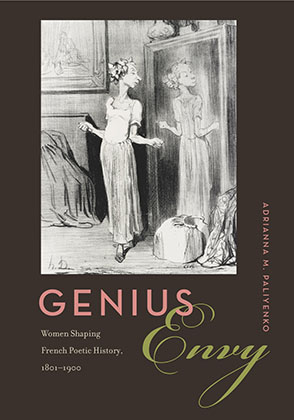

Genius Envy

Women Shaping French Poetic History, 1801–1900

Adrianna M. Paliyenko

“This is a valuable book that will become a significant point of reference. Along with studies like Margaret Cohen’s Sentimental Education of the Novel, it makes a major contribution to our understanding of the cultural context in which women were writing. . . . Paliyenko has opened up new horizons, and this book will certainly invite, provoke, and make possible further work in an important field.”

- Unlocked

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

An Open Access edition of Genius Envy is available through PSU Press Unlocked. To access this free electronic edition click here. Print editions are also available.

This fresh account of French women poets’ contributions to literature probes the history of their critical reception. The result is an encounter with the texts of celebrated writers such as Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, Anaïs Ségalas, Malvina Blanchecotte, Louisa Siefert, and Louise Ackermann. Glimpses at the different stages of each poet’s career show that these women explicitly challenged the notion of genius as gender specific, thus advocating for their rightful place in the canon.

A prodigious contribution to studies of nineteenth-century French poetry, Paliyenko’s book reexamines the reception of poetry by women within and beyond its original context. This balanced and comprehensive treatment of their work uncovers the multiple ways in which women poets sought to define their place in history.

“This is a valuable book that will become a significant point of reference. Along with studies like Margaret Cohen’s Sentimental Education of the Novel, it makes a major contribution to our understanding of the cultural context in which women were writing. . . . Paliyenko has opened up new horizons, and this book will certainly invite, provoke, and make possible further work in an important field.”

“Adrianna Paliyenko brings to her work on French women’s poetry an already most impressive background, and she writes with authority and solid, yet graceful, erudition. Genius Envy will attract and inform many readers, male and female—especially at a time when nouns like auteur(e) and écrivain(e) are asserting their presence in the language—and will undoubtedly become a long-lasting milestone in the burgeoning study of French women poets.”

“Adrianna Paliyenko’s major new assessment of poetry composed or theorized by women, Genius Envy, is long overdue in professional nineteenth-century French studies circles. Her incisive reexamination of this undervalued literary corpus and recent scholarship about it puts to rest for good the myth that female poets—contemporaries of Lamartine, Hugo, Gautier, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Mallarmé—were somehow less aesthetically significant than more widely celebrated male writers.”

“The fruit of more than a decade of research, Genius Envy radically upends current thinking about women poets, their reception, and their engagement with the allegedly male-dominated world of nineteenth-century French literature. Evoking a multiplicity of female voices and touching on colonial history, social class, philosophy, science, and aesthetics, Adrianna Paliyenko’s remarkable new book is required reading for those interested in genius, the history of canon formation, and literary and social equity.”

“Genius Envy makes a major contribution to studies of nineteenth-century French poetry. Adrianna Paliyenko’s treatment of women writers who challenge the previously male-defined notion of genius reframes much more than the study of these five writers; it cuts through stale definitions of writers as masculine or feminine and argues convincingly for a new way of considering genius, creativity, and the poetic. As a result, it raises important questions about women’s place in discourse, important today as it was then.”

“After centuries during which genius was defined as exclusively male, Adrianna Paliyenko provides a brilliant, learned, and highly readable account of the extremes to which men went in order to deny genius to women. With equal brilliance she restores several pages excised from nineteenth-century literary history by this gendering, and she gives voice to French women poets as they challenge their exclusion. Thanks to Paliyenko’s groundbreaking book, the sexing of genius has lost its self-evidence, and the nineteenth century has gained five major poets.”

