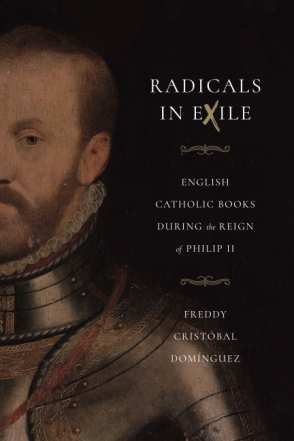

Radicals in Exile

English Catholic Books During the Reign of Philip II

Freddy Cristóbal Domínguez

Radicals in Exile

English Catholic Books During the Reign of Philip II

Freddy Cristóbal Domínguez

“Domínguez has provided a focused, informed, and lively account of the publishing activities of Elizabethan English Catholic exiles—and through these activities the exiles’ deep involvement in Spanish political-ecclesiastical culture—during a critical moment in the history of Anglo-Spanish politics.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Freddy Cristóbal Domínguez looks at English Catholic propaganda within its international and transnational contexts. He examines a range of long-neglected polemical texts, demonstrating their prominence during an important moment of early modern politico-religious strife and exploring the transnational dynamic of early modern polemics and the flexible rhetorical approaches required by exile. He concludes that while these exiles may have lived on the margins, their books were central to early modern Spanish politics and are key to understanding the broader narrative of the Counter-Reformation.

Deeply researched and highly original, Radicals in Exile makes an important contribution to the study of religious exile in early modern Europe. It will be welcomed by historians of early modern Iberian and English politics and religion as well as scholars of book history.

“Domínguez has provided a focused, informed, and lively account of the publishing activities of Elizabethan English Catholic exiles—and through these activities the exiles’ deep involvement in Spanish political-ecclesiastical culture—during a critical moment in the history of Anglo-Spanish politics.”

“Domínguez makes a clear and forceful argument for the impact of Spanish Elizabethan authors on Spanish politics during the final decades of Philip II’s reign. Yet this book achieves something even more significant for those of us looking to the future of early modern studies. It demonstrates the benefits of transnationalism in furthering our understanding of Europe’s religious and political environment.”

“Scholarship on English Catholicism has started to take greater account of its broadly European and international dimensions, and Domínguez makes an important contribution to this line of scholarship. Radicals in Exile presents a convincing case for the central role of English Catholics in late sixteenth-century Spanish and wider European politics. It casts new light on English Catholics’ links with Spain, and future scholarship will no doubt expand on these links, looking at connections beyond the printed word.”

“Freddy Domínguez’s important book expands our knowledge of English and Spanish Catholic print culture beyond immediate confessional considerations to illuminate instead the tangled polemics of secular rule and spiritual authority.”

“Domínguez’s work, with its transnational perspective, rejection of confessional and nationalist narratives, and recovery of marginal voices, contributes positively to encouraging trends in modern Reformation scholarship.”

“Through a meticulous engagement with both English and Spanish works and ideas, Domínguez reminds us that exiles were influenced not only by developments in England, but also by the historical circumstances and ideas present in their adoptive home. Radicals in Exile is a much-needed study, which is sure to make an indelible impact in the field.”

“Domínguez has succeeded in asserting, with great erudition and eloquence, the central importance of books in the intertwined intellectual, political and religious history of England and Spain.”

“Skillfully researched and written with enviable clarity, Freddy Domínguez’s Radicals in Exile explores in detail a series of texts English Catholics wrote from Spain during the dramatic years of the 1580s and ’90s. His readings of these works are original and illuminating, and they integrate this singular corpus into the wider religious and intellectual history of the period.”

“This book puts the punch back into early modern religious polemic. Radical English Catholic exiles deftly bob and weave across the pages with hired-gun Protestant apologists. London swings at Madrid, Madrid jabs back at London, while Rome, Paris, and Antwerp stand by, eager to climb into the ring. The many contenders in this post-Reformation prizefight in print yield refreshingly unfamiliar viewpoints, internecine agendas, and a dynamic polyglot literature that has been too often overlooked.”

Freddy Cristóbal Domínguez is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Arkansas.

