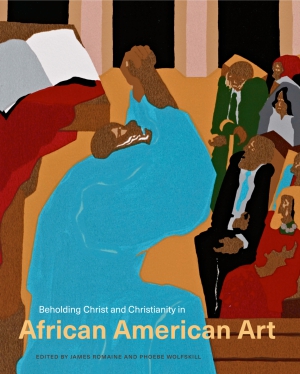

Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art

Edited by James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill

Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art

Edited by James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill

“An innovative collection. . . . The complex reality of African American religious art is revealed as a powerful witness of artistic and religious diversity. Highly recommended.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Focusing on the work of artists who came to maturity between the Civil War and the Civil Rights Era, the contributors show how engaging with religious themes has served to express an array of racial, political, and socio-economic concerns for African American artists. Through a close analysis of aesthetic techniques and choices, each author considers race but does not assume it as a predominant factor. Instead, the contributors assess artworks’ formal, iconographic, and thematic participation in the history of Christianity and the visual arts. In doing so, this collection refuses to lay a single claim on black religiosity, culture, or art, but rather explores its diversity and celebrates the complexity of African American visual expression.

In addition to the editors, the contributors are Kirsten Pai Buick, Julie Levin Caro, Jacqueline Francis, Caroline Goeser, Amy K. Hamlin, Kymberly N. Pinder, Richard J. Powell, Edward M. Puchner, Kristin Schwain, James Smalls, Carla Williams, and Elaine Y. Yau.

“An innovative collection. . . . The complex reality of African American religious art is revealed as a powerful witness of artistic and religious diversity. Highly recommended.”

“Essential reading for anyone in the fields of Christianity and the arts or African American studies.”

“A persistent alchemy of transforming the Christianity of African Americans into cultural politics has long complicated the important task of understanding the hold that religion has had in the life and art of American blacks. The contributors to this book have joined together to correct this, producing a fascinating and highly enjoyable volume that investigates art and religion together, grounding their efforts in the historical moments of important careers and cultural eras that have shaped an estimable legacy. The result sheds new light on impressive bodies of work, allowing us to see anew what was always there.”

“This volume constructs a social history of African American culture’s use of Christian texts, images, and symbols and offers readers concrete examples of just how rich and varied the uses of Christian discourse have been. Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art is a unique, remarkable, and fascinating text that makes an enormous contribution to the scholarly conversation on religious discourse.”

James Romaine is Associate Professor of Art History at Lander University in Greenwood, South Carolina. He is president and co-founder of the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art. His most recent book is Art as Spiritual Perception.

Phoebe Wolfskill is Assistant Professor in the Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, and author of Archibald Motley Jr. and Racial Reinvention.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction: Hidden in Plain Sight—Christ and Christianity in African American Art James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill

1. Propaganda Fide: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Catholic Church Kirsten Pai Buick

2. Reading Tanner/Recognizing Jesus James Romaine

3. The Blare of God’s Trombones: Modernizing Biblical Narratives in the Work of Aaron Douglas Caroline Goeser

4. The Sight of Black Folks: Malvin Gray Johnson’s Spiritual Paintings in Interwar America Jacqueline Francis

5. Christianity and Class in the Work of Archibald J. Motley Jr. Phoebe Wolfskill

6. The Aesthetics of Transcendence: William H. Johnson’s Jesus and the Three Marys Amy K. Hamlin

7. Sculpting the Spirit and the Flesh: The Religious Works of James Richmond Barthé James Smalls

8. Allan Rohan Crite’s (Re)Visioning of the Spirituals Julie Levin Caro

9. Sister Gertrude Morgan and the Materials of Visionary Art Elaine Y. Yau

10. “A Tried Stone”: Community, Conversion, and Christ in the Sculpture of William Edmondson Edward M. Puchner

