational reformation of their own before they could effectively reform their flocks.

Many members of the ecclesiastical hierarchy pursued this goal, even mandated its implementation, with seminary training as the preferred path to success. Did improvements actually occur? Some historians have argued that local priests underwent a process of professionalization during the early modern era. As a result, they became the unwanted purveyors—unwanted by the laity, at least—of an alien system of baroque Tridentine morality among marginally Christianized European laypeople. This suggests that while priests may have labored to implement reforms, the laity did not necessarily approve of their efforts. Andrew Barnes put it this way: “In the end, the reform of the parochial clergy pushed the rural laity further away from the church.”

Other historians have questioned this model of clerical professionalization, emphasizing that laypeople often held on to customs and traditions in spite of reforming programs, or that they actually sought better-trained clergy, becoming an impetus for reform in their own right. Marc Forster and Allyson Poska, among others, have emphasized the laity’s ability to arrive at compromised religious settlements with local priests and, sometimes, to resist the implementation of reform altogether. Unfortunately, historians of early modern Europe still know very little about the secular clergy, and in Spain this lacuna is particularly acute. Nevertheless, to judge from the example of northern Italy, there is every reason to question the effectiveness of seminaries in forming priests along a Tridentine model until the eighteenth century.

Historians often focus on the role played by local clergy as enforcers of ecclesiastical reforming programs at the parish level, an emphasis that stems from historiographical debates about the relationship between religion, social discipline, civilizing processes, and state formation. Here, clerics become the purveyors of top-down programs, and confession itself becomes the locus wherein the church regulated moral order and enforced social discipline, a veritable instrument for the onset of modernity. Yet the compromised nature of local religious settlements and the incomplete character of early modern clerical formation bid one take great care in claiming confession as a mechanism for modernization. In fact, the local implementation of reforming programs for sacramental confession indicates that bottom-up initiatives affected practice as much as did top-down decrees.

As this suggests, another important historiographical axis for confession is the role of lay agency. Concepts of social discipline, confessionalization, and Christianization are distinct in many regards. However, historians tend to view early modern reforming programs as implemented from on high upon a passive and oppressed laity. Tentler, for example, sees the fact that “hierarchical and priestly authorities are in command” of the sacrament as an “almost truistic observation,” and he argues that medieval summae were “designed to present a coherent system in which [those authorities] can order, threaten, persuade, control.” From this vantage point, the power relations at play appear truly lopsided.

Michel Foucault, who emphasized the dialogical nature of confession, was still drawn to a top-down model. Even as states built institutions that allowed them to exercise control over subjects’ bodies, the church developed “an immense apparatus of discourse and examination, of analysis and control,” wherein “all, or almost all, of an individual’s life, thought, and action” passed through the confessional to be seen and heard by the priest. To be sure, Foucault hardly imagined these interactions between laypeople and clerics occurring in a vacuum. They happened in a hierarchically ordered society in which religious authority entailed power that could be wielded in various ways. Confession, then, became “a ritual that unfolds within a power relationship.” The recipient of the confession, Foucault explained, became more than a simple interlocutor; he became “the authority who requires the confession, prescribes and appreciates it, and intervenes in order to judge, punish, forgive, console, and reconcile.”

This insight, certainly an important part of the larger picture, deserves careful reflection. Foucault tied these developments to the program advanced at Trent and modeled for implementation by Archbishop Carlo Borromeo in Milan (r. 1564–84). However, many scholars have emphasized that reforming programs promulgated at the highest levels always became negotiated phenomena when brought into contact with local communities. In France, for example, while a rhetoric of rigorous reform dominated discourse about clerical behavior, the parish reality failed to correspond: “Once they were left alone with their flocks, the clergy naturally responded with a series of makeshift compromises.” Likewise, the power relations at work between confessors and confessants demand cautious and patient analysis. Confessants, particularly devout ones, exercised real influence, and priests often needed the penitential exchange as much as those they confessed. All of this suggests that perhaps confessors were not the only ones judging, punishing, forgiving, consoling, and reconciling.

