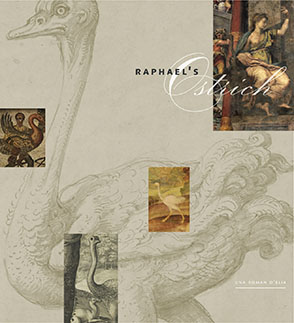

Raphael’s Ostrich

Una Roman D’Elia

“[Raphael’s Ostrich] covers a vast time-span comprising a rich collection of events and stories, some of which are novel while others are well known. But it is the unusual point of view from which these stories unfold that makes the book such a pleasure to read. Throughout, a wealth of texts and images of skillfully interwoven, making this book important for the study of the ostrich’s iconography in Italian art to 1600.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“[Raphael’s Ostrich] covers a vast time-span comprising a rich collection of events and stories, some of which are novel while others are well known. But it is the unusual point of view from which these stories unfold that makes the book such a pleasure to read. Throughout, a wealth of texts and images of skillfully interwoven, making this book important for the study of the ostrich’s iconography in Italian art to 1600.”

“Who would have thought that an ugly, earthbound bird, perceived as a hybrid monster, would play such a significant part in Renaissance art? In her fascinating and scholarly study, Una Roman D’Elia has meticulously demonstrated how and why ‘these images of hybrid creatures are both marginal and central to major cultural shifts in attitudes toward nature—at the crossroads of art, religion, myth, and natural history.’”

“Including excellent images and an ample scholarly apparatus, this is a book for those fascinated by iconography in art, in particular the iconography of the ostrich. Recommended.”

“This is a delightful, massively erudite, well-written, and well-composed treatise on an unexpected subject. It will be of interest to art historians, classicists, medievalists, literary scholars, social historians, iconographers, scholars of the classical revival, historians of science, experts in Renaissance emblems, and (above all) scholars of sixteenth-century art, especially scholars of the grotesque. It is the history of a particular bird, along with its various meanings and implications, and deals with the tension between naturalism and allegory, carrying us from ancient Egypt and Israel through Greece and Rome to the Middle Ages, the High Renaissance, and beyond.”

“Raphael's Ostrich is a learned, ambitious, and very original book. Taking as its starting point a curious detail in a painting generally credited to Raphael, it throws new light on Italian sixteenth-century ideas about artistic invention and about the ways in which works of art were meant to be understood or enjoyed by the audience for which they were made.”

Una Roman D’Elia is Associate Professor of Art History at Queen’s University.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Raphael’s Disputed Legacy

1 A Brief History of the Ostrich: Antiquity and the Middle Ages

2 The Eagle and the Ostrich: The Court of Urbino

3 Pope Leo X and Raphael’s Ostriches

4 Raphael’s Heirs

5 Farnese Ostriches and Vasari’s Raphael

6 Fortune Is an Ostrich: Discontent in the 1550s and 1560s

7 Curiosity and the Ostrich in the Counter-Reformation

8 Taming the Ostrich: Ripa and Aldrovandi Notes

Bibliography

Index

> Introduction:

<CST> Raphael’s Disputed Legacy

<1> Raphael Is Dead. Long Live Raphael!

When Raphael died suddenly in his thirties, on Good Friday in 1520, reportedly after being made feverish from too much sex, writers quickly enshrined the somewhat dissolute painter by comparing him to Christ, and artists scrambled to claim his legacy. The night of Raphael’s death was marked by prodigies—the Vatican palace split in two, just as the temple of Jerusalem had done when Christ died. Raphael requested that he be buried in the Pantheon, the ancient temple of the gods that had been rechristened as a Christian church (fig. 1). Before he chose it, this was not a prestigious place for a Christian burial, as it did not hold distinguished relics. Raphael, who had been named by Pope Leo X director of antiquities and had made many drawings of the ancient building, was surely not interested in the Christian dedication of Santa Maria ad Martyres (the name given when the building was reconsecrated). He was asking to be apotheosized in the Pantheon, the best preserved remnant of the glory of ancient Rome. After Raphael, other artists sought burial in the Pantheon to be near him, as if his body were a relic.

