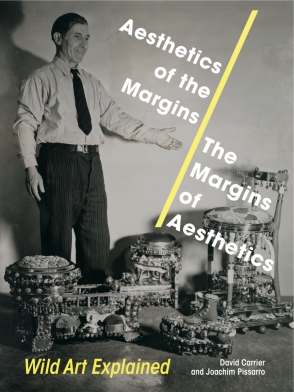

Aesthetics of the Margins / The Margins of Aesthetics

Wild Art Explained

David Carrier and Joachim Pissarro

Aesthetics of the Margins / The Margins of Aesthetics

Wild Art Explained

David Carrier and Joachim Pissarro

“Their recurring focus on Kant’s “antimony of taste,” an evaluation of aesthetic experience as individually unique but also paradoxically anchored to a hope for universal assent, has major implications for the calls for canon revision and new initiatives around diversity and inclusion that presently consume all corners of the “system.””

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Arguing that both the “art world” and “wild art” have the same capacity to produce aesthetic joy, Carrier and Pissarro contend that watching skateboarders perform Christ Air, for example, produces the same sublime experience in one audience that another enjoys while taking in a ballet; therefore, both mediums deserve careful reconsideration. In making their case, the two provide a history of the institutionalization of “taste” in Western thought, point to missed opportunities for its democratization in the past, and demonstrate how the recognition and acceptance of “wild art” in the present will radically transform our understanding of contemporary visual art in the future.

Provocative and optimistic, Aesthetics of the Margins / The Margins of Aesthetics rejects the concept of “kitsch” and the high/low art binary, ultimately challenging the art world to become a larger and more inclusive place.

“Their recurring focus on Kant’s “antimony of taste,” an evaluation of aesthetic experience as individually unique but also paradoxically anchored to a hope for universal assent, has major implications for the calls for canon revision and new initiatives around diversity and inclusion that presently consume all corners of the “system.””

“Carrier and Pissarro present a refreshing argument for aesthetic openness, for the benefit of considering things alien to our social and cultural indoctrination. Their provocative account of the shifting division between the Art World and Wild Art avoids resorting to cultural scandal or moral failure to propel its narrative. The authors merely point out that all cultures—others as well as ours—are exclusionary. Without claiming to rid us of our habits of exclusion, the authors aim to undermine the binary barriers to appreciating aesthetic value: good, bad; high, low; popular, elite. Theirs is a hard-headed, level-headed corrective to politicized accounts that pit one form of aesthetic practice against another.”

David Carrier retired as Champney Family Professor, a post divided between Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Art. He previously had been Professor of Philosophy at Carnegie Mellon University. His numerous publications include A World Art History and Its Objects, The Aesthetics of Comics, Principles of Art History Writing, all also published by Penn State University Press, as well as Aesthetic Theory, Abstract Art, and Lawrence Carroll.

Joachim Pissarro is an art historian, theoretician, and the Bershad Professor of Art History and Director of the Hunter College Art Galleries. He previously served as curator at The Museum of Modern Art and the Yale University Art Gallery. His publication and curatorial projects include Cézanne/Pissarro, Johns/Rauschenberg: Comparative Studies on Intersubjectivity in Modern Art; Jeff Koons: The Painter and the Sculptor; Martin Creed: What’s the Point of It?; Joseph Beuys: Set Between One and All; and Notations: The Cage Effect Today.

Contents

List of IllustrationsAcknowledgmentsIntroduction1. Modern Foundations of the Art World2. The Classical Model: Dogmatism and Alternative Models of Looking3. Dawn of Modernity4. The Wise, the Ignorant, and the Possibility of an Art World that Transcends This Divide5. The Antinomy of Taste and Its Solution: Variations on a Theme by Duchamp6. The Museum Era7. Institution of Art History8. Art Beyond the Boundaries of the Art World9. The Fluid Nature of Aesthetic Judgments10. Kitsch, a Nonconcept: A Genealogy of the IndesignatableConclusionNotesSelected BibliographyIndex

From the Introduction

“There was a time when I . . . despised the common people, who are ignorant of everything. It was Rousseau who disabused me. This illusory superiority vanished, and I have learned to honor men.“—Immanuel Kant, Gesammelte Schriften, 20:44“Let’s drop those exclusive shows that depressingly keep a small number of folks in a dark space, holding them tight and intimidated, in total silence and inaction. . . . No, happy folks, these entertainments are not for you! Go outside, gather in the open air, and under the sky: and there, indulge yourselves, and let the sweet feeling of your happiness take over. . . . Let your own senses of pleasure be free and generous, just like you; let the sun shed light on your free and innocent shows; you yourselves will produce one of these shows. . . .

