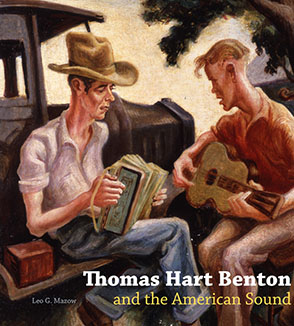

Thomas Hart Benton and the American Sound

Leo G. Mazow

“Leo Mazow’s much-anticipated Thomas Hart Benton and the American Sound contains many delightful surprises. For one, it opens up Benton to new lines of inquiry: much has been written about this modern American painter, and authors have long noted his interest in music—especially American folk songs—but now, at last, we have a book that considers Benton’s trenchant absorption in American sound in the context of diverse theories and the rich pageantry of his era. Moreover, the book is superbly researched and well written. And in rendering Benton and his interests as fresh and novel, Mazow performs an enormous favor for anyone interested in modern American culture. Here’s yet another guise for a controversial and outspoken artist. A superb book that’s sure to leave a lasting mark.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Leo Mazow’s much-anticipated Thomas Hart Benton and the American Sound contains many delightful surprises. For one, it opens up Benton to new lines of inquiry: much has been written about this modern American painter, and authors have long noted his interest in music—especially American folk songs—but now, at last, we have a book that considers Benton’s trenchant absorption in American sound in the context of diverse theories and the rich pageantry of his era. Moreover, the book is superbly researched and well written. And in rendering Benton and his interests as fresh and novel, Mazow performs an enormous favor for anyone interested in modern American culture. Here’s yet another guise for a controversial and outspoken artist. A superb book that’s sure to leave a lasting mark.”

“An interesting and compelling project exploring the centrality of ‘sound’ in the work and career of American artist Thomas Hart Benton.”

“While the main focus of Thomas Hart Benton and the American Sound is to show the many levels of influence that the idea of not just music, but also sound, had on his visual work, what really is at the heart of Mazow's book is the notion that as an American artist working in the twentieth century what drove Benton's works more than anything else was the trials, tribulations, lives, passions, movements and dramas of real American people.”

“In this beautifully written and well-illustrated study, Mazow . . . traces the impact of American vernacular music on the murals and easel paintings of the celebrated regional artist Thomas Hart Benton. . . . Mazow goes beyond the mere citation of the presence of musical instruments and performance in Benton's paintings to include a provocative thesis that the artist was interested in the almost ephemeral pursuit of trying to represent sound—the noise and cacophony of trains, cars, jackhammers, speakeasies—and to discuss how this abstract idea informed Benton's concept of the American scene.”

“Leo Mazow’s book offers a new model for examining artworks that combines formal, archival and social analysis with fascinating results.”

“Mazow’s Thomas Hart Benton and the American Sound reverberates with potent ideas about the relationship between the history of visual art and sound. By contextualizing Benton’s paintings within a sonic environment—a world of radio, recordings, the whistles of trains and the scream of machinery—Mazow illuminates our understanding of the artist’s formal designs and rhythms and expands the manner in which we perceive his vernacular subjects. Delightfully written in language that sings and shouts along with its themes, Mazow’s book offers an entirely new way of relating Benton’s work to the sounds of his time.”

“One of the finest contributions of Mazow’s project is that it seamlessly links Benton’s Regionalist agenda with his aural endeavors, highlighting the artist’s interest in not only folk songs, but also . . . numerous modes of civic discourse. The reader can see that Benton’s life was filled with town hall meetings, lectures, sermons, and, one can imagine, many “shooting the breeze” conversations with the citizens of the regions that he visited for months at a time. With so much imagery and so many overlapping themes and issues regarding sound in Benton’s oeuvre, imagining Benton’s own oral history is no small task. In effect, Mazow dissects the artist’s crowded, hyperbolic narratives to point out significant sonic moments—their visual language, the biography of the subjects, and the circumstances of the scene—while building an overall cohesive framework that organizes these sound bites of history for the reader.”

Leo G. Mazow is Associate Professor of American Art History at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Painting the Song

2 Painting the Sound

3 Anthology

4 Regionalist Radio: Benton on Art for Your Sake

Epilogue: Sound, Touch, and Beyond

Appendixes

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Alternately praised as “an American original” and lampooned as an arbiter of kitsch, the regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton has been the subject of myriad monographs and journal articles, remaining almost as controversial today as he was in his own time (fig. 1). Time-honored understandings of this seemingly ubiquitous artist are, however, deeply enriched through investigation into the profound ways in which sound figures in his enterprises. Prolonged attention to the sonic realm yields rich insights into long-established master narratives, corroborating some but challenging and complicating at least as many. So much has already been written on Benton, and yet the sonic inquiry casts critical and clarifying light on many intersections and contradictions within the artist’s work, suggesting novel and revelatory engagements with much twentieth-century American art and cultural history.

Benton’s work is strikingly visual—big murals, impressive figures, and colorful, busy, active compositions. But when examined carefully, his painted scenes reveal a deep engagement with other senses, particularly that of sound. Aurality—voice, musical instruments, the sounds of machines and recording devices—is referenced throughout his work. A self-taught and frequently performing musician who invented a harmonica tablature notation system used in music tutorials to the present day, Benton was also a collector, cataloguer, transcriber, and distributor of popular music. Historians and critics have acknowledged these activities as primarily musical phenomena (that is, when the literature attends at all to the musical aspect). This book, however, shows that musical imagery was part of a larger belief in the capacity of sound to register and convey meaning. In Benton’s pictorial universe, it is through sound—and its visualization—that stories are told, opinions are voiced, experiences are preserved, and history is recorded. All that is consequential, or so the artist would have us believe, has both voiced and heard components.

Walk through a gallery showcasing Benton’s art or leaf through the pages of a monograph or exhibition catalogue. Look and listen—the former act quickly leads to the latter. Platform-mounted politicians shout their dogma. Preachers scream with upraised hands as adherents intone with bodily acknowledgment (fig. 2). Chugging locomotives and propeller-driven aircraft compete for attention (fig. 65). Phonographs and behemoth generators induce all within earshot to dance and gyrate (figs. 34, 72). Typewriters, telegraphs, and stock tickers clack with the steady din of communication and commerce, their aural presence penetrated by the cacophony of neighing horses, whirling turbines, and metal-ripping pneumatic drills. Meanwhile, larger-than-life guns sound explosive discharges, sending renegade protesters and cheating husbands running for cover. And then there’s the artist’s visual inventory of musical instruments and performers. Drums, guitars, harmonicas, fiddles, pianos, saxophones, trumpets, and tubas are matched by their skilled performers and open-mouthed vocalists (fig. 3). In many passages, musical notes and ray lines denoting piercing volume literally set the stage and compose Benton’s tableaux.