<insert fig. 1 about here>

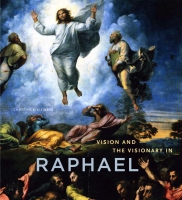

Vasari tells us that the Transfiguration, one of the last paintings Raphael completed before he died, hung above his bier and that people were consumed with grief when they compared his dead body to the living painting (fig. 2). None of the many figures in the painting is a self-portrait, so the viewers were surely comparing Raphael to the shining and triumphant Christ, raised to divine glory in the heavens while he was still alive, whose face bears a passing resemblance to the artist’s. According to Vasari, the last thing Raphael’s brush touched before his death was the face of Jesus—the divine creator of the divine creator. This painting, reinterpreted at Raphael’s death as an apotheosis of the artist, had been made as a competitive artistic statement. Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici had held a contest, in imitation of the great artistic contests of antiquity, between Michelangelo (who provided drawings for Sebastiano del Piombo) and Raphael. When the finished paintings were exhibited in Rome, Raphael was universally acclaimed the victor. Vasari tells us that Raphael continually worked on the painting “with his own hand” and so brought the picture to “final perfection.” The painting was, according to all of the artists, “the most celebrated, the most beautiful, the most divine.”

<insert fig. 2 about here>

From the seventeenth century until well into the twentieth, the Transfiguration was hailed as Raphael’s greatest work. It seems particularly perverse that even as the public fawned over the “Greatest Picture in the World,” art historians deemed half of this painting to be the work of someone else, Raphael’s chief pupil, Giulio Romano. Giulio and others surely had a hand in painting the minor parts of this large painting, as was standard practice, particularly in Raphael’s large and efficient shop. But nineteenth-century art historians regarded the whole bottom section of the picture as entirely Giulio’s. The upper part, with the softly glowing Christ floating in ethereal gentleness, was generally recognized to be the work of Raphael, but the lower section, with its discordant leaps between light and darkness and strangely twisted figures, had to be painted by someone else, surely not the luminous and harmonious Raphael of the Madonna paintings and the School of Athens. Art historians now recognize the whole as Raphael’s invention and largely his execution and see the contrasting upper and lower parts of the picture as creating an animating tension between the heavenly revelation of the divine and the earthly apostles’ frustrated attempts to exorcise a possessed boy.

The Raphael that is famous today and was idolized in the nineteenth century is a much simpler and more anodyne painter than the one that was divinized in 1520. All of those small “dear Madonnas” so celebrated for their sweetness were early modest works, probably made on spec, before he had received any of his grand commissions, and so were not much reproduced or widely praised in his day. The School of Athens, now famous for its seemingly perfect evocation of a harmonious classicism, was also little known, as it was painted in one of the pope’s private apartments and so, unlike the Transfiguration, could be seen only by a select few.

It is precisely because Raphael was apotheosized after his demise as no artist had been before him and became the chief god in the artistic Pantheon that we have inherited such a distorted vision of his art. The mythmaking, begun during his life and dramatically amplified by his death, has narrowed our view of Raphael, who was celebrated in the sixteenth century for his broad range of abilities. Vasari and others hailed Michelangelo as a master painter of one supreme subject—the heroic male body, made in God’s image. Raphael was, in contrast, infinitely flexible, a painter of male and female, old and young, people, animals, and plants.

Many have discussed the range of Raphael’s art, and since the mid-twentieth century the Transfiguration has been recognized to be his creation and a key to understanding sixteenth-century Italian painting. This book takes as its starting point a much less well-known aspect of his broad legacy, a strange, exotic, rather ugly invention—Raphael’s ostrich (fig. 3). The bird is an attribute of Justice, painted in shadowy oils on the wall of the Sala di Costantino in the Vatican Palace. Justice is usually shown upright and forward facing, as the embodiment of rectitude, not as such a sensual creature with a sidelong glance. Her left hand holds the scales, a standard attribute. Her right hand curves gently, almost tenderly, around the neck of a large, about half-life-size ostrich. The ostrich, emerging from the shadows, is easily identifiable by its size, its almost grotesque proportions—skinny legs, bulbous body, long sinuous neck—and its ugly, short-beaked, beady-eyed head.