11. Biblical and Spiritual Motifs in the Art of Horace Pippin Richard J. Powell

12. Assimilation and Aspiration: The Urbanity of Faith in James VanDerZee’s Representations of Religion Carla Williams

13. Deep Waters: Rebirth, Transcendence, and Abstraction in Romare Bearden’s Passion of Christ Kymberly N. Pinder

14. Creating History, Establishing a Canon: Jacob Lawrence’s The First Book of Moses, Called Genesis Kristin Schwain

Selected Bibliography

List of Contributors

Index

From the Introduction

“Hidden in Plain Sight:Christ and Christianity in African American Art”James Romaine and Phoebe WolfskillIn a 1933 work Self Portrait (Myself at Work), Archibald J. Motley Jr. surrounds himself with attributes that portray his personal and artistic identity (figure I.1). The nearly completed painting of a lush nude, a classical statuette in the foreground, and a plaster mask that Motley would have copied during his study at the Art Institute of Chicago, all reference the artist’s abilities and academic training. The directness with which Motley addresses the viewer recalls his earlier self-portrait, circa 1920; however, the 1933 work incorporates objects that speak more specifically to his artistic mastery, communicating the confidence that followed a decade of notoriety as a central artist of the Harlem, or “New Negro,” Renaissance. Motley notably includes a crucifix behind him on his studio wall. In tandem with the secular studio props, the crucifix conveys the complexity of Motley’s identity as an artist, an African American, and a Catholic. Motley’s work visualizes a gap in our conceptualization of African American art; like the crucifix in his Self Portrait, the presence of Christianity in the work of many African American artists is hidden in plain sight. In the history of African American art, commentators often overlook the multiple factors that contribute to an artist’s sense of self, and particularly one’s relationship to religious faith, due in part to a heightened focus on racial iden¬tity. As the artists examined in this anthology prove, however, Christianity and the visualization of Christian themes are a central component of this history. By exploring the unique relationship between specific artists and their engagement with Christian subjects and references, Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art develops a vital conversation regarding the place of Christianity in American art and the complexity of African American visual expression, which is inevitably informed not solely by racial identity but by the many influences that shape selfhood and artistic communication.Motley’s conspicuous reference to his Catholic faith in his Self Portrait brings a number of questions into focus. What does it mean for an African American artist to identify and be involved with the Catholic Church in Chicago in the early twentieth century? How does exhibiting his Catholic affiliation underscore his relationship to a larger community bound by religious faith, whether white, black, middle class, working class, or other categories? In what ways does Motley’s religious affiliation influence his approach to art and artistic vision? Motley’s subtle yet significant inclusion of a crucifix invites a wealth of queries that inspires viewers to probe deeply into the artist’s identity and conception of self. At the same time, it encourages consideration of the ways in which Motley’s religious alliance places him in relation to broader social and artistic communities and cultures.

In her study of race and American modernism, art historian Jacqueline Francis notes the limited perceptions of religious work by Harlem Renaissance artist Malvin Gray Johnson, remarking on the commonplace understanding of African Americans as “America’s most pious Christians.” Exploring this long- standing assumption of the relationship between blackness and Christian devotion reveals its obvious narrowness, yet this conception has frequently prevented a closer engagement with the association between black identity, faith, and artistic expression. Furthermore, as Francis questions, in relating racial identity and religion, is a reference to Christian subject matter solely a reflection of piety? Beholding seeks to broaden and complicate the relationships between African American artists and Christian subject matter by exploring how the artist’s engagement with religious subjects, symbols, or themes can be an expression of an array of concerns related to racial, political, and socioeconomic identity as well as social and artistic community, audience and art market, and formalist experimentation.Beholding, therefore, advances the art historical discourse by integrating religion and race into the matrix of factors that influence art production, use, and interpretation. Many of the most celebrated African American artists have created works of art that visually manifest overt Christian motifs and themes. In much of the scholarly discussion of these works, Christian subjects have been primarily examined through methodologies that foreground issues of race. In spring 2003, American Art published a dialogue among notable contemporary scholars of the field about the state of African American art history. In his contribution, James Smalls calls for multiple theoretical models and methods for addressing African American art in order to recognize its art historical significance and broaden and complicate the established but often delimited field. Smalls writes that one must “transform it [African American art history] from a moribund field of special interest and fixed concepts into a vital terrain of lively and contested ideas.” In his own work, Smalls enriches the discipline by considering the ways in which issues of gender and sexuality, alongside race, inform an artist’s visual strategies. Beholding adds religion to this discussion as a strategy of further expanding the field. How does one understand these works differently when one measures them with methods that emphasize their formal, iconographic, and thematic participation in the history of Christianity and the visual arts in a manner that considers race, but never assumes racial identity as a sole or even primary factor? A close analysis of these aesthetic techniques and choices is fundamental to this anthology.

Cultural theorist Kobena Mercer writes, “Despite the welcome proliferation of surveys and monographs in recent years, the black art object is rarely a focus of attention in its own right.” Indeed, scholarship on African American art advances only if one evaluates black artistic production as consisting of objects meaningful beyond statements of identity and culture and worthy of rigorous formal evaluation. The artists featured in this anthology, whether academically trained or self- taught, visionary or matter-of-fact in their approach to Christian themes, construct objects that have visual and often tactile power that activates the intellect, emotions, and perception of the viewer. The chapters in Beholding thus raise the following question: how does one visualize a Christian theme or symbol in a manner that serves didactic or illustrative purposes while simultaneously underscoring the power of visual art to provoke religious devotion? Alongside stressing the practical, aesthetic, and interpretive decisions artists make in constructing a particular work, the contributions in this volume consider the broader social and cultural context related to racial, class, and gendered identity as well as geographical region. These contexts are then deepened by considering the artist’s intended audiences and the nature of those audiences’ expectations and desires.