Spaniards participated in the sacrament of penance from their youth. They discussed it in church, on the streets, and at home. They understood, with a perspective born of experience and necessity, the ins and outs of confession. They knew how to use the elaborate top-down system of confessional regulation formulated at the episcopal level to their advantage. To be sure, sacramental confession typically operated in the midst of a hierarchical structure, with the priest exercising authority over the penitent. At times, confessants experienced that structure as oppressive or wrong. However, this did not mitigate the vast array of loopholes and tricks that laypeople used, before, during, and after the encounter, to minimize potential dangers and disadvantages.

The oppressive use of religious power tended (as it still does) to fall most heavily upon weak and marginalized members of society. Just as nobles seldom faced the inquisitorial tribunal for blasphemy, so well-born women rarely became targets for priests who sexually solicited their penitents. Confession thus intersects the field of gender and minority studies and questions about how the early modern reformations affected these groups. Certainly, on the issue of women, opinions have been divided in recent decades. Of late, however, a number of authors who have considered the religious and confessional lives of women have fashioned answers that tease out the subtle interplay of religious power dynamics in early modern society. Increasingly, historians have come to recognize that, even when disenfranchised from official avenues of power, early modern women knew how to assert themselves and found their own ways of exercising influence. The same held true for their penitential activities. In fact, many women found confession an important part of their identity.

This is not to say that discrimination, gender-based or otherwise, did not exist. For example, Old Christians (i.e., Spaniards who could claim to be free of Jewish or Muslim blood) often treated the marginalized differently from how they treated one another. Converted Jews (judeoconversos), gypsies, and moriscos frequently experienced prejudicial treatment and harsh punishments for misdeeds, both real and perceived. However, these groups also found ways to subvert and overcome their marginalization by colluding with local priests and seigneurs, burying their pasts, using penitential bureaucracy to their advantage, and shunning the confines of the parish. Although they did not always succeed, the marginalized deployed strategies and wielded power in the search for a modus vivendi.

Debates about insiders and outsiders highlight the communal nature of early modern society. Did confession support or erode that communalism? Some have taken the increasing prominence of confession as emblematic of a more interiorized and individualistic (read: modern) religiosity. In the 1980s John Bossy argued that early modern Roman Catholicism saw confession transformed from a highly communal practice focused on rooting out social discord into an institution focused on penitents’ offenses against God. In Jean Delumeau’s opinion, this interiorization of moral rigor produced “the most powerful mass imposition of guilt in history.” The turn toward self-discipline and introspection thus heralded the modern self. In a similar vein, the literary critic Peter Brooks has suggested that “what we are today—the entire conception of the self, its relation to its interiority and to others—is largely tributary of the [Lenten] confessional requirement.”

Focusing on Roman Catholic Bavaria, David Myers has reconsidered this model. Myers agrees that alterations in setting, ritual, and performance made the sacrament “more conducive to private counsel and interior discipline.” However, rather than a guilt complex, the result was “chronic uncertainty” about the sinfulness of actions. This in turn led increasingly scrupulous confessants to listen with ever-greater fervor to the authoritative voices of the church. Clerical counsel became more, not less, important.

Wietse de Boer offers a more direct attack against the interiority thesis in his study of Borromeo’s Counter-Reformation Milan by emphasizing the ongoing communal nature of confession. Both Foucault and the literary critic Matthew Senior saw Borromeo’s development of the confessional box as especially expressive of the modern individualistic self. It resulted in what Senior has called “‘ghostly’ conversation” and established a barrier between “the Imaginary, face-to-face encounter between priest and penitent and reduced the encounter to the Symbolic.” Instead of confessing intimate details to a real person, penitents confessed to a disembodied ear devoid of personality or identity. However, de Boer suggests that Milanese reform of confession did not disrupt the sacrament’s communal nature. Borromeo developed the confessional not to afford confessants privacy but to separate male priests from female penitents. Furthermore, once imposed, the laity were often slow to accept the use of confessionals. Borromeo’s focus on imposing moral order through the confessional apparatus meant that the sacrament held striking communal and public implications.

