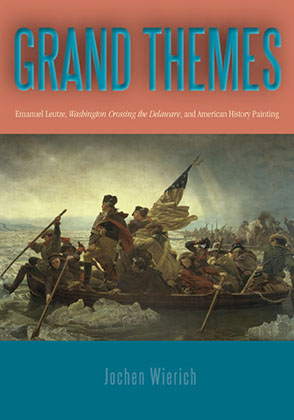

Grand Themes

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, and American History Painting

Jochen Wierich

Grand Themes

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, and American History Painting

Jochen Wierich

“Grand Themes: Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, and American History Painting brings to this topic a wide-ranging and critically informed historical lens—as well as a thoughtfulness and thoroughness—that it has never before received. What is ultimately at stake in this study is the time-honored hierarchy of the genres, in a day and place in which that hierarchy put forth, as the author puts it so well, ‘a sham form of cultural authority.’”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Grand Themes: Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, and American History Painting brings to this topic a wide-ranging and critically informed historical lens—as well as a thoughtfulness and thoroughness—that it has never before received. What is ultimately at stake in this study is the time-honored hierarchy of the genres, in a day and place in which that hierarchy put forth, as the author puts it so well, ‘a sham form of cultural authority.’”

“This fascinating and richly detailed historical study explains how the legendary painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, a sensation at its first public showing in 1851, provided antebellum Americans with a message of hope and unity at the very moment their nation was crumbling—and how, once civil war became inevitable, art of such immense size and unmitigated idealism lost its magnetic power. Jochen Wierich examines alternative types of history painting that emerged during the period and analyzes the critical debates they fueled. In doing so, he dusts off a neglected genre of American art and makes us see how crucial it once was in defining the country’s present by picturing its past.”

Jochen Wierich is Curator at Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The Look of History

1 The Revolt Against the Grande Machine: Emanuel Leutze at the Metropolitan Fair

2 Leutze’s Storming of the Teocalli: Historical Struggle and the Middle Class

3 A Republican Court for the American People

4 Painting for the Union: Lilly Martin Spencer’s War Spirit at Home

5 Eastman Johnson: Low Life and “High Art”

Conclusion: History Painting and the Centennial

Notes

Index

Introduction

The Look of History

Give us a chance, our history is the history of the liberty—the history of a struggling world for more than three centuries—not confined to our own shores we seek the causes of our institution in every clime where oppression has been, where noble man broke a tyrants chain or sought refuge from it by braving the ocean and an unknown wilderness. The scenes that rise before the historians eye are vast and grand—what must they be to the artist.

—Emanuel Leutze to Montgomery Meigs, 1854

This book is concerned with changing visions of history and historical narrative in American art. During the middle decades of the nineteenth century, Emanuel Leutze dominated the field of history painting with grand and epic canvases that represented important historical characters and events. Writing to a government representative to lobby for a mural painting for the U.S. Capitol, Leutze gave an expansive and ambitious account of his own vocation. The history of the United States was a three-hundred-year struggle for liberty that, to Leutze’s mind, constituted a basic condition for the “institution” of a democratic society. In 1854, the struggle was still unfolding before the history painter’s eyes, an endless drama that would provide the artist with the material for grand historical scenes.1 For Leutze, the historical artist’s calling was to paint such themes and historical actors in pursuit of noble causes; and there was no more exalted place in America to paint the history of democracy, liberty, and world struggle than the Capitol Rotunda.

Leutze’s hope rested on the notion that a great nation simply deserved great historical art (in this he anticipated the National Endowment for the Arts’ current slogan, “A Great Nation Deserves Great Art”). But he invested his efforts in a genre that was struggling, especially as an enterprise that received public support through government patronage. Even on a nongovernmental level, Leutze’s vision of history painting as the art of grand themes, the pursuit of noble causes, the story of heroic individuals struggling against the forces of oppression, faced challenges. Throughout the middle decades of the nineteenth century the American art public was unsure of the proper role of historical art, as the nation struggled with its own divisions and historical shortcomings. On the surface, history painting was still a dominant mode of historical representation, and Emanuel Leutze was its most prominent practitioner and spokesman. Yet Leutze became a target for many detractors who advocated a new kind of history painting, and his demise became emblematic of the entire genre. In this study I am particularly interested in Leutze’s career, as it epitomizes the erosion of history painting as a valued and commonly shared form of historical memory.

I focus on Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware not only because Leutze’s reputation as an epic history painter still rests on this painting but because it is the great monument that this German-born artist gave to his adopted country, and American culture has had to grapple with it ever since it first crossed the Atlantic Ocean. It is the painting that generations of Americans have grown to love or hate. For most of its life, it has sat uncomfortably in American culture. The art world has never quite taken it seriously, and it has been parodied over and over again, while historians of the American Revolution have embraced or debunked it. The debate over its reliability as a historical document continues today. Washington Crossing the Delaware is a kind of leitmotif that runs through this book, but it also recedes into the background as the argument unfolds.

