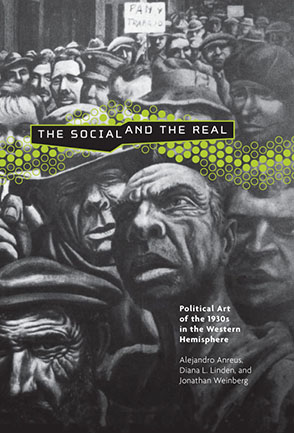

The Social and the Real

Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere

Edited by Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg

The Social and the Real

Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere

Edited by Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg

“The Social and the Real looks at 1930s art in a hemispheric context and fills a very real need. . . . Taken individually, the essays . . . represent important contributions to scholarship. . . Considered together, they enlarge in striking and unanticipated ways our understanding of the art of this period.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

In sharp contrast to earlier studies, The Social and the Real contends that the radical, “realistic” art of the Americas during the 1930s was shaped as much by hemispheric exchange as by emulation of the European avant-garde. Alan Trachtenberg, Mary K. Coffey, and the book’s other essayists consider Canadian art alongside art from the United States, the Caribbean, and as far south as Argentina. Some of the artists they discuss, like Philip Evergood or Dorthea Lange, are well known; others—the Argentinean Antonio Berni or the Canadian Parakeva Clark—deserve wider recognition. Situating such artists within the context of Pan-American exchange transforms the structure of the art-historical field. It also produces major new insights. The rise of Social Realism, for instance, is traced back not to the United States in the 1930s, but instead to the Mexico of the early 1920s.

The Social and the Real makes an assessment of Social Realism that is comprehensive as well as groundbreaking. The opening essays deal with “reality and authenticity” in representation of “the nation.” Subsequent essays consider portrayals of manhood, labor, lynching, and people pushed to the margins of society because of religious or ethnic identity. The volume concludes with a pair of essays—one on artists’ links with Communism, the other on the portrayal of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s physical infirmity— that carry the discussion of Social Realism into the postwar period.

The Social and the Real is the first anthology to deal with the painting, sculpture, graphic arts, and photography of the 1930s in a hemispheric context. We take as axiomatic Cuban poet, journalist, and political theorist José Martí’s (1853–95) definition of “America” as a hemispheric, multiracial, and multiethnic entity in which the United States is one nation among many. Although many of the individual essays have a relatively narrow focus, as an aggregate they begin the process of forging a Pan-American perspective on the art of the period, encouraging the reader to compare and contrast the experiences of artists across national boundaries and reconsider familiar narratives. Thinking about art and politics in a hemispheric context expands the very chronology of social realism. Whereas scholars in the United States locate the origins of the movement with the economic crash of 1929 and conclude it with the advent of World War II, the story really begins in Mexico in the early 1920s and continues during the 1940s and 1950s throughout the hemisphere.

“The Social and the Real looks at 1930s art in a hemispheric context and fills a very real need. . . . Taken individually, the essays . . . represent important contributions to scholarship. . . Considered together, they enlarge in striking and unanticipated ways our understanding of the art of this period.”

“The 14 eclectic essays focus on a single topic—an artist, movement, or subject. All reveal fascinating facts and analyses that incrementally add to a better understanding of this period.”

“This collections approach proves quite refreshing, lending more legitimacy to the study of a still-neglected phase of art history. [Other] essays in this welcome volume add the issues of race and sexuality to the discussion of social realism in the United States and Canada. Most readers will come away from this book with a clearer view of political art as a hemispheric phenomenon.”

Alejandro Anreus is Associate Professor of Art History and Latin American Studies at William Paterson University. Diana L. Linden is a visiting Assistant Professor, Pitzer College, Claremont, CA. Jonathan Weinberg is an artist and Fellow, Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New School University.

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I. Representing the Nation: Reality and Authenticity

1.Signifying the Real: Documentary Photography in the 1930s

Alan Trachtenberg

2. Social and Political Commentary in Cuban Modernist Painting of the 1930s

Juan A. Martínez

3. The “Mexican Problem”: Nation and “Native” in Mexican Muralism and Cultural Discourse

Mary K. Coffey

4. Canadian Political Art in the 1930s: “A Form of Distancing”

Marylin McKay

5. Adapting to Argentinean Reality: The New Realism of Antonio Berni

Alejandro Anreus

Part II. Men, Manhood, and the Male Body

6. Want Muscle: Male Desire and the Image of the Worker in American Art of the 1930s

Jonathan Weinberg

7. Making History: Malvin Gray Johnson’s and Earle W. Richardson’s Studies for Negro Achievement

Jacqueline Francis

8. Lynching and Anti-Lynching: Art and Politics in the 1930s

Marlene Park

Part III. Labor and Labor Conflict

9. Art and Politics in the Popular Front: The Union Work and Social Realism of Philip Evergood

Patricia Hills

10. Workers and Painters: Social Realism and Race in Diego Rivera’s Detroit Murals

Anthony W. Lee

Part IV. Voices on the Margins

11. “Come Out from Behind the Pre-Cambrian Shield”: The Politics of Memory and Identity in the Art of Paraskeva Clark