Likewise, Jodi Bilinkoff’s study of devout female confessants, and the ways in which their confessional lives became a matter of public record, challenges the notion that early modern confessional behavior served as a conduit for or an expression of a modern, individualistic religious ethos. The seal of confession forbade priests to disclose secrets while the penitent lived, but after the death of holy confessants spiritual directors often published vitae, which described confessional encounters in detail. These works circulated widely and became important models for early modern Roman Catholic readers, thus drawing the private encounter into the public sphere.

In Spain, confessional practice also continued to exhibit strong communal elements. The enclosed confessional did not become an important piece of architecture in most churches until well into the seventeenth century. Moreover, as in Milan, when it gained ground, the confessional’s main purpose was to impose a physical barrier between female penitents and their priests and to do so in a publicly visible way. Although confession was private in certain regards, that privacy belies a series of communal interactions that affected how priests and penitents engaged one another. Family ties, social connections, and patronage networks had deep and sometimes determinative consequences for confessional behavior. However, some developments ran contrary to this ongoing communalism. The rising population and availability of regular priests gave laypeople easier access to confessors whom they did not know and who did not know them. This trend did more to increase expectations about anonymity than the imposition of the confessional. It is ultimately more indicative of modern individualism in the early modern period than is scrupulosity among confessants.

Scope, Sources, and Methodology

The chronological scope of this study spans the two centuries between 1500 and 1700. While such round numbers are admittedly somewhat arbitrary, they represent meaningful boundaries. Archival documents and early printed books that prove useful in studying early modern Spanish confessional practice multiplied around the mid-sixteenth century. After 1700, however, while printed sources remained abundant, inquisitorial activities and the archival records they produced tapered off. The two centuries that we focus on here thus provide a rare, detailed glimpse of confessional practice.

Moreover, much evidence suggests that from the mid-sixteenth century confession became more important for many Roman Catholics. In 1500 it constituted an infrequent and marginal component of devotional life, which most people performed no more than annually. By the late seventeenth century it had become a remarkably popular aspect of lay piety among Spaniards, with deep ties to communal life and religious identity. During those two centuries, Spanish presses flooded the market with vernacular confessional manuals, the Jesuits took up residence in Spain and popularized frequent confession, parish churches introduced confessionals, and bishops developed elaborate schemes for regulating sacramental behavior. Between 1500 and 1700, early modern confessional practice did more than just develop; it underwent a process of maturation.

It is precisely at this point, however, that historians find themselves prone to commit the sin of despair. For despite confession’s importance during this period, the secrecy that surrounded the encounter makes it notoriously difficult to study. Consequently, historians often rely upon prescriptive sources that describe confession from an official point of view. These works—confessional manuals, ecclesiastical decrees, devotional works, even hagiographical lives—illustrate what the church wanted confession to look like. But if the goal is to describe confessional practice, then the descriptions they offer are highly problematic. Relying primarily upon prescriptive literature assumes too much about the correspondence between the ideal and the local reality. They were not the same.

This is not to say that prescriptive literature has nothing to offer. On the contrary, it is indispensable for understanding confession, since it describes how the church sought to use the sacrament as a reforming apparatus. Close readings can also highlight the variety of distinct, and often contradictory, approaches to confessional practice. Ironically, as we shall see, this abundance of advice undermined episcopal attempts to use confession, especially the mandatory Lenten confession, as a means of regulating and reforming laypeople.

Fortunately, sources of a more descriptive nature also exist. For Spain, rich inquisitorial archives offer up precious glimpses of confessional life, but at a cost. Trial records (procesos) are challenging sources. Some historians have cast doubt upon the reliability of statements made under torture and suggested that educated, legally minded inquisitors and scribes often imposed their worldview on the proceedings. William Christian has suggested that “building a picture of rural Catholicism from [the inquisitorial] archives would be like trying to get a sense of everyday American political life from FBI files.”