In Leutze’s plan to receive a government commission, Washington Crossing the Delaware was the crowning achievement, the summa of a historical narrative that he had outlined in his letter to Montgomery Meigs, the chief architect of the Capitol. After painting it in Düsseldorf, Germany, Leutze sent it on a tour of the United States in 1851 in the hope that it would get him a commission for the U.S. Capitol. His purpose was to invent a heroic painting that would help him clarify his grand historical scheme. Despite the waxen, tableau vivant appearance of Washington (modeled after a bust by Houdon) and his troops (the artist Worthington Whittredge and others served as models in Leutze’s Düsseldorf studio), Leutze rendered the famous crossing on Christmas night 1776 with romantic drama. The scene was designed to lift viewers out of their everyday existence into the realm of grand historical vision. The whole boat and its parts, including the rudder and oars, the bodies of the men, the drift of the current—all point to an imagined shore that stretches from the background into a space beyond the picture. Compactly bunched around their fearless leader, this crew is determined to reach the New Jersey shore and rout the Hessian army. While the outcome of their surprise attack is uncertain, these actors are already destined to propel America onto the stage of world history, their victory a major step toward nationhood. Washington’s leg is thrust out, and his saber, polished and almost long enough to be a third leg, adds to the general’s monumental stature and sense of purpose. Following the vertical, upward motion of Leutze’s Washington, the viewer’s vision is again pushed outside the pictorial space. The various vertical lines that make up the central pyramid of the composition, including guns, bayonets, and the pointed end of the flag, all thrust the viewer’s eye above and beyond the upper border. The monumental figure of Washington himself is transformed as his body is mirrored and further elevated by the billowing flag. Although the event takes place at the viewer’s eye level, and the scene is painstakingly re-created in historical detail, the viewer’s historical gaze is extended beyond the visible. What Leutze constructed in word and image was a historical vista, an extended historical view that was boundless. If ever historical struggle had meaning and purpose, the arduous crossing of the Delaware that became the turning point in the American Revolutionary War had it all.2

Especially on a metaphorical level, Washington Crossing the Delaware was a painting that could easily win the admiration of the American public. It could, in a sense, resuscitate a struggling genre. This is not the place for a complete historical survey of the genre in America during the six or seven decades leading up to the 1850s, but there are many scholarly works on the kind of historical art that was produced in the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Decades before Leutze, Benjamin West and John Trumbull had introduced models for painting war, revolution, and heroic sacrifice, namely, through painting in the Anglo-American grand style. Writing for the exhibition catalogue Picturing History: American Painting, 1770–1930, art historian Ann Uhry Abrams has discussed the four mural paintings of the American Revolution by Trumbull that were installed in the U.S Capitol Rotunda between 1818 and 1828. All four depicted history as an orderly process, seen, for instance, in the Declaration of Independence and General George Washington Resigning His Commission (1824), as well as in two scenes of the British surrender at Saratoga and Yorktown. In their solemnity, these paintings posed questions about how history painters should best address the history of a nation that had made the transition from war to republican government.3 As Wendy Greenhouse explains in the same catalogue, American painters continued to search for quintessentially national themes in history but found a paucity of subjects. In addition to the ever popular Washington, as seen in Thomas Sully’s Passage of the Delaware (1819), they turned to themes of the “original moment,” including “dramatic departures, landings, arrivals, and discoveries.” The principal heroes in these dramas were the Pilgrims, Christopher Columbus, Henry Hudson, and other explorers and discoverers, many of them figures that linked the Old World with the New. As Greenhouse points out, American artists, including Leutze, also showed great interest in British Tudor and Stuart history. British history was morally instructive, since it contained episodes of religious persecution and often put women at the center of political power struggles, thus providing a moral lesson for Americans and a counterpoint to how they envisioned their own national destiny. By the 1850s, according to Greenhouse, history was a national “obsession, object of veneration, or mode of perception,” yet history painting, especially in the grand style, was still in the process of legitimizing itself.4