A remarkably high percentage of Benton’s mature work depicts musical performance, instruments, singing, and clapping. Even more pieces take as their subject the production of sound in nonmusical contexts; these include meteorological phenomena, sound-receiving and -transmitting technology, discharging guns, wild animals, boisterously revivalist religious services, various feats of manual and mechanized labor, chugging trains and steamboats, objects falling and bodies bumping, filibustering politicians, and miscellaneous historical incidents. Compositionally, Benton enlisted a wide range of devices—such as bellowing lines, exaggerated perspective, and echoing forms—to imbue his art with audio analogues. This litany of sonic components demonstrates that Benton considered sound itself meaningful and, one might say, meaning forming.

A reasonable response to the above paragraph might be that in Benton’s art we see—not hear—the plucked banjos, vrooming aircraft, screaming preachers, campaigning politicos, firing guns, and blaring radios and other electronic equipment. But still we have formal and iconographical clue after clue inviting us to listen—to folk songs, to orators, to oral histories, and so on—and often to participate, to respond. Benton depicted Americans making their way in the world by means of sonic practices. I am obviously discussing the imagery of sound, but I am also interested in the measures taken by the artist to make his art, and often his point of view, heard. He did this through the lecture circuit and broadcast technology, for starters. The latter performances were a sort of adjunct to the formal tropes, symbolism, puns, and painted lyrics that register sound in his work. Benton understood sound as a complex but reliable barometer of experience, and in his art he frequently referred to arcane, difficult-to-visualize sonic effects. What, for example, does a metaphor such as “the voice of the people” look like? Moreover, why would an artist feel compelled to paint, or an audience want or need to see, “the voice of the people”? This admittedly ubiquitous phrase was fundamental to the pluralism and participatory politics championed by Benton’s populist and democratic forebears (his father and great uncle, his namesake, were congressmen), and his visualization of political spheres typically entailed an engagement with sounding one’s opinion. Benton’s art contains so much aural subject matter and so many sonic formal devices because he recognized sound as an all-revealing (and occasionally concealing) phenomenon, the presence of which permeates countless aspects of American and world history. Benton recognized that sound is everywhere in our personal and professional lives, in our worldviews. It occupies the core of our thinking and feeling.

In the last two decades, scholars of American cultural history have increasingly turned their attention to sound, among other senses, as primary source material. In this regard, the work of historians Mark Smith, Leigh Schmidt, Emily Thompson, Richard Cullen Rath, Peter Charles Hoffer, and others is exemplary because it simultaneously introduces sonic approaches and uses those methodologies to understand myriad narratives. While music and synaesthesia are occasional topics in the literature on historic American art, with few notable exceptions—including but not limited to the work of Asma Naeem, Caroline Jones, and Alexander Nemerov—sound itself has by and large escaped prolonged scholarly engagement among Americanists. My debts to these art and cultural historians are fairly apparent in the pages that follow; I would like to think that I join these scholars in the double task of introducing and applying a series of sonic approaches.

A Biographical Note

Thomas Hart Benton remains one of the most written- and talked-about artists in twentieth-century American art history. Thanks in at least some degree to the artist’s agents and his own self-promotion, something like a biographical formula recurs in Benton’s writing and secondary sources past and present. The fundamentals of this narrative can be summarized in a few paragraphs. Born in Neosho, Missouri, Benton rejected the political calling of his father and great uncle and pursued an artistic education at the Art Institute of Chicago, with additional stays in New York and Paris constituting an informal continuation of his studies. Stimulated by European modernism and encounters with Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Alfred Stieglitz, the artist produced experimental canvases in the 1910s and 1920s, often grafting impressionist, cubist, futurist, and Russian constructivist idioms upon both traditional subjects (still lifes and landscapes in particular) and, increasingly, identifiably American subject matter. At the tail end of World War I, while serving as an architectural draftsman in the Navy in Norfolk, Virginia, Benton experienced an awakening to the expressive possibilities of things—“building[s], the new airplanes, the blimps, the dredges, the ships”—as opposed to modernism’s “colored cubes,” as visual barometers of American experience. Sitting at the bedside of his dying father, “Colonel” Mycenaeas E. Benton, in 1924, the artist listened to the stories told by friends, neighbors, and family members who dropped in. Their memories of the colonel worked further to suffuse Benton with an interest in an experiential history of the United States.

Benton’s first artistic endeavor in this direction was a multi-panel visual unfolding of American history, collectively entitled The American Historical Epic. Produced from 1919 through 1925, the project never received the backing of a sponsor, although fourteen of the panels would be publicly exhibited. Benton merged mannerist elongation and coloring with cubist spatial principles in pictorially narrating key events from the settling and early development of the New World and colonies. He never completed the massive project, although in the 1930s he produced four commissioned public murals that effectively continued his visual history of the nation: America Today, for the New School for Social Research (1930); The Arts of Life in America, for the library of the Whitney Museum in New York (1932); A Social History of the State of Indiana, for the Indiana state pavilion at the 1933 Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago; and A Social History of the State of Missouri, for the state capitol in Jefferson City (1936).

A prolific printmaker and book illustrator, Benton would also create several large easel paintings that won him both fame and, on occasion, infamy. Among the better known of these are The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of Lone Green Valley (1934; fig. 9) and Persephone (1938; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City). In comparison to his output from the interwar years through the end of World War II, Benton’s paintings, prints, and murals of the 1950s through the 1970s—during which time his stylized, representational aesthetic receded in popular esteem—have not received much scholarly discussion. However, Benton was as prolific as ever during the Cold War years, and these monuments enrich discussions of the artist’s sonic sensibilities.

Additional, important biographical details have been amply provided by such scholars as Henry Adams and Matthew Baigell, and much of this literature is listed in the bibliography. As will quickly become apparent, I rely heavily on these groundbreaking studies. In this book, however, I have opted to not retread the artist’s biography further, in part because it has already been treated so thoughtfully by previous historians. Moreover, my argument hinges on what I see as some underemphasized yet critical aspects of the “Benton story”—notably his engagements with music and sound in general—and I fear that these crucial points might easily get lost amid Benton’s hyperbolic claims and sumptuous surfaces. Benton’s sonic sensibilities, I am suggesting, merit as much scrutiny as the hoopla, confrontation, controversy, and shifting politics that mark most narrations of the artist and his work.

