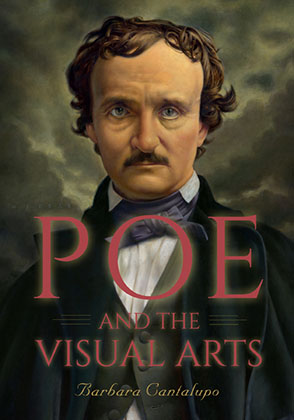

Poe and the Visual Arts

Barbara Cantalupo

“Although Poe’s aesthetics and interest in art have long drawn scholarly attention, Barbara Cantalupo’s Poe and the Visual Arts is the first study to approach the subject comprehensively. She convincingly re-creates the art world in which Poe moved in the 1830s and 1840s, and her deep research reveals Poe’s exposure to and knowledge of a wide gallery of artists and paintings; more important, she illuminates how this engagement affected his own art criticism and his use of art in stories such as ‘Ligeia,’ ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ ‘Landor’s Cottage,’ and many others. Poe and the Visual Arts tackles an exciting topic, and Cantalupo’s firm grasp of it results in a notable contribution to the study of Poe and nineteenth-century American culture.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Although Poe’s aesthetics and interest in art have long drawn scholarly attention, Barbara Cantalupo’s Poe and the Visual Arts is the first study to approach the subject comprehensively. She convincingly re-creates the art world in which Poe moved in the 1830s and 1840s, and her deep research reveals Poe’s exposure to and knowledge of a wide gallery of artists and paintings; more important, she illuminates how this engagement affected his own art criticism and his use of art in stories such as ‘Ligeia,’ ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ ‘Landor’s Cottage,’ and many others. Poe and the Visual Arts tackles an exciting topic, and Cantalupo’s firm grasp of it results in a notable contribution to the study of Poe and nineteenth-century American culture.”

“Barbara Cantalupo’s admirable study enlarges our sense of Poe, reminding us that the creator of the dreadful House of Usher was also an appreciative critic of painting, and even of gardens and domestic decor. We are led to see Poe as a discriminating lover of beauty in general, and we discover both a greater balance and a richer variety in his literary enterprise.”

“This study intelligently and comprehensively examines Poe's unique position in the artistic coteries of Philadelphia and Manhattan, where he worked as an editor. Barbara Cantalupo offers a fascinating overview of the paintings and other artworks shown in galleries and art institutions in those cities—works Poe likely viewed and studied. Cantalupo persuasively demonstrates that Poe was an informed and articulate proponent of beauty in its manifold forms, including the beauty embodied in painting. He was, in short, a perceptive and subtle analyst of the visual culture of his time.”

“Poe and the Visual Arts is an essential addition to the scholarly understanding of Poe’s visual acuity, both in his references to art that enhance the meaning of his stories and in his use of the act of seeing as a component of plot.”

“A superior contribution to Poe scholarship and one of this year’s best books in American literature. . . . Poe and the Visual Arts, impressive in both argument and appearance, belongs on the shelf of every Poe scholar.”

“Paints a very detailed picture of the art-world in Poe’s time, providing the reader with a rich background against which many of the tales are revisited.”

Barbara Cantalupo is Associate Professor of English at Penn State Lehigh Valley and editor of The Edgar Allan Poe Review.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Note on the Text

Introduction

1 Poe’s Exposure to Art Exhibited in Philadelphia and Manhattan, 1838–1845

2 Artists and Artwork in Poe’s Short Stories and Sketches

3 Poe’s Homely Interiors

4 Poe’s Visual Tricks

5 Poe’s Art Criticism

Appendix

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Although Edgar Allan Poe’s name is most often identified with stories of horror and fear, Poe and the Visual Arts stakes a claim for the less familiar Poe—the one who often goes unrecognized or forgotten—the Poe whose early love of beauty was a strong and enduring draw, who “from childhood’s hour . . . [had] not seen / As others saw—.” The evidence in this book demonstrates that Poe’s “deep worship of all beauty,” expressed in an 1829 letter to John Neal when Poe was just twenty, never entirely faded, despite the demands of his commercial writing and editorial career. In that letter, Poe appealed to Neal “as a man that loves the same beauty which I adore—the beauty of the natural blue sky and the sunshiny earth.” Poe and the Visual Arts looks at Poe’s connection to such visual beauty, his commitment to “graphicality” (a word he coined), and his knowledge of the visual arts, noting what he saw, how he used what he saw, and how he criticized those who would not see.