During the antebellum period, history painters were already avoiding what Greenhouse calls the “patriotic bombast” represented by Washington Crossing the Delaware and were painting scenes that were more like genre painting.5 The historical genre was even pursued by artists who had larger ambitions for history painting, including Leutze himself. As the art historian Mark Thistlethwaite has argued, genre and history painting merged during the antebellum period, and history was downsized into “smaller-sized compositions, smaller-scale figures,” and appeared in “incidents rather than major events.”6 The scholarship on historical art keeps expanding the canon, and definitions are always subject to revision. In selecting essays for their anthology Redefining American History Painting, Patricia Burnham and Lucretia Giese deliberately probed the boundaries of what constitutes historical art, including chapters on George Caleb Bingham, Thomas Eakins, and Frederic Remington. In order to include the range of historical art that their book discusses, Burnham and Giese offer a helpful framework of three components that underlie the inner workings of history paintings: historicity, narrativity, and didactic intent. Put in very simple terms, historicity describes the correlation between history painting and historical fact. This category is important in establishing a painting’s authenticity. Narrativity is the crucial art of persuasion that every historian, painter, and writer must master in order to tell the story well, to present the historical event in a continuum of causality. It is with didactic intent, finally, that the historical painting can teach, convince on an ideological level, and find a moral center.7 While this definition of history painting is very open-ended and allows many different forms of painting to coexist, I would argue that during the middle decades of the nineteenth century much was at stake for a grand national painting such as Washington Crossing the Delaware. Indeed, it is the cultural context of history painting and its gradual transformation during this period that is the subject of this book. What I offer are case studies of artists who developed alternative historical images in response to a crisis in history painting that took shape in the antebellum period and became more pronounced during the Civil War.

As Lucretia Giese has argued persuasively, the Civil War posed an almost insurmountable challenge for history painters. A modern war that was so protracted and chaotic in its totality, that so divided the nation into sections and then into factions, was, as Giese puts it, “pictorially awkward” and impossible to depict “in terms of conventional history painting.”8 It is important to note that Leutze painted the largest painting of his career, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, during the Civil War, and he planned to paint more historical scenes related to the war, but he died before he could finish them. There was a different mood in the art world after the Civil War, and it is symptomatic that one of the most successful paintings of the period, Winslow Homer’s Prisoners from the Front, is so “matter-of-fact-looking” that it largely conceals its own historicity and moral intent.9 Had Leutze lived longer, he would certainly have witnessed a larger critical shift and erosion of support for his epic canvases and the philosophical charge behind them. In 1866 one critic described a very different course for the genre: “Historical art . . . is good when the artist is at home in, and strongly impressed by, the scenes he delineates; the truest and therefore the most valuable historical art being the record of what the artist sees and knows in his own time,—events that happen around him, events of which he makes part.”10 In other words, paint the scenes that you and your audience are familiar with, scenes that are outside the realm of historical fiction and larger-than-life heroes.

By juxtaposing Leutze’s earlier statement with that of a post–Civil War critic, we can see the credibility problem that emerged once an artist’s vision got out of step with historical reality. After the Civil War, the lofty goals that Leutze envisioned for historical art lost their conviction; artists now had to respond to a shift in taste from the grand to the small, from the ideal to the real. As announced by the anonymous critic quoted above, the historical art now considered best was concerned with contemporary events, personal experience, and eye-level exactitude; in short, the artist was expected to be “at home” in history. This critic captured perfectly a process that I refer to as the domestication of history. What I investigate in this book is how the voices of the artistic marketplace—producers of historical images, critics, patrons, and the larger art-buying public—contributed to this domestication and shaped the look of history during the middle decades of the nineteenth century.

Although the Civil War was a shattering event for history painting, the broader crisis of the genre and the reasons for its collapse predate the war. Mark Thistlethwaite and others have described in detail how the figure of Washington was domesticated in American art.11 One might argue that Americans have always been reluctant to embrace their most revered leaders as demigods. Writing about American attitudes toward history during the antebellum period, Michael Kammen has attributed “American indifference to the past” to “pluralism (a diverse society that shared a future but not a common history); physical and social mobility; and the pervasive belief that government ought to bear little responsibility for the maintenance of collective memories.”12 In other words, historical monuments were a distraction, if not a burden, for a people focused on living in the present. To put it more cynically, the young American democracy was guilty of historical apathy. Yet there were many signs of an awakening historical consciousness during the antebellum period. Civic leaders in cities from Boston to Baltimore and Washington, D.C. erected large monuments to celebrate revolutionary heroes and battles. But the figure of Washington, standing on a 178-foot Doric column in Baltimore designed by Robert Mills, was almost invisible to the viewers below.13 Referring to the Washington Monument in his epic novel Moby-Dick (1851), Herman Melville wrote, “Great Washington, too, stands high aloft on his towering main-mast in Baltimore, and like one of Hercules’ pillars, his column marks that point of human grandeur beyond which few mortals will go.”14 Monuments that soared skyward embodied the historical lessons that epic history had taught for ages. Heroes were demigods. They came down to earth to lead exceptional lives, and after their death they returned to the celestial sphere, where they resided in glory.

The belief that Washington had to be monumentalized for public memory was not universally shared, however. As early as 1808, Washington’s biographer Mason Weems expressed a different longing when he called for a description of Washington’s “private deeds,” for a hero who did not reside above the clouds.15 Americans had various ways of making history more accessible, of shrinking superhuman heroes to a size that fit their private surroundings. The gift-book illustrations and engravings that Americans enjoyed at home were tiny compared to the gigantic columns that dominated their urban spaces. As represented in Francis Edmonds’s genre painting The Image Peddler, peddlers went from house to house selling miniature plaster statues, including busts of George Washington. Edmonds’s genre painting illustrates the process in which “ordinary people” domesticated history, making the gigantic miniature.16 I believe that the tension between these modes of historical seeing—between the monumental and the domesticated—crystallized around the medium of history painting and manifested itself in the larger visual culture.