Adrianna M. Paliyenko is Charles A. Dana Professor of French at Colby College. Her most recent book, coedited with Joseph Acquisto and Catherine Witt, is Poets as Readers in Nineteenth-Century France.

Introduction

“Sire, le premier poète de votre règne est une femme: Madame Valmore.” This statement recalls a woman who rose from the ranks of the working class to become a leading poet in the 1820s, preserving a foundational chapter in the other history of nineteenth-century French poetry. But why have literary historians passed over all other women in establishing the official literary canon? Only Desbordes-Valmore’s verse and prose have gained a prominent place on library shelves as well as in critics’ discussion of the Romantic era. Are we to imagine that, apart from her, no other woman contributed to arguably the most fertile century of poetic production in France? What does Desbordes-Valmore’s privileged position as a sentimental genius tell us about her legacy, which buries other poetic women? Traditional accounts of literary history offer vastly different answers to these questions than does the reception of individual women’s poetry, which underscores the aesthetic force of their rich body of work across the century. Such disparate views of the French poetic past generate the core query pursued in this book. How did women’s diverse poetic achievements survive a history that excluded them?

Central to understanding how the narrative of reception obscured yet recorded the women who shaped the history of poetry in nineteenth-century France is the debate about the sexing of genius, which crystallized among Enlightenment thinkers. This debate highlighted the drive to locate the source of genius. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who derived the force of the mind from the muscles, claimed that a work of genius was beyond women’s reach: “Les femmes, en général, n’aiment aucun art, ne se connaissent à aucun et n’ont aucun génie” (Lettre à d’Alembert, 138). In De l’esprit (1758), his contemporary Claude Adrien Helvétius in turn deliberated whether the superior mind was a gift of nature or bequeathed by nurture, concluding that “l’homme de génie n’est donc que le produit des circonstances dans lesquelles cet homme s’est trouvé” (180). For this thinker, who considered the mind equal in all individuals from birth, intellectual inequality resulted from education and application. Later, by way of response to Rousseau’s Émile; ou, De l’éducation (1762), in the posthumous work De l’homme: De ses facultés intellectuelles et de son éducation (1772), Helvétius considered the relation of gender and brain power: “L’organisation des deux sexes est, sans doute, très différente à certains égards: mais cette différence doit-elle être regardée comme la cause de l’infériorité de l’esprit des femmes?” (1:153). He responded that a lack of access to education, not innate inferiority, explained the absence of women from the historical record of superior achievements across the disciplines. In Lettres d’un bourgeois de New Haven à un citoyen de Virginie (1787), the marquis de Condorcet (known as Nicolas de Caritat) shared Helvétius’s ultimate position on why the past had yielded so few women of literary or scientific genius: “De plus, l’espèce de contrainte où les opinions relatives aux mœurs tiennent l’âme et l’esprit des femmes presque dès l’enfance, et surtout depuis le moment où le génie commence à se développer, doit nuire à ses progrès dans presque tous les genres. . . . D’ailleurs, est-il bien sûr qu’aucune femme n’a montré du génie?” (19). The question Condorcet put to history frames the polemic that would surround genius throughout the nineteenth century and imbue the critical reception with ambiguities. If now defined by leading thinkers of the day as an aptitude and linked with superior creativity as well as intellectual power, was genius innate, acquired, or both?

