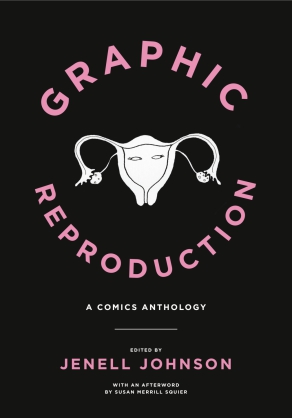

Graphic Reproduction

A Comics Anthology

Edited by Jenell Johnson, Afterword by Susan Merrill Squier

Graphic Reproduction

A Comics Anthology

Edited by Jenell Johnson, Afterword by Susan Merrill Squier

“Essential for anyone concerned with reproductive health care, this collection will also supply much-needed perspective to parents and would-be parents.”

- Media

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

The comics here expose the contradictions, complexities, and confluences around diverse individual experiences of the entire reproductive process, from trying to conceive to child loss and childbirth. Jenell Johnson’s introduction situates comics about reproduction within the growing field of graphic medicine and reveals how they provide a discursive forum in which concepts can be explored and presented as uncertainties rather than as part of a prescribed or expected narrative. Through comics such as Lyn Chevley’s groundbreaking “Abortion Eve,” Bethany Doane’s “Pushing Back: A Home Birth Story,” Leah Hayes’s “Not Funny Ha-Ha,” and “Losing Thomas & Ella: A Father’s Story,” by Marcus B. Weaver-Hightower, the collection explores a myriad of reproductive experiences and perspectives. The result is a provocative, multifaceted portrait of one of the most basic and complicated of all human experiences, one that can be hilarious and heartbreaking.

Featuring work by well-known comics artists as well as exciting new voices, this incisive collection is an important and timely resource for understanding how reproduction intersects with sociocultural issues. The afterword and a section of discussion exercises and questions make it a perfect teaching tool.

“Essential for anyone concerned with reproductive health care, this collection will also supply much-needed perspective to parents and would-be parents.”

“The stories are heartfelt, relevant, and entertaining. The art is warm and engaging. Altogether, it’s both an important teaching tool and a study in empathy.”

“As Graphic Reproduction spells out in black and white: the human reproductive experience gives life to the gray. It’s personal and political, hilarious and heartbreaking, joyful and painful, and everything in between. Forget the shoulds. It’s complicated, and that’s okay. This is what reproduction looks like.”

“This collection of comic narratives gives voice to non-normative, marginalized, and, in some cases, stigmatized stories in the arena of human reproduction. By sharing these rich stories, assumptions are challenged, biases are exposed, and stigma is lifted. These are stories of resistance to silence, norms, and expectations. These are stories that return voice, and the collection is an important contribution to Graphic Medicine.”

“Using textual and visual means, Graphic Reproduction not only documents reproduction in new ways but also forwards new conceptualizations of the range of activities, behaviors, and experiences within the idea of ‘reproduction.’ This is a rich contribution to the areas of the humanities, health and medicine, and reproduction.”

“Graphic Reproduction’s compelling and often heartrending comics cover aspects of reproduction—including infertility, abortion and miscarriage, labor, and postpartum depression—that are often excluded from popular discourse. Jenell Johnson’s careful, lyrical, and thorough introduction offers a resource for instructors beyond the excellent discussion questions that conclude the manuscript. Comics are well suited to depicting pregnancy for many reasons, but most enticing is the fact that, as Johnson notes, they allow us to imagine and visualize more hopeful reproductive futures.”

“A pedagogically practical, intellectually rigorous, and aesthetically pleasing volume with well-thought-out selections from the literature.”

“Comics tell the stories of artists and elicit emotions in the readers that would not have been made possible by solely words. In subject matter so sensitive and sometimes polarizing, the collection allows a safe space in which to become immersed in the human reproductive experience.”