The basic cultural dilemma that these few examples illustrate continues into the present. In his discussion of Norman Rockwell as an important painter/illustrator of twentieth-century American history, David Hickey refers to Rockwell’s After the Prom (fig. 1), which appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post on May 25, 1957, as a paradigmatic example of history painting transformed. Following Hickey’s interpretation of Rockwell, we can trace the migration of history into a new genre, what Hickey calls “democratic history painting,” which presents history at eye level and thus makes it accessible to ordinary people. According to Hickey, history painting before Rockwell was “faux-democratic.” The formula that Rockwell employed was to take the formal complexity of European history painting and fill the composition with ordinary people, America’s youth, embodied by the girl and boy sitting at a soda fountain in After the Prom.17 The blissful couple, contentedly reveling in the moment, represents an America whose conflicts are all behind it and that can now enjoy its youthful innocence.

<comp: Insert fig. 1, Rockwell’s After the Prom, about here>

The soda jerk and the customer in the bomber jacket, interlocking with the blissful prom couple, make for a benign scene. The pictorial space that Rockwell “invents” is the domesticity of a 1950s American diner, all complex historicity pushed outside the picture frame. The composition tightly controls the viewer’s eye level, narrowing her historical vision. A narrative that focuses on what Hickey calls “living in historical time, growing up, growing old,” naturalizes the narrowed vision and makes history integral to living, organic being. Rockwell’s image thus constructs not only a specific historical scene and viewpoint but also a viewing subject.

Paradoxically, as a closer look at the evolution of the genre in the United States reveals, the so-called death of history painting also contributed to its survival. I believe that the look of history that we find in Rockwell’s painting is convincing in part because of the transformation that took place in the nineteenth century. And I argue that long before Rockwell, the foundations of history painting in the United States began to shift, and the producers and consumers of historical images became concerned with how to domesticate history for the viewing experience of ordinary people.

During the middle three decades of the nineteenth century, from around 1848 to 1876, representations of history were the subject of intense debate, and the nature of “democratic” historical art was often an implicit part of this debate. Americans with an interest in historical art could hardly agree on what a convincing historical painting should look like. Historical art such as Washington Crossing the Delaware provided the public with reassuring examples of an imagined past community, but as an art form, history painting was unable to build a national consensus. History painting was a struggling artistic genre in a changing artistic hierarchy. It never completely disappeared, but it was domesticated in other cultural forms such as genre painting. Genre painters represented the new “historical art,” which was concerned almost exclusively with recent events, ordinary people swept up by historical circumstances, and scenes of domestic life. History painting, which had always ranked as the pinnacle in the hierarchy of genres, now had to contend with new forms of historical representation. The question of how and why this shift came about is a central concern of this book.

The iconography of George Washington is an important subplot in this story, and the civic religion of Washington has many places of worship, from Trenton to Mount Vernon, and it continues to surface in the most unexpected ways. As historians of Washington iconography have demonstrated, while the general was often put on a pedestal, his image was just as likely to reside in the American living room, and Americans visited his bedroom. The “George Washington slept here” phenomenon has taken many directions over time, but it certainly had one point of origin in the house museum movement of the nineteenth century. As several historians have argued, the preservation history alone of the home of George and Martha Washington at Mount Vernon speaks volumes about the cultural process of domesticating history. From Mount Vernon one can trace a line to the Centennial celebrations—during which Washington’s breeches were displayed in a room of presidential relics—and to the colonial revival that flourished into the twentieth century. In his Daughters of Revolution (fig. 2), Grant Wood made an emblematic statement about the colonial revival appropriation of George Washington. On the living room wall, behind the female descendants of the Revolution gathered for tea, Wood included a print of Washington Crossing the Delaware. Leutze’s famous painting appears here in both of its twentieth-century incarnations: quaint and antiquated as well as infinitely reproducible.18

The idea of domestication is no doubt fundamental to the cultural formation of historical memory in the United States, and George Washington is a paradigmatic case study. What strikes me as remarkable in the period under consideration here is the significance of history painting and its various subsets—historical landscape, genre, and portraiture—as a principal site of contestation. Although history painting was considered a privileged or elevated form of historical memory, it was incorporated into American life in many realms of popular culture: in the antebellum period, history paintings were presented as visual spectacles in traveling exhibitions, and they were distributed in prints and lithographs to middle-class art consumers; after the Civil War, historical scenes were reenacted in tableaux vivant and historical pageants. Under cultural pressure to be both “high” and “low,” history painting broke and collapsed during the Civil War. This book, then, studies the making and unmaking of an artistic form as well as its afterlife in post–Civil War genre and figure painting.