Through the struggle over the meaning of “génie,” nineteenth-century writers revealed the stakes of the quest by science to discover the origins of genius and thus determine who could access its property. Representative of those who ignored the impetus to reexamine genius in relation to sex is Arthur Schopenhauer in “Of Women” (1851). Schopenhauer invoked Rousseau to reiterate, “Neither for music, nor for poetry, nor for fine art, have [women] really and truly any sense or susceptibility; it is a mere mockery if they make a pretense of it in order to assist their endeavor to please” (Works, 451–52). Biology, asserted Schopenhauer, reinforced the view that women had never produced “a single achievement in the fine arts that is really great, genuine and original; or given to the world any work of permanent value in any sphere” (452). He argued that being male was the fundamental condition of genius, even though medical science offered no such proof. Schopenhauer’s deeper narrative of exceptional creativity prefigured a Freudian analysis of female psychology. Because the work of genius was said to preclude femininity, conservative readers equated women’s creative ambitions with so-called phallic envy. As expressed in Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt’s Les hommes de lettres (1860), “Le génie est mâle. . . . Une femme de génie est un homme” (176). From the perspective of the dominant genius discourse in nineteenth-century France, women could not create the “great works” later selected for the French literary canon.

And yet, the history of the word “genius” does not privilege a sex. Originally, the word referred to the spirit associated with a person at birth, which the Greeks called a daimōn and the Romans a “genius.” In the classical sense derived from the ancient view, genius signified a divinely inspired gift that moved the seer, or the vates, synonymous with poet, to reveal the unknown. Enlightenment thought maintained a mimetic tradition, but sharpened the notion of genius in relation to the superior application of aesthetic rules. The term “originalité,” which the Romantics would use to recognize artistic invention or scientific discovery, simultaneously emerged as a separate category. As Roland Mortier observes about this development in France during the latter decades of the eighteenth century, the adjective “original,” synonymous with unique, did not carry over to the noun “un original,” a person considered “bizarre,” “excentrique,” or “ridicule” (L’originalité, 32). The link made in French between génie (from the Latin genius) and creation stemmed from another etymology that allowed generative power to become part of the equation.

In De l’esprit (1758), Helvétius argued that the metaphors used to signify genius, “un feu, une inspiration, un enthousiasme divin,” failed to distinguish invention, which derives from the root gignere, “to beget or produce,” as its principal quality (475). Defined as “making” or “discovering,” invention accounted for poetic and scientific genius, respectively. Rejecting the belief that genius was “un don de Nature,” bestowed upon a select few, he claimed that genius was common. The circumstances needed to produce genius, however, were rare. Its manifestation required learning and work, as he elaborated in De l’homme: “Le génie, selon nous, ne peut être que le produit d’une attention forte et concentrée dans un art ou une science” (1:31). Helvétius understood genius as the result of a process, intuiting a synergy between genes and the environment suggestive of modern-day epigenetics. In redefining genius, rather than describing its effect or attempting to situate it, he uncovered physiology as a factor without, however, making one sex the sole originator.

Throughout the nineteenth century, metaphysical accounts of exceptional creativity competed with pseudoscientific explanations. Claims about the source of genius thus shifted between the mind and the body, unwittingly revealing why the attempts to locate the origins of a process inextricably linked to its product, to the creative work itself, would inevitably fail. Early French Romantics gendered the classical view of divine inspiration, locating its effect in men’s heads versus women’s hearts. With a turn to the Latin ingenium (innate ability) and a procreative twist on gignere, medical philosophers pulled genius further down into the body, making the male seed, thought to govern human reproduction, its source. This physiology remained undisturbed well beyond the century. Even though embryology’s progress accounted for equal female contributions to reproduction, the analogy of male procreativity and cultural production undergirded the collective reception of women as poètes manqués.

Women writers’ surge overlapped with that of Romanticism in the 1820s, garnering mixed reviews. Although the individual poets among them captivated amateur and elite readers alike, their strength in numbers raised concern, with the sentimental novel also stiffening competition in the market. By then, the notion of “original genius” had taken hold. Imaginative power, associated with spontaneity and authenticity, supplanted the classical tradition of mimesis, or imitation, of the ancients. The meaning of genius developed separately from talent, not in the dictionary, but as a category for distinguishing men’s creations from women’s. Yet, as late as 1869, in attempting to prove that genius was a male inheritance, Francis Galton exposed the lack of consensus about “the definition of the word” as a serious difficulty “in the way of discovering whether genius is, or is not, correlated with infertility” (Hereditary Genius, 330).