<insert fig. 3 about here>

<1> The Sala di Costantino and Raphael’s Ostrich

Vasari tells us that the dead Raphael was laid out, with the Transfiguration above his head, in “the room in which he was working.” This could be a studio in his house or the Sala di Costantino, a reception room in the Vatican palace that he had begun painting for Pope Leo X. In October 1519 scaffolding was erected for Raphael to paint in the room. Less than a week after Raphael’s death the following April, Sebastiano del Piombo began to petition for the right to finish the room, surely not only because it was a prestigious papal commission but also because whoever gained this boon would assume the mantle of the master, becoming Raphael reborn. The room was a semipublic reception room and banquet hall, much more accessible to artists and patrons than the pope’s private apartments around the corner, and therefore a high-profile commission.

After some squabbling (recorded in a series of sometimes nasty letters) between Sebastiano del Piombo, backed by Michelangelo, and the members of Raphael’s shop, the honor of finishing Raphael’s final work was given to Raphael’s chief pupils, Giulio Romano and Gianfrancesco Penni. The painting of the room was completed a little more than four years later, under Pope Clement VII. The room is full of complex illusions—the scenes of the life of Constantine are painted as if they were tapestries, pulling at the nails from which they hang and curling slightly at the corners (fig. 4). Between these narratives are portraits of the popes, in niches as if they were statues, but flesh colored. The portraits are flanked by allegorical personifications of virtues. The allegories are not the standard types but inventive figures with strange clothing and attributes, including Justice with her ostrich.

<insert fig. 4 about here>

Two figures are painted in oil, Justice and the classical virtue of Comitas, a pleasant mildness (figs. 3, 5), setting them apart from the rest of the decoration of the room, which is done in fresco, the more traditional and less technically demanding technique for wall painting. These two figures were likely painted during Raphael’s life, whereas the rest of the room was finished after his death. When Raphael’s followers were given the commission to finish the room, they were unable to master the demanding oil mural technique and so had the walls stripped and reprepared for fresco. They seem to have left their dead master’s two figures painted in oil out of reverence for him, despite the risk that these would look incongruous next to the lighter colors of fresco. Scholars who mention this work focus on the attribution of the Justice, whether it was painted by the master himself before he died or by his pupils after his death. The obsession with whether it was Raphael’s hand that physically painted these figures is partially a product of the divinization of the artist. One of Raphael’s great innovations was his ability to run a large workshop and to give the artists in it an unusual degree of autonomy. Vasari mentions the members of this shop, criticizing paintings that he deems not sufficiently by Raphael. He crystallizes the myth of the purity of a painting made by the divine hand of the artist in his account of Raphael alone painting the Transfiguration, the face of Jesus being the last thing he touched. Vasari, who himself was the impresario of a large and efficient shop, had to know that this was false. In the Renaissance, a famous artist’s hand was prized, and so contracts would stipulate how much of the painting the master was to execute and how much would be left to assistants. With the burgeoning workshops of Raphael and Vasari, in which the master was sometimes purely the inventor of imagery, leaving the execution to his assistants, the insistence on the mythical status of the artist’s hand is almost nostalgic. Justice is, regardless of how much his hand held the brushes that painted it, Raphael’s invention, based closely on his drawings. Giovanni da Udine, Raphael’s assistant who was an expert in animal painting, surely painted the ostrich on the wall. The ostrich is nevertheless Raphael’s, as much a part of his endlessly inventive art as the many other sections of his paintings executed by others.

