The Salem Belle

A Tale of 1692

Ebenezer Wheelwright, Edited, with an introduction and notes by Richard Kopley

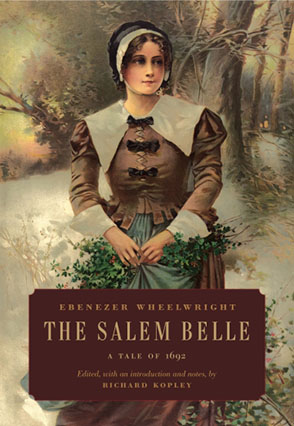

The Salem Belle

A Tale of 1692

Ebenezer Wheelwright, Edited, with an introduction and notes by Richard Kopley

“It is wonderful to have The Salem Belle back in print, edited expertly by Richard Kopley. Published eight years before The Scarlet Letter, Ebenezer Wheelwright’s novel was an important part of the cultural mix behind Hawthorne's masterpiece, as Kopley demonstrates in his perceptive introduction. The Salem Belle also stands on its own as a thought-provoking novel about Puritan times written from the perspective of nineteenth-century America.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Hawthorne scholar Richard Kopley, who has recovered The Salem Belle for twenty-first-century literary study, introduces and annotates Wheelwright’s novel, providing relevant historical details as well as pertinent details about Wheelwright’s life and reading. Kopley also furnishes three appendixes that will facilitate understanding of The Salem Belle and further analysis of its place in American literary history.

“It is wonderful to have The Salem Belle back in print, edited expertly by Richard Kopley. Published eight years before The Scarlet Letter, Ebenezer Wheelwright’s novel was an important part of the cultural mix behind Hawthorne's masterpiece, as Kopley demonstrates in his perceptive introduction. The Salem Belle also stands on its own as a thought-provoking novel about Puritan times written from the perspective of nineteenth-century America.”

“Richard Kopley’s discovery that Ebenezer Wheelwright’s The Salem Belle (1842) was a precursor to Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850) is substantiated by his careful and perceptive attention to detail. The novel itself is fun and quirky and explores the kinds of historical and cultural issues that also motivated Hawthorne. Kopley’s argument is sound, clear, and persuasive, and the connections he makes are right on target.”

“Richard Kopley has provided a valuable service by making available this historical work about Salem, which served as one of the sources for The Scarlet Letter. Not only is it interesting to look for intertextualities between the two books, but this work stands on its own as a fascinating portrait of the turbulent times it describes.”

“Hawthorne scholars will be intrigued by Richard Kopley’s claim that several passages toward the end of The Salem Belle inspired passages in the forest and New England holiday sections of Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Reprinting The Salem Belle also contributes an additional text to conversations about the witchcraft hysteria that many people, especially students, probably know from Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. The novel provides another fictional window onto seventeenth-century Boston and Salem society—especially the social and religious scenes. It is an easy read, and when the plot thickens with the vengeance-inspired accusations that Mary Lyford is a witch, it is compelling.”

Ebenezer Wheelwright was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1800. He spent most of his professional life as a West Indies merchant in Boston.

Richard Kopley is Distinguished Professor of English Emeritus at Penn State DuBois.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Note on the Text

Introduction by Richard Kopley

The Salem Belle: A Tale of 1692

Appendix A: Publication History of The Salem Belle

Appendix B: Reviews of The Salem Belle

Appendix C: Scholarship on, and Scholarly Mention of, The Salem Belle

Notes

Introduction

Richard Kopley

Commenting on what the family had had for dinner—“a piece of beef ‘with a streak of fat & a streak of lean’”—Isaac G. Reed, of Waldoboro, Maine, wrote on January 26, 1843, to his daughter Mary, then in Boston, “It might well have pleased Jack Spratt & his wife, tho I think they could not have ‘licked the platter clean,’ unless they were of the dimensions of the sons of Anak, or had the voracity, which Lyford & Henry must have had when they arrived at Worcester after having ‘put up’ eight days in ‘the shed,’ with blankets enough for themselves & horse & to make a curtain besides.” Reed easily relied here on a nursery rhyme, still familiar today, “Jack Sprat,” and on a biblical phrase perhaps less familiar today, but accessible, “the sons of Anak,” the giants who were found by Moses’s spies in the land of Canaan. But utterly unfamiliar today is Reed’s reference to “Lyford & Henry” in Worcester, Massachusetts, after eight days in the shed. Who were Lyford and Henry? What shed? Reed’s source, as he soon acknowledged, was the 1842 novel The Salem Belle, a tale of love, vengeance, and guilt, set against the Salem witchcraft delusion of 1692. It is an engaging work whose recovery today is warranted on its own merits—and then additionally for its critical importance in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter.