In defining “genius” for his dictionary, Émile Littré retained its dual etymology (genius and gignere) along with the dispute over its origins and makeup. In describing génie as inherent, Littré called it a “talent naturel extraordinaire” (1151, 1152). By “talent” he meant a special aptitude, but added that it was either a gift or acquired by work: “aptitude distinguée, capacité . . . donnée par la nature ou acquise par le travail” (2134–35). Herein lies the conceptual way that nineteenth-century women gradually disentangled from sex: by reformulating poetic originality as the work of genius, the process made manifest by the creation that always takes us by surprise. In thinking through their poetry and its reception, women conveyed the depth of ideas with which they engaged to shape for posterity their rightful place in French poetic history.

Reading Women Back into Poetic History

In the absence of modern editions of complete poetic works by most women writers of the nineteenth century, except for Desbordes-Valmore, anthologies such as those by Alphonse Séché (1908–9), Jeanine Moulin (1966, 1975), Christine Planté (1998), and Norman Shapiro (2008) have filled many gaps in the record. Though these collections differ in critical apparatus and selection, they suggest how widely French women’s writing ranges aesthetically, thematically, and ideologically across the centuries. The nineteenth century exemplifies such diversity, which complicates the traditional ascription of gender to poetry in Wendy Greenberg’s 1999 Uncanonical Women: Feminine Voice in French Poetry. From a feminist vantage, in The Gendered Lyric: Subjectivity and Difference in Nineteenth-Century French Poetry (1999), Gretchen Schultz juxtaposes men’s and women’s poetry to show the aesthetic axis along which this division was historically constructed. As Alison Finch observes in a critical survey of nineteenth-century women authors, many of these writers argued against gender stereotyping. Genius Envy delves into poetic women’s contestatory work, in particular, to shed light on the original ways that women inscribed themselves in literary history, not as “women poets” or “poetesses,” but as poets.

To expose the problem of gender as a category of literary analysis, this book shows how poetic women experimented with form and content while gravitating toward a multiplicity of voices. Probing and innovative, women’s production unfolds as a critical dialogue, not only as a conversation between poets and their readers but also as a revisionist discourse on genius. Within the context of the “discursive combat,” or symbolic resistance, in nineteenth-century France, theorized by Richard Terdiman, women seeking expression as poets engaged as much with the gendered discourses that constituted the canons of criticism as with the history of ideas in making their work the counterdiscourse (Discourse/Counter-Discourse, 43). The richness of women’s achievements as poets emerges from this exchange, their work resisting and thus texturing its reception.

Genius Envy begins by reconstructing the history of reception that obscured the scope of women’s poetic projects in an era celebrated for aesthetic innovation. In part 1, the chronological organization foregrounds how three principal discourses overlapped in rival assessments of women as poets that linked genius, envy, and femininity. This critical nexus draws sex into the appraisal of women’s poetry. When fused with the female body, verse flows directly from the heart. Judged as natural but artless, such effusion precludes the brainy stuff of genius. Relegated to a separate category, “women poets” cannot compete with men. Yet, those women recognized as creators destabilize this narrative of the past. Part 2 presents five distinct trajectories forged by women of different generations: Anaïs Ségalas, Malvina Blanchecotte, Louisa Siefert, Louise Ackermann, and Marie Krysinska. Modern readers encounter the unfolding of each poet’s work in its original context and thus can follow the stages of its reception.