Chapter 1 focuses on Washington Crossing the Delaware as a representative epic history painting visible to many Americans as an original oil painting or as a print during the middle decades of the century. Tracing the painting’s history in exhibitions, criticism, commercialization, and appropriation as national icon, this chapter studies the various constituencies with a stake in history painting. It highlights the challenges for Leutze and other artists in producing large-scale history paintings for a volatile art public. Chapter 2 continues the discussion of Leutze’s epic program and its reception in the United States through an examination of a painting that introduced Spanish colonial history into North American art. Leutze’s Storming of the Teocalli by Cortez and His Troops presented a historical event from the Spanish Conquest of Mexico. The work’s exhibition in the galleries of the American Art-Union coincided with the Mexican-American War (1846–48) and confused its audience. During the era of U.S. expansion and manifest destiny, Leutze’s painting of violent struggle between European conquerors and Aztecs suggested uncomfortable analogies. The chapter focuses on the American Art-Union, the principal antebellum art institution that supported Leutze, and on how this organization packaged historical art for a middle-class public.

Chapter 3 introduces a third example of history painting as a struggling genre. Daniel Huntington’s Republican Court (Lady Washington’s Reception Day) domesticated and feminized American history and its republican founding fathers and mothers. But the painting’s ostentatious display of republican aristocracy also brought into relief the distance between an idealized antiquarian view of the past and the realities of modern life. The story of The Republican Court highlights the difficulties history paintings had in generating support and surviving the Civil War. Chapters 4 and 5 introduce two painters who represent the shift in taste toward more domesticated forms of historical art. Eastman Johnson, who worked with Leutze in Düsseldorf, emerged as the most successful painter of the past, including the recent past, in genre works. Painted shortly after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson’s genre painting Boyhood of Lincoln eulogized the slain president. Johnson painted such an intimate view of the young Lincoln reading by the fireside that he seemed to be “at home” with his subject. The home was not necessarily the arena in which history was made, but it appeared in paintings as a sphere where history was taught, read, and discussed.

Lilly Martin Spencer, who started her career with an interest in serious historical or moral painting, moved into domestic genre painting but never abandoned historical and moralizing themes. In one of her domestic genre paintings, War Spirit at Home; or, Celebrating the Victory at Vicksburg, Spencer aligned the domestic sphere, including children, nursing mother, and domestic help, with the larger Union cause. In a seemingly banal domestic scene, she celebrated not only an important Union victory but also the historical consciousness of ordinary people. Genre paintings such as these avoided the world-historical events that Leutze saw as the essence of history. They did not show heroes “braving the ocean and an unknown wilderness,” but they quietly resonated with historical themes and spoke to their audiences in terms that were more of the present than of the past. Spencer and Johnson highlight the instability of the art market around the time of the Civil War, the erosion of the traditional artistic hierarchy, and the emergence of a new postbellum system of cultural validation.

The concluding chapter reflects on the state of historical art during the Centennial celebrations of 1876. These celebrations and exhibitions in Philadelphia bring together the cultural trends of the previous three decades and set the stage for later forms of historical memory. Grand and opulent historical works returned with a vengeance, but they now had to share the stage and compete for popularity with many other domesticated forms of art.

The transformation that I describe took place in many areas of American culture as well as in dialogue with European developments. The art historian Stephen Bann has described the romantic period in Europe, comprising at least the first half of the nineteenth century, as an age of “historical-mindedness.” He reminds us that the “cult of history,” although it took heterogeneous forms and was conditioned by specific national circumstances, spread across France, England, Germany, and the United States. What Bann calls the “desire for history” found its way into established as well as “transgressive” genres. It produced knowledge among “professional historians” and affected a “mass reading public.”19 This desire for history, I would argue, increased the demand for historical images but also put a great deal of pressure on producers to accommodate diverse audiences. While it is true that romantic historical-mindedness was a pluralistic phenomenon, a close reading of selected history and genre paintings and their reception in the United States reveals that these images were part of a struggle over cultural hierarchy.

This study is a history of the reception of historical-mindedness in the visual culture of the United States, and it draws from a variety of sources, including the material culture of exhibition and domestic display, advice literature on home decoration, personal memory, and philosophical literature. I emphasize critics and patrons, not only because they were more vocal or more conspicuous than other constituencies but because they spoke most consciously as arbiters of taste. Middle- and working-class art consumers, however, made aesthetic choices. And although these “silent” art consumers were largely absent as active critical voices in the publications I discuss, they were often present as “implied readers.”20 Both elite and middle-class audiences shared a “desire” for historical images, but their artistic preferences were contradictory and inconsistent. The relocation of historical themes from history painting into genre painting that I describe represented a shift in taste and in historical subjectivity, the individual ability to see oneself in history. The emergence of this subjectivity was not inevitable; it was part of the process that I call the domestication of history. A brief overview of some cultural and philosophical trends that brought about this domestication will place the concept in a wider historical context and establish a theoretical framework for the discussion.