But what will be the contents of these shows? What will be shown there? Nothing, if you will. With liberty in the air, with abundant flows of people everywhere, a sense of wellbeing will overtake everyone. As for contents: just stick a pole there, in the middle of an open space, and garnish it with a crown of flowers at the top, bring the people there, and you will have a show and a party! Go further even: make the audience become part of the show: turn them into players themselves; make everyone see and love oneself in each other, so that they will be even more tightly united than ever.”

—Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Lettre à d’Alembert sur les spectacles; emphasis added

In our book Wild Art, we made a somewhat terse distinction between works of art that are praised, discussed, evaluated, and interpreted within what we called the Art System (the museum, the art trade, and the academy) and what we called Wild Art (i.e., all forms of art that conspicuously seemed to remain outside the confines of the Art System—graffiti, tattoos, sand constructions, ice art, and all kinds of artistic expressions that we thought would be unlikely to ever permeate the rather rigid barriers of the Art System). That book was primarily devoted to presenting examples of Wild Art, as well as our attempt to outline some of the conceptual or ideological premises of these works.Our initial project comprised two parts. The first part mapped out some of the broad families of artistic objects that stand outside the Art System, while the second part addressed the historical, philosophical, political, and ethical underpinnings that have served as the foundation of a split art world—one, the Art System, having achieved full legitimacy; the other, Wild Art, having mostly been ignored by the Art System but happily functioning without any apparent need for legitimation by that system. That book and this one complement each other, for it is necessary to have a historical and theoretical framework in order to understand our examples, and the examples are required in order to take the full measure of our claims. We now present a full philosophical and historical analysis that defends and develops our way of thinking. This is a self-sufficient volume, but interested readers may find it valuable to consult Wild Art.

We began our project with the observation that there are two kinds of art: Art World art, which is found, valued, and interpreted within the Art System, and Wild Art, which for the most part is found outside of that Art World. We model this divide on two distinctions found in the organic world: that between domestic (or tame) animals and wild animals, and that between domestic plants and wild vegetation. Think of an orchid versus couch grass: one requires high maintenance and frequent watering, and the other grows anywhere, in all environments, requiring no special care.