Poe valued the artist’s vision as well as the ability of a writer to create in words what can be seen by “an artistical eye.” His regard for the artist’s ability to see how various, seemingly arbitrary combinations can create a composition of beauty is clearly articulated in “The Landscape Garden”: “No such combinations of scenery exist in Nature as the painter of genius has in his power to produce. No such Paradises are to be found in reality as have glowed upon the canvass of Claude. In the most enchanting of natural landscapes, there will always be found a defect or an excess. . . . [The artist] positively knows, that such and such apparently arbitrary arrangements of matter, or form, constitute, and alone constitute, the true Beauty” (Tales, 1:707–8). The explicit references to paintings and painters, such as Claude, in many of Poe’s stories and sketches enhance thematic concerns or help produce a preconceived effect. In other works, such as “Landor’s Cottage” and “A Tale of the Ragged Mountains,” Poe obliquely refers to the Hudson River school painters by evoking their paintings in his own descriptive prose rather than directly naming the paintings he has in mind. In this way, the tales signal a turn in Poe’s visual aesthetics from the sublime to the beautiful. In addition, Poe’s concern with literary process—as evidenced in “The Philosophy of Composition” and “The Poetic Principle,” for example, as well as in many of his (often harsh) reviews of poetry and fiction—reflects his astute awareness of the similarity between the writing and painting processes. He was keenly aware of how a painter uses his medium to produce a “startling effect,” a concept essential to Poe’s storytelling.

This affinity is evidenced in his February 1838 Southern Literary Messenger review of Alexander Slidell’s The American in England. Poe applauds Slidell’s book as being wise by virtue of being superficial and justifies this seeming contradiction by arguing that the “depth of an argument is not, necessarily, its wisdom—this depth lying where Truth is sought more often than where she is found.” Poe then compares Slidell’s literary effort with the painterly process by observing, “The touches of a painting which, to minute inspection, are ‘confusion worse confounded’ will not fail to start boldly out to the cursory glance of a connoisseur.” In noting that the overall effect of a painting (as seen by a “connoisseur”) overrides the minute, seemingly “confused” strokes that produce that effect, Poe one again affirms his belief that truth often lies on the surface. He states this quite clearly in his “Letter to B–––”: “As regards the greater truths, men oftener err by seeking them at the bottom than at the top.” In his review of Slidell’s work, Poe also foregrounds his understanding of how a painter creates illusion and how that process applies to literary technique. For example, he compares Slidell’s literary finesse with painterly technique as follows: “[Mr. Slidell] has felt that the apparent, not the real, is the province of a painter—and that to give (speaking technically) the idea of any desired object, the toning down, or the utter neglect of certain portions of that object is absolutely necessary to the proper bringing out of other portions—portions by whose sole instrumentality the idea of the object is afforded.”

Three years later, Poe reiterated this understanding in a May 1841 Graham’s Magazine review of Charles Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop, and Other Tales. Here Poe points out that a painter, rather than attempting to create a direct duplicate of the subject to be depicted, uses his medium to communicate its truth to the viewer through the manipulation of brush stroke, light, composition, line, and shadow—exaggerating elements when necessary and diminishing others to create the desired effect. As he explains, “No critical principle is more firmly based in reason than that a certain amount of exaggeration is essential in the proper depicting of truth itself. We do not paint an object to be true, but to appear true to the beholder. Were we to copy nature with accuracy the object copied would seem unnatural.”

In 1845, in Marginalia 243, Poe once again returned to his long-standing idea that the “mere imitation, however accurate, of what is in Nature, entitles no man to the sacred name of ‘Artist.’” As noted in “The Landscape Garden” and “The Domain of Arnheim,” Poe strongly believed that transformation, combination, and composition create beauty beyond what nature can produce, and this belief is evident in the marginalia entry: “We can, at any time, double the true beauty of an actual landscape by half closing our eyes as we look at it. The naked Senses sometimes see too little—but then always they see too much.” In this short piece, Poe also provides a definition of “Art”: “Were I called upon to define, very briefly, the term ‘Art,’ I should call it ‘the reproduction of what the Senses perceive in Nature through the veil of the soul.’”

Often, too, Poe used visual metaphors as high praise. For example, in his September 1839 Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine review of Friedrich Fouqué’s Undine, Poe overwhelmingly praises his writing: “‘Undine’ is a model of models, in regard to the high artistical talent which it evinces. We could write volumes in a detailed commentary upon its various beauties in this respect. Its unity is absolute—its keeping unbroken. Yet every minute point of the picture fills and satisfies the eye” (Works, 10:37). Furthermore, in his February 1836 “Autography,” Poe applauds John P. Kennedy’s handwriting: “This is our beau ideal of penmanship. Its prevailing character is picturesque. . . . We should suppose Mr. Kennedy to have the eye of a painter, more especially in regard to the picturesque” (Tales, 1:273). Poe’s praise for the painterly process and for visual art was consistent throughout his literary career.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.