In a very literal sense, the domestication of history implies a downsizing or shrinking of history painting as a monumental form. Grant Wood’s painting, for instance, illustrates the diminished size and status of Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware once it hung as a reproduction in the twentieth-century colonial revival home. Decorating the living room set up for afternoon tea, the monumental painting is stripped of its sublime luster. The downsizing of historical art, though, had already occurred during Leutze’s time. In The American Woman’s Home (1869), the arbiters of middle-class taste Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe covered just about everything the thrifty housewife needed to know about home decoration and household economy. When it came to choosing edifying and affordable art for the home, they suggested chromolithographs of genre and landscape paintings by Miss Oakley, Eastman Johnson, and Albert Bierstadt. In addition to chromos, which they praised for their color, the Beechers advised their readers to get engravings of the “celebrated pictures of the world.” Engravings as well as statuettes would give “elegant finish to the rooms,” and as “reminders of history and art” they would inspire “intelligent inquiry about the scenes, the places, the incidents represented.” I imagine the Beechers would have endorsed the reproduction of historical works for instructional use, but when it came to the question of their personal taste, they opted for Bierstadt’s landscape, the only work mentioned twice in one chapter.21

The shrinking of history paintings could easily lead to their vanishing. The novelist and art critic Henry James described a metaphorical vanishing of sorts when he reflected on his experience of seeing Washington Crossing the Delaware as a child and then revisiting it as an adult. Writing in 1913, James remembered Leutze’s “epoch-making masterpiece” under the “wondrous flare of projected gaslight” when it was exhibited at the Stuyvesant Institute in New York in 1851. Everything about that evening thrilled James. The painting’s exhibition was a dramatic event that years later still provoked a “swarm of associations” in James. The painting had inscribed itself on his memory with an onslaught of “accessories” that made him “responsive to every item.” What captured his imagination was “the profiled hero’s purpose . . . of standing up, as much as possible, even indeed of doing it almost on one leg, in such difficulties, and successfully balancing.” Yet James’s later encounter with the work was a painful reminder of the “cold cruelty with which time may turn and devour its children.” Childish wonder was displaced by adult disillusionment: “The picture, more or less entombed in its relegation, was lividly dead—and that was bad enough. But half the substance of one’s youth seemed buried with it.” Without giving James’s autobiographical writing too much weight, his observations are a reminder of an aging process that turned one of the most influential history paintings of the second half of the nineteenth century into a dead object. For James, Leutze’s work held no wonder beyond the lure of the literal, the accessories and minutiae of historical events, and the presence of the one-legged hero. Within the space of a lifetime, Leutze’s historical masterpiece had lost its credibility, and its value as a living memory had vanished.22

A second, closely related meaning of domestication is that of taming, especially in the sense of taming something wild. Washington Crossing the Delaware was awesome and sublime, and it represented history as undomesticated struggle. In visual terms it was the antithesis of the nurturing domestic comfort that Catherine and Harriet Beecher promoted for the American home. The Beechers’ writings on household economy were steeped in the cult of domesticity, a social and cultural movement of the antebellum period that elevated the status of women as nurturers and arbiters of taste in the domestic sphere. It seems that the cultural forces that tried to bring historical perceptions in line with the cult of domesticity culminated in the early 1850s. It was during this decade that the movement to preserve Mount Vernon gained momentum. According to Patricia West, Mount Vernon became the prototype for the historic house museum, and it serves as an example of how history became incorporated into “domestic religion.” Indeed, the domestic sphere was sacred ground in Victorian America. The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, under the leadership of Ann Pamela Cunningham, turned the campaign to raise funds for the purchase of Mount Vernon into a “crusade” and linked its fate with that of the Union. As one spokesman for the Mount Vernon preservation movement declared, upon completion of the purchase and necessary preservation work, Americans would make their “pilgrimage” to the home of George and Martha Washington as “grateful children.”23