Musical Beginnings: Waxahachie, Chicago, and Paris

In the pages that follow, I argue that Benton explored and sought to preserve the culturally significant sounds of much more than songs, performers, and performances; work, oral history, religion, violence, and weather are as much his sonic subjects as music itself is. Still, it is worth recounting in some detail Benton’s early introductions to opera, big band, gospel, and classical and folk music because they demonstrate the parallel development of his aural and visual tastes. These musical encounters facilitated his thinking critically about sound as an index of expression—national, personal, and otherwise—at a very young age. Finally, Benton’s early avocational enthusiasm suggests that music and sound may have been as important to his personal and professional development as the party politics and accompanying political culture into which he was also thrust. For Benton and countless others, both art and participatory politics involved critiquing and celebrating cultural history and reclaiming a vision of some supposedly vanishing American origins. And both involved sound as a critical means for registering, emitting, and receiving information.

During Benton’s youth, the sounds of piano playing saturated his home in Washington D.C., where his father served as a U.S. representative. The Bentons had a “concert grand piano, not just a grand piano,” Benton’s sister Mildred would remember. When Benton was an adolescent, his mother immersed the family in classical music and other entertainments in her frenzied desire to elevate them to what she viewed as the standards of cultivated society within elite political circles. Other sounds—with a cadence and key all their own—also permeated the young man’s experiences, as the clatter of politicians and a host of raconteurs accompanied political life and the campaign trips on which he often joined his father. Throughout this study, it is very important to bear in mind Benton’s political lineage, as the son of a U.S. congressman and the great nephew and namesake of a famed democratic senator, the Missourian Thomas Hart Benton (1782–1858).

Whatever music, sounds, and noise Benton may have heard in that household, however, he would later confess that “in my youth I never knew anything about the personal satisfactions that come from making sequential sounds.” But if musical taste and aptitude could be inherited, Benton certainly would have picked them up from his mother’s side of the family—with whom he visited often—based largely in and around Waxahachie, Texas. The entire brood was “musical and every member of the family either played an instrument or sang,” recalled the artist in his unpublished and unfinished autobiography “The Intimate Story.” “Their music, hymns of the southern hills mostly,” Benton continued, “and some balladry from Scottish and early English sources and a few of the popular songs of the eighties and nineties [were] well known and acclaimed in Waxahachie.” The mention of the Anglo-European ballads is helpful in accounting for the preponderance of early folk music of the British Isles within the canon of songs that Benton collected, performed, and transcribed. Religion reigned supreme in the vocal traditions in which his mother was steeped. He remembered that his mother and her sisters “were famous for their hymn singing in three or four parts and even people who ridiculed their religious fanaticism came to their little churches to hear them.” From an early age, then, Benton knew and surely witnessed firsthand the emotional states and ideological claims to which music might aspire. Even so, although his mother was an avid piano player, Benton would not take up the harmonica until much later in life.

While a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1907 and 1908, Benton had something of a musical awakening. Music and reading were his great avocations during these years. After dinner and a full day of work and study, on most evenings he would read Plutarch, Tennyson, and the Bible, effectively augmenting his education. Yet he still managed to spend an inordinate amount of time attending the concerts of bands and street musicians, events that impressed upon him the power of sounds harmoniously arranged to move audiences, to affect one’s psychological makeup, to produce unexpected, sensitivity-heightening experiences. One day, for example, Benton attended an “orchestra concert” by Albert Ulrich’s orchestra at Fullerton Memorial Hall, at which he heard the music of Strauss, Bach, and others performed. He was very excited when the Metropolitan Opera came to town in spring 1908, anxiously writing to his mother about the prospect of seeing both Tristan and Isolde and Faust, and urging her to ask his father what he thought of these pieces.

Benton increasingly charted his musical literacy during these years, particularly in letters to his mother. After attending the “Italian Opera” in September 1907, he proudly told her, “I am getting more and more acquainted with music all the time.” Following an Easter service in 1907, at which he was among “7,000 in attendance,” he was deeply moved, writing that “the music was grander than ever.” While in Chicago, he also went to amusement parks to hear orchestras led by Bohumir Kryl, Francesco Ferullo, and other famous bandleaders. He delighted at being able to see these performances for such little cost: “What during the winter you had to pay 1 to 5 dollars to hear,” he noted, “you can get now for ten cents.”

Benton’s favorable impressions of these bands suggest his growing awareness of the potential of sound to reach, and have a significant impact on, large segments of the population. This was a subject with which he would be much preoccupied later in life as he lectured, performed, and broadcast his art and persona. In a letter to his mother, he recalled a Ferullo performance he had attended at the San Souci Amusement Park at Sixtieth Street and Grove Avenue in Chicago. As much as he loved the music, Benton was most overwhelmed by its entrancing effect on the enormous crowd (which he perhaps overestimated at 75,000), a Coney Island–esque spectacle of which he was part. Benton wrote that he had “heard Ferullo lead his band, or more properly I saw him. I have never heard finer band music in my life. As a general thing I didn’t think an American crowd could be much affected by music but the one last night was.” In this description, hearing competes with seeing, but perhaps most telling is the artist’s recognition that sound could hold sway over a community. He would retain this interest in the activities of sound makers and sound receivers throughout his life.

By the time Benton began his study in Paris later in 1908 (he would remain there through 1911), musical and sonic metaphors had already entered his artistic lexicon. Before going overseas, he was obviously fueled by aestheticism, praising “James McNeill Whistler[’s] . . . tone, colors harmoniously arranged. . . . Whether you can distinguish one object from another or not, whether the thing painted looks like a man, woman, or dog, mountain, house or trees, you have harmony and the grandest artistic aim, it is the truly artistic aim.” Seeing Whistler’s much-ballyhooed masterpieces was, in fact, one of Benton’s key reasons for going to Paris. There his sonic sense was again piqued by musical offerings. When he was not reading Carlisle, Wordsworth, and Victor Hugo (an activity about which he bragged in his letters to his parents, written in French), he was often attending concerts and recitals. He saw bands and dancers perform in commemoration of La Bastille, among other productions. At this time, Benton may well have conceived and/or produced now lost works relating to music and performance, which in turn, as discussed in chapter 2, surely informed his engagement with synchromism and ultimately soured him on the makeshift movement. Finally, during his French sojourn, Benton showed signs of a nascent musical and sonic vocabulary, with which he would describe visual phenomena for the rest of his life. The landscape inspired the artist’s thinking in this expository mode. For example, he would remember of the area near Tulle, which he visited in 1910, the “sounds of falling water, the flute[-]like music of a stream jumping over rocky edges and making drumbeat rhythms in the pools below.”

First articulated in these musical episodes and encounters, the sonic sensibility would provide a great resource for the artist from the 1910s through his last works in the 1970s. Songs, sounds, their reification, and their transmission are the subjects of a large portion of Benton’s art, writing, and professional practice.