While these criticisms have some merit, procesos offer a great deal of useful information. Proceedings against lesser offenses (blasphemy, scandalous words, and lewdness) and against priests who made sexual advances toward their penitents (cases of sexual solicitation in the confessional), neither of which entailed torture, have proved particularly useful for this study. Certainly, inquisitors had expectations about the nature of heresy and led their witnesses. Our concern, however, is not the relationship between inquisitorial justice and the reality of guilt but rather aspects of confessional behavior in which the judicial proceedings were relatively uninterested.

The key to using procesos to study sacramental practice lies in seeing that inquisitorial scribes recorded a great deal more than just confessions and verdicts. They also preserved rich supplementary descriptions of daily life. Although the flotsam and jetsam of courtroom testimony are, to be sure, mediated through inquisitorial authorities, they nevertheless communicate a remarkably gritty sense of the material world in which confessions happened and sometimes provide insight into the emotional or mental world of participants as well. Occasionally, scribes recorded penitential behavior because it had a direct bearing upon the trial, but usually such descriptions come as offhand remarks and incidental details of little direct significance to the judicial proceedings—where a confessional was located, what it looked like, what sins were confessed, the order of the ritual, the identity of the officiating priest, and so forth.

Furthermore, by the mid-sixteenth century, procedure obliged inquisitors to question all defendants about their sacramental activities, even when this had no bearing on the trial. Did they confess and commune? When? Where? And with whom? In turn, witnesses and neighbors who could speak about the religious activities or reputation of the accused might confirm or contradict the original report. Even if evidence could be twisted or misremembered, such details still express early modern Spaniards’ assumptions about good and bad penitential behavior.

To put it another way, the verdicts pronounced by inquisitors are often less useful than the descriptions of penitential activities, opinions of confessants and confessors, and expectations about the sacrament that witnesses provided. In a case of sexual solicitation, for example, the most interesting bits (for our purposes, at least) often have less to do with the solicitation than the description offered of the encounter. Where was the sacrament administered? How did the confessant choose her confessor? What did she expect to happen? What did she do when matters took a turn for the worse? Did she continue confessing with the priest in spite of the offense? Such information proves invaluable for studying confessional practice. Few early modern people left autobiographical accounts or otherwise indicated what they thought about the religious activities in which they engaged; historians must look elsewhere if they want to catch sight of the elusive common folk in the confessional box.

Procesos are complicated sources, to be read carefully, but the rich insights they offer into early modern religious life validate the effort. The sheer number of documents available—thousands upon thousands of folio pages—provides a remarkably robust picture of confessional practice. A careful balance of the insights and limitations offered by descriptive and prescriptive sources illuminates the process of religious transformation during the era of the reformations and brings into sharp relief the complexities faced by ecclesiastical leaders who sought to implement reforming programs at the local level.

In the pages that follow, we turn in chapter 1 to the realm of prescriptive literature and ask how ecclesiastical authorities and theological discourse attempted to construct confession and the role of the confessor, and how those ideas were communicated to priests and laypeople. Here we focus on printed manuals of confession. These works often exhibited a remarkable pastoral emphasis and played an important role in the church’s attempt to reform the religious lives of the people. Yet authorship often skewed prescriptive discourse about the sacrament. Members of religious orders, bishops, and local priests offered differing assessments of proper confessional practice, constructing it in ways that supported their own vision of reform.

Moving from prescription to description, chapter 2 explores the sacramental experience. The changing face of the early modern ritual of confession exposes laypeople exerting influence over the sacrament. During this era, as many laypeople began to confess multiple times each year, the church focused more intensely on properly forming and imposing meaning upon sacred space. Consequently, the confessional often became contested territory where priests and penitents sparred, making judicious use of tactics, gambits, and loopholes. Usually, a declaration of absolution brought the process of reconciliation to an end, but that outcome frequently depended less upon a strict implementation of episcopally mandated norms than upon a subtle interplay of negotiation that ameliorated rigid confessional legislation.

