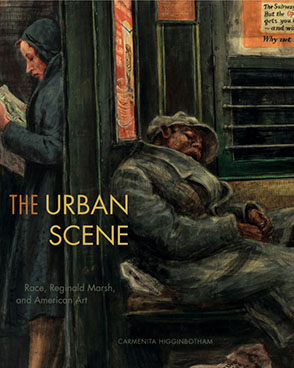

The Urban Scene

Race, Reginald Marsh, and American Art

Carmenita Higginbotham

“A scholarly project undertaken with clarity and precision, The Urban Scene is an important and innovative contribution to the literature on American culture and art during the interwar decades.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“A scholarly project undertaken with clarity and precision, The Urban Scene is an important and innovative contribution to the literature on American culture and art during the interwar decades.”

“The Urban Scene skillfully re-creates for readers the social and racial contexts in which Reginald Marsh’s paintings first circulated. The book deftly explores early twentieth-century artistic practice, urban development, consumerism, and racial identity to help readers better understand how white and black audiences made sense of the artist’s canvases of blacks.”

“Readers of this finely nuanced interpretation of Reginald Marsh’s African American imagery will gain a clear sense of the artist’s positive—and negative—contributions to American Scene painting’s portrayal of race during the Depression. With close attention to stylistic, critical, and social contexts, Carmenita Higginbotham cogently reveals Marsh’s pictorial balancing act. His integrated portrayals of New York’s subways, beaches, Harlem nightclubs, and Bowery dives intimated a more democratic opening of the urban scene. But they simultaneously offered visual containment to keep blacks in place. Such pictorial strategies, Higginbotham argues, provided a comfortable and negotiable imagery for Marsh’s white upper-middle-class audience.”

“Carmenita Higginbotham explores how Marsh’s late 1920s and 1930s paintings of mass congestion and congregation—on the subway or the beach, in nightclubs or breadlines—stage the interracial negotiations that were increasingly understood as a key feature of modern urban experience. Vividly contextualizing the works in the visual field of the period, she teases out the meanings of ‘blackness’ they encode, unfolding a variety of power dynamics, libidinal investments, essentializations, and performances on the parts of both the figures in the paintings and their creator. The Urban Scene is a powerful exegesis of the contemporary pleasures, dangers, and potentialities of reading race.”

“A fine addition to our understanding of race (and gender) as elements in the artistic representation of urban America.”

Carmenita Higginbotham is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Virginia.

Table of Contents

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 The Urban Artist

2 Reading Public Spaces

3 Girl Watching in the City

4 The Art of Slumming

5 Seeing Poverty

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

In the fall of 1934, Walter White, director of the NAACP, penned a brief but sincere note of gratitude to the urban artist Reginald Marsh. In it, White expressed his appreciation for the artist’s recent donation to the organization’s Fifth Avenue offices in Manhattan. “My dear Mr. Marsh,” he wrote,

It is difficult for me to adequately express our gratitude to you for giving us the original of your drawing, “This is Her First Lynching.” We are having this framed suitably and are placing it in our office here as the nucleus of a collection of drawings dealing with lynching. Your drawing is, in my personal opinion, the most effective one I have ever seen. I have taken the liberty of recommending it to the Pulitzer Prize Committee. I do hope my own admiration will be shared with the members of the Award Committee. Ever sincerely, Walter White.

White’s ardent response to Marsh’s drawing came shortly after the image first appeared as a full-page illustration in the New Yorker (fig. 1). It features a quiet group of figures garbed in work boots and wide-brimmed hats gathering for an evening event. Staged in the immediate foreground, the crowd turns collectively so that faces and gazes are directed to the left of the composition, just outside the picture’s frame. Near the back of the crowd, an older woman with wide eyes and a garish smile holds a contemplative child aloft while remarking to the figure behind her, and presumably to us, “This is her first lynching.”

The explicit caption and implicit theme of the work account for White’s enthusiastic praise for its compatibility with the NAACP’s social and political agendas. The image certainly had value to White, who, seeking the attention of 1930s viewers, republished the image in the African American journal Crisis and then featured the work in an art exhibition in New York within months of its acquisition. Importantly, Marsh’s image gestured to the state of contemporary race relations, in which the subjugation of African Americans had defaulted once again to a system of physical violence and the placement of black bodies on visual and at times graphic display. By the early twentieth century, the black subject was visualized within the context of lynching not only in souvenir photography but also as political propaganda that used African American figures to sway the sympathies of wealthy white patrons.

Still, White’s insistence that Marsh’s drawing was “the most effective one” that he had ever encountered urges us to question how the work operates and invites us to consider its intended audience—New Yorkers who had developed their own processes for interpreting black bodies in the public sphere. After all, “This Is Her First Lynching” is hardly an archetypal lynching scene. It offers little in the way of pictorial incident; we see only a lush tree pictured in the background, a lone farmhouse, and a staid crowd whose reserved expressions reveal scant detail about the activity unfolding beyond the audience’s purview. It is an image about black bodies in which the black body is absent. The allusion to an African American figure lends the work considerable psychological power, and, simultaneously, the black body’s implied presence provides context that optimizes the drawing’s legibility. Here, African American identity is divorced from the visible body, and without visual markers that depict the act of lynching, interpretation moves back and forth between the drawing’s pictured figures and its implied subject. Whatever the political and pictorial efficacy White locates in Marsh’s work, in the end it is a picture produced for an urban audience—magazine readers of the New Yorker and exhibition attendees in Manhattan—that portrays white viewers looking at a raced body.