Reed continued, “So far & a little farther, I have read in ‘The Salem Belle.’ I have gotten to the time when Trellison procures the name of the belle to be added to the list of the proscribed, & I think [the] book, so far, well written—especially the sermons of Willard & of Mather. I have read without an effort to discover ‘inconsistencies,’ and therefore have found but few. And I am too little versed in the niceties of history to detect anachronisms or other errors.” Mary’s father had read more than half of the book. He had encountered, among other incidents, James Lyford and young Henry taking refuge during a snowstorm in a shed outside of Worcester as they journeyed by sleigh from Hadley, Massachusetts, to Boston, and he had come upon the two dramatic sermons at the center of the novel (Salem Belle, –, –) and the subsequent accusation of witchcraft by Trellison, the rejected suitor, against the beautiful young woman who had turned him down, Mary Graham—James Lyford’s sister—“the Salem belle” ().

Perhaps Reed had his daughter Jane Ann’s copy of the novel, in which she had written “By Mr. Wheelwright.” An earlier letter to Jane Ann’s sister Mary from a friend, Sarah R. Derby, asked, “Have you seen Mr. and Mrs. Wheelwright lately? Have they moved from Dover Street? Please give my love to them.” A quick check of Boston directories reveals that the “Mr. Wheelwright” who had moved from Dover Street was Ebenezer Wheelwright. And he had moved to 3 Temple Place, the address of Charles Tappan, of the firm Tappan and Dennet, the publishers of The Salem Belle. Indeed, the author had inscribed a copy of the book, in October 1842, to poet Hannah F. Gould, “with the kind regards of E. Wheelwright.” And his later book, Traditions of Palestine, resonates with the plot and language of this earlier one. Ebenezer Wheelwright was the anonymous author of The Salem Belle.

Born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1800, Ebenezer Wheelwright early on became a bookseller in Newburyport and a flour merchant in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but he spent most of his professional life, forty years, as a West Indies merchant in Boston, with particular attention to Santo Domingo. He was not successful—he acknowledged in his petition for bankruptcy in 1842 an astounding indebtedness of $33,479.31. (Perhaps his bankruptcy explains his then publishing anonymously.) Credit ratings made between 1856 and 1874 culminate with the comment “He is honest enough, but has been poor for years & hardly makes a living. Has no real basis for cr[edit].” Wheelwright was married and had three children who lived to adulthood; he died in Newburyport in 1877.

One obituary writer excused his financial failure thus: “Himself of sterling integrity, he placed too much trust in the good intentions of others. This ill-timed credulity neutralized his considerable business ability, and robbed him of the well-earned fruits of a life of toil.” But that life of toil also included the literary kind, which, though doubtless not particularly profitable, did yield interesting work, particularly the two novels The Salem Belle and Traditions of Palestine. Both offer a Christian piety—in fact, the latter, which includes as an alternate title Scenes in the Holy Land in the Days of Christ, concerns, in part, the life of Christ. Wheelwright was a religious man and a “pillar in the church.” Additionally, he edited a Congregationalist magazine, the Panoplist, in 1867 and 1868 and contributed to the Congregationalist, finally giving his name, “Eben Wheelwright.” Notably, one of his articles in the Congregationalist, about evangelical preaching, was reprinted posthumously, slightly trimmed, in the collection Worth Keeping. Wheelwright’s piety was certainly at odds with the bolder thought of the transcendentalists, but that piety is nonetheless worthy of study. And its presence in The Salem Belle confirms that there was a counterpart to the vital tradition that lay beneath the American Renaissance.

The Salem Belle is a short historical novel set primarily in Boston and Salem during 1691 and 1692. It is a work in which a young man, Trellison, who has been disappointed in love, mistakes his wish for vengeance for religious zeal. The basic plot may be set forth briefly. According to an introductory letter, it was based on a story remembered and written down by one “J. N. L.” of Cumberland County, Virginia. In Wheelwright’s reworking, a Harvard student and a recent Harvard graduate, the upright Walter Strale and the devious Trellison, seek the same young woman, the lovely and devout Mary Graham. Understandably, she accepts Strale and rebuffs Trellison. Hurt and bitter, Trellison seeks revenge. The intensifying witchcraft frenzy in Salem presents him with an opportunity: he can accuse Mary of being a witch.

