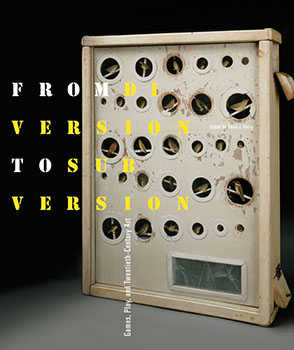

From Diversion to Subversion

Games, Play, and Twentieth-Century Art

Edited by David J. Getsy

“Far too often the seriousness of high art has been invoked at the expense of compelling art’s sheer gratuitousness, irrepressible impertinence, and spontaneous playfulness. A welcome and particularly bracing overturning of this staid approach is David J. Getsy’s From Diversion to Subversion, a collection of lucid essays by established and emerging scholars, which focuses insightfully on the oxymoronic turns of serious humor, games played in earnest, and ludic research.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Aside from the editor, the contributors are Florencia Bazzano-Nelson, Jon Cates, Mary Ann Caws, Susan Laxton, Claudia Mesch, Kevin Moore, Gavin Parkinson, Anne-Marie Schleiner, Owen F. Smith, Ellen Handler Spitz, Stephanie L. Taylor, and Debra Wacks.

“Far too often the seriousness of high art has been invoked at the expense of compelling art’s sheer gratuitousness, irrepressible impertinence, and spontaneous playfulness. A welcome and particularly bracing overturning of this staid approach is David J. Getsy’s From Diversion to Subversion, a collection of lucid essays by established and emerging scholars, which focuses insightfully on the oxymoronic turns of serious humor, games played in earnest, and ludic research.”

“Getsy’s anthology is a strong piece of work, with older theories of play marshaled not to justify the fun house that the art world has become in our day, but to remind us of how deeply modernists have engaged with a range of ludic possibilities.”

David J. Getsy is Goldabelle McComb Finn Distinguished Chair in Art History and Associate Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction

David J. Getsy

Part I: Games and Play in Twentieth-Century Art History

From Judgment to Process: The Modern Ludic Field

Susan Laxton

The Duchamp Code

Gavin Parkinson

My Utopia: Play in Bauhaus Photography

Kevin Moore

Serious Play: Games and Early Twentieth-Century Modernism

Claudia Mesch

Surrealist Gaming: Rules and the Rest

Mary Ann Caws

Playing in the Sand with Picasso: Relief Sculpture as Game in the Summer of 1930

David J. Getsy

Joseph Cornell’s Dangerous Games

Stephanie L. Taylor

Playing with Dada: Hannah Wilke’s Irreverent Artistic Discourse with Duchamp

Debra Wacks

Dick Higgins, Fluxus, and Infinite Play: An “Amodernist” Worldview

Owen F. Smith

1Subversive Toys: The Art of Liliana Porter

Florencia Bazzano-Nelson

Part II: Contemporary Artists’ Views on Play and Games in New Media and Public Practices

Dissolving the Magic Circle of Play: Lessons from Situationist Gaming

Anne-Marie Schleiner

Running and Gunning in the Gallery: Art Mods, Art Institutions, and the Artists Who Destroy Them

Jon Cates

Coda: Distinguishing Art from Play

Zigzagging with Full Stops from Play to Art

Ellen Handler Spitz

List of Contributors

Index

Introduction

David J. Getsy

The story of art in the twentieth century has often been told as one of sustained, serious research. Commentators and advocates of modern art have likened its rapid changes and successive innovations to the scientific method and its testing of hypotheses. The analogy to the hard sciences is not accidental, and this rhetorical move aimed to justify modern and contemporary art as a specialized discipline, building evermore upon its own gains. Such narratives of art as research nevertheless rely upon multiple exclusions and scotomata. While there no doubt have been artists who understood their practice as informed by something like the scientific method, there are many more who have willfully pursued less punctilious ways of making art. An often-quoted statement by Pablo Picasso makes just such a case: “I can hardly understand the importance given to the word research in connection with modern painting. In my opinion to search means nothing in painting. To find, is the thing. . . . Among the several sins that I have been accused of committing, none is more false than the one that I have, as the principal objective in my work, the spirit of research. When I paint, my object is to show what I have found and not what I am looking for.” Underneath the brashness of Picasso’s sweeping comments is a resistance to just such a goal-driven and teleological way of thinking as that which emerged in the narratives of the history of modern art (many of which continue to give Picasso himself a starring role). For Picasso, “research” assumed that one knew what one was looking for and was merely finding the way to get there appropriately—that is, a predetermined hypothesis to be proven valid or invalid. By contrast, Picasso emphasized nondirectedness, chance, and exploration as ways of proceeding.