Natalie Luckyj

12. Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene

Diana L. Linden

Part V. Extending the Discourse

13. Between Zhdanovism and 57th Street: Artists and the CPUSA, 1945–1956

Andrew Hemingway

14. The President’s Two Bodies: Stagings and Restagings of the New Deal Body Politic

Sally Stein

Index

Introduction

Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg

The Social and the Real is the first anthology to deal with the painting, sculpture, graphic arts, and photography of the 1930s in a hemispheric context. We take as axiomatic Cuban poet, journalist, and political theorist José Martí’s (1853–95) definition of “America” as a hemispheric, multiracial, and multiethnic entity in which the United States is one nation among many. Although many of the individual essays have a relatively narrow focus, as an aggregate they begin the process of forging a Pan-American perspective on the art of the period, encouraging the reader to compare and contrast the experiences of artists across national boundaries and reconsider familiar narratives. Thinking about art and politics in a hemispheric context expands the very chronology of social realism. Whereas scholars in the United States locate the origins of the movement with the economic crash of 1929 and conclude it with the advent of World War II, the story really begins in Mexico in the early 1920s and continues during the 1940s and 1950s throughout the hemisphere.

There were numerous threads of contact between artists throughout the Americas. These included artistic inspiration through the reproduction and dissemination of images, artists either traveling to, working in, or exhibiting in countries other than their own, or inviting foreign artists to work with them, as with the numerous artists who assisted or worked with the Mexican muralists in either Mexico or the United States. Artists’ organizations were important sites of contact, among them the American Artists’ Congress, which convened in 1936 in New York and whose twelve delegates included José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The Mexican Artists’ Union inspired both the Artists Union and the Harlem Artists’ Guild in the United States, the Union de Escritores y Artistas in Cuba, and the Artists’ Union of Canada, whose members were involved with either the Communist Party or the social-democratic Cooperative Commonwealth Federation.

It was at the 1936 American Artists’ Congress that U.S. muralist Gilbert Wilson related how two summers before he had seen Orozco’s extraordinary paintings for the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. “From that moment on I knew it was what I wanted Art to be—a real, vital, meaningful expression, full of purpose and intention, having influence and relation to people’s daily lives—a part of life. Here was the first modern art I had ever seen. At least, it was the first creative work done in my own time that seemed to have any need, any excuse for being. I decided that murals, today, can contain one of two things, either the cruelty of emptiness or the cruelty of truth.” In contrast to the rhetoric of nationalism and isolationism that was gaining increasing currency in the culture of the United States by the mid-thirties, Wilson acknowledged that the contemporary mural movement had begun in Mexico and that an art of social responsibility was in essence a Pan-American phenomenon. As artist and critic Charmion Von Wiegand wrote, “It is even possible that they [the Mexican muralists] may give us a tradition from which the American painters will draw. For, as their country like ours belongs to the New World, their work seems to be a part of our actual native expression.” As the essays in this anthology aptly demonstrate, artists throughout the hemisphere shared Wilson’s and Von Wiegand’s call for an art that was both responsive to the day-to-day struggles of the working classes and had a wide appeal. Such popular understanding did not mean sugarcoating reality; instead Wilson wanted murals that would convey the “cruelty of truth.”

It may still surprise some readers that Wilson used the word “modern” to refer to the work of the Mexican muralists who had rejected the abstraction of the European avant-garde. The supposed antimodernist quality of so much of the visual art between the wars has resulted in its neglect by an approach to art history that still favors formal invention over content, abstraction over realism. And yet all the artists discussed in The Social and the Real, no matter what their nationality or style, shared a belief that they were making art that was distinctly modern precisely because it responded directly to the political and social issues of the times. But, as Paul Wood writes, “the mere depiction of recognizable bodies doing recognizable things was not what made an art ‘realist.’” In its most cohesive and authentic visual expressions, social realism synthesized the formalist experimentation of the avant-garde with a critical interpretation of reality. Such artists as the Mexican muralists were opposed to academic naturalism because it seemed to maintain conservative values. But they were equally opposed to avant-garde forms of expression because of their supposed elitism and bourgeois individualism. Painters such as Stuart Davis in the United States, Paraskeva Clark in Canada, and Antonio Berni in Argentina wanted to reconcile modernist painting with leftist ideology. The social dimension of reality and the reality of social conditions are crystallized in the most powerful art of this period.