Sounding Thomas Hart Benton

Chapter 1 of this study, “Painting the Song,” takes stock of Benton’s most important paintings that depict musical performance and/or passages from folk songs. In this endeavor, he shared with several musicians and musicologists a desire to counter highbrow prejudices in music and culture at large. Balancing the serious study of music with the folk forms that such study reveals, Benton appears intellectually allied with his friend and occasional bandmate, the pioneering musicologist Charles Seeger. Both men envisioned folk music as a primary source in the study of American culture and sought to bridge the gap between vernacular expressions and their public appreciation as legitimate art. This chapter examines in some detail the subgenres in folk music that most attracted Benton’s attention, demonstrating their common emphasis on the transmission and receiving of sound itself. With subjects taken from such classic folk songs as “John Henry,” “I Got a Gal on Sourwood Mountain,” and “Frankie and Johnny,” Benton found in music and lyrics both a worthwhile subject and a mediating force. For the artist, musical compositions were about quickly disappearing folkways, but as artistic subject matter they also provided a methodology with which to rehash the values he attributed to their composers, performers, and audiences. We might borrow Marshall McLuhan’s words and conclude that for Benton music was both medium and message. In each of these song-based compositions, by depicting musicians performing and by concentrating on key sonic moments in the lyrics, the artist transformed the songs into metasongs, whose ultimate subject concerned the articulation or expression of that subject or message. I show that Benton relied on a sort of musical metonymy, with climax moments completing the narrative, and that he made use of metalyrics, passages about the sounding of words (e.g., conversations, protests) and the production of noises (e.g., train whistles) themselves.

In chapter 1, I also show that Benton consistently relied on foreground figures playing the music and reciting the lyrics that are enacted, rehearsed, or otherwise performed by the middle- and background characters. In his paintings Minstrel Show (1934; fig. 11) and The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of Lone Green Valley (1934; fig. 9), as well as the lithographs Coming ’Round the Mountain (1931; fig. 7) and I Got a Gal on Sourwood Mountain (1938; fig. 8), this compositional trope alternately brings the music to life and presents sonic barriers that beholders and selected audiences are warned not to cross. This chapter also suggests that in appropriating lyrics from songs climaxing in death and destruction—what we might call “fatality plays”—Benton gravitated toward characters who literally spoke with their guns, which invariably articulated what their voices never could. Thomas Hart Benton and the protagonists in Jesse James (1936; figs. 13, 14) and Frankie and Johnny (1936; figs. 15, 16) turned to paintbrushes and guns, respectively, in part because of their fear that they would otherwise be disregarded.

Among the volumes in Benton’s library was George A. Wedge’s Rhythm in Music (1927). This textbook argues that the “physical development” of rhythm “is inherent in all normal human beings and upon this basis artistic creation is developed.” Although primarily interested in “the aural sense,” Wedge stressed the wide applicability of a theory of “reiterated sound,” arguing for its foundational presence across media and genres. Benton may or may not have been directly influenced by Wedge, but, as I suggest in chapter 2, his compositions consistently enlist the “muscular techniques” described by Wedge and others in order to suggest pulse, beat, and reverberation. Entitled “Painting the Sound,” this chapter demonstrates the omnipresence of musical metaphor and sonic wit in Benton’s art, surveying his pictorial strategies for the visualization of sound. Related to Wedge’s “physical” rhythm are concomitant statements of harmony, dissonance, chord, and key throughout Benton’s paintings, drawings, and prints. These formal dynamics begin with—but elaborate on—the artist’s trademark interlocking planes, reechoing forms, and ray lines. Subject matter joined with Benton’s innovative techniques to suggest sound; punctuating his oeuvre are microphones, antennas, radios, dancers, open mouths a-singing, and figures literally moved by noise or sedated by harmony.

Benton similarly enlisted formal elements in his sound-evoking mission. He frequently turned, for example, to elongated rays, collapsed perspective systems, and narrative-containing and -expanding cones or funnels. As we will see, these strategies came in handy particularly in the artist’s sonic engagements with religious culture (in the articulation of the Word and the Spirit) and political life (in the democratic ideal of “the voice of the people”). Critical models for this foray include sociologist Les Back’s notion of “listening with our eyes” and political scientists Nancy S. Love’s and John Rawls’s suggestion that human vocality lies at the heart of individual autonomy. I conclude with case studies of Benton’s portraits of his friends Carl Ruggles (1934) and Edgard Varèse (1932), whose theories of dissonance and omnidirectional sound projection animate the pictures in which they appear.

Throughout his life and with steadfast passion, Benton turned to myriad art forms and genres to make the case that music joined—and in many instances rivaled—painting and drawing as indices of folk experience. However, in a now famous passage in his first autobiography, An Artist in America (1937), Benton spoke fatalistically about the future of those experiences registered by sound, as if deeply afraid that once our indigenous musics are sidestepped for impure commercial derivatives, records of lives will be lost. “The old music cannot last much longer,” he remarked. “I count it a great privilege to have heard it in the sad twang of mountain voices before it died.” In chapter 3, “Anthology,” I outline the strategies used by the artist to make the music last, so to speak—from collecting and transcribing music to giving pictorial form to climactic moments in American music and cultural history. In this activity, he joined an elite roster of performers, musicologists, and historians who enlisted music to document a vanishing America. Among these individuals was Benton’s friend Charles Seeger, who, as an assistant to John Lomax, spent much of 1939 cataloging and transcribing songs for the Archive of American Folk Song. Benton was also friendly with John and Alan Lomax, who on a few occasions consulted with the artist regarding his travels and recordings. Benton, in turn, assembled his own archive by way of musical tablature notations, lyric collections, and song illustrations. Passing these lessons on to his friends and students and often articulating musical ideas in public forums, such as in periodicals and at dinner parties, Benton recognized that sound was an ideal means for registering and conveying information—perhaps not quite on the level of painting, but certainly in tandem with it.

Demonstrating that Benton treated his murals as so many painted anthologies, chapter 3 also compares Benton’s anthological mode with that of Alfred Stieglitz, with whom he had a long, father-and-son-like friendship and whose encomium America and Alfred Stieglitz: A Collective Portrait (1934) he reviewed in Common Sense, concluding that the book anthologized none other than the photographer himself. Finally, those human subjects of Benton’s paintings and oral histories, whom we increasingly encounter in his art, offer key insights into the larger theme, because so often (as in the cases of Wilbur Leverett and Chick Allen) they are themselves deeply invested in the anthological enterprise, dedicated to sonic-archival endeavors. Benton, that is, anthologized the anthologizers.