This collection of essays takes up these very themes in twentieth-century art history: the nonserious, the playful, and the exploratory. It will do this through a focus on games and play, both of which are often sidelined in the narratives of modern art as earnest research. By contrast, the essays in this volume take seriously the supposed non-seriousness of games and play, showing how they contribute to and complicate the narratives of modern art and how they served as sites of creativity and criticality. Games are, at base, representational activities, and artists and critics saw the game as an analogue to art practice, a metaphor for creativity, or a model for art criticism. This collection does not aim to be a comprehensive survey of the many and varied instances in which artists and critics explored games and ludic activities. Rather, it brings together a group of studies of key moments in the history of twentieth-century art as a means of indicating the diversity of issues at play in play. Similarly, the essays have not been organized around singular definitions of either games or play. Rather, their deployments of often divergent ways of characterizing these terms are indicative of the diversity of frameworks for dealing with the ludic, as I discuss below. Collectively, however, the essays in this volume point to the complexity of games and of play, demonstrating some of their central and recurring uses for art in the twentieth century.

The impetus for this collection derived from the burgeoning field of Game Studies, itself fueled by the recent expansion of video, computer, and online games as focal points in contemporary culture. With the growth of the mainstream video-game industry and the simultaneous proliferation of alternate practices that deploy the tactics and technologies of video games for cultural critique or activism, games have emerged as a major topic for scholarly inquiry. The examination of games is of course not itself new, and it has been a long-running site of inquiry for such fields as philosophy, mathematics, psychology, and anthropology. However, when the video-game industry began to outpace the major motion picture industry in revenue and production values, the scholarly foundations of Game Studies in these disciplines were remined and reinvigorated. Drawing on the burgeoning literature and methodology that seeks to analyze these developments, the essays discuss the ways in which artists imposed rules of play on their work or sought out games or play as possible means to refine or complicate art theories and practices.

Games are notoriously difficult to define, and much of the literature has focused on questions of taxonomy. This is the case with the foundational text in Game Studies, Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens (1938), and its primary interlocutory text, Roger Caillois’s Man, Play, and Games (1958). It has become conventional in the literature of Game Studies to rehearse and to refine the ways in which one recognizes and categorizes games, usually with reference to these two texts which are cited as authoritative justifications for the attention to games or play in the first place. Claudia Mesch’s essay in this volume provides a thorough critical overview of the positions of Huizinga and Caillois, discussing in particular the important affinities with Surrealist art practices. In contrast to the historical specificity of Mesch’s essay, these two foundational texts and their taxonomies have often been uncritically excerpted and appropriated without reference to the historiographic and (as Mesch urges) political situations of their authors. Accordingly, in this introduction, I will not yet again restate Huizinga’s or Caillois’s well-worn categories, though their terms are registered at different points in this volume. I demur out of a belief that the taxonomic urge that has underwritten the development of the field of Game Studies often distracts attention from the actual deployment of games and inadvertently shuts down their complexity and polyvalence. That is, the task of taxonomy in many respects is bound to fail with regard to a topic like games, which mutate and morph depending on who plays them, when they are played, where they are played, and why they are played.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, who famously used games as a core concept, proposed a different way forward. However, he argued that there was no essential or single definition of games possible. He wrote: And we can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way; we can see how similarities crop up and disappear. And the result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities. I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than “family resemblances”; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, et. etc. overlap and cries-cross in the same way.—And I shall say: “games” form a family. Wittgenstein’s concept of “family resemblances” moves beyond the search for an essential definition, pointing to the ways that a definition of a group can be recognized even when there is no single trait shared by all its parts as long as there is a degree of shared traits with others in the same group. This is useful not only in the study of games but also as a warning about relying on stable taxonomies, themselves purporting to be created through scientific methods but, ultimately, relying on subjective distinctions.