Racial identity and what it signifies are forever elusive. In exploring the complication of racial labels and affiliations, literary scholar J. Martin Favor writes, “Blackness is constantly being invented, policed, transgressed, and contested.” To deal in any way with “African American art” is to necessarily engage the paradox of identity: to label an art as “African American” assumes a communal identity that can severely limit the truth of individuality; yet by engaging racial identity, this anthology seeks to explore the ways in which it was meaningful or relevant to the artists and contexts under examination. Because Beholding examines artists whose mature work dates from the Civil War through the civil rights movement (ca. 1860s–1960s), the artists’ identity as black Americans carried specific cultural inferences at the time they were producing art.

Being African American within this period highly influenced how an artist’s work was framed and interpreted and how the artist might negotiate his or her relationship to racial identity. Many would argue that this endures in current discourses. Bringing together a group of “African American” artists is inherently problematic and limiting, yet it can be enlightening and strategically necessary. The artists included in this anthology respond to their own conceptions of black identity as structured from within and without. Individually, they may cultivate or choose not to engage black identity or a broader black community. Yet inevitably they had to contend with the racial constraints, restrictions, and limitations of museum, gallery, and educational institutions; the discipline of art history; and American society more generally. While these conditions may have limited the discourses and places in which these artists’ works were initially discussed and displayed, they also afforded artistic opportunities for creative forms of expression, the circulation of new art and ideas, and conceptually and formally innovative counternarratives of Christianity. This anthology takes into account race as a factor in the articulation of Christian subject matter, but not the only factor. Gender, class, geography, historical period, and background, among other considerations, all come to the foreground in this book as a means of historicizing and contextualizing the artists evaluated. The chapters thus bring about a deeper understanding of the artists’ work, identity, and methods of visualizing Christian subjects and symbols.

The assortment of media studied in this collection not only undermines high/low distinctions but also makes clear that African American artists mastered a broad spectrum of artistic creation, from highly academic work, to modernist approaches, to more intuitive and often highly inventive forms of expression. This definition of art includes a broad range of media and methods. Two-dimensional media consist of paintings of oil on canvas or gouache on paper, brush and ink drawings and drawings with crayon and ballpoint pen on cardboard, and photography. Sculpture includes objects cast in bronze and carvings in marble and stone. Created by artists trained in academic traditions as well as untrained and “visionary” artists, these works diverge stylistically and conceptually. This wealth of materials and methods demonstrates the diversity of visualizing Christianity, complicating how one views African American art and responds to visual expressions of faith. By devoting each chapter to an individual artist and his or her method of addressing Christian motifs, Beholding reveals a range of visual methods and conceptual relationships to these subjects and thereby deepens how one views and understands Christian and African American art.

This anthology underscores that the artist’s visual articulation of faith and religious practice is no less complicated than his or her representation of race. In many ways, a person’s faith in, or doubt of, God is among one’s most intimate beliefs. For many artists, their creative process is a means of working out and articulating their convictions. At the same time, religious practice functions as a broader reflection of identity as social, racial, communal, and otherwise. Specific Christian faiths, whether Baptist, Episcopalian, Holiness, Methodist, Roman Catholic, or other denominations, are contextualized by each author in terms of specific historical moments, geographic regions, and socioeconomic foundations. In this way, this book does not analyze one single relationship to religiosity. By eschewing essentialist or limited definitions of Christianity, African American identity, or even “art,” this collection opens up a discussion of the complex and interwoven relationship between artist, faith, identity, and community.

The author of Proverbs 29:18 wrote, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” The chapters in this anthology explore whether the inverse is also true: “where there is vision, the people persevere.” Such a reading views the work of art as a realization of and instrument for a personal, social, and/or spiritual vision. Although the term visionary is often narrowly applied to the works of nonformally trained artists who view their work as the visual expression of a divinely inspired vision, Beholding addresses works of African American art as a realization of and catalyst for transforming vision itself. The artworks discussed herein thus function as a channel for the artist’s self-reflection and his or her relationship to Christianity while stimulating the viewer to contemplate the same.

Christianity was founded in the first century by apostles of Jesus Christ. Christians embraced the accounts of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection described in the Gospels of the New Testament. Many early Christians were converts from Judaism who interpreted the Jewish scriptures, the Old Testament, as prophetic of Christ. In the eleventh century, Christianity divided into the Orthodox Church, then centered in Constantinople, and the Catholic Church, led by the Papacy in Rome. Orthodox liturgical practices include the veneration of icons, nonpictorial and even miraculous images of Christ, his mother Mary, and Christian saints. The Catholic Church repudiated the veneration of icons but did adopt the use of art in church worship and has been one of the single most important patrons of the visual arts. In the sixteenth century, the Protestant Reformation broke away from the Catholic Church. While Protestant reformers disavowed, and even destroyed, images and objects intended for use in worship, Protestant artists have created works theologically consistent with an emphasis on each person’s individual spiritual relationship with God.

(Excerpt ends here.)

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.