Jenell Johnson is Mellon-Morgridge Professor of the Humanities and Associate Professor of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She is the author of American Lobotomy: A Rhetorical History.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction (Jenell Johnson)

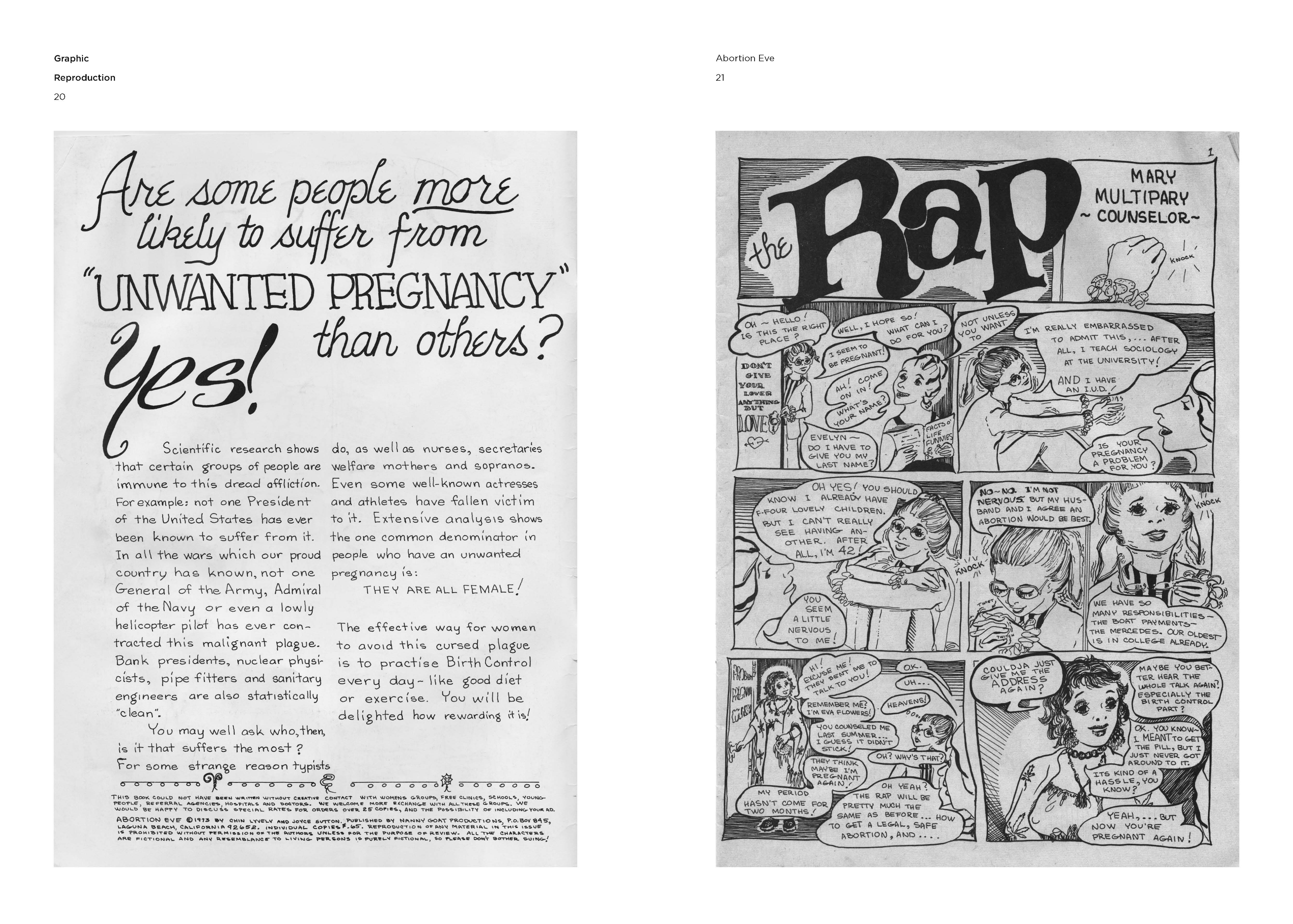

1. Abortion Eve (Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli)