A commonly held concept across the divergent accounts of games and their family resemblances, however, is that games are such important cultural and developmental activities because they provide a surrogate arena for interactivity and absorption. Play occurs in the alternate zone established through the parameters of the game, and players identify with and project themselves into this game space, regardless of the degree of verisimilitude of the game or the formality of the rules that make it up. This also holds true in spontaneous, free play outside of traditional games, and Huizinga identifies the play element in multiple facets of human existence. His major contribution was to argue that the centrality of games and play to cultural life derived from the “temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart” created through them. Being “caught up” in a game is the result of the players’ psychological immersion in that temporary world apart and of their resultant fueling of identification with its constituents. From a game of chess, to a soccer match, to less formal (but no less engaging) games that sometimes emerge in social interactions (office politics, public flirtation, and so on), participants’ heightened engagement becomes possible because of this bracketing within the normal and the everyday of an alternate time and space of game/play in which they can and do act and identify differently and more intensely.

“Play” refers to the participants’ immersion in this temporary world, be it a formal game with explicit rules or moments of virtual behavior in the mundane. In this sense, play is a more expansive category—an activity that can interrupt conventional ways of acting. Play can occur spontaneously and outside of clearly defined games. Nonce games, ad hoc contests or collaborations, and performances of virtuality (the “what if?” moment of pretending) are all forms of play that erupt into the everyday. Such ludic behavior is enabled by the ostensible nonseriousness that is bracketed off from the exigencies of the mundane. One is “just playing” when one’s activities do not resemble what one would or should normally do. As with games, this is not to say that play does not have real outcomes and repercussions into the mundane. Quite the contrary, play activities such as flirtation, mock fighting, imitation, or parody can at times fundamentally reorder the social relations that they are supposedly apart from. Furthermore, play and games can also provide critical reflection on actual events and situations. It is this potential that has made play a central tool in the critical aims of performance art, for instance. Play’s capacity for diversion from the everyday—both in the sense of a light distraction from the mundane as well as a skewed push away from it—also enables its potential for subversion and critique. Accordingly, the liminality of play and its potential for acting and being otherwise, if even temporarily, has made it a powerful metaphor for artistic creation and for the aesthetic encounter. In the first chapter, Susan Laxton provides an overview of play’s importance in aesthetics and in conceptions of the avant-garde, and this is a theme that is tracked throughout the book.

Much attention has been given to the importance of play as the foundational creative activity in early child development, and many of the studies of play and games have followed Huizinga in positing play as a central aspect of human relations. The work of Brian Sutton-Smith, in particular, has been central in anthropological and developmental studies of the cultural relevance of play and games. From many quarters, play has been taken up as a core metaphor for the complexity of cultural production. Perhaps the most useful and long-running discussion of the importance of play has been that of the British Object Relations psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott. Building upon the important work of Melanie Klein’s focus on children and her development of the “play technique,” Winnicott developed an extensive analysis of the importance of play as a means to understand not just children’s experience but also that of adulthood. For Winnicott, play was important because it afforded the opportunity to break down the distinction between self and world for a time. He based his ideas on a revised account of early childhood development, shifting emphasis from Freud’s focus on the Oedipal to the development of subject-object relations more generally. The infant, he believed, underwent a process in which the self was differentiated from the world, allowing the slow process of recognizing other subjects. He used the term “transitional space” (sometimes “potential space” with reference to adults) to discuss the position of the infant who still has a porous relation between self and world, between the awareness of itself as a subject in a field of objects and other subjects.