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I: History in Action

1. The Radicalization of Exile Polemic

2. Calling the Armada

3. English History Made Spanish

Conclusion to Part I

Part II: The King’s Men

4. English Voices in Spain

5. An Anglo-Spanish Voice in Europe

6 Between “English” Providentialism and Reason of State

Conclusion to Part II

Part III: (Habsburg) England and Spain Reformed

7. Politics of Succession

8. Practical Politics and Christian Reason of State

Conclusion to Part III

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

From the Introduction

Dom Sebastião, king of Portugal, died in a Moroccan desert near Ksar el-Kebir

in 1578. His dream of Christianizing the Maghreb ended in failure, and worse, his death exacerbated troubles within Christendom. Dom Henrique, Sebastião’s uncle—an old, childless cardinal—succeeded him, and in Portugal and across Europe, statesmen waited anxiously for his death and its aftermath. To ward off the vultures, Dom Henrique requested papal permission to marry in the frail hope of producing an heir. He never wed and would be nicknamed “o Casto,” the chaste. In the end, the king found no better legacy than the creation of a council to select a monarch from a list of several expectant candidates. Apart from internal claimants, others outside Portugal readied their own arguments, no matter how unlikely: even in France, some promoted scarcely tenable genealogical claims for the queen mother, Catherine de Medici, whose serious quest was shrugged off in Spain and Portugal. Others could not be taken lightly, and no aspirant caused more concern than Philip II, king of Spain, already the most powerful monarch in Europe. Those who formed part of a politically engaged public in Portugal recalled the tense relationship between their kingdom and neighboring Castile, considered the hard-fought independence of their proud nation, and pondered the possibility of Iberian unity under a Habsburg monarch.

Negotiations took place in daylight and in shadows. Outside Lisbon’s walls, Cristóbal de Moura, Spanish ambassador to Portugal, walked through a late-summer garden with Lope Centil, a local letrado. There, amid forced courtesies and implied promises, Centil agreed to write a foolproof defense of Philip II’s rights. The prospect excited Moura so much that he could barely sleep that night. Despite high hopes, however, the years between 1578 and 1583 showed that dynasticism alone would solve nothing. The specter of Spanish rule and the ambiguity of the moment unleashed currents of discord within Portugal that resulted in a civil war among several competing forces, some of which fought under the banner of Philip II and others under that of the homegrown pretender to the throne: Antonio, prior of Crato. Diplomacy, propaganda, and violence would ultimately establish six decades of precarious Habsburg dominion over Portugal and its overseas territories, starting with Philip’s coronation in 1581 and, more assertively, the defeat of Dom Antonio in the Azores two years later.

Discontent lingered in Portugal, but victory allowed Philip’s regime to develop a triumphant narrative. When the king arrived in Lisbon, festivities emphasized soaring expectations. As he stepped off his ship along the Tagus, the king stood before a triumphal castle-shaped arch. The temporary structure displayed a complex decorative scheme featuring an image of Philip dressed in military garb, standing victorious over Atlas with the world at his side and Neptune, trident in hand, with his upturned ship. Beneath the king’s depiction, austere Roman capitals celebrate Philip for his defense of the Catholic Church, his efforts to spread the faith “by land and by sea,” and those quintessential effects of good governance: the conservation of peace and justice. Beneath Atlas, a book lay open with an inscription describing his “broken body” and the weakness that led him to place the weight of the world on the king’s shoulders. Another beneath Neptune describes his own submission: having governed the seas for so long, now Philip is to keep watch so that “from now on, corsairs will not travel through these seas without punishment, nor will they take hostages, nor steal.” Those who organized the day’s celebration wanted to link the king to the mythical power of the gods and to suggest his global dominion. The regime later synthesized these sentiments in more durable form: a medal struck in 1583 advertised that for

Philip II, Non Sufficit Orbis —“the world is not enough.”

Such bluster may have been aspirational, given competing views and mixed feelings in Portugal, but it nevertheless promoted a perception of Habsburg might. From the outside looking in, the king’s victory against Portuguese competitors seemed like a coup. Across Europe, many were gobsmacked by the implications of Iberian unity and the newly extended Habsburg reach across the world. With his newly won Portuguese imperial holdings in Asia, Philip reigned over an empire upon which the sun never set.

From inside the regime, the thrill of victory inspired some to exploit the moment. The marquis of Santa Cruz, fresh off a successful armada campaign in the Azores (1583), wrote to Philip saying that if God had decided to make him “such a great king . . . it is only just that this victory be followed by the necessary provisions so that next year the English enterprise might be carried out.” The insistence on fighting England was not new, but in Santa Cruz’s mind, now it was feasible and desirable as a first step to eradicate heresy and stabilize Habsburg influence across Europe and beyond.

Some believed that defeating England would stifle fundamental threats to Philip’s authority. Bernardino de Escalante, a sailor (and later clergyman) with close ties to the Spanish court, reveals a typical pro-war stance. In 1586, he wrote a memorial to the crown epitomizing what had become a truism among many, contending that war against England was necessary to solve several intertwined threats. English corsairs had threatened transatlantic commerce, and England had openly supported rebels against the king. Escalante argued that defensive measures would be costly and ineffectual; it would be better to strike the problem at its source. Only the conquest of England would do. He advised the king to take note of Julius Caesar, who had realized that his efforts to keep Gaul could only be achieved by conquering England. By no other means “could he render them obedient, as he in fact did.” Should the king want to take control of his Burgundian territories (Belgium and Holland), parts of which had been in open rebellion since the 1560s, the time had come to destroy their abettors in England.