The Salem witchcraft frenzy was precipitated by young girls’ accusations of others, strengthened by supposed confessions, and given credence by ministers, judges, and government leaders. A critical aspect of the event was the belief in “spectral evidence”—that is, that accused people appeared as apparitions and afflicted the accusers. Various explanations of this painful episode in Salem have been offered, including social and political conflict in Salem Village and fear in Essex County owing to the ravages of King William’s War (the Second Indian War) in Maine. As a result of the growing persecutions, fourteen women and five men were hanged on Gallows Hill, and one man was pressed to death. This dark event has endured in our literature, most famously in Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible, which employs the Salem persecutions to critique the persecutions in the early 1950s of those who may have once had a connection to the Communist Party or who knew people who may have once had a connection. The Salem Belle represents an earlier use of the Salem witchcraft debacle, a work that also targets persecution.

The story in The Salem Belle is told with a blend of narration, description, and dialogue—this last diminishing as the action increases. Wheelwright presents the conflicting views—the view of reason, articulated by Samuel Willard of the South Church, and that of superstition, argued by Cotton Mather of the North Church—in the novel’s central sermons. But Trellison’s schemes inevitably proceed. And so, too, do the efforts of Strale and Mary’s brother, James Lyford, to rescue Trellison’s victim. Strale and Lyford are assisted by William Somers, a devotee of the revered William Goffe, who had passed judgment against King Charles I of England in 1649, had fled England under King Charles II in 1660, and had then lived in Hadley, Massachusetts, where he had been—in this novel, at least—the grandfather of Mary and James. The climax of the novel, set on Gallows Hill, is memorable and compelling.

The tone of the novel is earnest and cautionary—clearly Wheelwright had his “young readers” (Salem Belle, ) in mind, along with his older ones. There are attempts at comic relief—interludes with Strale’s slave, Pompey—but they are neither comic nor a relief. And as we may be concerned about the depiction of Pompey, we should remember that he is one of many flawed characters in the novel, that he does succeed in delivering Strale’s letter to James Lyford in the snowstorm, and that Wheelwright himself was antislavery. The burden of the novel thematically is a serious one: the virtue of piety, the danger of superstition. It is an explicitly Christian theme, perhaps closer to the thought of Mary Moody Emerson than to that of her nephew Waldo. Wheelwright speaks for purity and simplicity, Providence and the Last Judgment and the hereafter. He is a Congregationalist, distinct from more liberal Christians, Unitarians. And Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and other transcendentalists represent a radical rethinking religiously, even more liberal than Unitarianism. Indeed, Emerson wrote in 1841 in “Spiritual Laws” that “the theological problems of original sin, origin of evil, predestination, and the like” are just “the soul’s mumps and measles, and whooping-coughs.” But Wheelwright’s traditional religious thought is just as sincere and authentic as Emerson’s dismissal of such thought—and it conveys a vital feature of mid-nineteenth-century American culture, the context against which transcendentalism emerged. And the value of traditional religion remains an important issue for twenty-first-century readers.

With well-chosen details and a mix of affection and outrage concerning early New England, Wheelwright simply and effectively presents a dark time. He deftly blends the historical and the imagined, at an increasing pace. And he aptly refers to other texts throughout. Not surprisingly, most of Wheelwright’s references are biblical. The thoughtful and deliberate Willard, in his sermon, fittingly elaborates 1 John 4:1 (King James Version), “Beloved, believe not every spirit” (Salem Belle, ), while the incendiary Mather chooses Isaiah 28:15, “your agreement with hell shall not stand” (). Earlier, after the earthquake, Mather advises, “The voice we have just heard is the voice of a father telling us to hide in these chambers of his grace, ‘until the indignation be overpast’” (Isaiah 26:20; Salem Belle, ). The fanatical Trellison ranges from presumptuously advising Mary about the power of the “Sun of righteousness” (Malachi 4:2; Salem Belle, ) to later plaintively crying, “Accursed be the hour that gave me birth” (Jeremiah 20:14; Salem Belle, ). Walter Strale notes appropriately, “The wicked flee when no man pursueth” (Proverbs 28:1; Salem Belle, ). And the narrator himself relies on biblical allusion, as when he refers to “hope deferred” (Proverbs 13:12; Salem Belle, ) and to “that inestimable pearl” (“the kingdom of heaven,” “one pearl of great price,” Matthew 13:45–46; Salem Belle, ). The notes reveal additional biblical references. But the author refers to literary and historical works, as well.