Primary and secondary sources—including anthologies, pedagogical manuals, magazines, newspapers, correspondence, and medical treatises—constitute this book’s twofold corpus: the critical literature and the creative body. Women galvanized the genius debate in the nineteenth century, testing the history of an idea. In chapter 1, I consider to what extent women who aspired to be remembered as poets disputed the physiology of exceptional creativity, joining those who proclaimed that genius has no sex. Critics consistently attest to the upsurge of women writers in the opening decades of the nineteenth century, but not to the record number of poets among them. What is especially striking about the upsurge of women writers in the nineteenth century is that they represented all classes. French names reveal class; for example, the “de” in Madame de Staël indicates noble rank. Virtually none of the women acclaimed as poets published under male pseudonyms. Though Blanchecotte and Ackermann first used initials, they subsequently signed their full names. Given that they hailed from the working class and the bourgeoisie, respectively, this gesture had more to do with gender than with class and the increasingly hostile environment literary women faced, especially those wanting to preempt being associated with the narrow category of “la poésie féminine.”

The mapping of the narrative of literary reception in chapter 2 highlights two major backlashes, in the 1840s and 1870s, which elucidated the critical trend to read women as poètes manqués. Yet the semantic drift of the categories used to widen the gap between femininity and creativity reveals the struggle to control the inheritance of genius by passing on a separate “woman’s tradition.” This paradigm, drawn from a conservative reading of Desbordes-Valmore as the quintessential “woman poet,” the mater dolorosa, does not account for the various ways that women entered the field across the century. In chapter 3, I examine the different strategies women used to develop poetic agency, beginning with those who came on the scene with Desbordes-Valmore. The sororal network she created with Amable Tastu and Mélanie Waldor did not extend to Élisa Mercœur, Ségalas, and Louise Colet. But, like Desbordes-Valmore, each of these poets forged a distinct creative identity, reconciling femininity with creativity to varying degrees. Women’s diverse projects along with their reflections on aesthetics show that even those poets who wrestled explicitly with being placed in Valmore’s shadow in the latter part of the century struggled more with the gendering of originality.

Marked differences in form, voice, and vision demonstrate the diversity and multiplicity of women poets throughout the century. In chapter 4, I treat Ségalas’s response to France’s colonial enterprise during the nineteenth century in order to restore part of her intellectual legacy. From 1831 to 1885, the Parisian writer with Creole roots engaged the century’s debate on abolition along with the emergence of scientific racism. The self-styled worker and poet Blanchecotte launched her career in 1855, probing the notion of genius in relation to class and gender. Her project, addressed in chapter 5, exploits the in-between to associate creative production with work. Louisa Siefert, from the literary elite in Lyon, blurred aesthetic categories in works from 1868 to 1881 by expressing pain, yet viewing it with philosophical objectivity. Examined in chapter 6, Siefert’s treatment of the mind-body split elicits the dialogic nature of poetic voice, revealing the creative power of the other in the “I.” The erudite Ackermann, the subject of chapter 7, considered poetry a science or a way of knowing. In fusing passion with reason, she positioned her voice between poetic writing and thinking. The Polish-born Krysinska, presented in chapter 8, took an interdisciplinary approach to the work of originality in fin-de-siècle Paris. In reconsidering the origins of poetry to write the history of her own vers libre, Krysinska revised the biblical creation story and disputed evolutionary science to theorize genius in the work itself.

Nineteenth-century poets who happened to be born women progressively laid claim to the property of genius on their own terms as they untangled their voices from the sentimental writing that, for conservative critics, embodied the “woman’s tradition.” From the start of the century, women embedded reflections on genius in their verse. They intervened as critical readers of their writing and its reception with increasing confidence, amplifying their poetic output with prefaces. Other paratexts, including correspondence with fellow poets, mentors, and critics, as well as essays and prose collections, illuminate how deeply women examined the centrality of gender in creativity.

The poets featured in Genius Envy represent salient ways in which women have broken the so-called feminine mold, imaginatively and conceptually. Their hybrid production, spanning the century, forms a discursive site that resists inherited meanings of genius. Women’s thinking through poetry and beyond, as shown in the chapters that follow, provides new canons of criticism for recovering the meaning of their work and the history of ideas about genius it illumines.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.