2. Excerpt from Not Funny Ha-Ha (Leah Hayes)

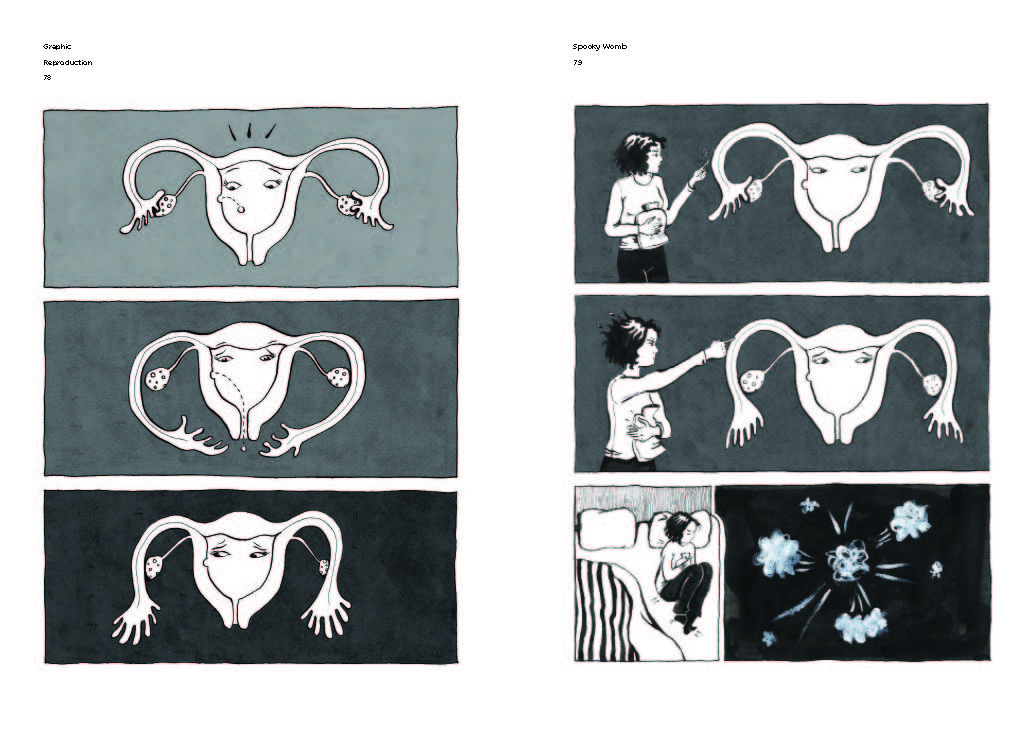

3. Excerpts from Spooky Womb and X Utero (Paula Knight)

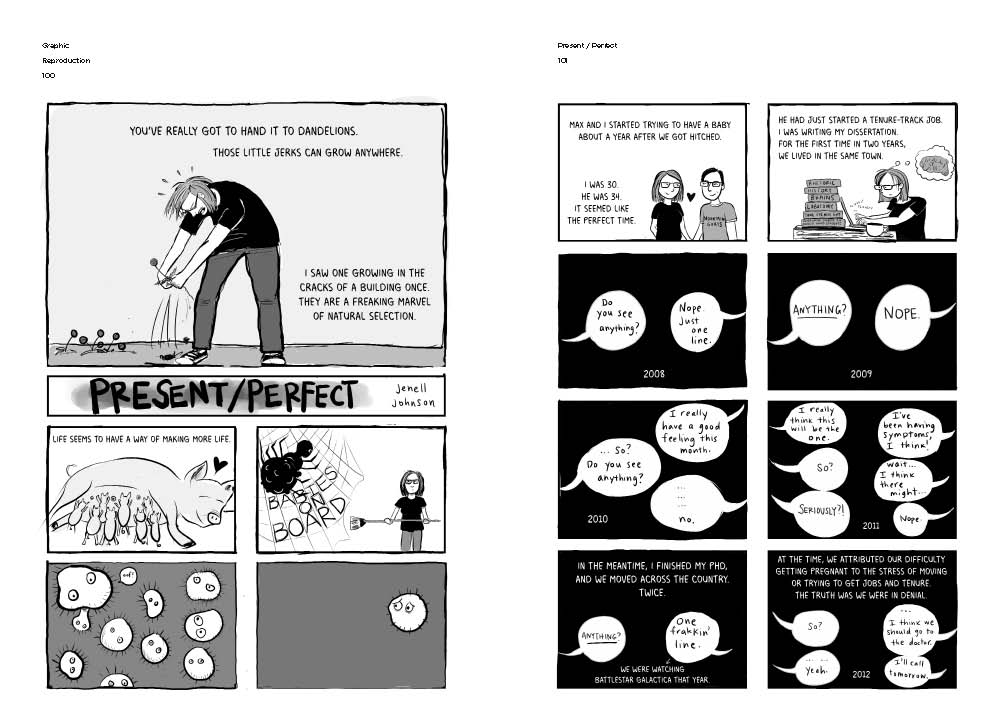

4. Present / Perfect (Jenell Johnson)

5. A Significant Loss: The Story of My Miscarriage (Endrené Shepherd)

6. “Losing Thomas and Ella: A Father’s Story” (Marcus B. Weaver-Hightower)