Such pictorial and interpretive complexities regarding racial representation characterize Reginald Marsh’s pictures of African Americans, and they speak to the rhetorical importance of the black body for urban audiences during the 1930s. As with Marsh’s image, this book is about raced bodies, but even more it is concerned with urban audiences looking at raced bodies. It engages the work of Reginald Marsh to highlight the manner in which urban viewers were exposed to and invested in racial representation. This book argues that black figures acted as substantive cultural and visual markers in American urban art of the 1930s. Between the world wars, black figures manifested complex concerns about race in the city as American artists responded to a new convergence of African American representation—the increased visibility of blacks, as well as new representations of African Americans—and public perceptions of urban culture.

As the foremost artist of the urban scene, Marsh produced titillating images of New York City that traded on an emergent definition of “urban” as a racially integrated space, and one deeply entangled in mass culture. Through a distinctive pictorial vocabulary culled from popular culture and from his own set of recurrent motifs, Marsh engaged with mainstream culture’s attempts to define the country’s changing urban and ethnic landscape. Several of the images Marsh produced in the 1930s contained black bodies; African American figures appeared frequently in his works, including his most prominent paintings, from Why Not Use the “L”? (1930) and Savoy Ballroom (1931) to Negroes on Rockaway Beach (1934) and Sandwiches (1938). In those ten years, Marsh created more than forty paintings featuring working-class black figures.

Racial representations recur throughout the history of American art; however, critical discourse about the depiction of black bodies often defaults to typologies that stress cultural hierarchies between racial and ethnic groups. Within this paradigm, racial language affirms the position of whites as superior to all other racial identities by relegating blacks to the lowest level of the social scale. Certainly, the introduction of figures such as the mammy, the Zip Coon, and the tragic mulatto in nineteenth-century American popular culture relied on specific pictorial tropes to condense the broad and diverse history of black cultural experience into stock characters. Equally true, the circulation of these images worked to reinforce the white mainstream’s sense of the inherent inferiority of blacks, further justifying processes of social and political control. The reliance on such critical frameworks, however, perpetuates what Valerie Smith describes as inaccurate binaries in discourse concerning strategies of black representation, and it presupposes a direct relationship between representation and real life. Moreover, these binary frameworks resist processes of subjectification; they deny mechanisms through which the individual subject is constructed—a construction made possible through the use and deployment of racialized language that underlies relations between black and white.

In the 1930s, black and white artists, writers, and other cultural producers competed for the authority to define the language of racial representation. Marsh himself exploited a range of pictorial techniques, including caricature, old master drawing styles, and politically charged visual tropes, to interpret the black urban presence. If the language of race, as Stuart Hall asserts, is a discursive formation that binds culture and representation, then Marsh’s use of African American figures reveals how urban sites such as New York construct meaning about and through urban black bodies. As an articulation of difference, racial language operates as part of a classificatory system that constitutes culture. It marks and codifies otherness, it constructs symbolic boundaries meant to regulate cultural order, and at the same time it generates and facilitates desire for that which is forbidden or taboo.

Within the various maneuvers that the language of race undertakes in American visual practice in particular and Western representation more broadly, it most often has been understood in relation to the body. The assignment of race to the physical form naturalizes difference and suggests that the mark of racial otherness is tantamount as evidence of biological, social, and cultural inferiority. Importantly, the language of race is at once familiar and elusive. Certainly stereotype was and remains the most prominent form of racial discourse about African Americans, as it essentializes identity in order to codify authority, fantasy, and desire. Yet, as Homi Bhabha has argued, stereotype also requires ambivalence in order to retain its prescriptive power over a range of generations and across geographical locations. This “floating signification” of race, at once relational in its meaning and in constant flux, allows for investigations into how the deployment and reception of images shift within cultural moments or periods.

It is a critical task, then, to examine the ways in which these pictorial types and other forms of representing the black subject perform cultural work. The black bodies pictured by Marsh engage a series of conditions—the images’ intended audiences, the environment in which the representations were created, the assumptions about the artist producing the work—that determine how such images would have been read. In settings such as Coney Island, Harlem, and the subway, difference reveals itself to be contingent on what Mary Bucholtz and Kira Hall describe as a “phenomenological process that emerges from social interaction.” The black bodies Marsh depicts are in a constant state of redetermination based on a series of relational conditions—namely, how they are pictured together with other urban bodies, both black and white, and what they are pictured doing. Significantly, the limits of these interactions are largely determined by the social rules concerning visibility and interracial contact that were established for a wide range of popular urban spaces—from beaches to subways to movie theaters—in the interwar years. Thus, whatever else they are, Marsh’s images are statements of hierarchy and power, testaments to the ways in which race functions as a technology that “organizes and manages populations in order to obtain certain goals.” In the words of Dan Swanton, they emphasize “what race does in interaction” to reveal how differentiation is formed and performed.