Our focus on intrahemispheric exchange and artistic production is a break from the dominant modernist paradigm that sees art of the Americas as solely indebted and subservient to European art. This is not to deny that many artists from Canada, the United States, the Caribbean, and Latin America traveled to Paris and Berlin in the 1910s and 1920s for training, camaraderie, and inspiration. But their travels to these European capitals were often taken after exposure to the Mexican muralists or after having lived and worked in Russia and Eastern Europe. Artists in Latin America and the Caribbean drew upon native radical political, indigenous artistic traditions, and upon their own national and popular heroes. In sum, the art of the Western Hemisphere represents a dialogue between politics and art both within the Americas and with European modernism and politics.

However, in emphasizing Pan-Americanism, and in particular the extraordinary influence of the Mexican mural movement, we cannot ignore the economic, military, and cultural imperialism of the United States. If artists outside the United States welcomed a certain amount of cross-cultural exchange, they also wanted to protect their native art production from the culture industry of their “good neighbor.” The social and political manifestation of nationalism in Latin America and the Caribbean functioned on two levels: It sought to recover the historical past that reinforced the authenticity of indigenous artistic and social traditions (José Carlos Mariátegui’s Marxism, for example, was rooted in Incan communal social structures); and it promoted a left-wing anti-imperialist nationalism, as evident in the politics of Peru’s Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA), Nicaragua’s César Augusto Sandino, Puerto Rico’s Pedro Albizu Campos, and Cuba’s Antonio Guiteras. These nationalisms throughout the Spanish-speaking Americas, as seen in the visual work of Mexican, Argentinean, and Cuban artists, absorbed rather than rejected the formal experimentation of the European avant-garde, which was then transformed into a national visuality that was neither chauvinistic nor nativist. The stylistic example of Diego Rivera, with its linear composition, bright colors, and didactic narrative, had repercussions in the Caribbean and the Andean countries. Rivera’s heterodox politics (he evolved from Lovestone to Trotsky to Mao in a little more than a decade) was not as influential as that of Siqueiros, which was grounded in the Communist Party network throughout the Americas. Of the three great muralists (los tres grandes), Siqueiros traveled the most throughout the Americas, lecturing, publishing articles, and conducting workshops. While his “dialectic-subversive painting” alienated potential followers with its communist dogmatism, his sculptural sense of form found adherents in Berni (Argentina) and Mario Carreño (Cuba). In the end, the socially engaged realism found in Latin American art between the two world wars was pluralistic in both style and content.

<1> Historiography

Our title, The Social and the Real, is derived from the term “social realism,” which has become a standard catchall to describe the numerous public murals, graphics, and easel paintings produced between the wars that had some kind of leftist content. Social realist art tends to criticize the body politic or propose an ideal community. A term accepted both popularly and by scholars, it is vague and remains largely unexamined. The beginning of its use in the art-historical literature of the United States is hard to pinpoint. During the 1930s artists in Canada, Latin America, and the United States never referred to themselves as social realists or to their art as social realism, a fact noted by many of the essayists in this volume; nor did the critics use the term. In Canada such leftist artists as Marian Scott, Fritz Brandler, and Louis Muhlstock, working in Montreal, referred to their imagery as “proletarian art.” Charles Hill, in his Canadian Painting in the Thirties, discusses the “social function” of art with a decidedly working-class orientation. It appears that the term social realism first appeared in the Canadian art-historical literature in Barry Lord’s History of Painting in Canada: Towards a People’s Art, published in 1974. David Shapiro’s widely read and referenced Social Realism: Art as Weapon, published in 1973, has resulted in the scholarly acceptance of the term to refer to leftist art in the United States, but it has since been adopted in studies of both Canadian and Latin American art of the period.

Despite the variability of the terms by which artists referred to themselves, through their political involvement, through their imagery, manifestoes, political networks, and public demonstrations, many artists engaged in debates over the artist’s role in society, the role of the government in funding the arts, and how to create works that were both aesthetically and politically progressive. If Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco never used the term social realism, they always believed that art should have a direct political and social function, and they went so far as to embrace the word propaganda—a term always used negatively by modernist and antimodernist critics alike. As early as 1923 the manifesto of the Union of Mexican Workers, Technicians, Painters, and Sculptors declared: “The creators of beauty must turn their work into clear ideological propaganda for the people, and make art, which at present is mere individualist masturbation, something of beauty, education, and purpose for everyone.”