7. Excerpt from Pregnant Butch: Nine Long Months Spent in Drag (A. K. Summers)

8. Excerpt from Pushing Back: A Home Birth Story (Bethany Doane)

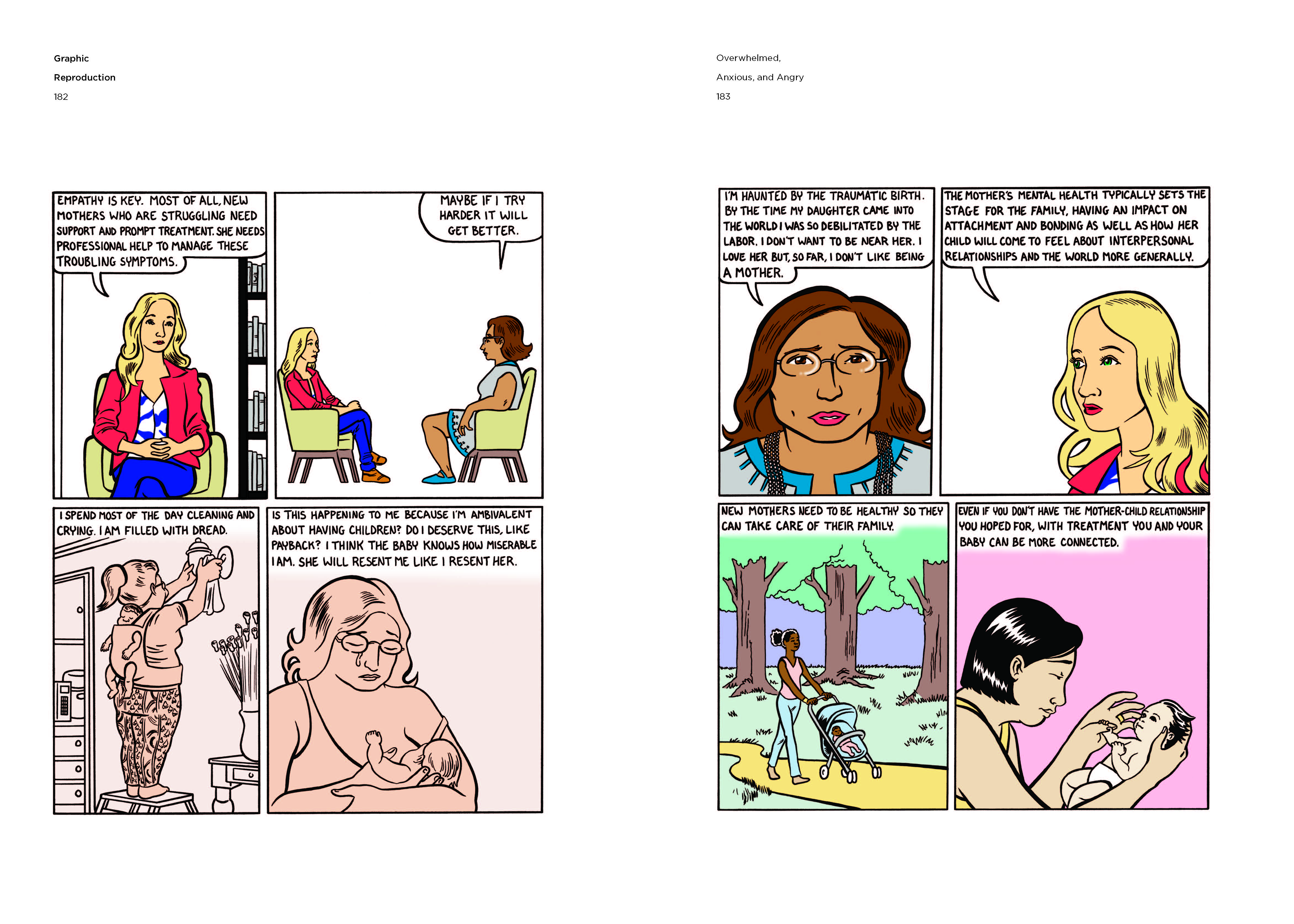

9. Overwhelmed, Anxious, and Angry: Navigating Postpartum Depression (Ryan Alexander-Tanner and Jessica Zucker)

10. “Anatomy of a New Mom” (Carol Tyler)

11. Excerpt from Spawn of Dykes to Watch Out For (Alison Bechdel)

Afterword (Susan Merrill Squier)

Classroom Exercises (KC Councilor and Jenell Johnson)

List of Contributors

From the Introduction

Jenell Johnson

There is a common story about human reproduction that circulates in Western culture. Two (middle- to upper-class, white) people meet, they fall in love, they get married, they have (heterosexual) sex, and then, after a glowing nine months of pregnancy full of ice cream and pickles, a (cisgender) woman has a (healthy, typical-bodied, full-term) baby, maybe two. Maybe two and a half. You know the rest: picket fence, bliss, happy endings, school, college, wedding, grandkids on a porch somewhere, everybody drinking lemonade in glasses tinkling with ice.

To call this narrative a “myth” is an understatement, of course, not only because it’s reproduced in nearly every form of media one can imagine, but also because few people have this type of experience with conception, pregnancy, birth, and raising children. A lesbian couple uses donor sperm and conceives via intrauterine insemination. A father spends the first few months of his son’s life in the neonatal intensive care unit, anxiously monitoring the vital signs of a tiny human who beeps instead of coos. A single woman gives birth to a baby who dies shortly after birth. A heterosexual couple enters the chutes and ladders of fertility treatment, only to find their way to a dead end. After an uneventful first trimester, a pregnant woman experiences a bad bleed in her second and spends the rest of her pregnancy on bed rest. A gay couple uses in vitro fertilization and a gestational surrogate, who gives birth to twins. A woman spends the first months of her daughter’s life in a deep depression. These experiences and many others are not aleatory events that somehow prove the rule of “normal” conception, pregnancy, and birth. Nor do they mark the ways that experiences of conception, pregnancy, and birth are changing in response to social, cultural, medical, and technological changes. They are simply examples of how varied and complex the experience of human reproduction is and has always been. Human reproduction is at once an utterly singular experience and utterly banal: after all, it’s happened billions and billions of times.

In humanities books about this subject, this is the point where authors position themselves in the text, drawing on decades of feminist arguments about the role of the personal and private in political and public life and offering a powerful illustration of these arguments. So this is the point where I must note that I do not have any children. And yet while I do not have children, I have quite a bit of experience with reproduction—or at least the attempt at it. I tried to get pregnant for seven years before finally calling it quits, and I went through just about every possible route to get there.