Wheelwright contrasts early Boston to the Boston of his time, the latter with “streets of palaces and walks of state,” thus comparing the nineteenth-century city with the elegant Troy of book 6 of Homer’s Iliad (Salem Belle, ). He considers “worldly happiness” to be for Mary as alluring as the “song of the sirens,” thereby alluding to the enchanting but dangerous voices of the harpies in book 12 of Homer’s Odyssey (). He characterizes the tranquil townspeople of Hadley by quoting a quatrain from Thomas Gray’s 1751 “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” a work that honors those who lived and died in obscurity (). And he characterizes Mary in her forest retreat in Salem by quoting lines from William Cowper’s 1782 “Retirement,” a work that celebrates devout meditation in nature (). Wheelwright also has occasion to quote from then-recent historical books—with regard to the tree on Gallows Hill, from Abel Cushing’s 1839 Historical Letters on the First Charter in Massachusetts Government (); and with regard to the guilt of Chief Justice William Stoughton, from Harvard president Josiah Quincy III’s 1840 two-volume The History of Harvard University (). And he cites admiringly the writings of Robert Calef (), whose 1700 More Wonders of the Invisible World was a powerful response to Cotton Mather’s 1693 Wonders of the Invisible World. For a businessman who had never gone to college, Wheelwright seems to have been pretty well read. And his reading gracefully informs his novel.

Some of Wheelwright’s literary techniques are immediately evident. For example, the ominous foreshadowing—the wolf and the wildcat (), the hurricane (–), and the earthquake (), anticipating the tragedy to come—is readily apparent. Less apparent, however, is the formal balance. We may note that the introductory letter speaks of “bold and startling theories, which can only waste the mental energies, and make shipwreck of the mind itself on some fatal rock of superstition or infidelity” and refers to the “Temple,” the Bible, as possessing “perfect symmetry” (). Wheelwright later writes of Judge Samuel Sewall confessing in church, “presenting his own example as a warning to future magistrates to avoid that fatal rock, on which justice and mercy had alike suffered shipwreck” and also of the “perfect symmetry” of the spars of the schooner, the Water Witch (). The phrase “perfect symmetry” calls attention to the verbal symmetry of which it is a part. We may also observe, a bit further in from the beginning of the novel, the appearance of the Sea Gull, with Captain Wing, then a foolish escapade involving Pompey (, ), and later, a bit further in from the end, another foolish escapade involving Pompey, then the coming of the Water Witch, with Captain Ringbolt (, ). Somewhat closer to the center, Trellison reveals the identity of the woman with whom he had been walking—“The name of the lady . . . is Miss Graham”—and “Walter started at this annunciation” (); not long after the center, Trellison accuses the same woman of witchcraft—“I pronounce the name of Mary Graham”—and “Mr. Parris started from his seat” (). And more symmetrical framing is provided. Finally, at the well-framed center—in the ninth and tenth chapters of an eighteen-chapter novel (– and –, respectively)—are the balancing sermons, Willard’s and Mather’s. These constitute the central fulcrum on which the novel rests. Wheelwright’s pride in his rendering of these sermons is suggested by his reprinting that rendering, a set piece, as “A Sabbath in Boston in 1692” in the November 1868 issue of the Panoplist.

Wheelwright’s first novel received mixed reviews. (For a reprinting of twenty-five recovered reviews of The Salem Belle, see appendix B. The page number in the present volume for each quoted passage from a review in this appendix is given here parenthetically.) The one review that seems to reflect a knowledge of the anonymous author is that from the January 1843 issue of the Pioneer (a review probably written by editor James Russell Lowell), which begins, “This little novel is, we are informed, the production of a young merchant of this city, whose first attempt in the art of book-making it appears to be” (). Stating that “the story is one of love, and is pleasingly told,” this reviewer was agreeing with some earlier reviewers, who had also praised the work: “The Salem Belle is a simple and beautiful tale, and is beautifully written” (Boston Evening Bulletin, qtd. in the Salem Register, December 5, 1842, ), “The style of this little book is easy and graceful” (New York Daily Tribune, December 6, 1842, ), “This story is well and movingly told” (American Traveller, December 9, 1842, ). Yet others disagreed: “We have perused this book as closely as its inordinate dullness would allow” (Boston Post, December 5, 1842, ), “It is an agreeable and entertaining, but not particularly powerful story” (Knickerbocker, January 1843, ), “The present attempt is of a more humble order, and contains some evidences of want of practice or ability in the author” (Boston Miscellany, February 1843, ).