<insert fig. 5 about here>

Comitas has one bare breast, an armband like that on a classical statue of Venus, and has her foot on a lamb. These are not standard symbols for any virtue, and if the figure were not labeled, she would be unidentifiable. Comitas, pleasant softness or mildness, is also hardly a traditional Christian virtue. The other figure painted in oil, Justice, is easily identifiable not only from the written label but also from the scales she holds. She, like Comitas, has one bare breast. This is appropriate for an allegory—it shows that she is not a real person but a classically inspired personification of an idea. Later it would become standard to show personifications in this way, but this kind of revealing asymmetrical dress was not a convention until Raphael made it so in the Sala di Costantino. In the fifteenth century, allegorical personifications, which are almost always female, are shown decorously clothed, with the exception of Truth, who is naked because she is completely exposed. In antiquity, Amazons are shown with one bare breast, but personifications of ideas are not. Raphael is being rather daring in exposing the breast and giving this figure a relaxed, open-legged pose and almost lazy sensuality. The lack of any tailoring of the garment—it is more of a sheet tucked around her than an Amazon’s tunic—only adds to the sensuousness of the figure, making it seem as if we could almost touch this abstract idea.

Justice’s profile, classicized head, and odd, distinctive headdress—a kind of visor with two braids wound around it—are in direct imitation of Michelangelo’s Erithrean Sibyl on the Sistine ceiling (see fig. 67). This is more criticism than flattery, as Raphael softens and feminizes Michelangelo’s Herculean figure, gives the body an easy, graceful twist, and obscures the edges of the forms in atmospheric shadows. Perhaps in order to create this dark, smoky effect, so different from Michelangelo’s stony crispness, Raphael painted this figure in oil. Raphael was a renowned fresco painter, but despite his expertise and the well-known technical problems with oil murals, he chose to paint in oil, to create a sfumato reminiscent of Leonardo’s works. When painting the soft twisting form of a woman and a large bird, Raphael must have been thinking of Leonardo’s famous depiction of Leda and the Swan (now known to us only through copies and preparatory drawings).

The association between the ostrich and justice comes from ancient Egypt, where the ostrich feather was the hieroglyph for justice, as was known in Pope Leo X’s Rome. Even though the hieroglyphic code would not be broken for centuries, the hieroglyph for justice is described in a late Alexandrian text that humanists plumbed. Raphael’s mysteriously dark ostrich evokes these arcane meanings but does so in a modern way, as the bird is no flat symbol or fanciful monster but a meticulously observed creature, probably drawn from life using a bird in the pope’s menagerie. Raphael, by facing the bird forward, hides the tail feathers that denote justice and so refuses to make the creature a straightforward symbol. The overall meaning of the allegory is clear, but the ostrich demands an explanation. By creating a large naturalistic animal that evoked many disparate associations, a modern hieroglyph, Raphael forced the viewer to consider how the natural world is imbued with meaning. This issue came to a crisis by the end of the sixteenth century, with the rise of the foundations of both modern art history and natural history. Raphael’s invention was certainly not the only way to endow images with meaning, but it raises the question that became central to ongoing debate about art in the cinquecento, namely, how physical form contains and communicates inner truths. In this sense Raphael started the culture wars over the nature of images, which raged in the sixteenth century and were foundational for later Western art. Therefore, even if the late sixteenth-century scientist Ulisse Aldrovandi, for example, was not consciously reacting to Raphael’s ostrich, Aldrovandi’s idea of art, its possibilities, and its limitations would not have been possible without Raphael.