American art historical scholarship has argued that the construction and deployment of racialized visual language served as a method both to question the appropriateness of black bodies in the national body politic and, conversely, to help determine pathways for their inclusion. Recent studies have qualified these discussions by asking how representations of African Americans during the “long” nineteenth century reveal the transitory nature of racial identities and the manner by which blackness has been “unfixed” from the body. For African American artists, this included expanding their own methods of representation to claim aesthetic agency over the mechanics of racial expression. Strategies adopted by Marsh and his urban contemporaries relied on coexisting and at times competing impulses. On the one hand, popular visual practices used the black body to signal broader cultural investments in modernity and the city. On the other hand, representation worked consistently to identify and contain black bodies whose very appearance disrupted boundaries of aesthetic decorum and political agency.

By locating the cultural work performed by racial representation at the center of scholarship about Reginald Marsh, I address the interpretative challenge that his images of the black subject present to art historians. Few scholars have produced critical work on Marsh, and none center their inquiry on his African American figures. Critical writing on Marsh in the 1930s and 1940s differed little from early interpretations of his work by art historians in the 1970s. Both attribute the diversity of the artist’s subject matter to his commitment to pictorial realism and his urban residency. Racial difference thus exists to articulate the “vitality, humor and a capacity for enjoyment” common among his pictured working classes. More recent surveys of Marsh’s artistic practices, examining his method of production and his artistic style, laud his work for its illustrative qualities, as it captures “what was newest on the urban scene.” In the end, these studies, while important to the expansion of critical interest in American art of the 1930s, reinforce a direct and fundamentally flawed alignment of realist technique with social reality, one that overlooks Marsh’s use of caricature and stereotype. As Phoebe Wolfskill has noted, physical distortion exists within Marsh’s realist enterprise as a concerted response to modern life as “inherently complicated, open-ended, and destabilizing.”

Gender has proven to be the most active arena in which scholars have reassessed the importance of discursive meaning within Marsh’s aesthetic enterprise. Ellen Wiley Todd’s study of pictorial strategies in the work of Marsh’s professional cohort, known as the Fourteenth Street school, explicates how the dispersal of female figures depicted through the adoption and adaption of popular visual tropes expressed changing social and cultural ideologies between the two world wars. Further, these figures, as sexual caricatures placed on display in shop windows and burlesque dens, facilitated movement within the cityscape, especially of middle-class audiences enjoying the pleasures of lower-class leisure. Thus far, investigations focused on how these artists employed popular visual language to represent a modern, urban body have been limited to the exploration of identities designated as both female and white.

I aim instead to explore how African American representation exists within and creates discursive spaces that respond to a growing interracialism in American cultural production and in the spaces of the American city. Working-class urban “blackness” stands as a critical and multivalent concept in my discussion of the interwar period for its suggestion of a racial status and cultural attitude that black and white audiences recognized, adopted, and intermittently rejected. The mechanisms for its use fuel this book’s historically specific investigation of the ways in which “black” signified in New York in the late 1920s through the mid-1930s, when art, advertising, theater, and film all served as cultural sites that attempted to delineate and codify blackness. Underlying the pleasures of jazz music, Negro stage performances, and integrated nightclubs were latent anxieties about racial transgression or “passing,” and the frequent inability or failure of vision to locate urban blackness. Definitive pictorial criteria for identifying blackness in order to demarcate and preserve racial categories proved elusive, and Marsh struggled, as did many artists of the period, with how to represent blackness and where, if at all, signs of blackness should be fixed: on the body (skin color, bestialized features), elsewhere in the painting (setting, narrative), or even in the removal of the black figure altogether.

If racial language dictates the method by which I approach Marsh’s representations, then the city provides a frame through which interpretations of the black body are distilled. The representation of urban spaces often collapses into the representation of “the city”—a symbolic construct of an aggregate of visual, spatial, and experiential details reduced to a single entity—and as a result suggests (inaccurately) coherence. As Marsh’s representations of the black urban subject articulate, there is an inherent instability in its promises of legibility and visibility—promises further confounded by urban representations’ own claims to offer a readable scoring of the city. The competing ways in which race is or can be engaged through the lived experience of urban spaces and in their representations produce multiple access points for interpretation. Sensitive to popular urban locales and the dynamic interplay between people and the city, Marsh’s imagery emphasized the importance of place and location, the establishment of boundaries, and the racial definition of physical space. His paintings of black figures on the subway, at Coney Island, in Harlem, or in the Bowery construct a means for deciphering New York’s shifting urban culture through the presentation of public, racialized space and, importantly, respond to contemporary discourses of urban space, social order, and the negotiation of the presence of African Americans in the 1930s.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.