Benton did more than simply depict radios, phonographs, and other electronic images. The alternately rhythmic and static compositional tropes with which he limned musical and so much other imagery also characterize mass media and, in particular, the experience of listening to radio. In fact, Benton was a frequent radio guest in the 1930s and 1940s, again merging painted narratives with their sonic extensions. Chapter 4, “Regionalist Radio,” examines a dramatization of the artist’s life on the NBC program Art for Your Sake in early 1940. This script underscores with uncommon clarity the ideological foundations of the modernist radio style as Benton understood it in paint: national interconnectedness, easy movement from zone to zone, and an ever-expanding litany of subjects and addressees. With folk music and sound effects punctuating the broadcast, the radio program points to Benton’s carefully calculated efforts to enlist the aural as a critical component in the visual preservation of vernacular cultures. This chapter shows, however, that this collaboration between artist and broadcaster was only one in a lifetime of attempts to appropriate sound in a crusade to impose a fixed identity on an American public. A key argument in this book is that for Benton and the regionalism he championed, constructing a national identity in the 1930s and 1940s and through the Cold War years was only one part of the movement’s agenda. Getting through to that nation—physically, emotionally, and often aurally—was just as important. Radio was integral to this effort, complementing allied activities such as Benton’s mail-order distribution of lithographs through the firm Associated American Artists.

What Makes a Conversation Sacred?

The case studies in these chapters explore books, oral history, periodicals, radio, and newsreels—in addition to paintings—as sonic phenomena and intellectual catalysts. Of course, we do not hear the paintings or other visual products in any conventional sense of “hearing.” Yet it is the sonic unconventional to which Benton so often aspires. Were we to place ourselves within the tableau, miraculously travel through time and into the picture, and somehow coexist with the subjects of a sonically attuned painting, we still might be unable to hear the conversation, the noise, and the like. This is the case with Benton’s depictions of individuals whispering; and, as discussed below, this phenomenon is yet more problematic and suggestive in his portrayals of deaf persons. Several of the works seem to be orally and aurally present—evoking voiced and heard communication—for the subjects depicted, but this sound would surely be either inaudible or simply nonexistent were we to encounter the scene played out before us.

This dynamic transpires in the artist’s lithograph Gateside Conversation (1946), based on an earlier painting of a subject he first sketched in southern Louisiana (fig. 4). Crossing a makeshift plank bridge over a ditch or small stream, a mule-drawn carriage has stopped, its physical presence punctuated by the clouds roughly echoing its top contours and stressed further by the vehicle’s dark mass silhouetted against the much lighter background (apparently the result of leaving the lithographic stone untouched, especially at right). This is one of a few Benton images with “conversation” in its title, providing an opportunity to comment on the nature of “sacred” voice and “special” sound as I am using these terms.

In the case of Benton’s conversational subject matter (which also appears in works whose titles do not contain the word “conversation”), we are left wondering, what could the conversation be about? In Gateside Conversation, the two figures at left and the standing figure at right conform to Benton’s oft-used conventions for depictions of Anglo and African American individuals, respectively. The elevated status of the white men in the enclosed carriage, who are placed higher than the bucket-lugging laborer, suggests a power relationship.

Any number of the artist’s racially loaded paintings, prints, murals, and drawings might support such a reading. On the other hand, such a literal, content-driven interpretation may be missing the point. Gateside Conversation is, in effect, about conversing and the visual forms that sonic discourse can take. And on this front, Benton provides several clues and cues. The laborer places his hand atop the wheel, his own form echoing the arc of the wheel, his protruding hat at left roughly fitting into the jigsaw puzzle–like void between the hat rim, mouth, and torso of the driver. The standing figure’s hat compositionally acts as the base of an implied arc formed by the headwear of the three individuals, as if he is the recipient of some sort of orders or other communication. Conversely, we might read the discursive line as running in the opposite direction, with the carriage-bound men listening to the laborer’s report or other statement. The formal dynamics of this lithograph point to a recurring motif in Benton’s work: conversing or relaying information as subject matter, either in tandem with or as a subtext to more obvious themes.

One goal of this book is to demonstrate the importance of sound imagery within the artist’s output and the artistic, political, economic, religious, geographical, and other contexts and situations in which he worked. Of course, I strive to ascertain what the pictures, and their conversations, are about. Yet a larger theme emerges, even when we know selected facts about the pictured “story.” For Benton and the histories he is narrating, sound—the right to sound, who gets to sound in the first place, who hears what, who ignores what—more often than not is the story, the point of the picture. Sound is everywhere, relating meanings but also forming meanings, and so its presence is key to any painted or otherwise limned narrative. Although formally and iconographically ubiquitous, elements of sound play a special role. Benton’s achievement was the distillation of sound in visual and other, supposedly extra-sonic contexts, and, as discussed in the epilogue to this book, it presents methodological possibilities far beyond regionalism and mid-twentieth-century America.

Benton’s painting Conversation (1928) further demonstrates the pictorial workings of sound in both its surface and more profound meanings (fig. 5). The three horses share a space intersected by their respective gazes. The painting’s title as well as the subjects’ compositional placement and gestures all suggest a discourse escaping a bystander’s ability to hear or comprehend. The animals inhabit a seemingly muted locale described by a critic in the pages of Parnassus in 1939 as “the crystalline vacuum of the desert.” The horses’ “conversation” is what I have called meaning forming, but it is also theoretical and subjectively realized; it demands an imaginary leap, and a prolonged dipping into possible narratives, to fully “get it,” to enter what is otherwise a narrative “vacuum.”

Our inability to enter the horses’ sonic zone does not diminish the expressive richness or even the sacredness of the conversation. Benton’s always astute critic Lewis Mumford found in the deceptively simple, modestly scaled Conversation a different, perhaps transcendent, form of communication, a sort of volume that is more meaningful than the racket found in his horror vacui murals. Contending that the artist maintains in “his smaller paintings a sense of the peace and beauty and lonely wistfulness of man facing the earth,” Mumford suggested that “there is more of a living, breathing humanity in Benton’s landscape of three horses on a wide prairie . . . than there is in his most crowded external representation of a city crowd.” I mean to suggest that the seemingly straightforward actions of sounding and listening can be—for Benton and countless others—subtle and nuanced. Historian Emily Thompson has written that “the physical aspects of a soundscape consist not only of the sounds themselves, the waves of acoustical energy permeating the atmosphere in which people live, but also the material objects that create, and sometimes destroy, those sounds.” In both Conversation and Gateside Conversation, and in numerous other pieces by Benton, we witness the creating and redirecting of a sonic community, even if we do not physically hear the two-dimensional works in which they are visually depicted.

In a portion of an unpublished manuscript dating from 1950 or the late 1940s, Benton elaborated on his innovative formulation of sound in general, and on music’s appeal to deep-seated emotional states unreachable through other senses in particular. Entitled “The Nature of Form,” the essay describes at some length the challenges faced in describing musical forms. Benton is especially concerned with the concept of sonic or “sonal emotivity.” “Music rests,” he writes,

on primary emotional responses; it arouses, that is, responses which are prior to and deeper than those occasioned by the defined meanings of language. The cry is before the word. The meaning of music, as a pure succession of sounds, is really more akin to the meanings which some wild animal of the forest might connect with a succession of forest sounds than with the definite meanings of language or those even of visual experience. To hear an approaching, but unseen lion would certainly cause more terror (i.e., more poignant emotion) than if his position and path were defined in language or vision.