A humanist at Pope Leo X’s court, probably Pierio Valeriano, the great scholar of all things Egyptian, must have informed Raphael that the ostrich feather was the hieroglyph for justice. Raphael did not simply illustrate this idea but created an enigma, rich with possible associations, a poetic juxtaposition of beautiful woman and ugly bird, abstract ideas that take on unexpected flesh, sinew, and feathers. In doing so, Raphael claimed a new power for art, as something in between the representation of nature and allegory, neither breathtakingly real nor abstractly symbolic. The ostrich seems present but cannot merely be an ostrich, far removed as it is from any natural habitat. Likewise, the scantily clad woman cannot actually flank the pope without scandal, and the heroic narrative is depicted as a tapestry that curls at the edge. Art here does not create a plausible illusion and thus illustrate or compete with textual narratives—the painting is not a window onto the world. Art offers playful and impossible juxtapositions, levels of reality and illusion, and a slippery slope between historical truth and fantasy. Allegories would seem to be the images that are most at the service of texts in that they are literal visualizations of written attributes, offering little scope for fantasy, play, or the sort of divine ability to make living creatures for which Raphael was famed. Raphael, however, used allegory to claim a new status for art as a poetic language in its own right. Allegory, which means “other speaking” in Greek, is the embodiment of an idea in a completely different form. Languorous Justice and her fierce ostrich dramatize the dissonance of allegory, making the gap between the idea and its embodiment teasingly evident and thus liberating the image from a slavish dependence upon the word. God’s fantasy in creating weird hybrid monsters, such as the ostrich, inspires a like fantasy in the artist, also a maker of grotesques, in that he couples unlike creatures for impenetrable reasons in order to make monstrous art. Raphael’s art is neither a mirror of nature nor an illustration of a text; it is a series of juxtapositions that call attention to his artistry and cause the viewer to question the very nature of the image and how to read it.

<1> The Ostrich in the Renaissance

The ostrich is an African bird, an exotic curiosity that was painted on European maps of Africa, alongside elephants, hippos, and the monstrous peoples who were thought to inhabit the continent. Ostriches were kept in courtly zoos in Europe along with other exotic creatures, and ostrich eggs and plumes were treasured imported commodities. Sixteenth-century travelers who published popular accounts of foreign lands described ostriches running wild in Africa, being hunted and even cooked and eaten.

The ostrich was thought to be a curiosity—a marvel, a monster—because of its enormous size and inability to fly. It is the largest of birds, has the largest eyes of any land animal, with long eyelashes, and is the only bird with two toes on each foot. These and other peculiarities made it, according to ancient, medieval, and Renaissance scientists, a liminal creature, part bird, part beast. In fact, the Latin term for ostrich is struthiocamelus, or “sparrow-camel.” Many medieval and Renaissance images of the ostrich show it as a bird with camel’s feet. As a hybrid monster, it is like the mythical griffin and sphinx. There are, however, no classical myths about ostriches. Ovid does not describe anyone changing into an ostrich, and no ostriches run through the Odyssey or the Aeneid. During the Renaissance, therefore, ostriches were not associated with any one idea or narrative. Instead, they evoked a host of different, often contradictory ideas.

Raphael’s is by no means the first ostrich in Western culture. Ostriches had already reared their strange heads in the Hebrew Bible, ancient Egyptian rites, classical Rome, medieval manuscripts and cathedrals, and early Renaissance palaces. Through the centuries the bird carried a host of meanings—some positive, some negative—signifying by turns heresy, stupidity, perseverance, heat, and the miraculous conception of Jesus, to name a few. This is also true of other animal imagery in the Renaissance: peacocks, for example, can signify both virtue and vice. Renaissance art is a complex and evocative language, for which no meaningful dictionary can be written. The ostrich, though, is peculiarly ambiguous, partially because its image was always uncommon and so, like a rare word, not easily interpreted. Though the ostrich could mean many things throughout the Middle Ages, it was not an attribute of Justice. You have to return to ancient Egypt to find any precedent for Raphael’s invention.

Tracing the complex history of shifting interpretations given to the ostrich in scientific texts, literature, and religious writings and images of antiquity and the Middle Ages demonstrates the variety of ways people made sense of this living monster, with its strange habits. Since ostriches were kept in zoos and hunted as a part of courtly pageantry, writers and artists attempted to describe and explain the aberrant features of the actual bird—its size, its apparently useless wings, and its potentially deadly two-toed feet. The ostrich, however, in a parallel tradition, also acted through the centuries as an abstracted symbol, its weird physiology and habits crystallized into a simple memorable image that could deliver a moral message. As a symbol it took on a classical Renaissance form in dozens of images in fifteenth-century Urbino, the sophisticated court where Raphael was born and raised. He drew upon many strands of this rich tradition and, in a move both traditional and radical, created a modern hieroglyph that embodies arcane ancient meanings in an unprecedentedly naturalistic form.