Such distinctions do not equate to value judgments. There is plenty of mediocrity in both worlds, and there is also plenty of great art and fascinating forms in both the Art World and Wild Art. Our definition of Wild Art is topical, or descriptive, not evaluative (although at times both, or each, of us may cast a value judgment when we feel it is pertinent to the argument). Initially, our purpose was to map out a field that was little studied within the Art System. What we are saying, however, is that any value judgment solely based on whether a work of art belongs to this field or that field is inept. In other words, neither field (the Art World or Wild Art) inherently possesses the exclusive criteria of good art or bad art.Throughout the modern era, art critics and historians have mostly focused on art made within or for the Art World. But once one discovers that there are really several kinds of art, one understands the Art World differently. We favor writing Art World, Art System, Art History, and Wild Art with capitals, in order to point to these entities as homogeneous concepts (in a Hegelian mode of expression), which we later critique through a more Kant-influenced model. We suggest that teleological, axiological, and historicist systems of values (largely the legacy of various intonations of Hegelian discourses) have become cumbersome and obsolete and foreclose our visual and intellectual horizons. What we propose is not to confer the same value (or the same grade) on all forms of art (far from it!) but to openly consider the claim to validity of numerous art forms that have never seen the light of day within the Art System. That is all.Our approach to the Art World was sourced largely from three directions: Kant’s aesthetic theory, a consideration of the origin and development of the art museum in Europe and the United States from the late eighteenth century through to the advent and ascension of modernism, and a historiographic approach to Art History in order to highlight the “silences” of the field. Given the volumes of references involved in each of these areas, we have decided to cite only those few publications that are of immediate relevance to our analysis.Our Western cultures are based—from nursery school onward—on the need to stress and develop in all children their creative capacities. There is, at the foundation of our culture, a profound shared need to develop creative instincts in all children. There are, however, paradoxes within this. The first is that while every child is encouraged to develop her inner skills and talents in order to affirm her individuality—her originality—the system of cultural validation (mainly through the museum system) excludes rather than includes. The strange and paradoxical dynamics of the education systems (from kindergarten through high school) go like this: we start with the kindergarten system of universal encouragement of creativity in all children, and we end in twelfth grade with a small minority of students still exposed to the arts. Few people dare critique this state of affairs. Agnes Gund, former chair of the board of MoMA and the founder of Studio in a School, a nonprofit organization that facilitates and supports continuous development of art education in New York public schools, summed up the situation: “Schools need to understand that [teaching art] is as important to children as having math or English lessons, because it gives them a dimension—it allows them to star in something that they might not have otherwise.”The Art World, just like the art education system, is based on layers of filters and selectivity, promoting criteria of exclusion rather than inclusion. What is noteworthy is that this system of exclusion, or selectivity, does not just exist as Art World versus any form of art outside the Art World. It is also present within the fabric of the Art World proper, in the form of mini-systems of mutual exclusion. It is as though the Art World might barely exist without these systems of exclusion. It is interesting to hear the voice of one of the leading contributors to October, an institution that itself has often been targeted for its lack of inclusivity. According to Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, the Art World depends upon policing by specialists. Preserving modernism, Buchloh argues, requires their intervention. “What is aesthetically achievable is not in the control of critics, or historians or even artists, unless artistic practice is to become a mere preserve, a space of self-protection.” Everywhere, throughout the cultural world, one finds zones of exclusion (what Buchloh refers to as spaces of self-protection), which employ criteria of acceptance and refusal that largely reflect the sympathies and fears of the agents of culture. Contrary to what one might imagine, these terms of exclusion are not the sole preserve of the Western world; they are not just the signature of so-called bourgeois society, either. These criteria of exclusion, in fact, appear to be ubiquitous in every art and cultural sphere.In order to highlight the peculiarity of this situation within the Art System, let us briefly turn to lexicography and to the possibilities offered by language to create an aesthetic situation out of word games through twists, puns, and slang. Specifically, let us look at what the Soviet regime and official culture did to the Russian language in the U.S.S.R. It is not well known that the Soviet regime attempted to outlaw the use of slang at every level of communication. For decades, “slang was off-limits to dictionaries and no research was conducted in this field.” Censorship barred the use of slang, not only in all official television and media but also in every form of literary production, including magazines and newspapers. Not only was the use of any “street” expressions or idioms forbidden, but no linguistic or lexicographic scholarly research was allowed in the field of colloquial or slang Russian. “The negative attitude of Soviet scholarship toward slang resulted in significant losses for lexicography; many words of ‘low style’ have been lost forever.” Today, of course, countless books, dictionaries, and dissertations have renewed investigations into the fascinating and rich fields of colloquialisms, street language, and slang. This shows that these notions of “preserves of taste,”exclusion systems, and criteria of excellence (to be defended against vulgar forms of expression) are not the appanage of Western capitalist societies. Interestingly enough, both inimical systems—capitalism and communism—have founded their values on vast systems of exclusion. An analogous, and frightening, situation also occurred during the Cultural Revolution in Mao’s China, wherein all systems of taste (left or right, Western or Eastern) were based on criteria of exclusion.What happens if we decide to open up these criteria and look beyond the peripheries of these preserves of taste? Our tasks in the field of art offer a striking parallel to the situation described previously, with the Soviet authorities barring access to and use of certain forms of language. Indeed, as Rousseau mentioned, it is common and easy to despise what is referred to, with some condescension, as forms of expression, cultural manifestations, and artifacts from “the common people”—who essentially do not count within the confines of the established Art World, or, to be more precise, who count only insofar as their foot traffic (and economic impact) validates the decisions made by the policing agents of the Art World.Testing these premises, and having allowed our illusory sense of superiority to vanish, we began to look outside the Art World without feeling that we were drowning in a quagmire of mediocrity, or descending into the infernal abysses of the Society of the Spectacle. It has felt strangely liberating.We could not believe (and still cannot believe) the vast arrays of forms of art that were available to us as we decided to look and keep looking. What we propose to offer is not an encyclopedia of the unquantifiable forms of art that surround us, but rather a critical glimpse into this garden of delights that has been kept at bay from the safely guarded closures of the established Art World. By the same token, we will begin to question the critical and cultural conditions that made this vast exclusion not only possible but, in fact, wholly accepted and so utterly taken for granted that whenever we broach the subject of these millions (if not billions) of art objects that lie outside the gaze of art professionals, we continue to be met with looks of astonishment, if not outright suspicion.[Excerpt ends here.]

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.