At some point during this multiyear process, I started keeping an illustrated journal about my experiences, which eventually became the comic Present / Perfect. I’m not sure why I started drawing comics about my failed attempts to reproduce, but as I’ve been working on this book, I discovered why I kept drawing them. To put it bluntly: I’ve never felt more like a body than I did while undergoing fertility treatment. Constantly monitoring and dutifully reporting my bodily processes day after day, month after month, year after year; getting injected, swabbed, poked, prodded, and measured both quantitatively (“this follicle is 3.5”) and qualitatively (“your lining is beautiful!”); undergoing invasive procedures and regularly looking at and thinking about my insides (usually with a group of people in the room): when trying to conceive, I was a (female) body first, and, most important, I was a body that didn’t work the way I “should.” After returning from yet another visit to the gynecologist, reproductive endocrinologist, or obstetrician, there was something thrilling about taking the instruments of representation into my own hands. In the pluripotent space of the comic panel, I had the power to represent not only my body and my experiences, but also my doctors, nurses, friends, and husband. Confronted daily by a pronatalist world that reminded me how abnormal I was, in the constant din of infertility testing and treatment—and then during my pregnancy and the grief that followed its loss—my pencils, pens, paints, and paper offered a quiet place to work out what was happening to me with some measure of critical distance.

French surgeon René Leriche once described health as life lived “in the silence of the organs.” Yet as Michel Foucault famously explains in Birth of the Clinic, medicine is not just an aural art but a visual one, and the two arts are intimately intertwined. The doctor’s silent observation is transubstantiated as speech; clinical observation, Foucault writes, “has the paradoxical ability to hear a language as soon as it perceives a spectacle.” Moreover, the “[precarious] balance between speech and spectacle” underlying medical practice and the scientific impulse to carry this balance forward to create knowledge about the body demand that speech and sight be translated into images.

Medicine makes pictures. Physicians look at and in their patients and craft maps of the body and its processes with X-rays, MRIs, CT scans, ultrasounds, and colonoscopy videos. These pictures, writes Ian Williams, “help construct the illness stereotypes that influence the way in which a condition is viewed by others as well as the patient’s experience of the condition.” Medical maps of the body, in other words, not only bring the body’s territory into being for scientists and doctors; they also represent cultural geographies that shape understanding of our bodies and our very selves. If the twenty-first-century self, as Nikolas Rose has argued, is anchored by a sense of somatic individuality—that is, an under- standing of the embodied self filtered through the lens of biomedicine—then this self is given shape through words and images. In the intensely visual domain of contemporary medicine, then, to experience health is to enjoy both the privilege of silent organs and the luxury of their invisibility.

The noisy presence of trauma, illness, and pain closely maps onto the experience of even the most typical pregnancy and birth. Many pregnant people (especially pregnant trans people and gender nonconforming folks) feel as though they are on constant display. To be an extraordinary body in the world is to be seen as available for public consumption. As Rosemarie Garland-Thomson writes, “because we come to expect one another to have certain kinds of bodies and behaviors, stares flare up when we glimpse people who look or act in ways that contradict our assumptions by interrupting complacent visual business-as- usual.” Staring is “an interrogative gesture that asks what’s going on and demands the story,” Garland-Thomson explains. “The eyes hang on, working to recognize what seems illegible, order what seems unruly, know what seems strange.” This initial interrogatory gesture of staring becomes folded into narrative, which may then be “carried over into engagement,” sometimes welcome and sometimes not. As many visibly pregnant people report, the engagement initiated by a look often turns into deeply personal questions and sometimes even direct touch.

As Anne Balsamo writes, “A pregnant woman is divested of ownership of her body, as if to reassert in some primitive way her functional service to the species—she ceases to be an individual, defined through recourse to rights of privacy, and becomes a biological spectacle.” The pregnant body in the world is first and foremost apprehended as a symbol: a narrative to be deciphered and an image to be seen, consumed, interpreted, and scrutinized. To be visibly pregnant, then, is to lose the privilege of privacy. Even further, visibility, as Peggy Phelan argues, “summons surveillance and the law.” A visibly pregnant body not only calls forth stares, advice, and touches, but also judgment, discipline, and control.