A specific concern was one that Isaac G. Reed had mentioned, anachronisms. Although Reed couldn’t find any, the Boston Post reviewer complained, “The characters talk just as they do now-a-days” (), and the Pioneer reviewer objected to the mention of “lightning conductors” and sentiments suggestive of the “Declaration of American Independence.” But this latter reviewer adds, “These, however, do not probably mar the interest of the book to the general reader” ().

Wheelwright wrote that “true religion” is “the best antidote against superstition” (Salem Belle, ), and one reviewer observed of The Salem Belle, “A highly religious feeling pervades the whole volume” (Artist, January 1843, ). Another reviewer saw the book itself as the antidote: “There are delusions almost as lamentable as that of the Salem Witchcraft which still linger in the land, and it is by way of antidote to such poison that the volume in question is offered to the public” (Albany Evening Journal, December 16, 1842, ). Yet another reviewer saw the book itself as the poison: “If parents wish their children to acquire a taste for novel reading, so that they may be ready to devour every fictitious work that comes in their way, with all the poison it may contain, this is a good work for them to commence with” (New England Puritan, December 9, 1842, ). And some reviewers specifically faulted The Salem Belle for presenting the Puritans too harshly: “Those writers who directly or indirectly would stigmatize the faith of the Puritans, never tell us that other men believed and acted in like manner” (New-York Evangelist, December 8, 1842, ); “We cannot help thinking that [The Salem Belle] bears too severely upon the motives of some of the eminent divines—Cotton Mather in particular” (Boston Recorder, December 30, 1842, ).

The book enjoyed popularity in its time—it went into a second edition in 1847. And inscriptions in copies of The Salem Belle reveal that it was given as a gift from mother to daughter and from friend to friend. Most interesting of all, it was used as a crucial source-text by Nathaniel Hawthorne in The Scarlet Letter.

Hawthorne would have known of the book from the reviews—especially the review in the January 1843 issue of the Pioneer (one preceded by a positive review of his own Historical Tales for Youth). Hawthorne would soon have two of his short stories, “The Hall of Fantasy” and “The Birth-Mark,” featured in his friend Lowell’s magazine. He might also have learned of the book from Lowell himself and from sister-in-law, bookseller, and book publisher, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody. Most suggestively, the publisher of Hawthorne’s Historical Tales for Youth was also the publisher of The Salem Belle: Tappan and Dennet. Perhaps, when Hawthorne visited Boston from Concord in late October 1842, he visited his publisher on 114 Washington Street and was told of The Salem Belle—and even given a copy. After all, his son, Julian, wrote, “Some volumes [Hawthorne] bought; but most of them came either as gift copies from their authors, or from Ticknor and Fields, and other publishers.” And it is clear that Hawthorne read novels broadly—as his sister Elizabeth stated, “He read a great many novels; he made an artistic study of them. There were many very good books of that kind that seem to be forgotten now.”