In 1851, the same year that James went to see Leutze’s grand painting, Horace Bushnell, an influential minister from Connecticut, gave an address, or “secular sermon,” titled “The Age of Homespun” that laid out a formula for linking historical memory with domestic life. Addressing a gathering celebrating the Centennial in Litchfield County, Bushnell made it his task to remember the “unhistoric deeds of common life” rather than the “historic pictures” that celebrated the “name[s] of a prominent few.” Ironically anticipating the late twentieth-century historical interest in the economic and material circumstances of everyday life, Bushnell suggested that the historians of Litchfield County should look not for “the tall monuments and the titled names” but for “the kings and queens of Homespun,” among whom he ranked housewives, millers, smiths and coopers, schoolmistresses, and church deacons. The history that Bushnell had in mind “flow[ed] in silence,” unfolding at a distance from the records one associated with the word “History” (which Bushnell called a “fiction”). The history that Bushnell wanted his audience to remember was that of a “Puritan Arcadia” revolving around precapitalist modes of exchange: there was “little passing of money,” and wives were the “help meet to men”; they worked at home, not in the cotton mill. The taming of history that Bushnell’s sermon envisioned was thus a taming of “modern” history. The historical “silence” from which he encouraged his audience to draw their historical lessons stood in direct contrast to the historical noise of modernity and industrialization. In its celebration of an Arcadian state of domestic economy, the sermon shared with the Mount Vernon preservation movement nostalgic sentiments for a premodern agrarian past. Both modes of historical perception, religious sermon and house museum, were deeply indebted to values of paternalism, both the paterfamilias of the household economy and the “father” of the nation.24

In the antebellum period, women writers and feminized historical narratives increasingly supplemented and challenged the epic narrative model and its paternalistic assumptions. In her groundbreaking Feminization of American Culture, the cultural historian Ann Douglas has analyzed the split between epic histories written by male romantic historians and the historical work done by ministers and women. While the romantic historians Bancroft, Parkman, Motley, and Prescott were writing epic panoramas inspired by sweeping philosophical ideas and focused on violence and masculine exploits, ministers and women were concerned with the sentimental, local, and antiquarian aspects of history. By 1850, according to Douglas, feminized forms of historical thought had “triumphed” over masculine “monumental” history. Clerics such as Bushnell and women such as the novelist Lydia Huntley Sigourney set out to “redeem” what male historians dismissed as the waste of history, the material excluded from “imperialist Hegelian history.” Douglas traces a shift around the mid-nineteenth century from the high intellectualism of Hegelian philosophy toward a re-Christianizing and personalizing of historical thought. The literature by clerics and female authors turned toward biography, memoir, and commemoration (Bushnell’s “Homespun” sermon is a good example). Although Douglas sees this biographical turn as largely “antihistorical” and escapist, I would argue that it also represents the desire to tame the historical forces that seem to overwhelm an individual or a group. As Douglas points out in analyzing the importance of the patriarch in the “sentimental literature of the antebellum period,” especially in Sigourney’s works, that patriarch is now a benevolent “ancestor comfortably stowed away in the rocking chair, the male softened by the kindly touch.” This domesticated patriarchy thus becomes an essential instrument in the taming of history, not just as epic grand narrative but also as the record of “progress.” The feminization of history by clerics like Bushnell, elite women like Cunningham (both ultimately fixated on paternalism), and sentimental novelists and biographers suggests a larger effort to both resist and accommodate the forces of modernization.25

This leads me to a third sense in which domestication can be applied to this study, the philosophical justification. Philosophers did not abandon the problem of reconciling historical methods with the dynamic modern world. In Ralph Waldo Emerson’s various writings, history is something organic and lived, not abstract and extraneous to human experience. According to the literary historian Russ Castronovo, Emerson sought to reconcile “monumental culture” with “democratic principles.” Thus Emerson’s claim in his essay “History” that “there is properly no history, only biography.”26 The Emersonian belief in self-reliance (the self as the source of heroism) laid the conceptual foundation for an antimonumental history.

In his essay “Art,” Emerson gives a strong philosophical endorsement of the domestication (although not the feminization) of history. Toward the middle of the essay Emerson writes, “I now require this of all pictures, that they domesticate me, not that they dazzle me.” Yet what appears to be a straightforward demand turns out upon closer examination to be an enigmatic statement. I believe that one can tease out the complex meaning of Emerson’s use of the word “domesticate” from the larger context of the essay. Emerson works from the premise that art and nature move organically and progressively toward new creation, and that both are equally part of one spiritual reality. There is some value in studying older art forms, but only “as history” (Emerson lists, for example, “Egyptian hieroglyphics” and “Indian, Chinese, and Mexican idols”). Venuses and Cupids might have been appropriate symbols for the artists of antiquity in expressing their “passion for form,” but they cannot serve the same purpose for the modern artist. Because art and nature revolve around the same philosophical axis (which Emerson calls both “Inevitable” and “Necessity”), objects in nature and objects of artistic creation are of equal merit: “A good ballad draws my ear and heart whilst I listen, as much as an epic has done before. A dog, drawn by a master, or a litter of pigs, satisfies, and is a reality not less than the frescoes of Angelo.” In Emerson’s conception of artistic “progress,” historic art (masterpieces of the past) stands in the way of the realization of the “Genius of the Hour.” The spirit can manifest itself only in new forms, not in the formulaic. Take Emerson’s example of sculpture: “But the statue will look cold and false before that new activity which needs to roll through all things, and is impatient of counterfeits, and things not alive.” Emerson here echoes James’s sense of disillusionment when he revisited Washington Crossing the Delaware. Like Emerson’s statue, Leutze’s masterpiece had become an inanimate object. Both men share a sense of aversion to the monument, the seemingly immortal work that in reality is dead and cold. Or perhaps one should speak of Emerson’s attitude toward monuments as indifference rather than aversion. Leading up to the passage on “domesticating” art, Emerson describes an encounter with European masterpieces that anticipates James. Emerson describes his fantasies of the “great pictures” as schoolboyish. He expected to feel “foreign wonder” and “barbaric pearl and wonder” in Rome and Paris, yet what he found was a familiarity he thought he had left behind in Boston. “I now require this of all pictures,” he concludes, “that they domesticate me, not that they dazzle me. Pictures must not be too picturesque. Nothing astonishes men so much as common-sense and plain dealing. All great actions have been simple, and all great pictures are.” The use of the word “domesticate” here is complex. Emerson identifies the domestic with what is familiar and common, but it is also a principle that clarifies art rather than obfuscates, makes art comprehensible rather than mysterious or arcane. The domestic, for Emerson, is the principle that animates art.27