This is significant for play and, Winnicott would go on to argue, cultural and aesthetic experience more generally because it was the position of this “potential space” that the playing child or adult temporarily reinhabited. Children’s ability to remake everyday objects into tools of their imagination assumes a lack of distinction between subjective intentionality and the objective environment. In the most direct terms, the cardboard box becomes the spaceship, and so on. For adults, Winnicott argued that it was in the experience of creativity and in the aesthetic encounter through which the “potential space” could be temporarily reaccessed. He used as his example being immersed in the experience of listening to music. The listener will identify with a piece of music and feel that it is somehow speaking to her or his experience, causing a range of emotional and affective responses. Similarly, this example could also be extended to the engagement people feel when watching a movie, looking at a painting, being a spectator at a sports event, or playing a video game. Winnicott’s account of play is useful because it offers a description of how and why some artworks are effective on some and not others, how the experience of game-play is meaningful and potentially liberating (think of the massive online communities of adults playing World of Warcraft), and why play is a recurring component of social relations and adult life. Furthermore, Winnicott’s account privileges artistic creativity as an example of the repositioning of “potential space,” drawing an analogy between the child’s play and the artist’s creation of new images and ideas. As Ellen Handler Spitz argues in her chapter, the equation between child’s play and adult art is often overstated. Nevertheless, Winnicott’s expanded definition of play and its relation to creativity are useful in thinking about how games can offer both diversion and subversion.

I focus on Winnicott’s account of play because of the importance that art and creativity have within it. For Winnicott, the creative act gains not only its individual importance but also its wider relevance for a community through the refusal to accept a gulf between self and world, between subject and object, and between imagination and the particulars of one’s objective environment. One need not take on Object Relations Psychoanalysis in its entirety to recognize that this transformative potential and its ability to suspend how we know the world—if even for a time—gives play in its myriad forms its recurring potency. One could see the intellectual roots of such connections in Friedrich Schiller’s play-drive, which Laxton discusses in her essay. From different perspectives, this is also the lesson of Huizinga, of Caillois, of Wittgenstein, and of Sutton-Smith: that play offers the capacity to skew the conventional, to treat the commonplace otherwise, and to offer a temporary site from which to revisualize our ways of relating. Games focus and enable play. Their restrictions in the form of rules do limit actions, but in so doing they offer the parameters for creative adaptation and problem-solving. Both games and play became such rich sites of inquiry for artists and critics in the twentieth century because of these abilities to use supposed non-seriousness to view the everyday differently. They incorporated the game as an artistic tool and looked to play as a different model of making and encountering art.

This anthology brings together discussions of some of these moments. It demonstrates how an expansive definition of play allows us to reconsider the history of modern art and shows how games have had a significant presence within it. Games and play, in other words, are not inconsequential or silly. Rather, they offer the suspension of the quotidian as a means of thinking it otherwise. This open-ended exploration is at the core of many modern artists’ practice, but it has been inadequately recognized. This book takes the stand that the emergence of the field of Game Studies and its development of methodologies attuned to games, rules, and play allow us to better recognize and discuss the many ludic components that have constituted a fundamental theme in art of the twentieth century. That is, the recent developments of Game Studies can be used productively to discuss the importance of games and play in earlier historical moments. From this perspective, Picasso’s playfulness, Surrealist games, Duchamp’s affinity for chess, and so on, seem less like disconnected threads and more like different ways of addressing the potential of the ludic as artistic practice.

The selection of essays was based upon papers given at the 2006 College Art Association conference with a few additions. The initial idea for this volume came with the overwhelming response to the call for papers from a wide variety of perspectives and historical moments. It was then that I realized that there had already been a greater investigation of games in art history, and the attendance at the resulting two-panel session confirmed that. As one might expect, a central theme was the surrealist group and its contemporaries, and they have a strong presence here. Beyond that, however, I have attempted to bring in perspectives that use an expanded definition of play in the later twentieth century, focusing on the divergent manifestations this concept can have. Adding to that, the volume also includes essays by two new media artists, Jon Cates and Anne-Marie Schleiner, who assess the historical field to which they have contributed.