Escalante emphasized feasibility. He explained that the English were ambivalent subjects and expounded on the auspicious geopolitical situation. He asked Philip to consider geography as well: islands were more vulnerable than other places to unexpected attacks. He recalled the importance of surprise along open coasts during the initial conquest of Portugal and the

Azores campaign. The thrill of this success over the Portuguese continued to inspire the conquest of England.

Escalante wrote with freedom unburdened by power, but Philip II did not have that luxury. From the time of Elizabeth’s coronation (1558), his interactions with the queen were treated with appropriate delicacy. Even when the king’s personal feelings for the queen soured, even as Elizabeth’s Protestantism proved unwavering, he (and some of his important advisers) had little interest in war. Philip could not commit to aggression, especially amid instability on the Continent. He had to deal with the Dutch Revolt and reports that French heresy influenced his rebellious subjects there. Moreover, sources informed him that French Calvinists were planning to enter Iberian territories.

French Catholics also posed a threat. Franco-Spanish rivalries of the first half of the sixteenth century remained beyond the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), which had tried to allay them. The king’s hesitance about England was of a piece with his antipathy for the fleur-de-

lis. Should Philip interfere against Elizabeth, he would help the Scottish queen, Mary Stuart, who while imprisoned in England promoted her pretensions to the English throne. Mary was supported by her uncle, the duke of Guise, head of an influential clan in France with pan-European interests. Philip could applaud Guise efforts to defend French Catholicism but could not endorse their imperial designs.

Further, due to the multifront effort necessary to make an English expedition feasible, financing posed problems. While money came in shiploads from across the Atlantic, it was quickly spent. The second half of Philip’s reign was plagued by cash shortages and several defaults.

Religious considerations and forms of political prudence made decision-making tense. At times, Philip’s decisions resulted from messianic impulses, as described by Geoffrey Parker; at others, more earthly calculations dominated. However, as M. J. Rodríguez-Salgado has suggested, secular considerations and piety were not antithetical. Many took for granted that the good Christian king should first protect his own subjects.

When the English Jesuit Robert Persons left France for Portugal, he understood geopolitical realities but tried to overcome them. Persons emigrated from England in the 1570s, when English Catholic exiles had started to set roots in Belgium, France, and Italy. He quickly rose in the ranks after becoming a Jesuit and helped lead the first full-fledged Catholic mission back to England in 1580, along with the latterly sainted Edmund Campion. Campion was executed for his efforts, but Persons managed to escape to France where—despite deep emotional turmoil—he worked fervently toward fulfilling England’s salvation. To this end, he became embroiled in plots led by the Guise along with Scottish clergymen to lead a campaign against Protestants in Scotland and then to overthrow the Elizabethan regime in favor of Mary Stuart and her son, James. Persons tried to ensure the support of both the papacy and Philip—easier said than done.

In 1582, Persons approached Philip in Lisbon. He came prepared with a series of arguments in favor of immediate action. The proposed course was necessary for “the liberation of the Catholics who are distressed and persecuted for their faith in England and elsewhere, and . . . the restoration of God’s church in those regions, and the tranquility in other neighboring countries which have been troubled now for so many years by the malice of these heretics.” This appeal to Christian duty and this pitch for peace in Christendom came with a positive feasibility assessment. The moment was ripe given Catholic discontent in England and Scotland: Catholics were tired of oppression and fed up with perceived misgovernance. They were ready to fight against the “tyranny of heresy.”

Persons had to wait; Philip had fallen ill. Plans for a face-to-face meeting would be postponed, although communications with the regime began in earnest between Persons and Philip’s principal secretary, Juan de Idiáquez. Through this intermediary, Persons would learn of the king’s sympathy for English Catholics. However, cautious optimism soon faded. Philip could not offer full assistance until he resolved turmoil in Portugal—an armada was about to set sail against Dom Antonio in the Azores. Moreover, he needed more assurances that the papacy would contribute its fair share of money. Persons would not be the first nor the last Englishman to receive little more than encouragement from Philip. On his return to France, he became seriously ill in Spain but would live to fight on for English Catholicism. He would be back.

Monarchia

In England, many had greeted Philip’s success with dread. After the Portuguese conquest, Elizabeth’s counselors thought they saw the writing on the wall. William Cecil, Elizabeth’s chief minister, did not know “what limits any man of judgment can set unto his greatness” and warned of Philip’s “insatiable malice, which is most terrible to be thought of, but most miserable to suffer.” Philip seemed to be creeping toward the British Isles. He battled against French Protestants, and his regime explored ever more violent expedients against Dutch rebels. Should Philip succeed on both fronts, England would be next. The king’s efforts to establish universal monarchy posed an existential threat to church and state.