A second philosophical apologia for domesticated art can be found in the writings and lectures of the continental philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, who is credited with inspiring such American epic historians as George Bancroft and William Prescott. In his multivolume Philosophy of Fine Art, Hegel formulated a justification for an art of the simple life, or what he called “prosaic objectivity” or the “content of everyday life.” In a section preceding a discussion of Dutch genre art, he asserts that the realm of poetry is “ordinary domestic life—the main source, that is, of the probity, commonsense spirit, and the morality of everyday life—which is presented by art in the usual developments of civic life, in scenes and characters selected from the middle and lower classes.” Elaborating on the content of such “prosaic” art, Hegel lists “contingent phenomena of reality” such as man’s “accidental habits . . . attitudes, activities of family life, his business as a citizen,” and the “shifts and changes in the world around us.” Echoing Emerson’s demand that “the artist must employ the symbols in use in his day and nation,” Hegel envisions an artist or poet who draws from “the national life . . . and his immediate public.” Emerson and Hegel were both striving toward an aesthetics in which art became identical with spirit or soul. Both found their aesthetics realized in art that stayed close to the material reality of domestic life. While Emerson thought of symbolic language as a necessary step in the realization of the spiritual in art, Hegel’s concept of the spirit in art relied on immanent presence, a result of the artist’s attempt to re-create “naked reality,” or what came “immediately before the vision.” The art form in which Hegel found this immanent presence most fully developed was Dutch genre painting.28

A survey of the different cultural and philosophical forces that called for domesticated art forms would suggest that the decline of history painting, especially in its most epic and monumental manifestations, was inevitable. History painting, one might assume, simply stood in the way of the social and cultural push toward democratization, feminization, secular spirituality, in a word, modernization. As Raymond Williams has argued, the ideology of modernism implies the inevitability of its own dominance over traditional culture. Modernism repudiated “fixed forms” and “settled cultural authority,” and it culminated in the late nineteenth century, when an explosion of media transformed cultural production forever. There is much truth to the assumption that history painting could not survive modernism. The practice of history painting certainly declined around the time of the Civil War, although it bounced back at the Centennial and on other occasions when the painting of grand themes appealed to the opulent tastes of the art public. But simply assuming the obsolescence, and the death, of history painting is to gloss over the cultural conflict that its demise entailed.29

Writing from the perspective of the twentieth-century art philosopher, Theodor W. Adorno developed a persuasive genre theory that, I believe, applies to history painting. Although genres and artistic conventions function as universal rules, they rarely reach a state of pure realization in artworks. An artifact can only provisionally and incompletely wear the fetters imposed by a genre. In working through a genre, be it in music, literature, or visual arts, artists also subvert it and contribute to its erosion. Genres, Adorno states somewhat polemically, are “artificial or conventional to begin with”; they are born “dead.” Over time, “conventional genres are like after-images of authority” that “art cannot take . . . seriously.” But even when genres become comical or “hilarious,” because no one takes them seriously anymore, they are still universally understood and “at the beck and call of society.”30

Adorno’s rather abstract theories on the “death” of genres help account for a central problem in making sense of the changing status of history painting around the middle of the nineteenth century. History painting was simultaneously a source of authority and an object of ridicule. The more forcefully its detractors wanted it dead, the more resiliently it clung to life. The seemingly inevitable “death” of history painting turns out to be a fierce social and cultural struggle over its legacy. Adorno’s approach would also explain why history painting is still considered an issue in the interpretation of Rockwell’s art and why it may continue to surface in the future. The links between twentieth-century pictures of history and nineteenth-century precursors in both history and genre painting are numerous. To begin this book with Emanuel Leutze is to confront history painting in all its nineteenth-century contradictions, as an art form that was forceful and dominant but at the same time struggling and weak.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.