David Shapiro describes social realism in terms of socialist politics, and writes that “Social Realism attempted to use art to protest and dramatize injustice to the working class—the result, as these artists saw it, of capitalist exploitation.” Art historian Patricia Hills, a contributor to this volume, defines social realism as not so much a style but “an attitude toward the role of art in life” that emerged during the mid-1930s. Cecile Whiting suggests a more inclusive definition that includes art with “social, though not sectarian messages.” These writers emphasize the message of the art rather than its formal vocabulary, and its potential to create class consciousness that can lead to social change. Most art historians insist on a clear distinction between social realism and Socialist Realism, the officially sanctioned style of the USSR. First conceptualized in 1932 by Karl Radek and Nikolay Bukharin, the doctrine of Socialist Realism was first presented to an international audience in 1934, when Andrei Zhdanov, secretary of the Communist Party and Stalin’s chief cultural commissar, addressed the first Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow. Socialist Realism was official, academic, and controlled by the Communist International in Moscow, and according to Zhdanov was the only art appropriate to “the building of Communism.” The nomenclature social realism, by contrast, has some of the flavor of the ideals of the Popular Front. Just as the Popular Front was an attempt to put allegiance to communism aside so as to unite leftist artists and intellectuals in the struggle against fascism, social realism as a construct brings together a wide range of left-leaning artists regardless of their relationship to the Communist Party. To paraphrase cultural historian Michael Denning, social realists do not necessarily adhere to any one political dogma, but they “labor on the left.” For every Hugo Gellert, a member of the Communist Party who illustrated the writings of Karl Marx, there were many more artists like Paul Cadmus, who participated in things like the NAACP-sponsored exhibition “An Art Commentary on Lynching,” (13 February–2 March 1935), was a member of the Artists Union, and signed the 1936 call for the American Artists’ Congress. (As Jonathan Weinberg points out, Cadmus said his politics were “pinkish” rather than red, alluding archly to both his homosexuality and his political leanings.)

More troubling than the variety of terms used to describe the leftist art of the period—“social realism,” social viewpoint,” “social content,” and “proletarian art”—is the vagueness of their meanings. In 1933 Meyer Schapiro, writing under the alias “John Kwait,” complained in the New Masses about the lack of focus of the John Reed Club of New York City’s exhibition “The Social Viewpoint in Art”:

<ext>

What is The Social Viewpoint in Art? It is as vague and empty as “the social viewpoint” in politics. It includes any picture with a worker, a factory or a city-street, no matter how remote from the needs of a class-conscious worker. It justifies the showing of [Thomas Hart] Benton’s painting of negroes shooting crap as a picture of negro life, or a landscape with a contented farmer, or a decorative painting labelled “French Factory.” The mere presence of such “social” elements in a picture does not indicate any social viewpoint, since these elements are often treated abstractly and picturesquely without reference to a social meaning of the objects.

<end ext>

Schapiro dreamed of a different exhibition, one that would include “examples of cooperative work by artists,—series of prints, with a connected content, for cheap circulation; cartoons for newspapers and magazines; posters, banners; signs; illustrations of slogans; historical pictures of the revolutionary tradition of America. Such pictures have a clear value in the fight for freedom.” He called on the John Reed Club “to offer specific tasks, especially cooperative tasks, to the revolutionary artist.” Jacob Burck defended the exhibition from Schapiro’s attack, insisting that the goal was “to rally all artists whose sympathies are swinging leftward. It served its function well historically by making a thorough resume of this new development among the artists. Until the economic crisis, art (painting, sculpture) was entirely a snobbish, individualistic expression based on the ‘gold standard’ of bourgeois society. The ‘social viewpoint’ in politics, is of course absurd, but the social viewpoint in art is a decided change leftward from its former one of ‘bananas and prisms.’”

We find ourselves in sympathy with both positions. On the one hand it seems absurd to limit the discussion to works by those relatively few artists in the Western Hemisphere who were self-consciously communist. At the same time, like Schapiro, we are worried by the vagueness of the terms used to designate and understand the art of the left. Recognizing that the term social realism was not contemporary, we wished to pull the term apart and examine its two separate components—the first indebted more to the realm of politics and sociology, and the second to nineteenth-century literary and artistic traditions. And so we challenged the authors of this anthology to rethink some aspect of the crucial words “social” and “real.” How did government and community function in the career of individual artists? What role did a conception of “the masses” or “the proletariat” play in the artist’s understanding of his or her task? Do works of art from the period simply mirror powerful economic and social forces, or did they accomplish political work, causing people to think and act differently, creating a lasting impact on the social structure? To what degree was representation itself understood to be a matter of ideological struggle, so that the work of art conveyed not only the truth of everyday life but also the mechanisms of truth telling?

By inviting essayists to reconsider the meaning of both the social and the real, we asked that they broaden the social issues of the era beyond the dominant one of class and labor. In the end, such reconsideration brings into question the “realness” of the artists’ social vision, which often projected utopian social ideals—active healthy workers at a time of mass unemployment, racially harmonious workforces despite heightened racial conflict, and the absence of images of women as wage earners and laborers. The contributors to this anthology explore how the representation of race, gender, and sexuality operates within the visual culture of the period and how these things interacted with the class struggle.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.