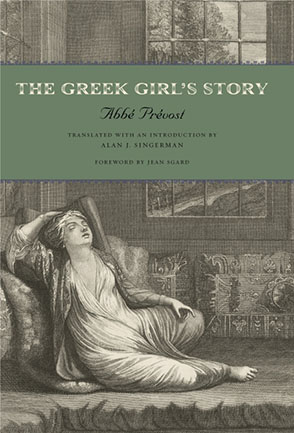

The Greek Girl's Story

Abbé Prévost, translated and with an introduction by Alan J. Singerman, Foreword by Jean Sgard

The Greek Girl's Story

Abbé Prévost, translated and with an introduction by Alan J. Singerman, Foreword by Jean Sgard

“This superb new translation by Alan J. Singerman, one of the foremost specialists on Abbé Prévost, constitutes the first scholarly edition in English of Histoire d’une Grecque moderne. This remarkable novel—an early, paradigmatic example of unreliable first-person narration, one of the greatest novels ever written on the theme of jealousy, and an outstanding example of eighteenth-century Orientalism—will appeal to a broad spectrum of readers. Singerman's introduction and notes are models of erudite scholarship and critical lucidity.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Prévost’s roman à clef is based on a true story involving the French ambassador to the Ottoman Porte from 1699 to 1711. It is narrated from the ambassador’s viewpoint and is a model of subjective, unreliable narration (long before Henry James). It is remarkably modern in its presentation of an enigmatic, ambiguous character, as the truth about the heroine can never be established with certainty. It is the story of the tormented relationship between the diplomat and a beautiful young Greek concubine, Théophé, whom he frees from a pasha’s harem. While her benefactor becomes increasingly infatuated with her and bent on becoming her lover, the Greek girl becomes obsessed with the idea of becoming a virtuous and respected woman. Viewing the ambassador as a father figure, she condemns his quasi-incestuous passion and firmly rejects his repeated seduction attempts. Unable to possess the young woman or tolerate the thought that she might grant to someone else what she has refused him, the narrator subjects her behavior to minute scrutiny in an effort to catch her in an indiscretion. His investigations are fruitless, however, and Théophé, the victim of incessant persecution, simply dies, leaving all the questions about her behavior unanswered.

“This superb new translation by Alan J. Singerman, one of the foremost specialists on Abbé Prévost, constitutes the first scholarly edition in English of Histoire d’une Grecque moderne. This remarkable novel—an early, paradigmatic example of unreliable first-person narration, one of the greatest novels ever written on the theme of jealousy, and an outstanding example of eighteenth-century Orientalism—will appeal to a broad spectrum of readers. Singerman's introduction and notes are models of erudite scholarship and critical lucidity.”

“At one time a Benedictine monk, Antoine-François Prévost (1697–1763) was a man of dubious morality fascinated by scandal and the struggle between virtue and desire. As a novelist, he wrote about enigmatic historical and fictional characters, exploring their hypocrisy, madness, and disgrace. His Histoire d’une Grecque moderne (1740), based on the actual experiences of a French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 18th century, may not be as well known as his sentimental novel Manon Lescaut (1731), but it is nevertheless a classic literary masterpiece that well deserves this outstanding new translation. . . . [This] is the first accurate, single-volume translation and critical edition of the novel. Singerman provides a fascinating introduction, extensive footnotes, and a highly reliable English rendering of Prévost’s powerful narrative, which is clearly far more than just a roman à clef. Summing up: Essential.”

Alan J. Singerman is Richardson Professor Emeritus of French at Davidson College.

Contents

Foreword by Jean Sgard

Acknowledgments

Introduction

The Greek Girl’s Story

Book One

Book Two

Appendix 1: Contemporary Source Texts for The Greek Girl’s Story

Appendix 2: Life and Works of the Abbé Prévost

Notes

Works Consulted

Introduction

The “scandalous” personal life of the abbé Prévost has long been an object of fascination for his readers, which is not necessarily conducive to a proper appreciation of his body of literary works. But, to be perfectly frank, there was certainly enough dirt there to titillate the imagination. It is easy to imagine the first modern biographers of Prévost, from Henry Harrisse to Claire-Eliane Engel, and including Henri Roddier, discovering with astonishment the riveting existence of this ex-Benedictine monk apostate novelist, erudite church scholar, bon vivant, philanderer, occasional crook, apostle of the novel of sensitivity, and spokesman for the passions as well as for moral rectitude.

After schooling by the Jesuits, Antoine-François Prévost devoted eight years of rigorous studies to the Benedictines, then, in 1728, suddenly became famous with the publication of the first volumes of his novel Mémoires d’un homme de qualité (Memoirs of a Man of Quality, 1728–31). He began to rebel against the strictures of his monastic existence, requested a transfer to a more liberal order, grew impatient, then simply took French leave. Threatened with arrest by his superiors, he “tossed his habit into the nettles,” as he says, took refuge in Holland briefly, then crossed the channel into England. Soon dismissed from his job as a tutor in the home of an English gentleman, whom he apparently indisposed by seducing his daughter, Prévost returned to Holland in 1730 and settled down in The Hague. There he composed his famous Histoire du chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut (1731) and continued the writing of his monumental Le philosophe anglais ou Histoire de M. Cleveland (1731–39), begun in England, all the while courting financial ruin through his extravagant spending on his mistress Lenki Eckhart, a lady of ill repute referred to by one of Prévost’s contemporaries as a “bloodsucker.”