We do not know what Isaac G. Reed thought of the later chapters of The Salem Belle, but we can infer that Hawthorne was attracted to them, for he transformed three passages from these chapters for the later chapters of The Scarlet Letter. The first passage from The Salem Belle on which Hawthorne drew was that concerning Mary and her brother, James, in her sanctuary in the Salem woods. Sensing Trellison’s persecution of her and others’ suspicion of her, Mary confides all, and James responds, “Do not sink under this load of sorrow. . . . Deliverance will in some way be effected.” Dubious, Mary says, “I would that such a hope could send its reviving influence to my heart” and admits her longing for death. “Why speak so mournfully, dear Mary,” answers James; “This world is not yet a desert, which no flower of hope nor green beauty of summer can adorn.” But Mary is disturbed by ominous voices, and “the wind sighed mournfully along, as if in sympathy with the sadness which had fastened deeply on the minds of brother and sister.” James tries to reassure her, saying, “Time will soon disclose all; meanwhile, have courage, my dear sister.” Still, he warns, “Immediate flight is necessary” (Salem Belle, –). We may see that Hawthorne adapted this passage for his purposes. Hester Prynne and the reverend Arthur Dimmesdale, former lovers, meet in the forest outside Boston. Arthur—who has not admitted his part in the affair, as Hester has admitted her own—confesses to her his sense of guilt for his action and for his seemingly false achievement as minister, as well as his hopelessness. Hester reveals what she has not for seven years: that his physician was her husband. Hawthorne writes, “The boughs were tossing heavily above their heads; while one solemn old tree groaned dolefully to another, as if telling the sad story of the pair that sat beneath, or constrained to forebode evil to come.” The minister asks, “Must I sink down there, and die at once?” Hester, seeking to bolster Arthur, asks, “Is the world then so narrow? Doth the universe lie within the compass of yonder town, which only a little time ago was but a leaf-strewn desert?” She recommends that he escape to the west or back to Europe, and though he claims, “I am powerless to go,” she offers an impassioned encouragement, culminating in “Up, and away!” (Scarlet Letter, 189–98).

For this critical passage in The Scarlet Letter—the intense meeting of the two lovers—Hawthorne turned to a passage about the intense meeting of a brother and sister in Ebenezer Wheelwright’s novel. Supposed witchcraft becomes actual adultery, and the genders of supporter and supported are reversed, but the two passages feature evident parallels in description, in dialogue, and in emotional dynamic. And the resonance that we discern in these passages we may notice again in two additional pairs of passages.

It was the harbor passage in The Salem Belle that Hawthorne relied on next, with its focus on the “little schooner,” the Water Witch, and Captain Ringbolt. Particularly notable is that Ringbolt is viewed uncertainly in his business practices, yet is nonetheless accepted. Wheelwright writes, “How he obtained his merchandise was sometimes a mystery; but the Salem ladies were careful not to inquire too curiously into the matter; they were quite willing Captain Ringbolt should have his own way; and, as he was uniformly courteous and obliging, any suspicions would certainly be inexpedient, and perhaps unjust. It was rather wonderful, however, that so much charity was extended towards this gentleman, considering the very strict morals of the Puritans, and the rigid honesty with which they were accustomed to discharge their pecuniary obligations.” And Somers, who is helping Lyford and Strale in their rescue effort, boards the Water Witch to meet with the captain and secure passage for the three in his family (Salem Belle, , ). Hawthorne adapted this passage effectively. He refers in The Scarlet Letter to “a ship [that] lay in the harbour; one of those questionable cruisers, frequent at that day, which without being absolutely outlaws of the deep, yet roamed over its surface with a remarkable irresponsibility of character.” It is a “vessel . . . recently arrived from the Spanish main,” one that Hester boards to meet with the captain and obtain passage for the three in her family. Hawthorne writes later, “It remarkably characterized the incomplete morality of the age, rigid as we call it, that a license was allowed the seafaring class, not merely for their freaks on shore, but for far more desperate deeds on their proper element. The sailor of that day would go near to be arraigned as a pirate in our own.” Yet, he adds, “the Puritan elders, in their black cloaks, starched bands, and steeple-crowned hats, smiled not unbenignantly at the clamor and rude deportment of these jolly and seafaring men” (Scarlet Letter, 215, 233).

For his treatment of the anticipated escape ship and its men in The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne again turned to a passage in The Salem Belle. The correspondence in description, particularly as regards the surprisingly tolerated seamen, as well as a character’s seeking passage, confirms the pattern already noticed and invites an expectation of its continuing—an expectation that will be realized in the concluding scaffold passage in both works.

In The Salem Belle, when the sheriff tells the crowd gathered at Gallows Hill that the convicted Mary Lyford, “the criminal,” has escaped, “Trellison mounted the scaffold.” The guilt-ridden accuser, having realized that his seeming religious zeal had actually been personal vengeance, wishes to confess publicly. Wheelwright writes, “His face, which till now had worn the livid hue of death, was covered by the flush of emotion.” The crowd is rapt: “Every eye in that immense assemblage was fixed upon him.” And he speaks “the feelings which moved his inmost soul.” He says that because he had made a false accusation, God “didst turn back upon my soul a tide of guilt and horror” but has now “checked its rage” by permitting this act of atonement. “Hear me, magistrates and men, and ye ministers of an insulted God!” Trellison cries; “hear me, old age, middle life and youth!” And he makes his confession: “I proclaim in your ears that the maiden who has this day escaped death, was guiltless of the crime for which she was condemned to die! Deceived by my own heart, mistaking the bitter passion of revenge for zeal in the service of my Maker, it was this hand that brought down the threatened ruin upon that child of innocence and love.” Acknowledging the crimes that had been committed on this hill, he expresses gratitude to God that the planned additional execution did not occur. And after his confession, “the speaker descended from the scaffold” and “passed through the spell-bound and awe-struck multitude.” Once he vanishes into the forest, “an unbroken silence reigned for a few moments through all that vast assembly, and the first words that were spoken, were an expression of thankfulness that the innocent maiden had escaped.” Yet some people doubt the validity of the confession: “There were not wanting those who attributed this change in Trellison to the power of her magic arts” (–).