Later in the essay, he uses the example of a cat in both its expository forms (the sentence “there comes a yellow cat”) and sounded forms (the sound of “meow”). Animal metaphors serve him well because they demonstrate “indefinite associations, often remote and unstable,” carried by sounds, their makers, and their receivers. Further, Benton writes that musical notation and form (he uses the examples of rondo and sonata, and of the pattern “A + B + A”) do not mean anything to most listeners; by themselves, this shoptalk does not describe or lay hold to our aural sense. Although it was almost certainly never published, “The Nature of Form” represents a theoretical breakthrough for Benton, a summation of the tenets underlying his faith in the complex character of sounds and sounding. In the context of his essay, one need not be able to hear the actual conversation in the painting Conversation for it to have sonic resonance. The conversation, we might reason, is in fact all the more “sacred” because of the inaudible, “primary” origins of utterances.

At stake for Benton in the sonic realm are meanings and understandings that might otherwise go unspoken, even unnoticed. They may be theoretical and ethereal, but they provide the basis, an alphabet-like foundation, for envisioning lived experiences and for sharing and preserving the information contained therein. Benton’s regionalist agenda repeatedly emphasizes that which only exists in language, lore, conversation, and silences. It also bestows primacy on the ability to suggest and engage visually those bangs, booms, bustles, collisions, and other sounds—cacophonous and euphonious—through which information and feeling are communicated.

Talking and Being Heard

Nothing else defines me so intimately as my voice, precisely because there is no other feature of my self whose nature it is thus to move from me to the world, and to move me into the world.

—Steven Connor, Dumbstruck

So often in Benton’s work, visualized feelings and pieces of information narrate the artist’s own subjective encounter with objective data, such as laws, institutions, economics, literature, and the history of art. To a large extent, the sonic themes and vocally suggestive formal conventions in Benton’s art continue the emphases on the oral cultures and aural immersions that Benton first knew as a little boy. As soon as he could talk, he was taken by his father on campaigning trips throughout the Ozarks, where the younger Benton witnessed democracy playing itself out through networks of eloquent oratory, persistent declamation, and unrehearsed conversation. By the time Benton published An Artist in America in 1937, the world of his otherwise sullen father had become enlivened upon recall of his verbal skills. “Full of rollicking stories,” he wrote, “my Dad . . . was a great eater, drinker, and talker.” Upon arriving in a town, the touring political candidate was “supposed to yell at the top of his voice for a couple of hours. I’ve seen my father do this time and again.” Young Benton’s home life in Washington and Neosho was not much different: “Our dinner table was always surrounded with arguing, expository men who drank heavily, ate heavily, and talked over long fat cigars.” Speech got politicians elected, it enabled otherwise voiceless constituents to be heard, and it provided the channel through which opinions were articulated and differences resolved. Voicing was—and, in large part, still is—a dominant expressive mode. As we will see in chapter 1, Benton was particularly attracted to songs—as artistic and musical source material—that had identifiably rich traditions of having been passed down through public and private lore. Indeed, part of the sonic drive for Benton was an emphasis on oral cultures, on speaking and sounding as ways to preserve history and perpetuate respect for it.

By the time Benton reached his artistic maturity, his actions and demeanor somewhat resembled those of his father and his political cronies. Like a peripatetic, politicking candidate, for much of the period from the mid-1930s onward, Benton traveled widely and frequently to cities and towns to speak at chambers of commerce, college campuses, art schools, and other organizations, putting—or attempting to put—salient aspects of his evolving regionalist ethos into words. Thus, people heard from Thomas Hart Benton, as opposed to only encountering his art or reading about it. One of the artist’s first widely promoted presentations was a public debate with Frank Lloyd Wright in Providence in 1932, which was co-sponsored by the Rhode Island School of Design and Brown University, organized and broadcast under the aegis of the Community Arts Project, and funded by the Carnegie Corporation. Typifying these high-profile speaking opportunities, in June 1933 the artist addressed the Hoosier Salon Patrons Association and the Daughters of Independence at the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago, where his mural A Social History of the State of Indiana was on view. The following year, at the request of Audrey McMahon of Columbia University and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Benton embarked on an extensive national speaking tour, seeking “to encourage interest in American art in general.” Developed by McMahon in the hopes of gathering broad public and political support for the WPA, the traveling lecture series took the artist “from Pittsburgh over the Mississippi Valley and westward to Lubbock, Texas.” Surely a smart choice on McMahon’s part, Benton, by 1937, could be characterized as being “as skillful in debate as he is with his brush.” The following decades were dominated by still heavier lecture schedules at venues across the nation. Alternately denouncing European modernism, prescribing roles for “the” American artist, and commenting on painting’s past, present, and future, Benton both spoke and painted his personally crafted versions of regionalism.

Mid-January 1935 found Benton traveling by plane to accommodate a tight schedule that included successive presentations in Chicago, St. Louis, Milwaukee, San Antonio, Dallas, and Springfield, Missouri. An observer in the latter city wrote, “A man being paid $1 a minute to talk ought to have something right interesting to say!” In June of that year, he lectured in Wyoming, Colorado, and again in southwest Missouri. So rampant and enterprising were Benton’s seemingly never-ending lecture and promotion tours in the 1930s that they became something of a joke to his brother Nat (and perhaps to others as well). Nat, an attorney in southwest Missouri, concocted a story in which the artist was touring the nation lecturing on the merits and qualities of coffee royale (coffee to which brandy or whisky, sugar, and heavy cream have been added). He joked that his brother had “lined up a big coffee manufacturer and then got a contract with a large firm of brandy importers, and they’re paying him a lot of money to go around the country lecturing on coffee royale.” Even by contemporary standards—including the media-blitz campaigns of politics and movie debuts alike—Benton did a great deal of speaking, and of broadcasting his Benton-ness. But he also brought art and art commentary to the regions, meeting the regionalist criteria of cultural accessibility and availability.

Also in 1935, in a letter to his on-again, off-again friend Mumford, Benton admitted his propensity to edit, re-edit, respond to, and perhaps over-think his public expressions. On the face of it, Benton’s note is an acknowledgment of Mumford’s recent review of an exhibition of his work. But the artist also reveals an awareness of his inner drive to think, write, and talk things through, to fulfill his own criteria for being understood: “I thought well of [Mumford’s review]—so well that as soon as I saw it I sat down and started writing you about it. Before I knew it I had written twelve pages like this one. Well you know when I write twelve pages I must write twelve more to qualify and clarify and by that time I’m off in a long discussion with myself which goes beyond the province of a letter.” As his extensive lectures, panel discussions, and radio and television appearances demonstrate, going “beyond the province” often meant speaking, sometimes obstreperously so. In the same year, Mumford summarized Benton’s promotion of regionalism in such terms, balking at the artist’s manner of “strutting around and shouting defiantly in the archaic fashion of the Riptail Roarer from Pike County, Missouri.” Always attentive to his critics, even (perhaps especially) when he claimed not to be, Benton stated in his earlier letter to Mumford, “You have made it plain to me that I must work up a verbal expression of the set of values which are behind my work.”