Leaving behind an insurmountable pile of debt, as well as a house full of furniture that the Dutch courts graciously sold for him, he crossed back over the channel in 1733, his beloved Lenki in tow, and took up residence again in England, where he began a weekly journal, Le Pour et Contre (The pros and cons), devoted to English culture and current events. Still in desperate financial straits, he was thrown into jail for cashing a counterfeit bill of exchange (i.e., passing a bad check) and just barely avoided an appointment with an Anglo-Saxon hangman before managing, at the beginning of 1734, to negotiate his return to France. Pope Clement XII having granted him an official pardon for all his sins, he was allowed to return to the Benedictines on condition that he do a second novitiate at La Croix-Saint-Leufroy near Evreux. He made peace with the Jesuits and published the first volume of Le doyen de Killerine (The Dean of Coleraine, 1735–40).

At the beginning of 1736 Prévost was back in Paris. Under the (rather slight) protection of the Prince of Conti, who appointed him his chaplain and gave him lodgings, the abbé quickly became the darling of the Parisian salons, who vied for his presence as much for his notoriety as an unfrocked and somewhat licentious Benedictine as for his fine wit and a vast personal culture acquired during long years of highly varied erudition, historical research for his novels, and popular journalism. He still benefited from the enormous prestige that he had gained with the success of the Mémoires d’un homme de qualité, Manon Lescaut, and the first volumes of Cleveland. His journal Le Pour et Contre, henceforth adapted to the French context, was still doing very well. Everything would indicate that Prévost’s personal and professional lives were, finally, beginning to look up.

The “Crisis of 1740” and the Genesis of The Greek Girl’s Story

Unfortunately, this was not the case. Despite the publication of the last volumes of Cleveland (1738–39) and the first two volumes of the Doyen (1739), Prévost still received no income from the church and was forced to put aside Le Pour et Contre for eight months. At the end of 1739 he was flirting with bankruptcy again. Thanks to Harrisse (Abbé Prévost, 299–302), the facts have become well known: because he was unable to pay fifty louis of debts, Prévost was threatened with arrest by a group of creditors led by his tailors and upholsterers. On January 15, 1740, he wrote a desperate letter to Voltaire in which he offered to write a “Defense of M. de Voltaire and of His Works” in exchange for the fifty louis he needed so badly; the illustrious philosopher politely declined the proposal. The debts continued to pile up, reaching “four or five thousand francs” at the end of the year. Prévost, his back to the wall, compromised himself in a shameful venture into scurrilous journalism and was forced once again to go into exile in January 1741, first to Brussels, then to Frankfort, before he was finally able to show his face again in Paris in September 1742 (Weil, “Abbé Prévost”).

Squarely in the throes of the 1740 crisis, in the second half of September, Prévost’s second literary masterpiece came out: Histoire d’une Grecque moderne (The Greek Girl’s Story). But this novel was buried, so to speak, in an intense literary production that also included, the same year, the publication of the last three volumes of Le doyen de Killerine, the two volumes of the Histoire de Marguerite d’Anjou, and volumes 19 and 20 of Le Pour et Contre, as well as the writing of the Campagnes philosophiques (1741), the Histoire de la jeunesse du commandeur de . . . (1741), and the Histoire de Guillaume le Conquérant (1742). That is a remarkable amount of writing, and it is difficult to avoid seeing a link between this frantic literary activity and Prévost’s financial dilemma—which led André Billy, a trifle cavalierly, to characterize all of the production of this period as “alimentary literature” (Un singulier bénédictin, 233)!

There has been no lack of reflection over the causes of the ruinous expenditures of Prévost, who seems to have squandered a fortune to put himself in such a fix. According to a suggestion from Roddier (Abbé Prévost, 43–44), based on comments by the chevalier de Ravanne (J. Gautier de Faget de Malines), the abbé’s former secretary in The Hague, Prévost picked up again in Paris with Lenki; it was for her, under the name of Mme de Chester, that Prévost courted financial ruin a second time, before she finally disappeared from his life upon marrying a certain M. Dumas in 1741. If we are interested in Prévost’s personal woes during this period, it is because one is tempted to see a connection, as do Jean Sgard and Robert Mauzi, between the sentimental tribulations of the abbé with Lenki–Mme de Chester and those of the narrator-hero of The Greek Girl’s Story. Prévost and his hero, in this perspective, were both “exhausted and aged” by the “miserable end of a long affair” and “in the portrait of the solitary old man, impotent, fallen, one can read a strange and ironic judgment by Prévost on himself” (Sgard, Prévost romancier, 406, 483). The Greek Girl’s Story would thus be, in Mauzi’s view, the transposition of the “suffering from passion” that Prévost experienced personally (Prévost, Histoire d’une Grecque moderne, ix). These are, of course, only hypotheses, however seductive they may be.

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.