Chapter 3 explores that interplay and the institutions that made it possible. While Spanish bishops and synods established rigorous bureaucratic systems of confessional regulation, translating them to the parish proved difficult. Episcopal decrees imposed a very particular mode of penitential behavior, but parochial enforcement was uneven. Yet the laity of Spain did not simply refuse to obey ecclesiastical pronouncements. Instead, most Old Christians used loopholes, contradictory decrees, and theological disagreements to facilitate their confessional practice. This approach allowed them to maneuver within the system and, even for the highly bureaucratized Easter duty, to assert ownership over the experience.

In chapter 4 we pursue this theme by examining the tools used by laypeople to circumvent the episcopal system meant to regulate confessional behavior, especially the bula de la cruzada, a remarkably popular indulgence. Among other benefits, it allowed bearers to confess to the cleric of their choice at Lent, whether or not he was their parish priest. It also gave confessors the power to absolve penitents of nearly all sins, even those reserved sins that would otherwise have fallen under episcopal, papal, or inquisitorial jurisdiction. The episcopal hierarchy, the religious orders, the Inquisition, and the Spanish state frequently worked at cross-purposes because they had different priorities and goals. As a consequence, institutions such as the cruzada facilitated surprising freedom in penitential practice.

Yet institutional structures were not the sole influence on confessional experience. Thus, in chapter 5, we turn to social class, economic status, and gender. Often, the wealthy and powerful received preferment, but particularly devout confessants and devoted confessors sometimes shifted that dynamic in surprising directions. Under the right circumstances, a poor, illiterate woman could wield as much influence as a king in her relationship to a spiritual director. Gift giving and personal connections mattered as well. Support networks formed by families, neighbors, and groups of women often provided important lines of defense for the redress of grievances when the confessional encounter went wrong—when a priest broke the seal of confession or in cases of sexual solicitation. However, when those networks broke down, the results could be disastrous for the individual.

The final chapter explores what happened when the dynamic of confessional negotiation that most people experienced collapsed. This occurred most frequently for marginal ethnic and religious groups. Many Spaniards believed that judeoconversos, gypsies, and moriscos abused confession. In practice, the members of these groups tended to take distinct approaches to the sacrament: most Jews ultimately embraced the sacrament, assimilating into Old Christian society over a period of generations, changing their surnames, relocating, and burying their past. Gypsies fled from confession, withdrawing from parish structures and forming itinerant societies, which successfully evaded ecclesiastical oversight and secular persecution. The case of the moriscos represents the most dramatic failure of confessional negotiation. Perceived as a military threat and obstinate in the face of Christianizing programs, some three hundred thousand baptized moriscos were expelled from Spain between 1609 and 1614.

Early modern Spain witnessed a dramatic uptick in attempts to regulate lay confessional practice. The church hierarchy did this because it believed that it knew what its sheep needed and that it could do a better job of caring for the flock of Christ than it had in the past. As was the case elsewhere in the post-Tridentine Roman Catholic world, confession became central to caring for people and disciplining them when necessary. In fact, confessional piety did increase among the laity—dramatically so—but that new confessional piety tended to pull Spaniards away from the parish and into the arms of regular orders. Different people, of course, participated in the sacrament in different ways, but many proved reluctant to confess to their parish priest for a variety of reasons, among them social status, honor, personality, devotion, gender, and ethnicity. Yet, rather than heralding a crisis between a disobedient laity and an unyielding church, the various agendas of bishops, curas, mendicants, Jesuits, monarchs, nobles, laymen, and laywomen coalesced into a ramshackle system of confessional practice. It was unwieldy, to say the least, but it proved resilient and, for many, surprisingly attractive.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.