Like any other instantiation of power, the regulation of reproduction and the surveillance of pregnant bodies are not distributed equally. The history of reproductive rights in the United States and its territories, for example, is rife with examples in which calls for the individual right to birth control have been transformed into racist practices and eugenic policies of population control. Black, Chicana, Puerto Rican, Indigenous, disabled, and poor women have all been disproportionately subjected to institutionalized fertility control, including involuntary sterilization. As activists and critics have been arguing for generations, human reproduction is a place where the boundaries between biological, social, technological, and political life collapse, even while, as Emily Martin has argued, reproduction is also a site where discourse about the “natural” reigns supreme. Reproduction is a complicated process of meiosis, if you will—a merging of personal and political, body and ideology, individual and institution, science and technology, joy and pain, nature and culture, sex and gender, humor and horror, seeing and saying.

In this deeply tangled site, Graphic Reproduction seeks to intervene. Importantly, we do not aim in this book to unravel the many ways of under- standing reproduction; instead, we investigate their crossings and pull gently on their knots. In other words, this book does not seek to resolve the tension that arises among the stories in the following pages. What reproduction means for one artist is not what it means for another. There are (re)productive contradictions and rhetorical contractions throughout the words and images in this volume. The primary function of Graphic Reproduction is to provide a discursive and visual forum where the affective, biological, social, and political complexities of reproduction can exist together in generative uncertainty. The comics in this book offer a rich, multivalent perspective on human reproduction. In the rest of this introduction, I first situate comics about reproduction within the growing field of graphic medicine, with the requisite notes of caution about this positioning. Then, I introduce each comic included here and offer a brief reading of the work to illustrate some of the generative tensions that are revealed.

Graphic Medicine

The field of graphic medicine combines the discourses of medicine with the medium of comics. Scholars and practitioners of graphic medicine explore how comics can effectively represent the many voices and bodies involved in any healthcare encounter, and they draw on this multiplicity in productive and unexpected ways. In a landmark essay in the British Medical Journal, Michael Green and Kimberly Myers argue that the multiple perspectives of graphic medicine can be used to train more effective and empathetic healthcare providers. “Visual under- standing is intuitive in ways that verbal understanding may not be,” they write; comics might assist doctors to communicate effectively with their patients, and graphic pathographies—autobiographical comics about illness—may also help “patients and their families better understand what to expect of a certain disease.” Moreover, for medical students and residents, particularly those actively working with patients, these deeply engaging personal accounts of illness and medical care are vivid reminders that “healing a patient involves more than treating a body.” In this way, graphic medicine may be viewed as a subset of medical humanities, which is often presented as a method of training more effective doctors and nurses. While I strongly believe that comics—and the humanities more generally—can and should serve an important function in medical education (and I deeply hope that this book is used that way), there is a risk in viewing comics about health and medicine as yet another instrument in a doctor’s iconic black case. As Susan Squier argues in Graphic Medicine Manifesto, as medical humanities has begun to take a new shape as “health humanities,” the field has “expanded from an implicit endorsement of the practitioner’s emphasis on medical treatment to a critical incorporation of the caregiver’s or patient’s experiences, including the social determinants of health and wellbeing.” This perspective—the patient’s view, the view from below, the view from the table, as it were—is where the medium of comics comes to matter a great deal.

As the authors of Graphic Medicine Manifesto explain, graphic medicine is “a movement for change that challenges the dominant methods of scholarship in healthcare, offering a more inclusive perspective of medicine, illness, disability, caregiving, and being cared for. . . . [It] arises out of a discomfort with supposed techno-medical progress, working to include those who are not currently represented within its discourse.” Comics have long served as a medium to explore taboo subjects. Many of the earliest underground comics, for example, graphically depicted sex and drugs and pushed the legal envelope to the point where several artists, publishers, and comic shops were charged with obscenity. Although the underground comics movement of the 1960s and 1970s was largely dominated by straight white men, there were also many subversive women cartoonists, queer cartoonists, and cartoonists of color whose work was disseminated in political circles. As a medium already on the margins of “proper” literature and culture, then, comics offer an “ideal [forum] for exploring taboo or forbidden areas of illness and healthcare.”

(End of excerpt)

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.