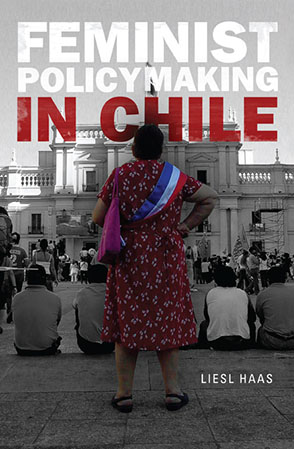

Feminist Policymaking in Chile

Liesl Haas

“Haas persuasively argues that feminist policymaking can be explained as a process of political learning in which Chilean women's rights activists engaged over time. Surprising changes in policy toward abortion, domestic violence, and reproductive rights occurred as movement strategies, action within the parties, and legislative activity evolved over time. Haas is uniquely positioned to analyze the feminist movement in Chile because her research covers more than ten years of observations about feminist politics. This is a real strength that other books lack. Taking the long view allows her to show how activists learned to navigate the newly democratic political terrain. I find this a compelling way to think about change in the Chilean case and an apt way to explain policy outcomes in other countries as well.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

“Haas persuasively argues that feminist policymaking can be explained as a process of political learning in which Chilean women's rights activists engaged over time. Surprising changes in policy toward abortion, domestic violence, and reproductive rights occurred as movement strategies, action within the parties, and legislative activity evolved over time. Haas is uniquely positioned to analyze the feminist movement in Chile because her research covers more than ten years of observations about feminist politics. This is a real strength that other books lack. Taking the long view allows her to show how activists learned to navigate the newly democratic political terrain. I find this a compelling way to think about change in the Chilean case and an apt way to explain policy outcomes in other countries as well.”

“Feminist Policymaking in Chile breaks new ground in research on gender politics in Chile by providing a fascinating account of the variables that help or hinder the passage of women’s legislation. This expertly researched and executed study provides a sophisticated treatment of political learning and presents the interesting case that a women’s executive agency may actually work at cross-purposes with feminists’ legislative goals. This book is required reading for those seeking to understand the political status of women in Chile.”

“This careful and empirically rich analysis is a hugely valuable contribution to the study of feminist policymaking, not only in Latin America, but more broadly.”

“Leisl Haas’s book is a welcome contribution to the study of feminist policymaking, and one that brings Latin America to the forefront of this field. Based on extensive interviews and archival work, Haas provides an insightful and engaged analysis of the politics of feminist-inspired legislation on divorce, abortion, and violence against women in Chile. Through her narratives of the legislative process, Haas exhibits an especially acute analysis of the institutional factors that serve to either stymie or advance feminist legislative efforts. Yet, as she makes evident in her case studies, while institutions are critical factors, there is also much room for strategy and politics on any given legislative issue. Haas’s study also demonstrates the crucial role of Left parties in advancing feminist agendas. This book will be of interest not only to those engaged in Chilean politics, but also to those more broadly interested in gender and politics, political institutions, and the contemporary importance of Left political parties in the region.”

“This is an exemplary study of Chilean legislative activity. Haas has taken a number of feminist issues—sexual abuse, abortion, and divorce—and tracked them as they worked their way through the Chilean Parliament. . . . Haas follows this all very closely with sharp insights, tallying each representative’s position with follow-up interviews. The result is a revealing portrait of Chile’s evolving transitional (1990–2008) government, climaxing with the election of Socialist Michelle Bachelet.”

“[Feminist Policymaking in Chile] is a bracing corrective for a tendency to treat political institutions and the opportunity structures that they produce as static and removed from a larger, more dynamic political context. Haas's work convincingly shows how feminist actors located in the executive branch, in the Congress, and in civil society progressively learned to overcome obstacles and create new institutional possibilities in order to promote their legislative goals. Drawing on extensive interviews with many of the most-important feminist activists in all three arenas, Haas reveals how feminist activists learned from early failures and setbacks and how this learning process helped to ensure the later passage of a number of pieces of controversial legislation, including the strengthening of the laws against domestic violence and the legalization of divorce in 2004. . . . Haas's empirically rich work provides a nuanced understanding of Chilean political processes. More broadly, Haas convincingly shows that analysis of policymaking must pay attention to how political actors learn from policy successes and failure and how these lessons become embedded within the overall process. Her engaging analysis is a must-read for scholars working on public policy and would work well in classes on women in politics, gender and politics, comparative public policy, and comparative politics.”

Liesl Haas is Associate Professor of Political Science at California State University, Long Beach.

Preface

This project began almost twenty years ago. After graduating from college I spent two years as a community organizer in rural Chile, working with women’s cooperatives in relatively isolated communities near Los Andes, north of Santiago. It’s hard to remember now what I imagined the experience would be like, but as anyone who has done volunteer work can attest, the reality is almost always more challenging, more humbling, and ultimately more transformative than one expects. My two strongest memories from that time are of being overwhelmed by the generosity of my Chilean neighbors and of being taken aback by the political engagement and sophistication of people living such a rural existence.

I arrived in Pocuro at the end of 1990, shortly after the transition to democracy. The silos and fences around my house were still covered with graffiti from the 1988 plebiscite on General Pinochet’s regime. Despite their isolation, the people in the village where I lived suffered significantly under the military government, particularly in the first years after the 1973 coup. Many of my neighbors had relatives who had been exiled abroad, or had spent time in prison, or had been tortured. Finally free to speak openly about their experiences, they poured out stories of the chaos of the Allende years and of the brutal repression that followed the coup.

I was initially shocked by the harsh conditions in which these women lived: dilapidated housing without heating, telephones, or, in many cases, indoor plumbing. Daily tasks like laundry were done by hand. Paid employment was scarce, and many men left for weeks at a time to work in mining or at the ski resorts, effectively leaving the women sole caretakers of the home and children. Yet many of the women made time to attend the cooperative meetings, where they spoke with great insight about their common struggles: of the need for better health care and birth control, of practical advice for defending themselves against domestic abuse (which was endemic in the area), of their inability to make the most basic financial decisions without the permission of their husbands, of the need for legal divorce. On multiple occasions women who by all appearances conformed to the role of traditional rural wife and mother argued passionately for the need for abortion “in extreme cases.”

These were not women who had internalized or acquiesced in the limitations of their social roles. Many could clearly articulate their inequality but felt trapped not only by a machista culture but by laws that failed to guarantee their socioeconomic and political equality. I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to these women, who first opened my eyes to the reality of women’s lives in Chile and whose tremendous hospitality and lasting friendship sustained me there and remain with me today.

In the years after my return to the United States, feminist representatives in the Chilean Congress introduced legislation to criminalize domestic violence, establish salary equity for women workers and day-care centers for their children, give married women more control over their salaries and property, and legalize divorce. Their early enthusiasm for policy reform waned, however, in the face of staunch political opposition. Sernam, the National Women’s Service, established itself as a center for policy development on women’s rights, but not without controversy—both from feminists outside the state and from political conservatives opposed to reform. The Chilean women’s movement, which had played a central role in fighting for a return to democracy, struggled to redefine its mission and its relationship with the government.

My work with the women’s cooperatives, together with the fledgling projects of the new democratic government, prompted me to consider whether, and how, women might change the inequalities that were so much a part of their lives. Could women effectively combat the cultural beliefs that limited their potential? How impenetrable were the structural factors—particularly the lack of legal protections to ensure women’s equality—that sustained and perpetuated these beliefs? This book is my attempt to investigate the extent to which women in Chile have found political strategies to challenge discriminatory laws and to create the legal framework that will improve the concrete conditions of their lives.

© 2010 Penn State University

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.