This, the climactic scene in The Salem Belle was transformed by Hawthorne for the climactic scene in The Scarlet Letter. Dimmesdale, having given his Election Sermon, now walks toward the scaffold; his face has a “deathlike hue,” but when he stops near the scaffold, his look is “tender and strangely triumphant.” He calls for Hester and Pearl, and with Hester’s support, he “approach[es] the scaffold, and ascend[s] its steps.” The people watch in amazement, “knowing that some deep life-matter—which, if full of sin, was full of anguish and repentance likewise—was now to be laid open to them.” “People of New England!” he proclaims; “ye, that have loved me!—ye that have deemed me holy!—behold me here, the one sinner of the world!” Finally, he says, he stands where he should have stood seven years ago. He states that Hester’s scarlet letter is only “the shadow of what he bears on his own breast.” And “with a convulsive motion he tore away the ministerial band from before his breast.” “For an instant,” Hawthorne writes, “the gaze of the horror-stricken multitude was concentrated on the ghastly miracle; while the minister stood with a flush of triumph in his face, as one who, in the crisis of acutest pain, had won a victory.” And speaking to Hester, Dimmesdale thanks God: “God knows; and He is merciful!” since he has allowed this atonement, “this death of triumphant ignominy before the people.” When the minister dies, “the multitude, silent till then, broke out in a strange, deep voice of awe and wonder.” Yet some deny the substance of the confession, saying that the godly minister had only been suggesting that all men are sinful (250–59).

Hawthorne honored the most extraordinary moment in The Salem Belle, making it, in The Scarlet Letter, even more extraordinary. There are differences, of course—the false accusation of witchcraft as opposed to adultery, life versus death—but the parallels are clear. In this, the third pair of corresponding passages, the description, speech, and, emotional dynamic are powerfully resonant. Given the correspondences in the two forest scenes, the two harbor scenes, and the two scaffold scenes, we may well wonder how Hawthorne might have written The Scarlet Letter differently had Wheelwright never written The Salem Belle.

Our recognizing the presence of The Salem Belle in The Scarlet Letter is not merely a matter of engaging in belles lettres—or perhaps Belle-Let—but rather a matter of facilitating interpretive insight. We may work toward this by wondering why Hawthorne relied on The Salem Belle in the first place.

Wheelwright’s authorship of the novel was not generally known since the work was published anonymously, perhaps because Wheelwright did not want his creditors to know that he’d been spending his time writing or to claim whatever modest income he earned from it. Yet the author of the review in the Pioneer, in all likelihood Lowell, seemed to know his identity. Probably Peabody knew his identity. Certainly Hawthorne’s publisher, and Wheelwright’s—Tappan and Dennet—knew his identity. It is fair to conclude, I think, that Hawthorne, well connected in literary Boston, would have known it as well. The Salem Belle is an engaging book for its theme, its setting, its characters, its language, and its form. Surely, Hawthorne, a student of Puritan history and a former citizen of Salem, would have responded to the work with interest—especially to its view of the inflexibility of the Puritans and the unreliability of spectral evidence. But, I would argue, it is the authorship of The Salem Belle that made it particularly important for The Scarlet Letter.

A critical clue, I believe, is Hawthorne’s twice mentioning Anne Hutchinson in The Scarlet Letter. He refers early on to the “sainted Ann Hutchinson” (48), and he later states that without her daughter, Pearl, Hester “might have come down to us in history, hand in hand with Ann Hutchinson, as the foundress of a religious sect” (165). Anne Hutchinson was the heroic woman who spoke for the internal evidence of divinity (“Covenant of Grace”) over the external evidence of divinity (“Covenant of Works”) in what has come to be called the “Antinomian Controversy,” lasting from 1636 through 1638. It was one’s private sense, Hutchinson argued, rather than public power and wealth that yielded true religious insight. She thereby challenged Gov. John Winthrop, Rev. John Cotton, and the other leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In a government founded on religious principles—a theocracy—any religious doctrine inconsistent with the approved doctrine threatened the authorities.