Susan Laxton begins the volume with an extensive discussion of the historical sources for discussing play in early twentieth-century thought, showing how it was inextricably linked to aesthetics. Examining Kant, Schiller, Nietzsche, Freud, and Simmel, Laxton charts an intellectual trajectory from the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries that placed play at the core of debates about art and its evaluation.

Gavin Parkinson uses play as a method to present a challenge to the prevalent interpretations of Marcel Duchamp. Fittingly, this methodological tool unhinges the overly deterministic accounts of Duchamp’s body of work and intentions, which seek to find a secret and consistent code through which to explain his divergent actions and works. Duchamp’s propositions often have at their core an indeterminate or unknown element that is never revealed nor given secure meaning, and Parkinson himself offers an analogous way of looking at Duchamp. Playfully, Parkinson himself embeds in his chapter such a cryptic element with no interpretative key, saying something at a crucial moment but not in any recoverable or legible way for the reader. Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s use of play and on the game-playing that underwrites Duchamp’s oeuvre, Parkinson offers a methodological intervention and prompts us to attend to the play of meaning in the work not as a problem to be resolved but as an end in itself. Resisting the classic detective-story mode in which Duchamp’s work has been persistently cast, Parkinson instead deploys this method to avoid those interpretations that consistently attempt to put a halt to Duchamp’s play.

Moving from the use of play as methodology to its historical role in 1920s in the Bauhaus, Kevin Moore shows how the practice of photography offered an alternative and at times critical way of engaging with the Bauhaus’s emphasis on rationalism in design. Play, he argues, manifested itself in the photographic work of professors and students, who explored photography as a subversion of the technological utopia propounded by the Bauhaus. Attending both to the photographs and to their pedagogical context within the Bauhaus, Moore demonstrates how the ostensible purity it aspired to could be subverted through photographic practice. Ultimately, it was photography’s liminal role in the curriculum of the Bauhaus that allowed those who used to it explore the ludic and its critical possibilities.

This volume reprints Claudia Mesch’s 2005 article on games and early twentieth-century art. Her chapter provides a thorough discussion not just of Huizinga and Caillois but also of the importance of games and play for the Surrealists and for Duchamp. She positions these authors and artists in relation to their historiographic and political contexts, demonstrating the ways in which play was an axis of engagement. In particular, Mesch foregrounds the roles of competition and of collaboration as motivating and enabling factors, arguing that such an approach offers a key to understanding the divergent approaches to games developed by Duchamp and the Surrealists. As such, it offers an important analysis of the historiographic positioning of the foundational texts for Game Studies and for the artists whom we most immediately identify with games in art.

Mary Ann Caws, the distinguished scholar of Surrealism, provides an exploratory and at times personal reflection on the importance of games and chance in Surrealism, gesturing to the ways in which the specific framing of games provided the impetus to reconsider the given world differently. As she contends, the Surrealists saw the freedom of chance as opening the freedom of one’s imagination. She discusses how the Surrealist emphasis on the restrictions of rules and of the demands of collective behavior each allowed the possibility of individual personalities to emerge in response. In short, the constraints of the rules provide the opportunity to relate to the world differently. In this way, we can understand the importance of games and their limitations to the Surrealist project.

In my contribution to this volume, I discuss an often-overlooked group of works made by Picasso over the span of two weeks in the summer of 1930. These “sand reliefs,” as they are called, engaged with the medium of relief sculpture and used its parameters as rules of a game Picasso played. Across the eight works that make up this set, Picasso toyed with questions of two- and three-dimensional imaging. In particular, I focus on the role of the shadow as a central component of relief sculpture and Picasso’s allegorizing of it through the introduction of a silhouette in the early reliefs. By discussing the importance of the silhouette for Picasso in these years, I show how an undirected process of play around it and in the framework provided by relief sculpture generated new ways of thinking about sculpture. Throughout, I attend to the open-endedness of Picasso’s play and the back-and-forth testing of rules in the sand reliefs in order to demonstrate how the perspective of Game Studies can bring to light new ways of considering artworks and the artistic process.