Elizabeth’s counselors seethed, but the queen was circumspect. In the 1560s, she had few qualms about supporting profiteering ventures in the New World, where Spain claimed exclusive trading rights. Adding to growing tensions, she stood by while an important shipment of gold to fund Philip’s war against Dutch rebels was held hostage in Dover in 1569. However, more direct engagements were avoided, largely because the regime feared Habsburg power and because the queen was unwilling to jump into perilous war. As her reign progressed—and in retrospect—many in and around court would become critical of her hedging. The explorer Sir Walter Raleigh would quip that the queen “did all by halves,” and the earl of Essex, her sometime favorite, would say that English governance was hampered by “delay and inconstancy, which proceeded chiefly from the sex of the queen.”

Calculations about foreign engagements were always embedded within domestic troubles. Because the Wars of the Roses left deep wounds, because Elizabeth was a woman, and because she was the last Tudor, she faced inordinate pressure to find the right husband. This created tensions between the queen, who considered the issue her prerogative, and subjects who advised, exhorted, and even tried to direct her. Without an heir, succession became a topic of overwhelming concern and a driving force of political culture throughout Elizabeth’s reign. Until 1587, many hopes and fears were pinned upon Mary Stuart. Elizabeth’s counselors convinced Elizabeth to allow Mary’s execution, but even then, the succession crisis did not flag, as the childless queen refused to consider her successor or allow others to discuss the matter despite the emergent possibility of Spanish dominion by dynastic arrangement or conquest.

Succession debates became part of a cosmic contest between Protestantism and Catholicism. Mary Stuart sought help from Catholic forces on the Continent, and as her confinement continued, she became more cavalier in those foreign entanglements. The regime linked her to murderous plots against Elizabeth and uncovered efforts to bring England under the dominion of the Guise and, even more troubling, Philip. The long period of Marian subterfuge solidified a feeling within the regime that the threat of foreign conquest was part of a massive Catholic conspiracy promoted by English exiles, “unnatural subjects” who had betrayed Elizabeth and welcomed the dominion of Rome and Madrid. Within this context, the idea of England as defender of pan-European Protestantism gained currency.

As Catholicism and foreignness became more intertwined, the place of English Catholics changed within England. From Elizabeth’s perspective, the challenges posed by religious dissidents to the regime were multifaceted and included a range of treasonous Catholics and no less treasonous Puritans. Many of her advisors would try to persuade her against what they saw as a false equivalence, and their case proved harder to ignore as time went on. A rebellion by Catholics in the north (1569) and the pope’s decision to excommunicate and thus encourage Catholics to reject the queen (1570) were early turning points. A major threshold was breached in the late 1570s and early 1580s, when important English Catholics formed part of a rebellion against the queen in Ireland while others led the first comprehensive mission from Rome to England. This was, according to the Elizabethan regime, a two-pronged rebellion. By the early 1580s, many became convinced that English exiles along with the pope and the king of Spain would one day awaken a fifth column within the queen’s realms.

The regime sometimes overstated the threat, but they did not invent it. The relationship between English Catholics and the Elizabethan government was varied and capacious enough to include several kinds of loyalties and disloyalties, but the exile community abroad posed specific challenges. From the early days of Elizabeth’s reign, some wealthy Catholics attached to the court and a trickle of academics and priests felt forced to leave England as a result of resurgent Protestantism. They went to Catholic lands and became embedded in their new homes, often with the support of England’s enemies. Some, especially in their early years of exile, did not become politically active, but others did in hopes of using foreign pressure to remove the queen and reestablish Catholicism.

Persons’s appeals to Philip II epitomize the threat to Elizabethan stability. He went to see the king in Lisbon with England’s salvation in mind but was ready to engage in hard-nosed politics. Not only did he hope Philip would be part of a pan-European invasion of England and Scotland, but he was willing, as John Bossy has argued, to consider the gravest of tactics: Elizabeth’s murder. If the Elizabethan regime would characterize such scheming as treason, Persons saw it differently. His entrée into dirty politics was a requisite of unfortunate times. Catholics were killed and exiled while the insidious powers of Protestantism destroyed the true Church and, consequently, the commonwealth. Rejection of heresy, even by the most extreme measures, was justified in defense of the true faith. If Catholicism needed to be reinstituted by Spanish forces, so be it. English Catholic exiles found themselves between the proverbial rock and hard place. Not welcome at home, they had to hustle on the Continent for subsistence and for a greater cause: to save their homeland.

Excerpt ends here.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.