The odd thing is that although Hawthorne twice mentions Anne Hutchinson admiringly in The Scarlet Letter, he does not mention her partner in this important episode, a prominent minister and the husband of her sister-in-law, the reverend John Wheelwright. Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright are repeatedly linked elsewhere, as in the journals of John Winthrop. The two bravely defied the theocracy and were tried, convicted, and banished. In this context, the salient fact is that John Wheelwright was the great-great-great-great-grandfather of Ebenezer Wheelwright.

Hawthorne was ever attentive to ancestry—he asserted the sins of his great-great-grandfather William Hathorne and his great-grandfather John Hathorne in “The Custom-House” introduction (Scarlet Letter, 9–10). The former had been involved in persecuting Quakers, Hawthorne acknowledges, and the latter in persecuting those accused of witchcraft. Hawthorne might have added, too, that William Hathorne was a Salem deputy on the general court that ruled against Anne Hutchinson. This ancestor of Hawthorne and the most famous ancestor of Ebenezer Wheelwright had been on opposite sides of the Antinomian Controversy. Aware of Puritan history and genealogy, Hawthorne would not have missed the rich possibility of a novel about the Salem witchcraft mania by a writer whose name—never stated—directly linked that writer to Anne Hutchinson’s greatest ally. Persecution for supposed witchcraft in Salem was a type of the earlier persecution for supposed heresy in Boston. Never mentioning John Wheelwright in The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne could nonetheless subtly suggest him by repeatedly alluding to a work by his direct descendant. So, in this view, not only may Hester Prynne be associated with Anne Hutchinson, but also Arthur Dimmesdale may be associated with John Wheelwright. Hawthorne, I would argue, has offered in his masterwork an allegory of the Antinomian Controversy, with a point of view contrary to that of his own ancestor.

This historical event may serve Hawthorne for another allegory. After all, the Antinomian Controversy, one of the earliest stories in the history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, concerns a man and woman who are disobedient to authority and therefore expelled. Where have we come upon such a story before . . . ? Patient musing will yield the answer: it is the story of the disobedience of Adam and Eve and their expulsion from Eden. This is the story that Hawthorne wrote about throughout his career, for it conveyed his great themes, original sin (consider, for instance, “Young Goodman Brown” and “The Minister’s Black Veil”) and the possibility of redemption. Arthur, whose initials are A. D., is Adam, and Hester, another name for Esther, is Eve—they represent “the world’s first parents [who] were driven out” (Scarlet Letter, 90). The Scarlet Letter is, I would argue, a double allegory: with the help of The Salem Belle, Hawthorne wrote a historical allegory and a biblical one.

The Salem Belle keenly critiques the fanaticism, the credulity and excess, of Cotton Mather and others. Nonetheless, it is still a conservative book, espousing reliance on the Old Testament and the New Testament and traditional Christian faith. But The Scarlet Letter is no book of piety. Clearly Hester Prynne and Arthur Dimmesdale are sympathetic characters who have defied Puritan conventions; like Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright, they are subversive. Hester herself became a progressive thinker. Still, the Antinomian Controversy intimates the story of Adam and Eve. And though “the world’s first parents” are also subversive in defying God, their story is foundational for any Calvinistic view since it tells of original sin. Indeed, it was a critical part of the Westminster Catechism, which was so central to Puritan teaching. In view of the link of The Scarlet Letter, by way of The Salem Belle, to both the Antinomian Controversy and, ultimately, the Fall (whether Fortunate or not), we may recognize anew the ambiguity that Hawthorne conveyed, the blend of the subversive and the conservative that he offered.

Some have claimed that the study of sources is mere antiquarian indulgence. Yet a source may be so significant for critical interpretation of a work that its identification and appreciation is essential. The Salem Belle is not just a source for a classic but also, in its valuably aiding our reading, a classic source. Perhaps as long as The Scarlet Letter is read, The Salem Belle will be read, as well, deepening and intensifying our understanding and our pleasure.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.