Perusing Benton’s oral presentation topics alongside his visual production, one gets the sense that, for him, paintings and other visual arts media were meant to spark conversation, just as discourse of one sort or another had sparked the subject matter of so many paintings. With such dialogue approaching a definition of pluralism—a participatory, populist conception of culture in which all could speak and all would be heard (if only via paint)—perhaps Benton truly was, as art historian Elizabeth Broun once put it, “a politician in paint.” Perhaps this is the legacy of his congressman father and senator great uncle.

On several occasions, however, Benton turned to press conferences, interviews, and public forums to settle the controversial aftermath of this or that painting or mural. For example, to address the widespread negative comments provoked by the brutally frank—and inaccurate, according to many—depictions in his mural A Social History of the State of Missouri (1936), Benton held a question-and-answer session at the Kansas City Art Institute, followed by similar events at the Community Church and the Junior League in Kansas City. His public appearances straddled a fine line between being educational, proactive, and confrontational. Benton merged intelligence with an in-poor-taste, good-ole-boy excuse for humor at an April 1941 press conference, in which he made homophobic comments about art museum professionals; by May of that year, this incident would cost him his job. In June, he toned down his comments in the pages of Common Sense, taking aim at the newly formed National Gallery of Art and what he viewed as the plethora and cultural irrelevance of American museums.

But the artist’s relatively sensitive treatment of museums and art education in Common Sense did not have anything of the splash of his earlier, widely reported homophobic rant. As Benton was surely learning, his words, his speaking, carried at least as much weight and popular appeal as his art and writing. This quality brought him myriad lucrative speaking engagements and won him the acclaim of critics and students from different walks of life. But the events of April 1941 also showed Benton’s mouth to be his own worst enemy. As he summed it up in the Common Sense article, “For talking, I lost my job.” A more accurate assessment might be that he lost his job for offensive, demeaning comments and insubordinate behavior. Benton meant for his utterances and speeches to complement, to explain, the folk quality of his art; however, as with many politicians, his speaking occasionally revealed his own personal shortcomings more than it attested to his professional acumen.

Regardless of whether he was actively courting controversy, press and fanfare typically greeted Benton’s engagements, emphasizing an oral/aural counterpart to his visual expressions. The brochure accompanying a lecture he gave at UCLA in 1941 stressed that the producer of this “explosive” art indeed “does have a story to tell.” As we will see, Benton frequently told his “story”—compulsively recounting his biography—and expressed his views on network and local radio programs in the late 1930s and 1940s (see appendix 1). In late 1940, he was also the subject of a newsreel. In 1951, long after a bitter feud between Benton and Stuart Davis had lost much of its sting, the radio program America’s Town Meeting of the Air featured both men responding to the question “Does modern art make sense?” This activity would only escalate as Benton got older, thanks in large part to television fueling the cult of personality. As early as 1944, the NBC radio-television simulcast Passing Parade featured an episode entitled “Grandpa Called It Art,” starring Benton, Charles Burchfield, and Reginald Marsh. In 1957, he was interviewed by Dave Garroway on Wide Wide World; in 1959, he discussed his art with Edmund Morrow on Person to Person; and in 1962, John Ciardi interviewed him on the program Accent. By the 1950s, Benton’s speaking and touring seemingly “went international.” In 1952, a Kansas City travel agency enlisted him as the tour guide for a special excursion to South America. The ad copy emphasized, in addition to the continent’s “old world charm” and “famous . . . food and hospitality,” the chance to “sketch . . . paint . . . [and] photograph” and to attend “special receptions and dinners with local artists” and other notables.

Beginning in the early 1940s, Benton offered testimonials in one print advertisement after another. In 1942, several of his paintings featuring tobacco subject matter appeared in Lucky Strike cigarette ads in Time magazine, with the copy emphasizing the “famous artist” whose page-dominating picture served as an implicit endorsement. His paintings would offer silent testimonial in print ads for Maxwell House coffee as well. But of particular interest are those ads in which the artist appears in profile adjacent to the marketing hyperbole, as if Benton is speaking the text below in a sort of comic-book balloon. As discussed in chapter 2, thanks to the Kansas City advertising firm Allmayer, Fox, and Reshkin, Benton’s visage appeared in mid-1950s ads for the Loomis Advertising Company, an advertisement broker for telephone directories. As in the 1952 travel agency ad, the sober face, with pipe in mouth, announces the worthiness of the service being offered. A 1946 advertisement for Parker pens in the Saturday Evening Post further exemplifies this trend. Above Benton’s all-business facial expression suspended from the margins of the ad (effectively endorsing the product), italicized text reads, “In the hand of Thomas Hart Benton.” The suggestion is that the arm and hand we see holding the pen belong to Benton, the angle of whose pipe parallels that of the pen below. The “world-famous artist,” according to the text, endorses “‘51’ . . . the world’s most wanted pen.” By the time he appeared—along with Douglas Fairbanks, Benny Goodman, and a bevy of authors, diplomats, and other celebrities—in advertisements for Lockheed Luxury Liners in 1957, Benton had joined the ranks of those whose word you could take as a sign of quality and assurance. If Benton said so, the good or service could be trusted and was worth its mettle.

To a great degree, people were hearing—and later seeing—Benton speak about his art and American art in general. He clearly viewed the vocal transmission of information as an adjunct to the work begun in his art. It may well not have mattered how the point was made so long as it was broadcast or emitted in some form. Benton’s lecture schedule and radio broadcasts suggest that he prized sonic formats as well as—and at times on a par with—visual formats. Being heard, that is, complemented being seen; personal utterances went hand in hand with art exhibitions and review articles. Amid the controversy of Benton’s murals in the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City, a journalist in 1937 might have intended to be literal, not metaphorical, when he wrote, “For months past the art world has been hearing much about mural paintings depicting the history of the State of Missouri.” At worst, this earned Benton a reputation as a “loudmouth.” Several commentators viewed his writings in oral/aural terms; a reviewer for the Washington Daily News, for example, dubbed his 1937 autobiography, An Artist in America, “outspoken.” This was a harsh version of a more representative summation of the book that gives his frankness oral and aural proportions: “Mr. Benton talks right out loud and doesn’t mince matters.” The headline “Outspoken Benton Still Speaks Out” ran in a Louisville newspaper in 1954, accompanied by a series of photographs of the cigar-chomping artist, with his own words transcribed beneath the close-ups. In the mid-1960s, shortly after Benton suffered a heart attack, a story in a Kansas City magazine assured its readers that he had resumed his vocation, adding, “We’ll be hearing from him too, or he wouldn’t be Thomas Hart Benton.” One contemporary art historian has commented that Benton was “an aggressive individual who demanded to be heard,” and this is part of the “colorful, larger-than-life image” that “comes to mind” when we think of him.