In her chapter on Joseph Cornell, Stephanie Taylor draws out the ways in which games and their ostensible nonseriousness often mask deeper and more complex issues. In particular, she shows how Cornell’s works can be productively placed within the context of Surrealism’s emphasis on sexuality, revealing the very adult concerns beneath the seemingly innocent boxes and assemblages. Taylor examines Cornell’s recurring interest in childhood but points to his engagement not just with its idyllic representations but also with its perils. Similarly, she examines his toylike boxes in relation to his obsessions with certain woman, characterizing the works as manifesting his conflicted attitudes toward them. She concludes that play is a central arena of investigation for Cornell, both in his foregrounding of it in his works and their interactivity and in his self-presentation. He used play in both these ways, she argues, to divert the viewer from the disturbing and often deeply personal stories his works told.

In her analysis of Hannah Wilke’s use of humor, Debra Wacks looks at the various games Wilke developed and the parodic play through which her work engaged with the reputation of Marcel Duchamp. Through a series of works, Wilke responded to Duchamp’s works, using his own preference for wordplay as a tool to subversively mimic his strategies. In particular, Wacks examines Wilke’s performances and films that engage with Duchamp in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, showing how the films themselves became games of extended quotation and parody with multiple references to Duchamp’s work.

Owen Smith contributes a polemical account of what he calls “amodernism,” a term that he uses to describe the destabilizing and open-ended tactics of Dada and Fluxus, in particular. Focusing on the writings of Dick Higgins, Smith discusses the concept of “infinite play” and its usefulness as an interpretative lens to bring out the aims of the Fluxus group and the transformative potential of its tactics. Countering the frequent assumption that Fluxus game-playing is simply unserious, Smith makes a case for their play as a reconsideration of the boundaries between art and life and between artist and viewer. In short, he argues that play functioned as a crucial critical mode for Higgins and for Fluxus.

Florencia Bazzano-Nelson examines the use of toys and play in the artwork of Liliana Porter from the 1960s to her more recent work in film. Showing how the toy can operate to open up possible meanings and to allude to unplayful content, Bazzano-Nelson makes the case that Porter’s work has been deeply involved with the use of play as a tactic of subversion.

The next section brings together assessments of recent art practice by two new media artist-critics, Anne-Marie Schleiner and Jon Cates. Schleiner draws upon Situationism as a precedent for new modes of facilitating participation in recent new media art. With an emphasis on public practice, she holds that certain lessons taken from Situationist writings are useful in thinking through current uses of new media to relate to social spaces. Jon Cates outlines the history of video-game modification as art and examines how technologies from mainstream media and popular culture were adapted and exploited by artists to critical ends. He focuses on artworks that modify first-person-shooter games to represent and engage with the museum or gallery space in which they are exhibited. By allowing for an interaction with the space of the art institution, these works offer a new way of considering the role of video games within exhibition contexts. These works have the potential to appropriate and to engage critically with not just these spaces but also with the other works that they take as their targets.

In a fitting close to the volume, Ellen Handler Spitz discusses the frequent elisions between child’s play and art. While noting some of the similarities, she argues that both lose when being simplistically equated with the other. She discusses how certain modes of play from childhood are taken up by modern and contemporary artists and draws points of comparison and contrast with children’s use of games and toys. In so doing, she maintains the importance of distinguishing between the different personal and public uses of child’s art versus that of the contemporary artist, clarifying the need to attend to play in art as a multifaceted and complex topic.

These essays do not settle on a stable history of games or play in twentieth-century art. Games and play themselves resist such easy taxonomies and positivistic accounts. Instead, they exhibit a family resemblance in their investigations of the ludic. Cumulatively, they themselves play with the ineradicable and undeniable presence of modes of gaming and of play as method in our ways of thinking about modern and contemporary art. The conjunction of the capacity for diversion and the potential for subversion links all of these investigations and helps to indicate just some of the ways in which games and play have served such a catalytic function for artists and critics in the twentieth century and beyond.

© 2011 Penn State University

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.