Raphael’s ambiguous exotic image was not made for the private pleasure of the pope, who was known for his love of exotic animals, but instead for the Sala di Costantino, a semipublic reception room visited daily by ambassadors and other dignitaries. It is hard to imagine what they made of Raphael’s ostrich as a personification of papal virtue. The incongruous nature of this image, in a space that would seem to demand more forthright rhetoric, is particularly pointed given that the room contains otherwise explicitly pro-papal propagandistic imagery—scenes of the life of Constantine—particularly after Clement VII changed the program to include the Donation of Constantine, the much-contested moment when, according to the popes, the Roman emperor gave the papacy control not only over religious matters but also over the earthly government of the western empire. Ambassadors would have been struck by the blunt message of the Constantinian scenes and the laudatory portraits of the popes but might have been tempted to misinterpret the scantily clad women who flank them, especially the one fondling an ostrich, as figures of the corrupt decadence of the papacy.

Martin Luther and his followers seemed to pose little threat when Raphael was first asked to paint the Sala di Costantino, but over the course of the century, as the Reformation gained in strength, the popes responded by seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within, to make it less easily assailable. By the 1560s, the Council of Trent had decreed that art should be decorous and comprehensible and should not contain anything shockingly new, and thereafter works of art were censored, most famously Michelangelo’s Last Judgment. Theologians decried elitist, unclear art. Raphael’s ostrich, despite its oddity and ambiguity, was, however, never criticized or censored. Instead, artists imitated this image throughout the sixteenth century and the centuries that followed. Because Raphael was enshrined as a god of art on his death, his ostrich, a new and strange invention in 1520, almost immediately became, in and of itself, a kind of a classic, which could be imitated, emulated, and satirized. Among those who saw the ostrich as a vital part of Raphael’s legacy was Giorgio Vasari, who, even as he was constructing the enduring literary image of Raphael in his famous biographies of the artists, made images with ostriches in tribute to and competition with Raphael.

Sixteenth-century artists depicted ostriches as images of justice but also gave the ostrich new meanings. Men and women played memory games that involved ostriches, included ostriches in antique-inspired grotesque decorations, collected prints of ostriches, made scientific studies of ostriches, wrote poems about ostriches, invented fantastic ostrich tableware, and painted and sculpted the flightless bird in churches, palaces, and villas. Many of these ostriches, are, like Raphael’s painting, naturalistic, and so the ostrich becomes vividly present in the most unlikely of places, a celebration of illusionism and at the same time obviously a fiction. Some of these ostriches are not freighted with any moral or allegorical import—they are exotic beasts, to be admired as marvels in their own right, a new kind of art without a message. Other artists and writers in this self-conscious age adopted and transformed Raphael’s invention in order to outdo or subvert it. Raphael’s evocative and ambiguous painting inspired not only these elite intellectual games but also terribly personal imagery. The alien ostrich, with its arcane meanings, came to connote men’s and women’s characters and the violent events of their lives. Ostriches expressed the toughness of warriors, the plight but also the strength of a woman who was a political pawn, the nobility of a ruler, the tyranny of another, and the bitterly frustrated political aspirations of those who could not change with the times. The story of Raphael’s ostrich, therefore, became intertwined both with larger histories—of the idea of art, the development of science, and the Counter-Reformation—and with the personal lives of the people who struggled and triumphed in these turbulent times.

In light of those images that came before and those that followed after, Raphael’s ostrich illuminates a weird, lesser-known side of Raphael and therefore of the Renaissance. The strangeness of Raphael’s ostrich bears ancient arcane meanings but is not a fabulous fantasy. Raphael’s painting and the many ostriches that followed are founded upon an acute observation of the real oddity of living beasts, and so these images of hybrid creatures are both marginal and central to major cultural shifts in attitudes toward nature—at the crossroads of art, religion, myth, and natural history.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.