But what does it mean to “hear” Benton? What was at stake in “demanding to be heard”? When newspapers and magazines wrote that the artist was “at it again,” they often intimated a sonic side to the nuisance. Being a “loudmouth” was the outward expression of his own personal and admittedly idiosyncratic interpretation of his forebears’ populist legacy. Benton knew well and, as a child, experienced the Populist and Democratic Parties’ strategies for empowerment as well as their calls for both pluralism and the equitable distribution of wealth. Foregoing the family political vocation, he indeed approaches Broun’s conception of the artist as a “politician in paint.” Painting, though, joined speaking and being heard on that legislative stage. Shortly after being forced to leave his teaching post at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1941, Benton gave a speech entitled “Art and Democracy” to the city’s Young Democratic Club in which he proposed that “democracy is technically the art of government by majority voice.” Whether he was speaking literally is not certain, but he clearly equated equitable government with the unfettered voicing of one’s opinion. It is the task of this book to demonstrate that Benton frequently enlisted art to speak—to have the effect of words spoken, to persuade, to protest, to remember via oral history—in ways that his own voice could not, or could only realize in part.

Benton, then, was more than simply loquacious; he believed deeply that pictures, their subjects, their makers, and their audiences find a natural adjunct in the world of things spoken, sounded, and heard. And this adjunct was more than a variation on Horace’s famous dictum ut pictura poesis—“as in painting, so in poetry”—although he surely knew of this concept. Benton’s art and philosophy addressed not just the world of things verbal and written but also the world of things spoken, uttered, and otherwise made audible. This belief informed his catalogue of artistic subject matter and yet went deeper, figuring prominently in his idea of what constitutes a “good” painting. Perhaps thinking of the integration of parts into a whole, upon which so much of Alberti’s compositio and istoria hinges (in the architect’s treatise On Painting), Benton made a theoretical equation between the unification of a composition and the construction of a sentence. In his speech to the Young Democratic Club in 1941, he compared an artist composing a picture to a child “mouthing” a coherent sentence:

People do not know how to make forms, instinctively. They have to learn how to make them. Children do not make sentences when they first open their mouths. They have to learn to do so. A sentence is a linguistic form—a form made of words—a good sentence, a good linguistic form, is difficult to make. It takes a lot of years of learning to do it well. The technique of sentence-making is a tricky business. The more you know about it, the trickier it gets. This trickiness comes from the fact that sentence-making is for the purpose of carrying meanings—and meanings are elusive, especially when they get beyond the “Paw pass the butter” stage. To get the meanings which are in your head into a suitable linguistic form is a job. Unless you are going to keep your meanings strictly private (which may be a good idea in some cases) you have to get them related, and tied up together. That’s the only way you can get them to make sense to anybody else. The tying and relating of meanings to word-associations results in a verbal form. Unless you can make such a form, you can’t speak sense. When you can make such a form, you’re an artist. . . . You do like a child learning to make sentences.

It is not enough to paint a courthouse on a town square or the people under its jurisdiction; Benton goes a step further in Courthouse Oratory (ca. 1940–42), where the speaker leans forward and gestures with his hand as he orally proclaims this or that point (fig. 6). The orator in this picture is, above all else, “mak[ing] sentences,” and therefore “speak[ing] sense.” It is not enough to paint a preacher warning of hellfire and brimstone; he must raise his hands, open his mouth, and, in the case of Arts of the South, stand against the words “GET NEXT TO GOD” (see fig. 2). Like the preacher, Benton must connect the “forms” in order to be intelligible, to make a difference, to state an opinion, to have a say. What is at stake—formally and thematically—in so many of the pictures in this book is the dynamic of “being heard.” At an infamous 1934 lecture to the Art Students League and John Reed Club, after a heckler shouted, “I always knew you were a dirty anti-semite Benton,” the audience began chanting, “We want to be heard, We demand to be heard.” Benton replied, “Well you’re finally being heard.” He admitted, in an autobiography late in life, that he was just unable to get the last word, to orate to the very end; he knew that other voices were ganging up on his.

Vox Humana

In one of the last interviews he gave, the famed oral historian Studs Terkel lamented the diminishing presence of what he called the vox humana. Terkel recounts arriving, at the last minute, inside the closing automated doors of an airport shuttle—presumably the sort that carries passengers from one terminal to another—only to find himself and his fellow latecomers, a young couple, greeted by the announcement “Because of late entry, we’re delayed thirty seconds.” As Terkel describes it, the other passengers looked at the trio in disbelief, as if they had just witnessed a crime; of course, these earlier arrivals did not say a word, instead meting out their silent punishment. Trying to add levity to the situation, Terkel shouted, “George Orwell, your time has come and gone!” Still no word from the other passengers. “My God,” he exclaimed, “where’s the human voice?” One of those silent on the shuttle was a baby, whom Terkel asked, “Sir or madam, what is your opinion of the human species?” This drew laughter from the infant, and Terkel rejoiced, “Thank God—the sound of a human voice.”

Like Terkel, Benton ultimately sought to restitute the vox humana, to protect it against the suffocating pace and efficiency-minded doors of modern life. The comparison is admittedly imperfect; the punishment Benton received from his critics and naysayers was rarely of the silent sort. But both men were oral historians who found in the human voice the presence of life. The recorded, pictured, and otherwise mediated voice functioned for Benton and Terkel as a sign of immediacy and authenticity, much as it has, the curator Thomas Trummer observes, for several modern and contemporary artists. This book, in turn, explores the conditions under which Benton kept the vanishing past alive, present, and credible by way of sonic intimations. “When we hear someone, we are enabling them to speak to us,” notes Trummer. Yet Benton was selective, to say the least, about whom he chose to listen to. In his murals, paintings, prints, editorials, lectures, and broadcasts, was Benton really speaking to others, or to himself, or perhaps to his family inheritance? I do not think that we can take stock in cliché in this instance and conclude that he always or uniformly sought to speak to “all of the above”; the following chapters suggest a deeply subjective, at times personal, element to his visual engagements with public and political matters. These case studies suggest that Benton’s pictures cast and recast voices, echoes, and silences in an effort to reckon with the shortcomings of history and circumstance.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.